Mark Chadwick can’t remember where he was when he heard that his band had officially become the biggest in the land, nor does he seem overly bothered about dredging up the memory. For the record, it was November 1995, and the Levellers – the folk-punk firebrands he had fronted since they formed in a Brighton pub at the fag-end of the 1980s – had notched up their first No.1 with their fourth album, Zeitgeist. It was an impressive feat, made doubly so by the fact that the gatekeepers of cool in the media had deemed the Levellers to be as fashionable as foot and mouth disease.

“What album was it again?” says Chadwick, squinting into the South London sun as we sit backstage at a late-autumn festival the band are due to headline later today. “Yeah, number one. That was great, I suppose. Where were we? Probably down the pub.”

He grins and shrugs with the diffidence of a man who genuinely doesn’t seem to give a fuck.

But then a large part of what the Levellers were built on was not giving a fuck. Or at least only giving a fuck about the things that truly matter.

Perched at the confluence of punk, folk and traveller culture, their left-leaning, rabble-rousing approach was a dog whistle to would-be radicals, impressionable students and anyone who dwelled outside the boundaries of popular music.

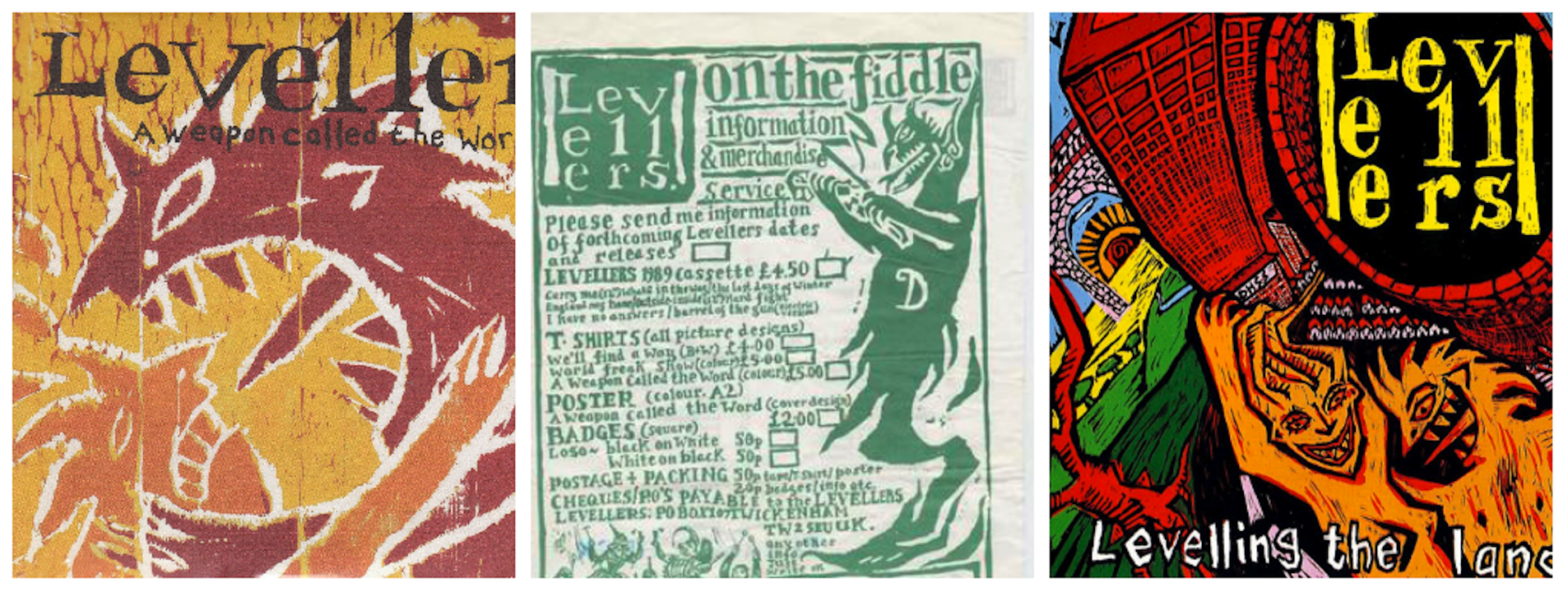

The surprise success of their second album, 1991’s Levelling The Land, and its libertarian call to arms, One Way, turned them into folk heroes in the truest sense – a band of the people with a travelling army behind them. The mainstream music press hated them with a passion that would do today’s Daily Mail proud, which proved that they were doing something right.

