The only person who wasn’t surprised when Tom Petty died from cardiac arrest on October 2, 2017, was Tom Petty. Prescient always – blame it on being part Cherokee – but from as far back as 2006, death had entered the equation for the rangy guy from Florida.

On that Easter Monday in 2006, while reluctantly doing press for the just-about-to-be released Highway Companion, his third solo album, he talked about the future, or what he thought he had left of it. In his airy studio, located in a wing of his baronial homestead about a quarter of a mile above California’s Pacific Coast Highway, there was something chilling about talking about matters so dark and serious in a light-filled room tucked away under flowering wisteria and pepper trees.

“One of my great strengths as an artist when I was young was realising that I had the time to do everything – anything was possible, there was an infinite amount of time,” he said, perched a little precariously on a tall bar stool. “I didn’t sweat things as much. When people talk about those record-company battles and how courageous it was, it was because I knew I had the time to get out of [the deal].

“I wouldn’t want to get into the middle of something like that now. I’m more aware of a limited amount of time. I know baby boomers seem to think they should live longer than anyone: ‘Oh my God, we are the greatest people that ever lived!’ The truth is that I don’t know if I am gonna live that long, and I want to get as much done as I can, so now time is really precious to me.”

Only 55 at the time, he had a sense of urgency in him, a man aware of more road behind him than in front. I pointed out at the time that Ronnie Van Zant had told me something similar 30 years before, and we both knew how that turned out – especially since Lynyrd Skynryd’s plane crashed on Petty’s 27th birthday.

He gave me a funny look and then bent over my tape recorder and told me resolutely: “I want to go out quickly. I don’t want to lie around in a hospital and die slowly.” Leaning even closer to the recorder, he said, “Just for the record, I don’t want to die in a plane crash. Really don’t want to do that.”

We laughed a little about that, but the tone continued to be sombre on the early spring afternoon. “You know, you get concerned with what you leave behind. Artistically, the biggest priority with making records now is that I know this will be here longer than me. Making something that lasts is more important than it being a hit record – although you want them all to be hit records,” he laughed a little ruefully.

While he would never again make a solo album, Petty would go on to make just two more Heartbreakers records, Mojo in 2010 and Hypnotic Eye in 2014. He also found time to re-form Mudcrutch, the 1970 predecessor to the Heartbreakers that featured a 20-year-old Petty on bass, Tom Leadon and Mike Campbell on guitars, Randall Marsh on drums and Benmont Tench on keyboards. “I did it because I could,” he said drolly, when asked about it in 2016.

At the time, it didn’t seem like he was checking things off a bucket list, but looking back on it now, perhaps he was. He produced the recently released Biding Time for one of his early heroes, Byrds bassist Chris Hillman, and gave The Shelters, a band of 20-somethings who were friends with his adopted son Dylan, the run of his studio, and eventually produced their self-titled debut for Warner Bros last year. Then there was the matter of the 40th-anniversary tour, which started on April 20, 2017, and wound up five months later, although only a couple of years before he’d said he no longer wanted to do long tours.

“I know I don’t want to spend six months of the year going around playing shows, because there’s just not time to do that any more,” he’d said. “I don’t want to quit playing. But Benmont says if we don’t play to people it’s a crime. Maybe he’s right, but I don’t think we always need to play on tours. I think there are ways to go and play somewhere or film it.”

