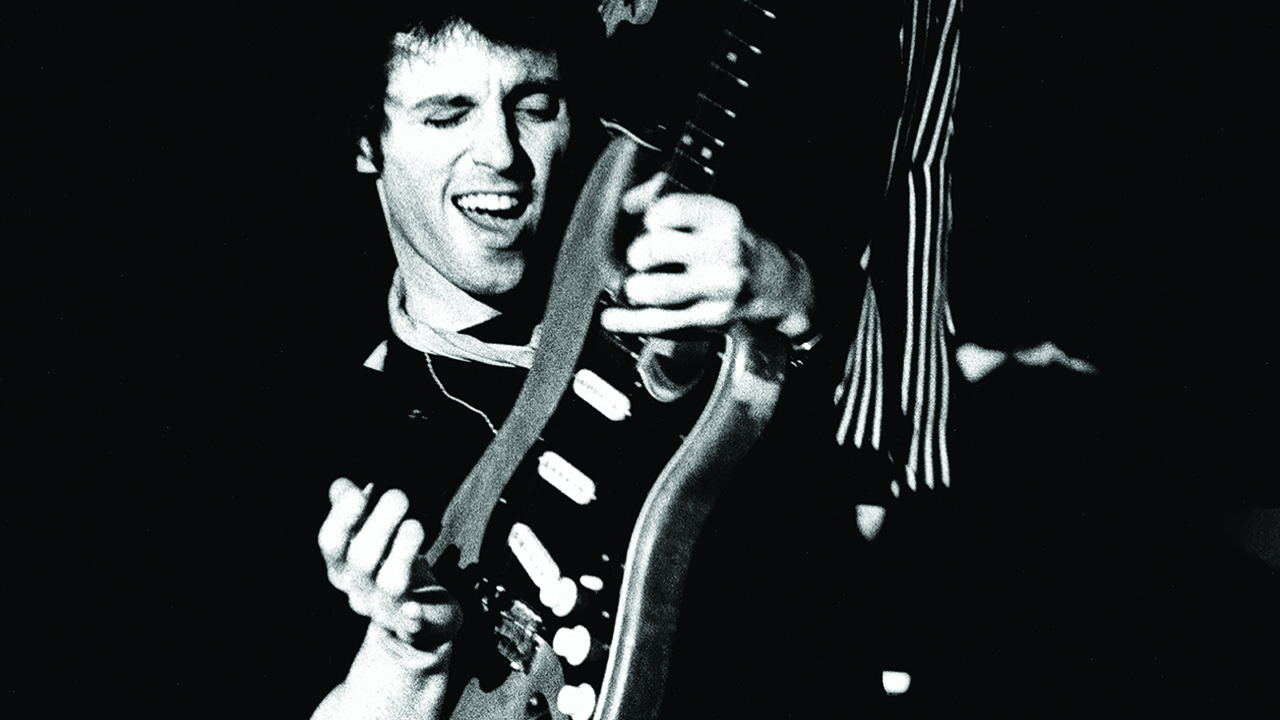

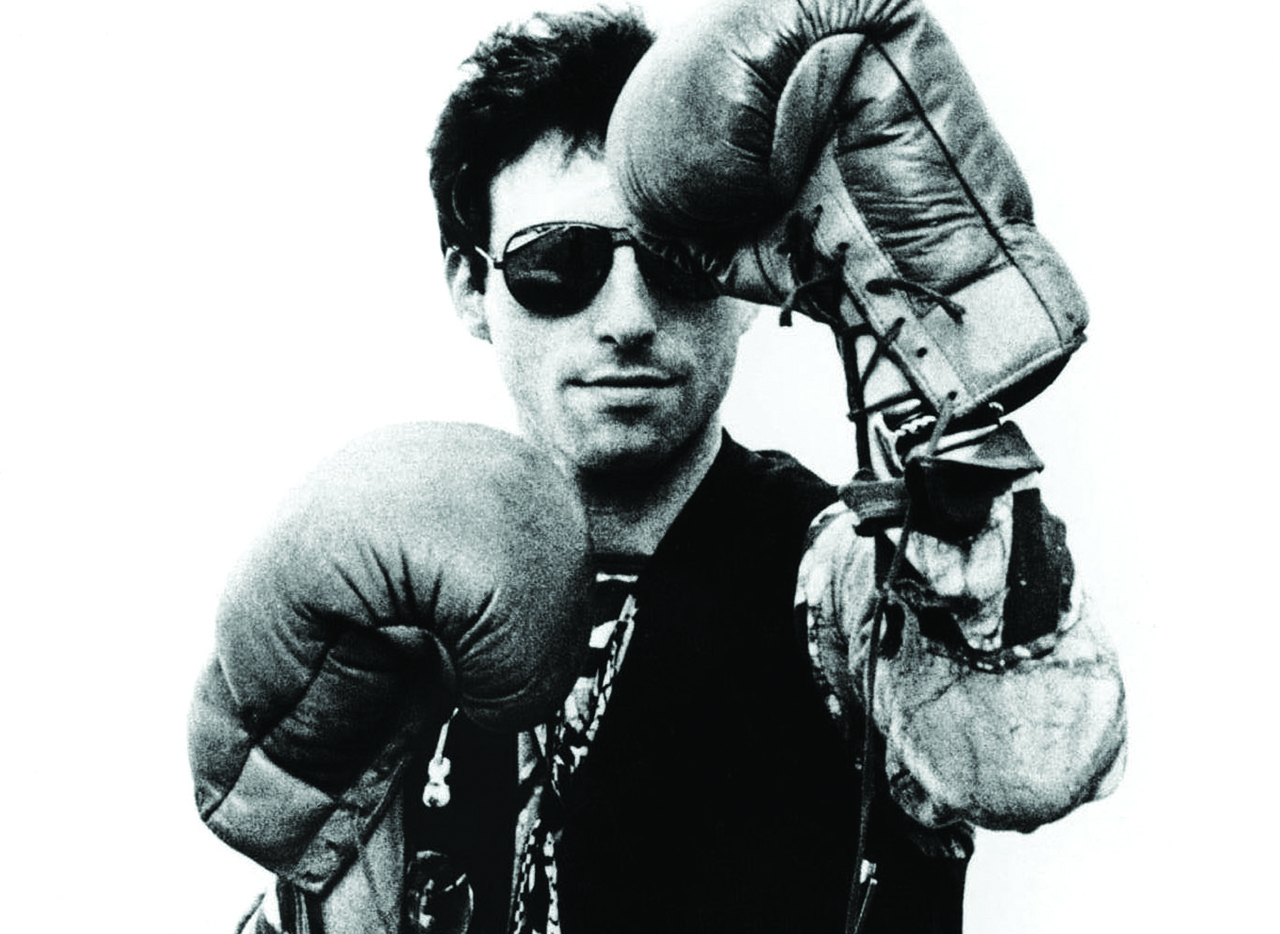

Nils Lofgren is the sort of musician they don’t really make anymore. An extravagantly gifted guitarist and otherwise jack of all trades, he’s been a loyal lieutenant and sideman to an assortment of rock’s maverick and genius figureheads in a career stretching back almost half a century.