“When we started we were absolutely skint, living on the edges of society,” says bassist Jeremy Cunningham, a man with a rat’s nest of red dreadlocks tied up on top of his head. “We wanted to get our opinions across. The difference between people that had money and the people that didn’t made us angry. We wanted to change the world. Still do, really.”

To the undoubted annoyance of their critics, the Levellers are still here. They’ve kept the same core line-up since 1990 (Chadwick and Cunningham, plus guitarist Simon Friend, drummer Charlie Heather and violinist Jon Sevink, augmented since 2003 by keyboard player Matt Savage). They’re not unaware that their recent greatest hits album (featuring guest appearances from Imelda May, Billy Bragg and Frank Turner) and a forthcoming career-spanning documentary, A Curious Life, have nudged them dangerously close to the ‘heritage act’ bracket. “We’ve been going for twenty-six years,” Chadwick says wryly. “We must be classic rock by now.”

The days of Top 20 singles and headlining Glastonbury (they topped the bill in 1994, reputedly drawing the festival’s biggest ever crowd until the Rolling Stones’ appearance in 2013) are a thing of the past, but what they’ve lost in mass appeal they’ve made up for in self-sufficiency. The band own their own studio complex in Brighton, while their hugely successful Beautiful Days festival, set up as a reaction to the increasingly corporate mainstream circuit, is in its twelfth year, and pulling in acts as diverse as Ian Anderson, Primal Scream and Public Image Ltd

“The machine’s wheels are well oiled,” says Cunningham. “For all our reputation as anarchist, hippie types we run a pretty tight ship as far as stuff goes. It’s like a military operation.”

Even in a band of idealists, Cunningham stands out. As well being the bassist and co-songwriter, he’s also an artist who designs the band’s sleeves. He’s declared himself “an anarchist” in the past, though today he recalibrates that to “lunatic left socialist – we only called ourselves anarchists because we didn’t really trust anyone”.

He’s also the man who once shat in a box and sent it to the NME following a bad review of Levelling The Land, which didn’t really help the band’s relationship with the press. “They hated us already,” he says, punctuating his speech with a nervy laugh, which he does a lot. “I don’t think it did us any harm. We’ve always been seen as an outsider band, and it just did our rebel credibility more good.”

That rebel outlook had been nurtured in the pubs and squats of Brighton in the mid-to-late 1980s. The various members came from different musical backgrounds: Chadwick, an army brat, grew up listening to Led Zeppelin and Roy Harper; Cunningham was a dyed-in-the-wool fan of The Clash and Crass. Two things united them all: punk rock and anti-establishment sentiments. These were the days of the Thatcher government and the poll tax, of Socialist Worker and traveller culture – the final fling of Us versus Them.

It was the perfect time to be a band like the Levellers. Their first two albums – 1989’s A Weapon Called The Word and the breakthrough Levelling The Land – were as from-the-heart as you can get. Songs such as One Way, England My Home and the furious Battle Of The Beanfield crackled with revolutionary fervour. But elsewhere the likes of The Boatman and Carry Me possessed a we’re-all-in-this-together optimism, plugging directly into a lineage of British folk music. It helped take Levelling The Land into the Top 20, while the band found themselves at the centre of an entire subculture, pejoratively dubbed ‘crusty’. “We were right for a lot of people who were angry,” says Chadwick. “It chimed with what they were experiencing. There’s a lot of unity on that record.”

There was also an element of self-sabotage, which was largely Cunningham’s department. As if sending a turd to the music papers wasn’t enough, during an appearance on the Glastonbury main stage in 1992 the bassist called festival organiser Michael Eavis a “c**t” in front of tens of thousands of people. “People said that was cutting our own throats as far as a career goes,” he says. “But we never thought about a career. And anyway, he asked us back, didn’t he?”