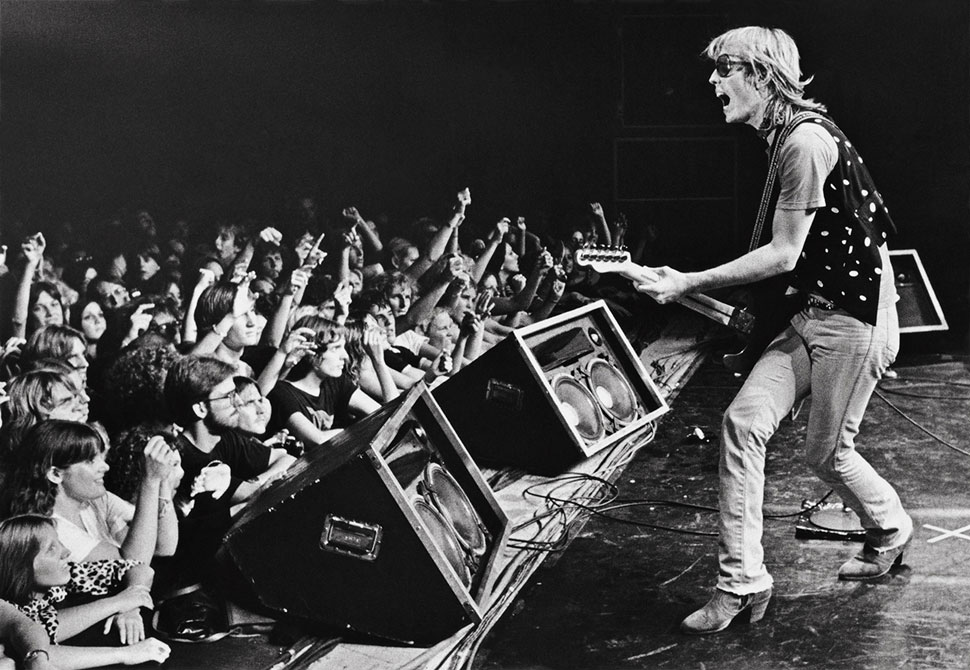

But he went ahead and did it anyway, mounting a full-scale stadium tour, bringing along openers from the Heartbreakers’ earliest days – Joe Walsh, Stevie Nicks, Peter Wolf – and young bucks Chris Stapleton and The Lumineers. Playing shows as if it were 1977 again, he ended the behemoth tour with a three-day stand at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, a week before he died.

Petty’s concern with making the most of his time extended to his songwriting as well. “Years ago I used to be so concerned that at least one of the songs was a single. I don’t think that pops up in my mind any more. But I know I don’t want to waste a line. I want everything to mean something, and I want it to be the right line.”

But despite all the talk about not caring about hits, Highway Companion would go on to top the Billboard chart, as would Hypnotic Eye in 2014, while Mojo hit No.1 on the Top Rock Albums chart.

If anything, throughout his career Petty was someone who underplayed his hand, despite the three Grammys, the 80 million records sold, or Buried Treasure, his top-rated radio show on Sirius XM. No braggadocio, ever, just the sense of certitude that anyone could do what he could do if they just applied some hard work. Like he had.

When he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall Of Fame in 2016, along with Nile Rodgers, Lionel Richie, Elvis Costello and Wild Thing composer Chip Taylor, he looked bemused, telling the audience, “I’m sort of the rock’n’roll white trash section of this show.”

While all the other recipients went on about how they wrote songs, why they wrote songs, peppering their stories with slightly inappropriate admissions and self-aggrandising jokes, Petty kept his speech at a lean two minutes, telling the audience that the world really doesn’t need any more songs.

“If no one ever wrote another song, we’d be fine, you know? There are plenty of songs. But I still do it, because I love it and it’s a gift. It’s not something everybody can do. Well, everybody can do it, but they can’t do it good.”

Which is as close as he’d come to admitting there was something extraordinary about what he did.

There was something endearing in Petty’s humility. He always took great pains to show his humanity, confiding that he couldn’t fall asleep without the TV on, that the only thing that could ever really calm him down was a walk along the Pacific Ocean, or that he really would love to fish again – all things that would soothe his forever‑restless spirit.

While seemingly affable, he was a little more complicated than that. For one, he didn’t suffer fools gladly. I once had the temerity to ask if his current album were a colour, what it would be. He narrowed his icy blue eyes and said more than a little impatiently. “I don’t think it’d be one. It’d be a whole bunch of colours. Each song is a different colour and different shades. There would be a lot of silver in it though.”