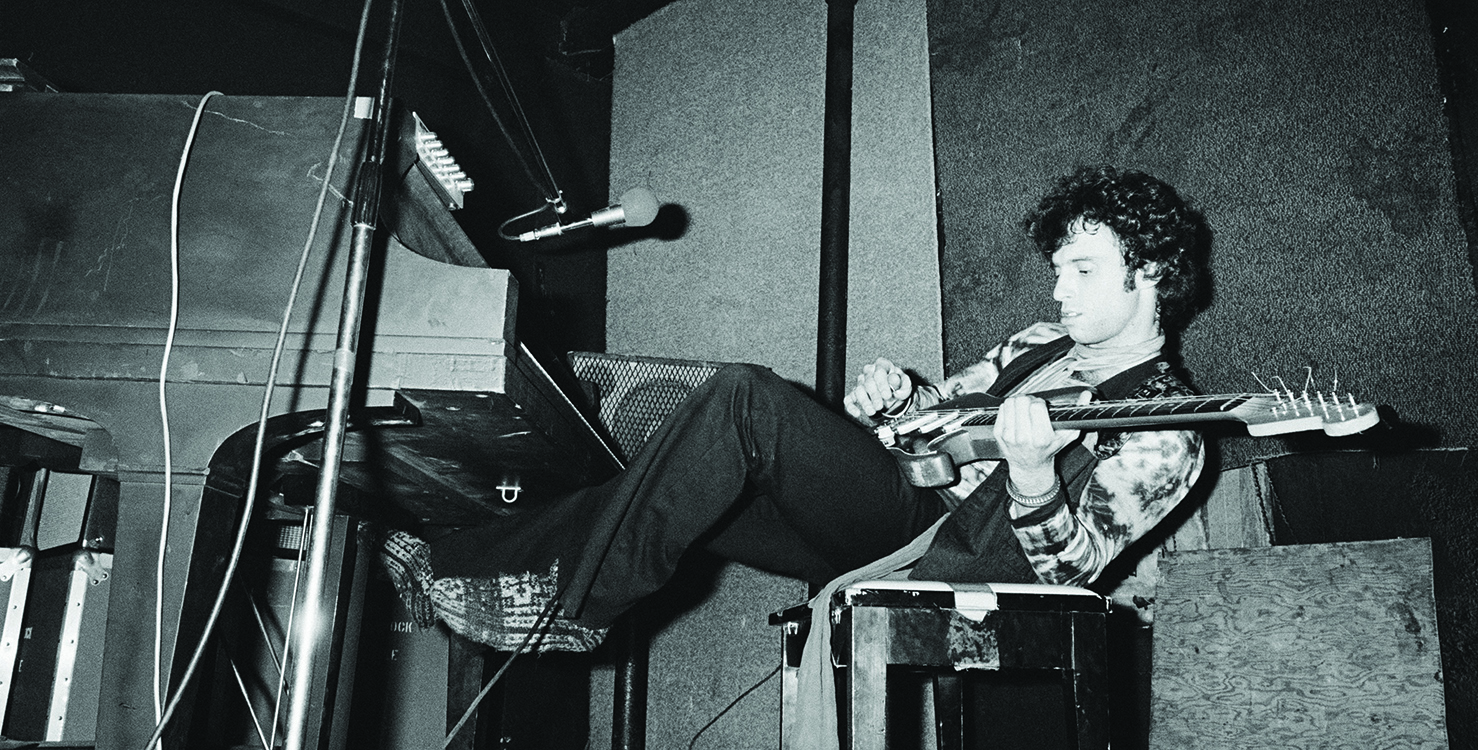

Born in Chicago in 1951 to an Italian mother and Swedish father, Lofgren latched onto music at an early age and never let go. By 1968, he had formed Grin, a proto-power trio built around his weighty riffs and for whom he was also singer and chief songwriter. Soon after this he met Neil Young, sneaking backstage at a local club to seek him out. As a wide-eyed 18-year-old, he added piano parts and his distinctive lilting vocals to Young’s watershed third album, 1970’s After The Gold Rush.

