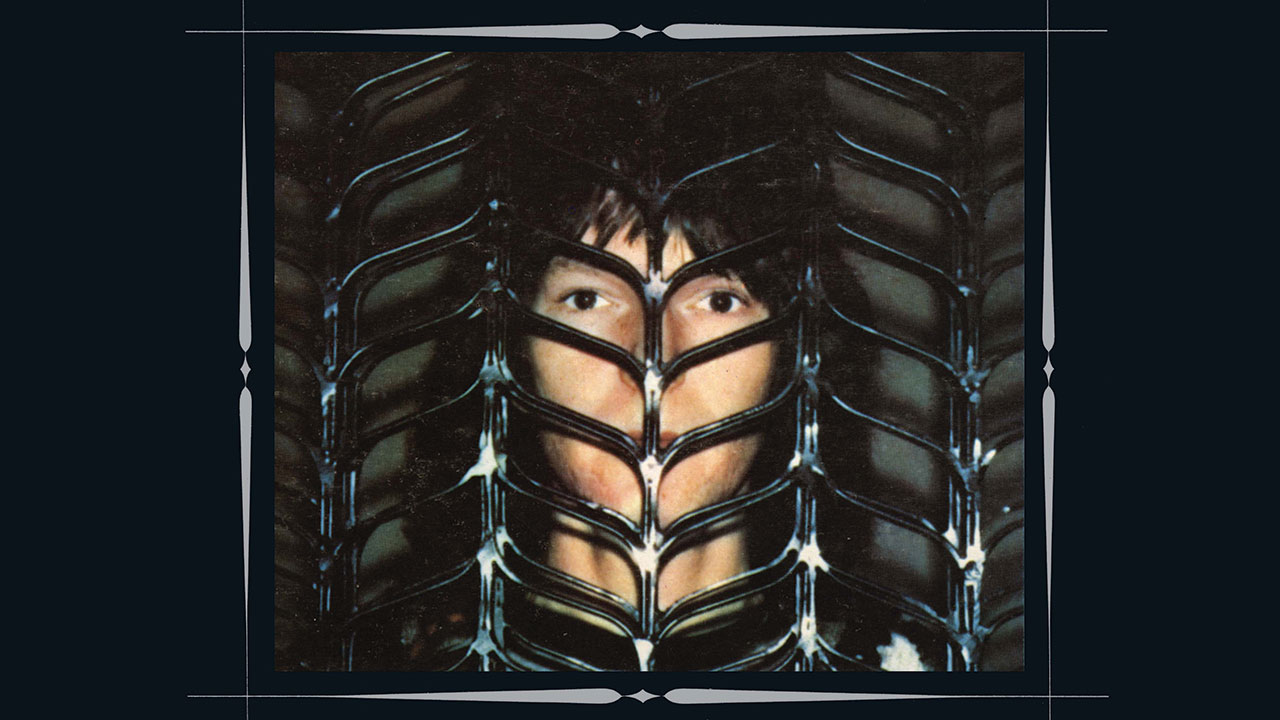

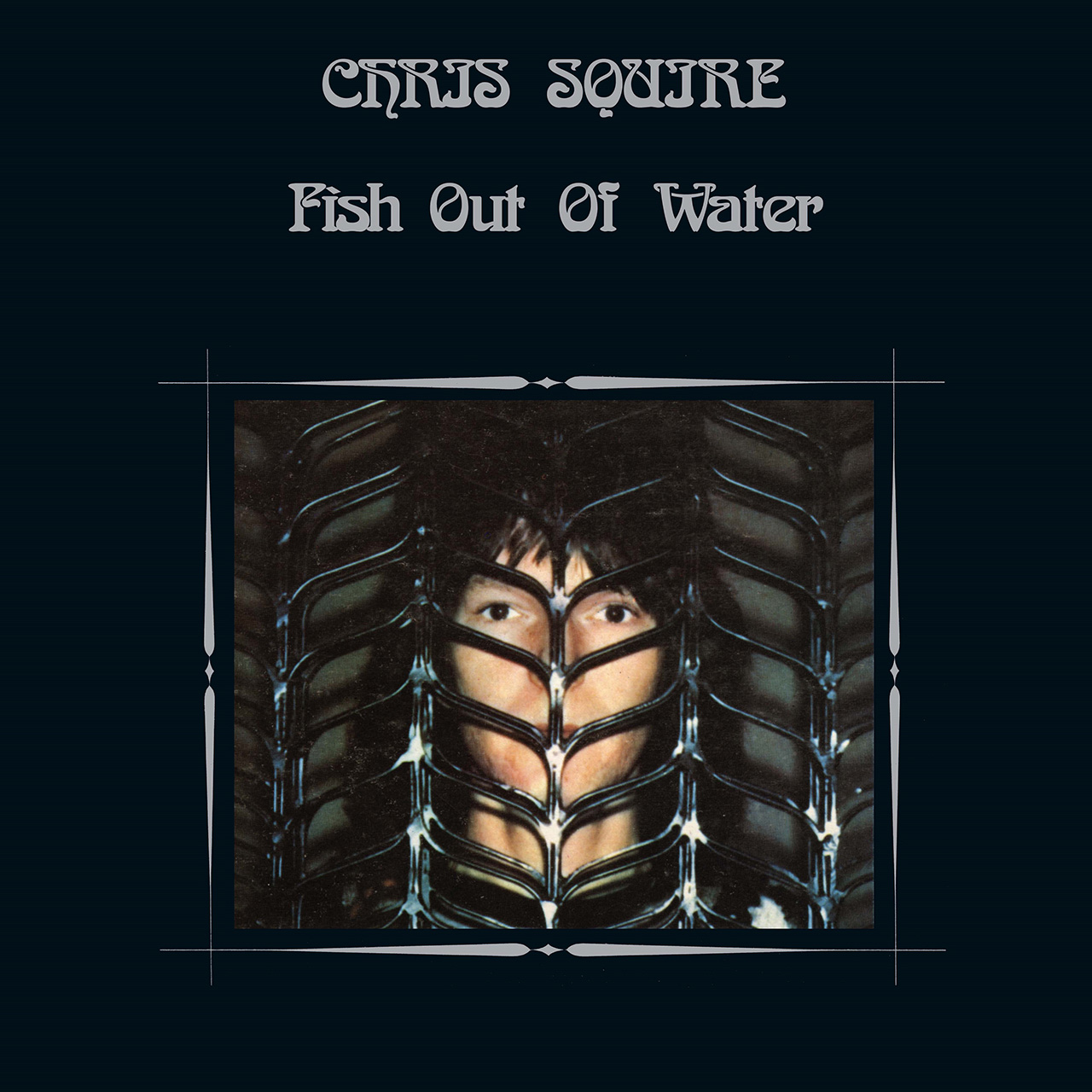

Three years after Chris Squire's untimely passing due to cancer in 2015, Prog investigated the making of his debut solo album, Fish Out Of Water, when a brand new deluxe box set of the album, origjnally released in 1975, saw the light of day.

Chris Squire is checking the time and he’s smiling. It’s long gone midnight, deep within St Paul’s Cathedral, where he’s watching recording engineer Gregg Jackman and a couple of assistants placing microphones and checking levels.

Advising them as to the best spots within the vast, resonant building is Barry Rose, the newly appointed sub‑organist who is about to play the third largest pipe organ in Europe. Joining Rose at the keyboard, Andrew Pryce Jackman, Gregg’s brother, goes over the details of the score he’s written as Rose adjusts his headphones.

Looking upon this nocturnal activity, Squire recalls when he and the Jackman brothers were choristers at St Andrew’s Church in Kingsbury. They had been under the direction of Barry Rose, then their energetic choirmaster, and had even performed in this very building. Now, in the early hours of a summer morning in 1975, here they all are once again, old friends reunited in the making of Chris’ first solo album. This feels special.

Nervous smiles, a burst of laughter and a last-minute cough. A final tweak on the four-track recorder. Glancing back and forth, nods of the head exchanged. Now, everything goes quiet. There’s a count in and the backing track of Hold Out Your Hand fills the headphones and Barry Rose begins to play the notes before him. Squire suppresses a deep chuckle of delight as the jubilant ascending chords fill the air of this cavernous, sacred space.

It’s a spine-tingling moment. In his head, he sings, the lyrics especially apt: ‘You can feel it coming/With the morning light/And you know the feeling’s/Gonna make you feel all right.’ As the rhapsodic arpeggios and lines ripple and reverberate out from the pipes around the building, the boy who grew up in Salmon Street, known to his bandmates and millions of fans around the world as The Fish, is in his element and smiling.

It’s sometimes easy to forget the velocity at which Yes travelled in the early 1970s. A dizzying schedule of increasingly larger tours with more prestigious venues followed each newly released album. Despite being locked into this apparently never‑ending treadmill, the creative bar was incrementally raised between 1971’s The Yes Album through to 1974’s Relayer. Even allowing for the critical backlash and controversy surrounding 1973’s Tales From Topographic Oceans, Yes maintained their reputation as the most innovative and ambitious band of their generation.