I should have left it there. I didn’t. “Because it’s sleek and it’s a vehicle?”

“Maybe. I don’t know. Now my bullshit meter is going really high,” he said flatly, a clear indicator that it was time to back off.

But to his great credit, he never claimed to be perfect. “What bugs me? Waiting on people drives me insane. I didn’t [just] write that song. I am very punctual,” he laughed.

He had very little sense of humour when, for example, people thought the key line of Into The Great Wide Open was ‘a rebel without shampoo’. “It’s nice if people get the songs,” he said. “But I hate being misunderstood. I hate it when people get things wrong. I’ve seen people get lyrics wrong and that drives me nuts. I’ve seen them read their own meanings into things that are such nonsense. I shouldn’t care about that, but I do.”

Excessive drinkers were also on his hit list. “I can’t stand drunks. I really have a distaste for people who are drunk. I don’t like drinking, which has probably not been the best thing in the world for me.”

Back in 2006, he said: “I can’t say I don’t take drugs. That’s really a good place to get to, and I’m trying to get there. I’ve been such a nut I wonder sometimes how long I’m gonna live. My kids call me the pirate. I’ve lived hard and gotten a lot out of life. I sure took an adult portion.”

Some might say it was self-medication. And he had every right to it, given his tumultuous childhood. “I haven’t had a life like other people have. I never felt safe as a child. I grew up in a redneck household and I always hated it,” he revealed in 2012. “If you’re in an abusive situation – my dad was very verbally abusive – you need a safe place. I took refuge in music. Rock’n’roll was my safe place.”

What he never could say to Earl Petty he funnelled into his songs, creating a world where if he didn’t feel safe, he certainly felt in control. I Won’t Back Down, Don’t Do Me Like That, Into The Great Wide Open and I Need To Know speak volumes about the necessity of living life on his own terms, even if he was inventing it along the way.

“You think I don’t know I’m a control freak?” he asked in 2012, raising a speculative eyebrow. “I admit it. I’m a ridiculous control freak.”

What do you need to control more than anything? “Myself,” he said. “The hardest thing to control is myself, and I’m working on that.”

Despite appearing to be one of the more balanced celebrities, there was something about Petty that was unknowable.

“Okay, I’m not really all that balanced,” he explained. “People see me as normal. I’m not, really. I think I’m very complicated. I mean, what does it say about me that I feel more comfortable onstage than I do off? Life is much more complicated than a rock’n’roll set.”