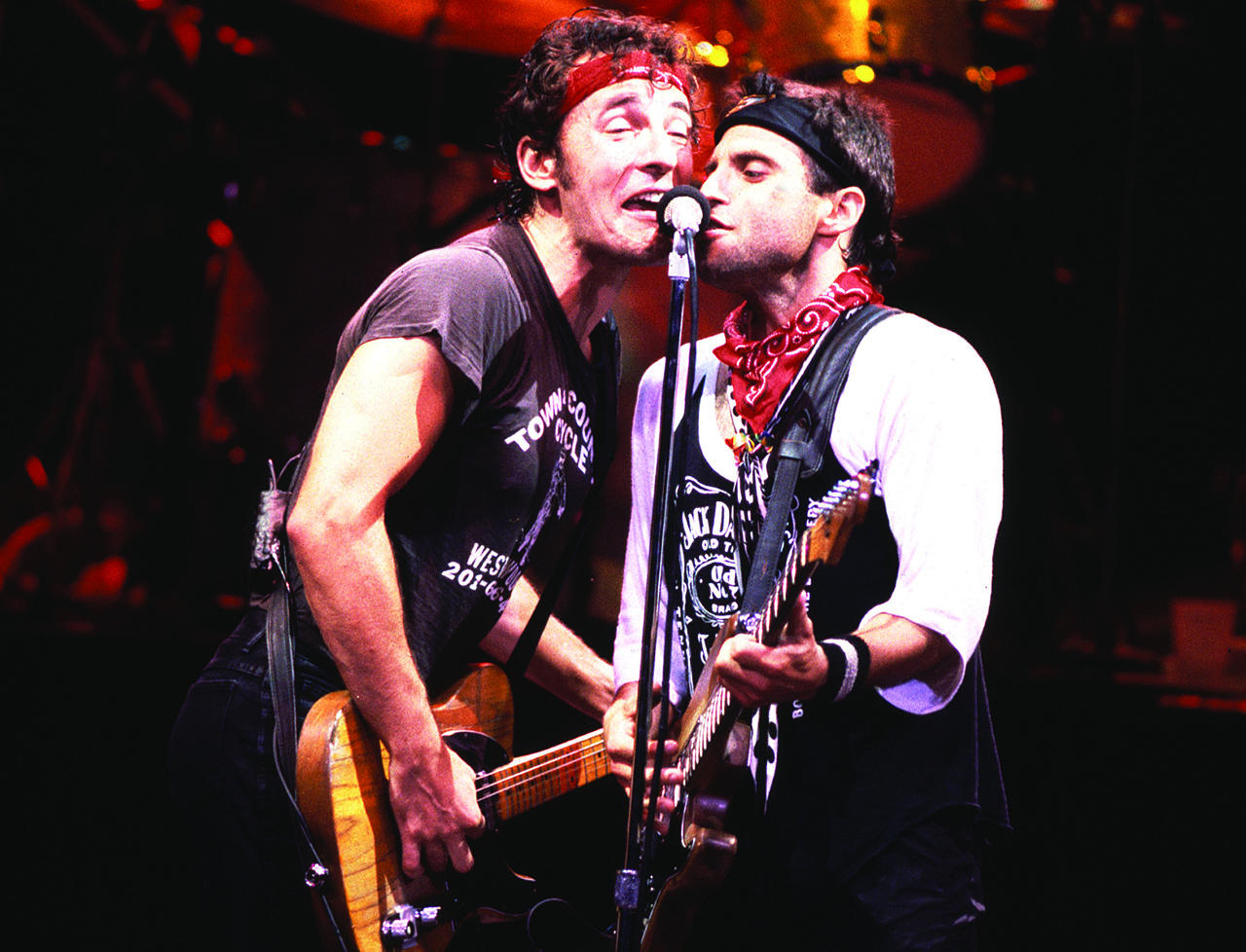

For the next six years Lofgren ran Grin parallel to his work with Young, making four albums with them that picked up positive reviews but sold poorly. By 1975, he’d split Grin and kicked off parallel careers as both a solo artist (he’s released 21 albums to date, most notably 1976’s Cry Tough) and trusty lieutenant to such heavyweights as Willie Nelson, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ringo Starr and, most visibly of all, Bruce Springsteen, signing up with the E Street Band for the globe-conquering Born In The USA tour and being a member of that stellar collective for 31 years and counting now.

A 2014 10-disc retrospective of Lofgren’s work with Grin and solo, titled Face The Music, contained glowing testimonials from such admirers as Joe Walsh and Elvis Costello, among others. His most recent recognition was, of course, the Outstanding Contribution award he picked up at the Classic Rock Awards. He refers to his acceptance speech, which ran for almost as long as that box-set, as “me blabbering on and on – I said none of the things I wanted to say and was way too serious,” adding with a chuckle: “My wife still wishes she had taken off a shoe and thrown it at me.”

On this particular morning in early December, Lofgren is at home in Arizona, having just returned from a 33-date tour of the UK and Ireland. He was up at the crack of dawn to walk his four dogs, and is contemplating spending the afternoon holed up in his music room, working on songs for his next record. That room is furnished with vintage guitars, an accordion and an upright piano, the tools of his craft and the means by which he continues to travel his long and winding road.

Can you recall the piece of music that first fired your interest?

If we’re talking about rock’n’roll, then, of course, it would be The Beatles’ I Want To Hold Your Hand. That led on to the Stones, the British invasion bands and then their American counterparts. There was also Motown, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Little Richard. But way back, from when I was five, my folks went out dancing and they played music in the home; it could have been_ In The Mood_ by Glenn Miller or any one of those classic American songbook swing band things that got me interested. Music was my refuge. Play Jumpin’ Jack Flash or any of those great Beatles songs now and it still does the same thing to my spirit and emotional being as it did forty-five, fifty years ago.

Effectively, you began training as a musician from the age of five on the accordion. Is self-discipline a key trait of your personality?

