As Britain baked in the long, hot summer of 1976, progressive rock’s place in the sun was under threat. Yet some of those self-same prog fans that the burgeoning punk movement was about to render deeply uncool would, in due course, reinvent the genre, infused with its own injection of vigour and DIY attitude.

And it was on June 15, outside the inauspicious setting of Stafford’s Bingley Hall, when two such individuals had a fortuitous meeting.

Sixteen-year-old Michael Holmes had made sure he turned up early to get a spot down the front at Genesis’ first UK date outside of London on the Trick Of The Tail tour. So too had another teenage fan, Peter Nicholls from Manchester.

“I was sitting outside waiting for the doors to open,” Nicholls recalls, “And me and Mike got talking somehow. A lucky happenstance really – if either of us had been half an hour late we’d never have met.”

They began writing to each other and swapping bootlegs, and when Mike mentioned he played guitar, Nicholls told him he was a singer (“A complete lie – I’d never got past posing in front of a mirror with a hairbrush!”).

Holmes, along with keyboard player Martin Orford soon formed The Lens, occasionally aided by Nicholls on forays south, but after a few years’ jamming, IQ was born.

“We decided around 1981 that if we were going to do anything we had to move to London,” says Holmes. With all but drummer Paul Cook relocating, four lads – including bassist Tim Esau - shared a two-bedroom flat in Kensal Green, surviving on scraps discarded by bakeries at the end of the day.

“It was like The Young Ones before The Young Ones,” grins Nicholls, “but for all the deprivation we put ourselves through, it consolidated the group spirit – it was us against the world.”

That strength of purpose would be crucial in such straitened post-punk times.

“Prog was such a dirty word then,” says Holmes. “It really wasn’t something you admitted liking in polite company.”

Nonetheless, there were friendly refuges out there. They made Soho’s Marquee their home-from-home and began to pick up regular support slots, for which they handed out flyers at other bands’ shows. This experience informed the frantic, sometimes schizophrenic tempo of their music.

“The music wasn’t all that punky,” admits Holmes, “but the attitude was onstage. We regularly had stage invasions at the Marquee.”

“We played some pretty rough places,” recalls Orford. “You couldn’t play noodling 30-minute guitar solos because you’d have big skinheads grabbing the mic off Pete. You had to do some stuff a bit more upbeat or some of those audiences would have killed you.”

By early 1983, IQ, Pallas, Pendragon and Twelfth Night, were building a modest but loyal following, and talk of a neo-progressive movement was being bandied about in sections of the music press. But one band had stolen a march on them all. Marillion’s Script For A Jester’s Tear was released on EMI in March 1983 and they quickly became the focal point of the new vanguard – a blessing and a curse for IQ.

“Once Marillion were signed they were well-promoted,” says Cook, “but no other label was interested in the other bands on the prog circuit.”

“I remember being told there was no room for another major label prog band,” says Orford, “so we might as well forget being signed.”

It was then that they spotted an advert in the back of a music paper offering a package deal: £1,500 for five days in a “top London studio”, assisted by an in-house engineer, 1,000 vinyl copies of the album, and – the clincher for the Beatles fans in the band – mastering at Abbey Road. So it was that they took that most punk rock of moves and decided to release their own LP. Just one small problem: they’d struggle to rustle up 1,500 pence. So they borrowed the sum from Cook’s father.

Four of the days they booked in North London’s Flame Studios were set aside for recording, and one for mixing.

“We had so little time that my vocals were mostly first and second takes,” says Nicholls, but that was the least of their worries. The structure of the album’s 20-minute opener The Last Human Gateway still wasn’t finalised, and underlying tensions between Holmes and Orford inevitably came to a head.

“I always had it in my head that Gateway should have a big reprise of the Mellotron flute intro at the end,” says Holmes, “and Martin really didn’t want that. One day after recording we were having a screaming row, and I got in our van, and reversed into another car. The owner got out and asked what I was playing at. I just lost it and started shouting at him. And he got back in and drove off, terrified!”