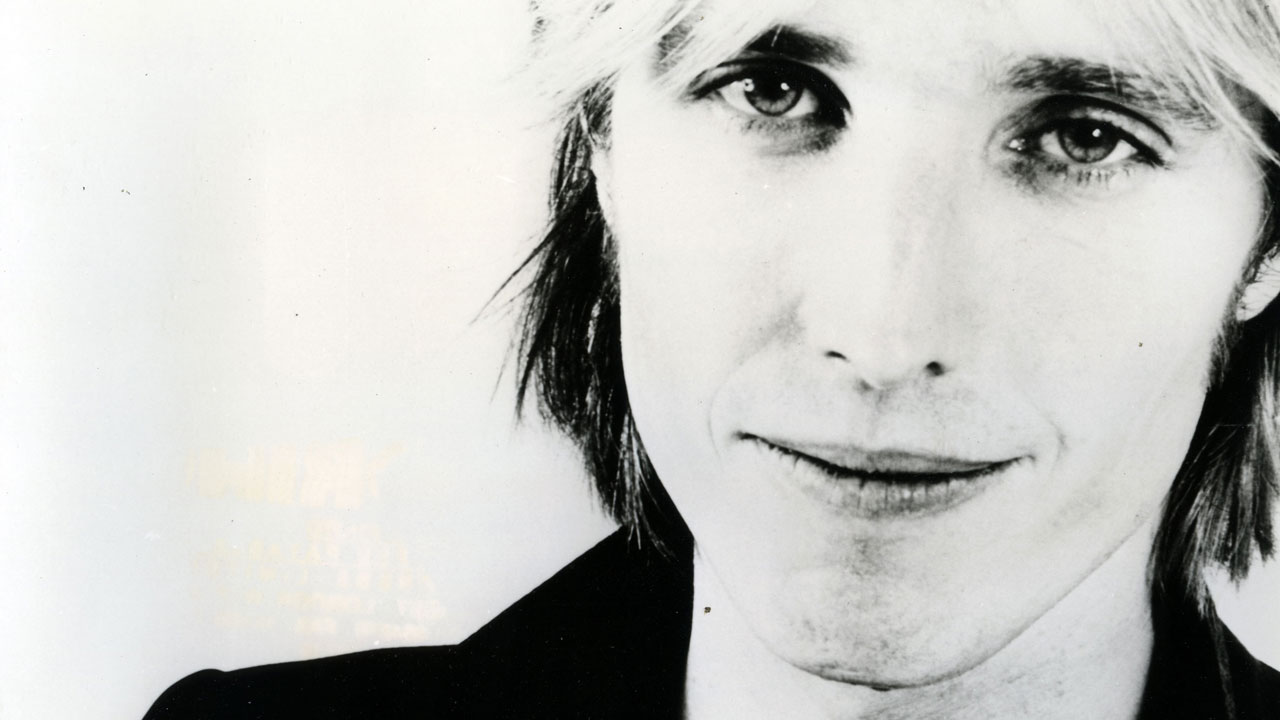

Even from the earliest photographs, you always had the sense that Petty thought he was getting away with something, daring you to call him out. You can see it in the photo on the cover of Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers, his 1976 debut album. The knowing half-smirk, half-sullen stare from his pale eyes, Dressed in a new black leather jacket, a string of bullets slung across one shoulder like Pancho Villa, a penumbra of smoke encasing his blond head, the Florida native was on a mission, and it was clear he had just got started.

Although that mission really started back in 1961, when at the age of 11, he met Elvis Presley on the set of Follow That Dream in Crystal River, Florida. That encounter set his pre-teen aspirations on fire (revisited in his own Running Down A Dream).

“To be truthful, I didn’t really meet Elvis, but I did stand really close to him,” he confessed later. “I had an uncle who was in the film business locally – he would shoot and develop film. My aunt asked me, ‘How would you like to go see Elvis Presley?’ I said, ‘Wow, Elvis Presley!’ but then I would have gone to see anyone famous who was a big deal.

“It was everything you thought it would be: this huge ordeal on the street, with hundreds of people and screaming girls and police holding them back. We were taken in the back where there were all these trailers, which now is very normal to me, but at the time it looked very strange. We just stood there, and this line of white Cadillacs pulled in. These guys were getting out. Most of them had those shiny mohair suits and pompadours.

"As each one got out I would ask my aunt, ‘Is that him?’ And she would say, ‘No that’s not him.’ Eventually he pulled up in his Cadillac and got out. I didn’t have to ask. There was no doubt about it. He was about the best-looking thing I’d ever seen. He walked up and my uncle said, ‘Hey, Elvis, this is my nephew and my niece.’ He looked at us and kind of smiled and nodded and went in his trailer. It was so, so cool.

“After that day I never thought about much else but rock’n’roll. It certainly changed my life.”

The next year, he convinced his mother to buy him his first guitar, and then on February 9, 1964, like countless other teenagers, he saw The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show and began making his own plans. “That was my way out. There was a way to do it,” he said to Paul Zollo in Conversations With Tom Petty.