In this context, the novel idea that all five members of the group would take time out to record separate solo albums, which would then be released over the course of a year, could be viewed as either audacious or the hubris of over-inflated ego. Executives at Atlantic Records were underwhelmed, worrying, perhaps understandably given the volatile nature of the line-up, that Yes were in danger of diluting what was a highly successful formula.

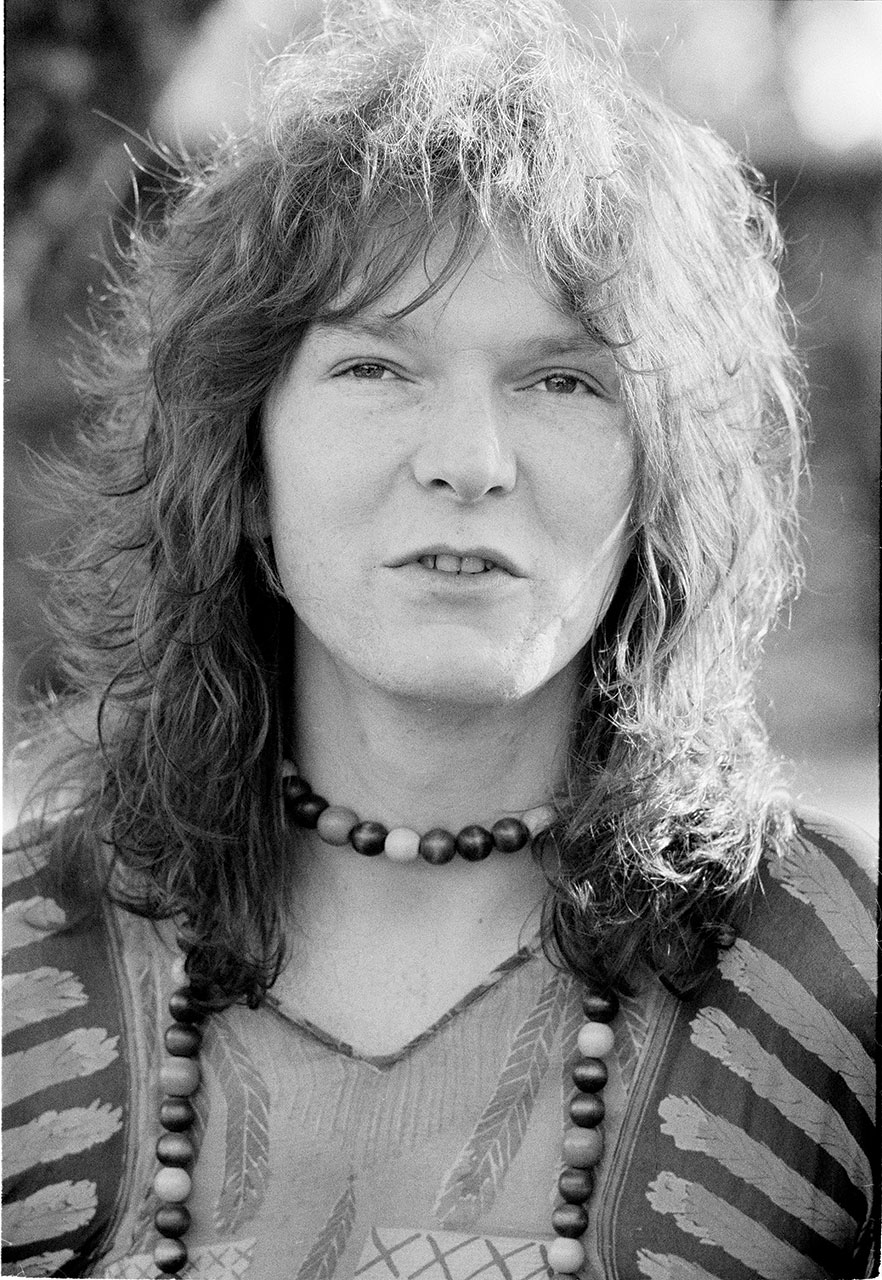

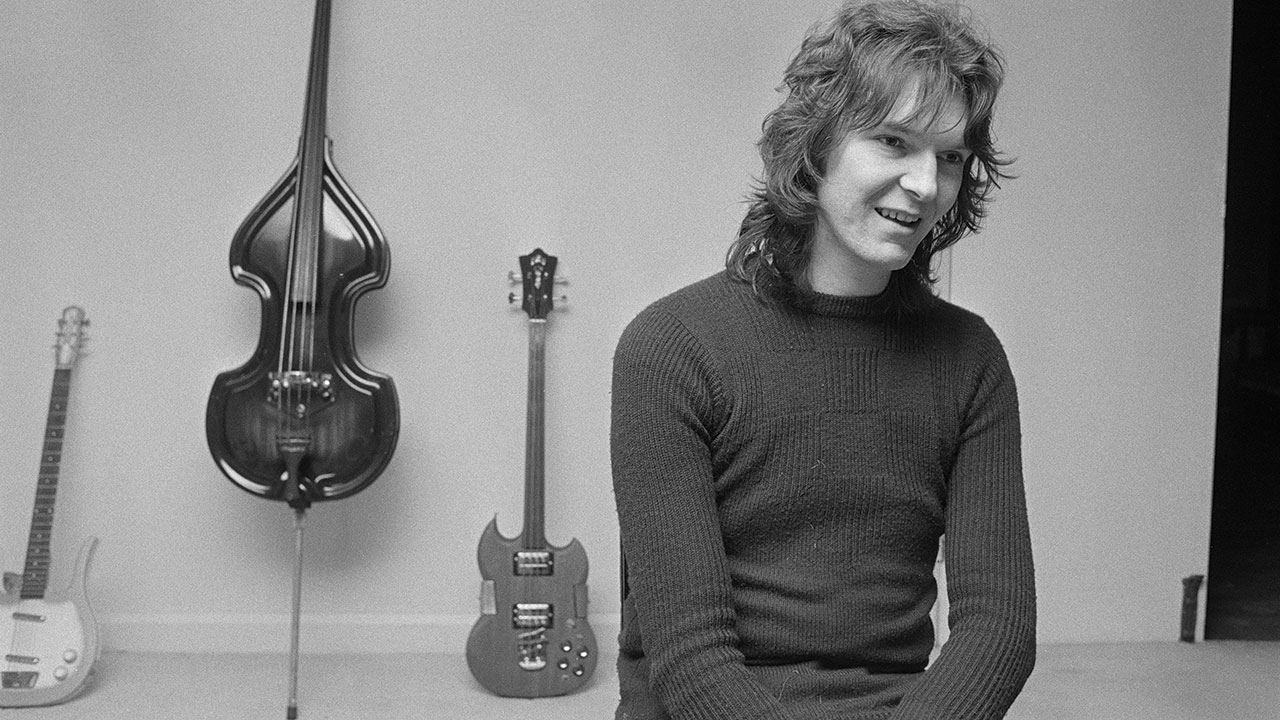

For Chris Squire, the trappings of that success provided him with New Pipers in 1972, a sprawling mansion at Virginia Water in Surrey, and later, like any self-respecting member of rock’s aristocracy, the installation of a bespoke recording studio in the basement. It was here, between tours with Yes, that Fish Out Of Water slowly took shape.

It might have been assumed that any Squire solo album would be an elaborate showcase for his bass playing, using The Fish (Schindleria Praematurus) from Fragile as a template. Yet the core of the album was composed at the piano, in the company of his old friend and former bandmate in The Syn, Andrew Pryce Jackman.

If Yes releasing solo albums represented a kind of safety valve through which the band could let off individual steam, for Squire it was also a means to renew and reconnect the creative bonds in a project that brought out the best in each other. The intention was to build something grand and epic in scope, and Andrew Pryce Jackman’s skill as an orchestral arranger meant that whatever Squire conceived, his old friend was the man who could make the vision a reality.

Andrew’s brother, Gregg, engineered the sessions between his duties at Morgan Studios and remembers being called to work on the album after Eddy Offord became unavailable.

“I think I was 21 years old and really not experienced enough to be doing this record, but the young have a brave heart, so I gave it my best shot. Andrew and Chris always seemed to have faith in me,” he says.

The young engineer also recalls that the sessions weren’t held at regular hours. “Chris was the only bloke I ever knew who could be late in his own house. I would turn up with Andrew at maybe midday and we’d find things to do until Chris decided to get into the studio. This might be as late as seven in the evening.”

Working on the album was Bill Bruford, who’d quit Yes for King Crimson in 1972. Following Robert Fripp’s unilateral decision to disband the group in 1974, he’d been enjoying life as a peripatetic drummer.

Bruford was delighted to be hired by his old bandmate. “Chris was really my first bass player, as it were,” he says. “So I didn’t really know what bass players did or what they might want to do. I didn’t think it weird at all that he seemed to be adopting a rather plectrumy, trebly sound on his bass, and that he wanted it to be as predominant as a guitar part. He became very good at counterpoint so the bass parts had a life of their own. They were something you could sing or hum along to in their own right.