“Me and Mike never got on,” admits Orford. “On one occasion he even pushed me in the Thames. Still, we got some good music out of it all…”

Not everyone thought so, though – not least Mel Simpson, Flame Studios’ in-house studio engineer.

“He didn’t quite come out with it in so many words,” says Holmes, “but he did say, ‘Are you really sure you want to press 1,000 of these? Surely you won’t sell that many.”

With time at a premium, there was little room for perfectionism, even though many of the pieces were composed in time signatures that even the band themselves found daunting to pull off.

“There’s some pure maths going on in parts,” admits Orford. “There’s a 17/8 section in The Enemy Smacks, then another bit where every 21 beats it matches up. But it still works as a riff.”

The breathless amphetamine rush of Through The Corridors and the staccato, keyboard-driven dreamscape of Awake And Nervous built the pace of a record that, even now, sounds thrillingly charged.

“I think we knew that a different level of energy was expected at that time,” says Orford, “so we created it within a progressive rock framework.”

The album’s five tracks did include one striking pace change, though. A piano instrumental slipped into the middle of side two is a beautifully baroque, dare we say Chopin-esque, moment of relief. And struggling to give it a name, they naturally plumped for My Baby Treats Me Right ‘Cos I’m A Hard Lovin’ Man All Night Long. Any relation to Spinal Tap’s similarly piano-based Lick My Love Pump is, it seems, purely coincidental.

“We just thought it sounded humorously inappropriate,” admits Holmes.

Most importantly, My Baby… was quick to record, and further added to the wildly contrasting tones of dark and shade that make this record so intoxicating.

Meanwhile, Nicholls’ lyrics, recounting an internal struggle against ‘The enemy… the beast in me’ were also a conscious departure from the more clichéd prog territory.

“I was aware of the Tolkien element to some prog lyrics,” admits Nicholls, “And I strove to avoid that. Anyway, the albums I always connected with were more about internal stuff, not elves and pixies.”

If the battles going on in Nicholls’ head were spilling onto the record, the in-band tensions did too, particularly on mixing day.

“We were all standing over the mixing desk, each trying to turn our own parts up when no-one was looking,” recalls Nicholls. “Then it would all be ruined and we’d have to start again.”

Mel Simpson wasn’t quite so precious. To Orford’s enduring chagrin, the engineer performed his own rather injudicious edit on parts of the album.

“Part of a dual synth lead part went completely missing at the end of The Last Human Gateway,” he says. “I asked to put it back in and he said ‘Oh, there’s no time for that!’”

Nonetheless, Mike and bassist Tim Esau still had the treat of going to Abbey Road for the mastering the following week.

“It was great,” remembers Holmes. “We only had an hour there, but after being cooped up in a tiny studio, we thought, ‘We’ve hit the big time!”

The thrill endured as they retired to their Kensal Green flat to listen in awe to the finished product, then played their first headline show at the Marquee on September 15 to coincide with the release date. But the album’s sleeve wasn’t finished, so initial copies were sold with a plain cover.