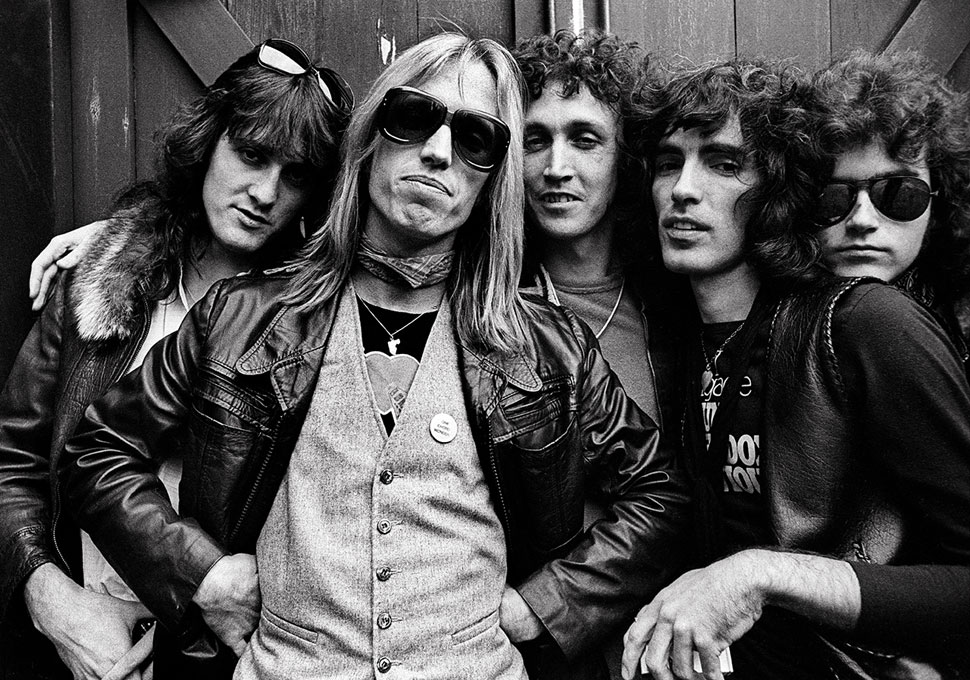

He did it in not-so-gradual stages, beginning his career in the Epics with high school friend Tom Leadon. With the inclusion of Mike Campbell, his roommate Randall Marsh and the three-years-younger Benmont Tench, they became Mudcrutch, a band Petty said were “The Beatles of Gainesville.”

But even that wasn’t enough. In 1974, Tom Leadon’s elder brother Bernie (Eagles, Flying Burrito Brothers) convinced them that the streets of LA were paved with recording contracts, so they sent out a scouting party to check out whether he was right.

Within days of arriving, Petty was pumping fistfuls of change into a pay phone at the corner of La Brea and Sunset in LA, cold-calling record companies from a list of phone numbers found propitiously on the floor of the phone booth. By the time they were ready to return to Gainesville, they had not one but two offers from labels, eventually resulting in their self-titled debut on Shelter Records and a gradual rise to the top echelon of American rock bands.

There was something uniquely real about Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers. They held up a fractured mirror for the rest of us, a mirror that actually reflected back some less-favourable angles. You believed that he actually suffered some of the same indignities and frustrations as everyone else, and had to think his way out of more than a few jams. He was one of the few rock stars who put his money where his mouth was.

When Shelter was sold to major label MCA Records in 1978, Petty contended that the sale violated his contract. That led to a whole year of legal wrangling, which ended up with him bearing all the costs of recording his next album himself, driving him to declare bankruptcy in May 1979. That case was resolved only when Shelter finally accepted a settlement and bowed out of the picture, and MCA allowed Petty to sign with subsidiary Backstreet Records, resulting in his breakthrough album, Damn The Torpedoes.

But MCA went back on a promise to release follow-up album Hard Promises for $8.98. Petty didn’t want to be the scapegoat for escalating record prices. He told the New York Times, “My beef with MCA was that they originally told us Hard Promises would be $8.98, and then changed their minds. But it would be wrong to single them out; every other record company would like to push record prices right up there. I’m not usually as concerned with record company business as you might think… but sometimes there’s a communications breakdown and when that happens you just have to stand up for yourself.”