“You’re supposed to have this empathetic relationship with the bass player but that’s a very old fashioned idea that comes along really with words like ‘gig’, ‘pad’, ‘charts’ and ‘rhythm section’. I’m not sure I ever thought I was in a rhythm section much, and I don’t think Chris did either.”

Bruford’s part in the recording began at the end of February 1975, extended through 13 sessions in March and then a final four dates in early April. He recalls that the material at that stage was very malleable. “It was just like a Yes record. There weren’t any bits of paper. Chris played me a bit of a song and I said, ‘Well, I could do this,’ the usual kind of thing. We only knew one way of working together. Andrew was effectively the musical director and he would have been noting bits down because he knew he was going to have to orchestrate it all later. So we did have a real musician present, thank God!”

Another visitor to New Pipers was keyboardist Patrick Moraz, who drove in from the rat-plagued basement flat that he still rented in Earl’s Court, just as he had done during the making of Relayer. Squire had a certain presence, says Moraz.

“He had a kind of ‘halo’ around him, if I can put it like that. As quiet as he could be compared to Jon or Steve, he was extremely forthright in telling you what he wanted from you. His instructions could be extremely meticulous in terms of the arrangement, the sound, the balance and so on.”

Moraz’s incendiary Hammond solo on Silently Falling was judged by Squire to be “one of the best I’ve heard”, and, like his idea to play Minimoog bass, was ample proof of Moraz’s inspired contributions to the process. However, as proud as he is about his work on the record, Moraz has one regret – that the album didn’t lead on to a further collaboration. “There was an inspirational empathy between Bill, Chris and myself, you know?”

Although Moraz and Bruford would later work together, touring and producing two albums together in the 80s, it’s obvious that Moraz sees a follow-up album as ‘the project that got away’. “If only we had been able to do a trio album, just the three of us. Man, it could have been absolutely unbelievable. Unbelievable!”

While on tour, the members of Yes would play each other their individual works in progress. This had a galvanising effect, according to Moraz, who also worked on Steve Howe’s Beginnings. “What Chris did was create a kind of momentum and set the bar for each of us to come up with a solo album that was as good as his.”

From the exuberant St Paul’s Cathedral organ lines of Hold Out Your Hand, the pastoral interludes within You By My Side, the driving rock that merges into a Beatlesesque coda on Silently Falling, Lucky Seven’s jazzy undertow and the surging romanticism of Safe (Canon Song), with its orchestral splendour and spectral phase-shifted comedown, the range and reach of Fish Out Of Water is impressive.

Coming out at a time when extended musicality was an integral part of the progressive rock landscape, it’s an album that not only holds its own next to any albums by Yes’ contemporaries, but also, whisper it, towers above the other solo releases of his bandmates.

Released a month after Howe’s solo album in November 1975, Fish Out Of Water found its way into the charts on both sides of the Atlantic. While Squire’s virtuosic playing is clearly evident, it’s serving the needs of the song rather than placed centre stage.

“Those were really pioneering days – none of us knew exactly what we were doing,” Squire remarked in 2007.

Hearing the notes leap from the pages of Pryce Jackman’s notation and into the air was a revelation for Squire, as he watched his friend conducting the orchestra at Morgan Studios in one three-hour session.

“Being able to write it down on the manuscript and just know what it sounded like by looking at it was amazing,” Squire said of Pryce Jackman’s work. “Although later I met people who could do this, Trevor Rabin being one of them, Andrew was the guy I grew up with and I thought, ‘God, it’s amazing he can actually do this!’”

Perhaps not surprisingly given their close working relationship, Squire offered Pryce Jackman co-writing credits for the record, though this was politely declined.

“Andrew never promoted himself and you’d never see articles in the press about him,” says Steve Nardelli, vocalist with The Syn. “Andrew was very modest and so he wouldn’t have minded about getting credit. He was really pleased with the outcome. I know the sessions were tortuously slow sometimes but that’s because they were striving for perfection. But it was worth it. I think it’s one of the greatest albums ever made.”

Brimming with a confidence that comes from being at the very top of his game, the blending of pop, classical and rock music into one coherent, thematic statement remains a considerable achievement, and one which Squire was immensely proud of. There was talk of a follow-up, though the endless touring cycle and increasingly internecine politics within Yes meant Squire’s priorities lay elsewhere.

The death of Andrew Pryce Jackman in 2003 robbed Squire of a dear friend, and the opportunity to create something with similar aspirations. Perhaps the fact that Fish Out Of Water is a one-off, something Squire was never able to return to, is the very thing that gives the album its remarkable presence and power.