Well, I have the capacity to be disciplined, but it’s not something I tend to do day in, day out. I can sit and watch three football games in a row on the TV and eat a gallon of ice-cream with toppings, too. It’s more the case that I fell in love with the study of music and from that early age, it became a great therapeutic release for me. But in Middle America in the mid-sixties nobody thought you could play guitar for a living. I was sixteen when I saw The Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience on the same night, and I was possessed with what was then a really uncomfortable notion, that I needed to try this as a career.

You made a point of getting yourself backstage and observing musicians hanging out?

Basically, I went to any and every show. I was very panicked by the fact I knew nothing. I would try and sneak backstage and ask for advice. Sometimes I would get it. Sometimes someone was too busy or security would put me out. I followed Jeff Beck’s Truth band all around on their first US tour. I remember they played a roller rink in Alexandria and Beck’s manager, Peter Grant, a massive bear of a man, had me by the scruff of the neck and was dragging me down a hallway to throw me out. Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood rescued me, pulling me into a dressing room.

I got to hang out in Muddy Waters’ dressing room at a club called the Cellar Door. I snuck into a corner and asked him if it was okay if I sat there and watched him and his band playing cards. He just kind of smiled, said, “Sure, kid,” and then forgot about me. I didn’t talk to him past that, but just to be in a room with him… It all imprinted on me what a musician needs to be onstage and off. Same place, the Cellar Door, I also met Neil Young and [Young’s producer] David Briggs who was my greatest mentor.

And you ended up following Neil Young back out to California?