That’s something he continued to do, whether taking the Red Hot Chili Peppers to task over commandeering Mary Jane’s Last Dance riffs for Dani California or polarising some of his fan base after he prevented George W. Bush from using I Won’t Back Down as a 2000 campaign song. But perhaps even more noteworthy is that Petty performed the song at Vice President Al Gore’s house in Washington, D.C., on December 13, 2000, an hour after Gore conceded the election to Bush. (I Won’t Back Down was performed as an anthem of solidarity on Saturday Night Live on October 7, 2017, by Jason Aldean, one of the performers at the Las Vegas country festival where 59 attendees were killed the day before Petty died.)

Over four decades, Petty released 13 albums with the Heartbreakers, along with three solo albums and two with the most super of supergroups, the Traveling Wilburys, whose line‑up comprised Petty, Bob Dylan, George Harrison, Roy Orbison and Jeff Lynne.

While many people would be daunted in the presence of a former Beatle, Petty had a rare knack to feel comfortable in any situation, and he ended up, to his own surprise, being the fulcrum of many important circles.

“I never want to meet anybody, but I always do,” Petty said in 2006 when asked about his friendship with Dylan and Harrison. “I have actually become quite close to them, but it wasn’t because I sought them out. They sought me out for some reason. My little coupling with Jeff Lynne and George was so cosmic.”

About a month after having dinner with Jeff Lynne in London, when the Heartbreakers were on tour backing up Bob Dylan, Petty pulled up to a red light and there was Lynne in the car next to him. Each was a little unnerved – neither knew the other was in Los Angeles – but they waved at each other, then drove away.

Petty didn’t think much about it until a week or two later when he and his eldest daughter, Adria, were out Christmas shopping and drove past a French restaurant they used to go to. Out of the blue, they decided to pull in, even though they weren’t sure the restaurant was still serving that late in the day. When they sat down, the waiter came up and told Petty there was a friend of his in the private dining room who’d like to see him.

Bemused, Petty followed the waiter, and there were George Harrison and Jeff Lynne.

“When I walked into the room, George said to me, ‘This is so strange. Jeff was just giving me your phone number, and they told me you were in the next room.’ Then George asked me where I was going. I told him I was going home. He asked me if he could go with me. So he came home with me and spent the holiday with me and we became good friends.”

More than good friends, really. Harrison decided that the two had shared past lives together, and he told Petty that. “We got to be really close almost immediately. George told me, ‘I’m not going to let you out of my life now.’ And he never really did.”

The two would find any excuse to hang out, spending family holidays together and eventually working on what was intended to be a solo album for the former Beatle but eventually became the Traveling Wilburys’ first album.

Call it a payoff for a landlocked boy from Northern Florida, who convinced himself back in 1968 that if he pursued his dream of being a musician that he might just be able to do what he loved. “I took the road thinking I may not have as nice things as other people are going to have, but I have this and I love to do this,” he said.

“I wouldn’t say I was pursuing a career, really,” he explained in 2016. “I’m just enjoying playing music. It’s really convenient to have an audience, and I have a lot of music in me yet. I have a lot in my head and I want to get it out.

“I do know we’re running a little slower, in some ways,” he said. “Though I’m told I’m running too fast,” he added. “But I always will, probably.”

“I turned anger into ambition,” he told one interviewer. But years later, he insisted that he was able to tame his demons. “I’m not as bad as I used to be,” he said to me in 2012. “I didn’t even realise how wound up I was. I could get so angry. I don’t think I’m like that as much.

“I still have my moments where I can get like that. I can get really frustrated with all the shit involved with business. Every day there are more fires to be put out and more things that have to be dealt with, and I don’t really want to spend my time doing that, so sometimes that can get me really annoyed. But with everything else I think I’m more at peace. At least I hope I am.”