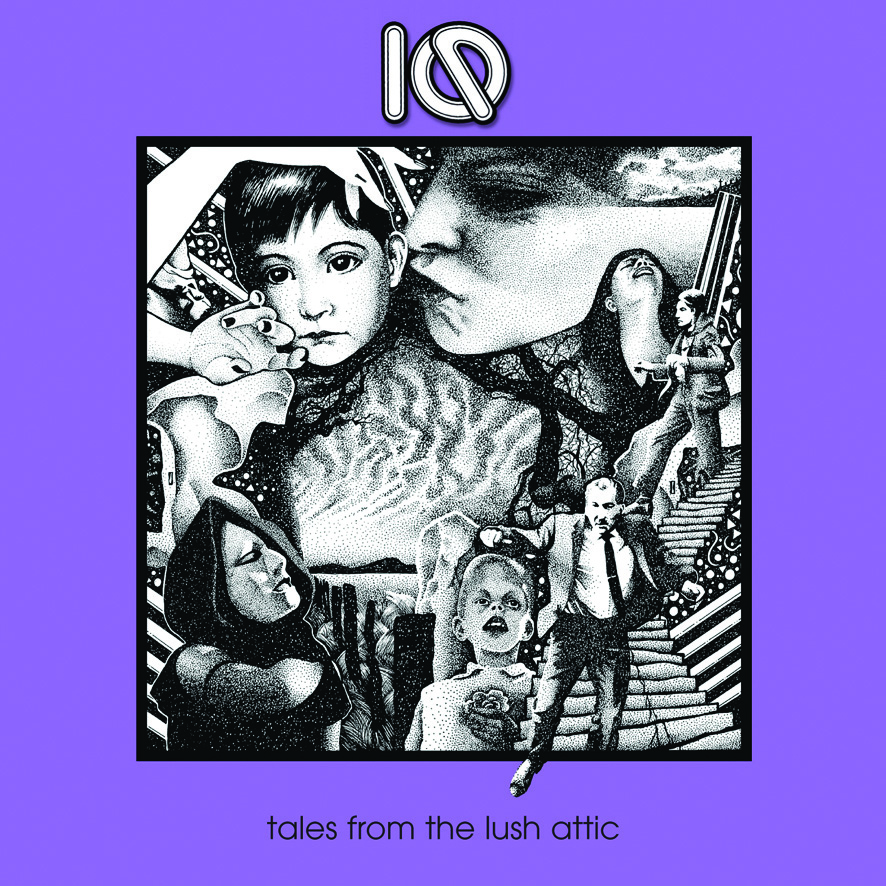

That was a shame since Nicholls’ artwork soon became an important part of the band’s visual identity, the sleeve of Tales… depicting a maelstrom of images inhabiting the songs.

“I can’t think of that album without Peter’s artwork,” says Cook, and Nicholls admits that the visuals were an essential part of the whole package: “I thought, ‘This music is really hard to get into on first hearing,’ so I felt it was important have some sort of

visual impact. So I came up with the costumes and make-up, and I certainly didn’t want anyone else’s art on the cover…”

The album was favourably reviewed in Sounds and Kerrang! among other places, with the former calling it “a debut disc that dazzles with its dexterity”. And contrary to Simpson’s expectations, Tales… has gone on to sell an estimated 60,000 copies – “pretty good for a little independent release”, says Holmes.

Those sales were generated over several years as IQ slowly gained new generations of fans. Their 1985 follow-up album, The Wake is regarded by many as an even better record, and despite several line-up changes since, their standards have rarely slipped, with highlights including 1998’s sprawling double album Subterranea and their last outing, 2009’s more immediate Frequency. Soon after that album, Paul Cook rejoined the group after a four-year absence, and in 2011 original bassist Tim Esau also rejoined after having left in 1989.

The feeling of having come full circle has now been underlined by the reissue of a remixed, deluxe version of Tales… on Holmes’ Giant Electric Pea label in March of this year. It still proved a tricky undertaking, involving, oddly enough, the baking of the original masters.

“The tapes had been stored, appropriately enough, in someone’s attic,” Holmes explains. “The oxide on them gathers moisture, which makes it disintegrate, and to dry them you bake the tapes at a very low temperature for three days, then you have around a month to transfer them to more up-to-date media. It’s still a risky process, so it was pretty nerve-racking. Thankfully, it all turned out fine.

Omissions like Orford’s keyboard part were restored, and the original vision was finally achieved for an album that Holmes admits he had come to enjoy a “love-hate relationship” with.

“I have to say they did a remarkable job,” says Orford, who retired from music in 2007. “They made it what it should have been in the first place. It now has a production that matches the songwriting. So the story has a happy ending, really.”

This article originally appeared in issue 36 of Prog Magazine.