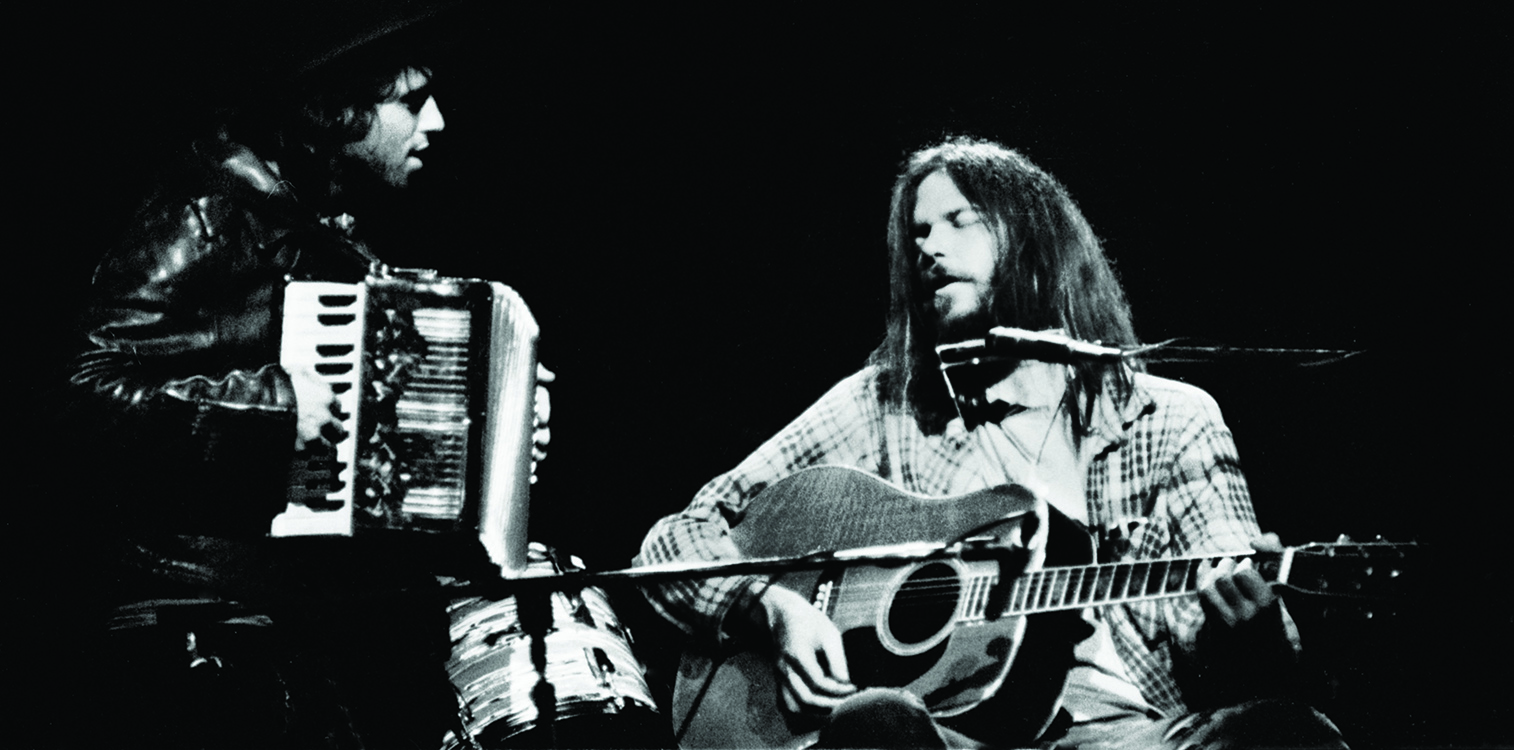

Grin had become a big local band in DC and we did some auditions for labels in New York but struck out, so we had decided to go to LA. Three weeks before we left was when I first befriended Neil and he had me hang out with him for a couple of days. I saw some shows and he had me sing some songs of mine for him that he liked. He said that when I got to LA, I should look him up. I did and true to his word he tried to help us. I moved in with David in Topanga Canyon and we became the house band at a local bar, The Corral, and Neil would sit in with us and advise us.

Playing on After The Gold Rush at eighteen, could you possibly get a sense of how indelible the music you were making would go on to be?

You know, I didn’t. Up to then I’d never even played a professional piano part. Neil and David both thought because of my accordion years that I could come up with some simple parts. I wasn’t sure they were right, so I practised all the time in the studio, never took lunch breaks. I was so wrapped up in my own part that I wasn’t thinking about much else. I do still remember also thinking, though, how much fun it was to go and work with a team of musicians and not need to be the boss.

What were your first impressions of working with Neil?

They’re the same ones that I have to this day. He’s very passionate and intense, but with a lot of common sense and also a sense of humour. Before I started this last UK tour, I went out and played at his Bridge School Benefit gig in San Francisco. I hadn’t been back there in a long time, since the first two or three shows he did in fact. In addition to my own set, Neil had me come out and play piano with him and it was on the exact same piano I’d played on After the Gold Rush. It was very spooky, but spooky never felt so kind.

Making and touring Tonight’s The Night with him must have been a very different experience?

From my perspective, that was a wake album. We’d lost Danny Whitten and Bruce Berry [respectively Crazy Horse’s guitarist and Stephen Stills’ guitar tech, both of them killed by heroin overdoses in 1973]. It was a very dark, intense but healing adventure. Neil wanted to make a live record, extremely rough, to not even have the musicians know the songs too well, the