It certainly didn’t harm them. Four of the five studio albums they released in the 1990s reached the UK Top 5, and 11 singles made it into the Top 40. Their mere existence was a form of protest in itself, but their songs were more than just clarion calls. On the likes of Hope Street, Julie and Just The One (the latter featuring Joe Strummer on piano), they didn’t just write about characters on the bottom of the pile, they empathised with them as well. Conversely, their most enduring single of the period, 1997’s uplifting Beautiful Day, coincided with the dawn of the New Labour era and captured the mood of the times. “We didn’t really think about it, but it came out at just the right time, with all that happening,” says Cunningham. “After about two weeks of us being all over Radio 1 and Top Of The Pops and all sorts of nonsense we hadn’t really done before, Princess Di had her car crash. Well, that was it for Beautiful Day.”

What they never were was cool – nor did they want to be. While their 90s peers were hobnobbing with politicians at No.10 or swinging with models at Supernova Heights, the Levellers were noticeable by their absence. The Britpop party was in full swing, but the Levellers had taken themselves off the guest list. “We did get invited to those things,” says Cunningham, “and we just said no.”

Of marginally more concern were the attentions of MI5. Back in 1990, at the time of the poll tax riots, a flyer for one of the band’s gigs at a squat in the anarchist’s warren of Peckham, South London had come into the possession of Her Majesty’s secret service. “They were, like: ‘Who are these Levellers characters?’” says Cunningham. “They followed us around for months, coming to gigs in plain clothes, sitting and watching while we were playing. They got Mark and sat him down for an interview. He was so drunk, he basically said: ‘Look, do I look like a threat to the civil being of the nation?’ I think after that they realised we were just a rock band.”

For all their rebel status, the Levellers haven’t always been immune to the clichés of rock’n’roll. During their heyday they spent thousands on hiring expensive studios. Chadwick recalls being locked in one such establishment for a month to come up with new songs. “I watched Mick Jagger, Eric Clapton and Pete Townshend come and go,” he says. “I wasn’t allowed to meet them. I was forced to sit there and write the next fucking Levellers album.”

As the albums got bigger, the band were living out their own Hammer Of The Gods fantasies. Of all the band members, Cunningham found success hardest to deal with. To cope, he cocooned himself away with a heroin habit. Inevitably, what began as an escape from a problem soon became the problem itself. In the documentary, he talks about having to remortage his house to pay for his habit.

“People would come up to you and say: ‘Your band is the only hope that there could be a change.’ And I’d be thinking: ‘If you really knew what I was up to you’d think I was a right c**t.’”

To their credit, they seem to have kept the ethical mistakes to a minimum. They’ve turned down headlining appearances at Reading (because they hated the festival) and support slots with Tom Petty and U2 (go figure). They knocked back countless requests to use their music in adverts, though the one instance they didn’t causes a collective wince.

“It was for Heinz, for some Weight Watchers thing,” says Cunningham, visibly embarrassed. “They took Beautiful Day. The roof on the studio needed fixing. It would have cost £40,000 and we were skint. This thing came in, so we gritted our teeth and took it. Absolutely heartbreaking.”

That moral dimension still informs everything the Levellers do. Today’s headline appearance is at a food-themed festival sponsored by one of the high street’s more middle-class food stores. When the band found out, they insisted on a charity donation to local food banks. Still, it’s the sort of thing that provides fuel for their critics. “We’re accused of being middle-class c**ts,” Chadwick spits. “Come on. We’re all fucking working class.”

It’s telling that the documentary focuses on the Levellers’ first 10 years. The slump, when it came, hit around the turn of the millennium – a combination of changing times and a stinker of an album in the shape of 2000’s Hello Pig. Since then they’ve pulled themselves up by their bootstraps and released a string of fine albums. Of course, there’s still the question of what they’ve still got to kick against.

“There are plenty of things for people to kick against,” says Cunningham. “It’s just more insidious these days. The gap between rich and poor makes me absolutely fucking angry. People’s apathy too. When we started out we had it drummed into us by all the anarchist punk bands: ‘You’re one voice, you can change stuff.’ We still are on the outside, I think. None of us ever fitted in, which is kind of why we became friends. We just didn’t realise we’d be outsiders forever.”