antithesis of production. We recorded in this pretty funky little room in Hollywood. We’d get together at dinner time, shoot pool, sip some tequila, pretty much till midnight, talking about Danny and Bruce, commiserating, and then get round a table and Neil would start showing us these songs. He’d kind of map them out a little, but we wouldn’t practise them a whole lot. David impressed on us to stay down on the tracks at all times, because the second Neil got a vocal that he liked, we’d be done. No one could fix a single note.

Then we took it out on the road in England and were touring an album that no-one had even heard at that point. People were booing and yelling for the hits. Neil would be pounding the piano with the heel of his hands and I’d play guitar with my teeth. It was so stream of consciousness and the audiences didn’t know what the hell they were seeing. We’d open with Tonight’s The Night, same as on the album. Sometimes, if a crowd was especially rude or demanding, we’d come out for the encore and Neil would say, ‘Okay, folks, we’re going to play something you’ve heard before.’ The place would go mad, wondering if it was Cinnamon Girl or Down By The River, and we’d play Tonight’s The Night again instead and piss everyone off even more.

How did you navigate the shift from that to leading your own band?

Well, I’ve tried to encourage all of my bands to have musical freedom and to add their own bits, to surprise me. Being in a great band, of course there’s a band leader who sets the direction, but I’ve always managed to avoid any situation where that got oppressive. My first solo album, with David Briggs, there was kind of a reckless, free-form vibe. I was living in a little cabana out at Malibu, the porch on the sand and working in a little wooden room with one guitar and a piano in it. That was a very simple record to make, but then, every step of the way has been a magical ride.

Do you feel any bitterness at not having had a big hit record of your own?

Bitterness is not the correct word, no, but disappointment maybe. At the end of the day, though, I’d imagine if either Grin or myself had started having hits early on, I may never have wound up playing so much with Neil, Bruce and all of the other greats I’ve had the good fortune to work with.

And presumably you saw first-hand both the good and dehumanising effects of massive success on the Born In The USA tour?

I was buying tickets to see Bruce and the E Street Band at the Bottom Line in New York on their first tour, so I was blessed that he and the guys thought I could cut that gig when Stevie [Van Zandt] went off to make his own records. Bruce had up to then always said he would never leave the sports arenas because stadiums were not intimate enough for him. But the album got to be so big that there were literally hundreds of thousands of people who couldn’t get a ticket to see him. So Bruce reconsidered and the first couple of stadium shows were rocky and uncomfortable for him, but like the master showman he is, within half a dozen shows he was turning a stadium into a nightclub. Despite all of the challenges, it was fun being in that band as they made that transition.

You first met Ringo Starr in London on that tour, too, and went on to play with him for four years.

We went to his birthday party after a show at Wembley and there was a late-night jam session during which I got to visit Ringo. We had a long talk over a couple of drinks, he gave me his number and said stay in touch, which I did, and in 1989 he calls and tells me he’s putting a band together because he needs to go out and play. That band was Dr John and Billy Preston on piano, Clarence Clemons on sax, Levon Helm and Rick Danko from the Band, Jim Keltner on drums, and Joe Walsh and I. Look, you’d be hard pressed to tell me a band with more talent.

One night, I was up on the drum riser and we’re playing a song, and Ringo goes to me, ‘Man, I can’t believe how great this all sounds – I’m hearing everything.’ I told him he’d got these great monitors under his riser blowing a stereo mix up at him. He looked at me and said, ‘What’s a monitor?’ They didn’t have monitors when he’d last played with the Beatles. To watch him like that, like a kid in a candy store, really was a beautiful thing. He was one of the Beatles, man, but like he said, also a drummer and he needed to go and play.

Is there any one thing that connects the best that you’ve worked with?

In my opinion, it’s their ability to be a channel, to let their own gift, and whatever else’s out there, come pouring through without blocking it. That’s an inherent similarity between them all.

And what do you think has been the essence of your own forty-eight-years as a professional musician?

The song, really, is the core of everything, and as a musician I think I just have an innate ability to stay out of the way of the singer and the song he or she is singing. That has served me really well.

Nils Communication

The best of Lofgren, from Neil Young to Springsteen to Lou Reed.

Southern Man

Neil Young

The teenage Lofgren doles out basic, but colouring piano fills on this driving, signature song from Young’s classic third album.

From: After The Goldrush (Reprise, 1970)

White Lies

Grin

Lofgren-penned standout cut from his first band’s second album, a pop-rocker that opens out into a widescreen chorus – and a No.75 US ‘hit’.

From: 1+1 (Epic, 1972)

Keith Don’t Go

Nils Lofgren

Hearing rumours of Keith Richards’s imminent demise, Lofgren crafted this appropriately Stones-y epic for his solo debut.

From: _Nils Lofgren _(A&M, 1975)

Roll Another Number (For The Road)

Neil Young

Woozy, weary-sounding lament from Young’s meditation on death, with Lofgren providing honky-tonk piano fills.

From: Tonight’s The Night (Reprise, 1975)

Stupid Man

Lou Reed

Co-written with Lofgren. Lou comes across as sounding both urgent and uncharacteristically welcoming.

From: _The Bells _(Arista, 1979)

Secrets In The Street

Nils Lofgren

The solo smash hit that never was: a typically overblown 80s production, but underneath a yearning, blue-eyed pop-rock gem.

From: _Flip _(Columbia, 1985)

Seeds

Bruce Springsteen

Recorded at LA Coliseum on one of the last dates of the epic Born In The USA tour and giving rise to a ferocious Lofgren solo.

From: Live 1975-1985 (Columbia, 1986)

Silver Lining

Nils Lofgren

Back solo after Springsteen dissolved the E Street Band in 1989, Lofgren served up this hulking blues number.

From: Silver Lining(Rykodisc, 1991)

Youngstown

Bruce Springsteen

Brooding acoustic track from Springsteen’s Ghost Of Tom Joad album transformed into an electrical storm, Lofgren soloing like white lightning.

From:_ Live In New York City _(Columbia, 2001)

Radio Nowhere

Bruce Springsteen

Pulsating opener from the best of Springsteen’s latter-day albums and with Lofgren sitting back and driving the rhythm along.

From:_ Magic _(Columbia, 2007)