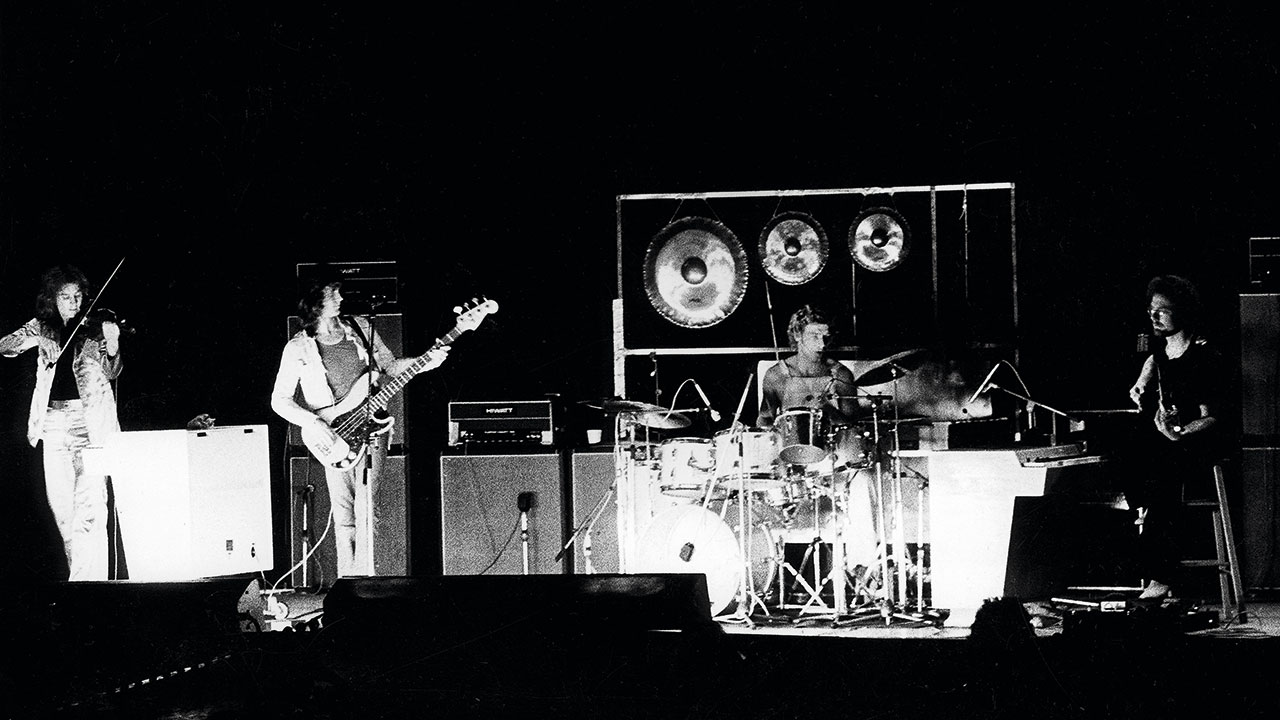

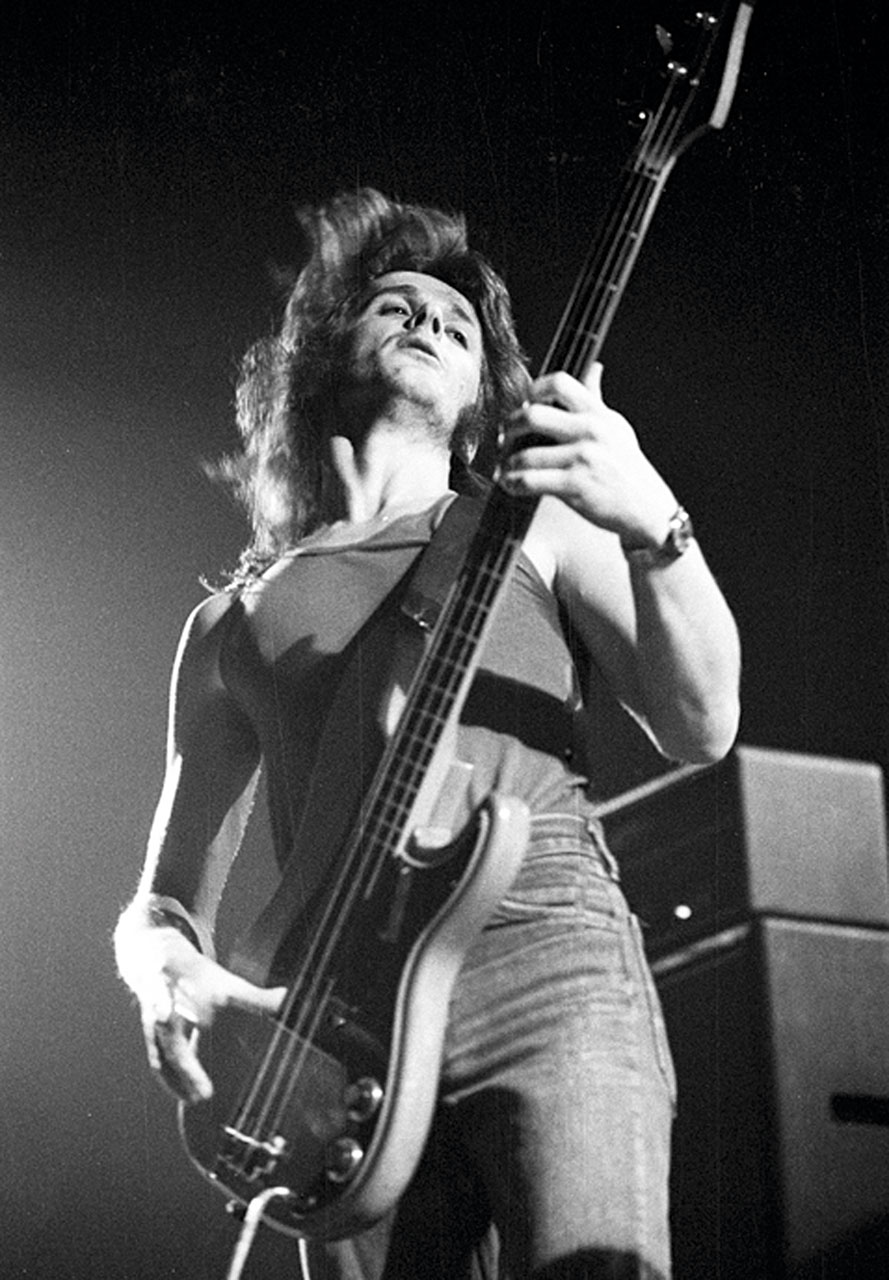

Palazzetto dello Sport, Rome, November 1973: King Crimson have just finished soundchecking for this evening’s sell-out gig. As Robert Fripp, David Cross and Bill Bruford depart to ready themselves in the backstage area, John Wetton is fine-tuning his settings. “The soundcheck over, I gave my bass to our roadie, Tex, and was just about to leave the stage when this 15-year-old girl came up to me. ‘My name is Lorena,’ she says. ‘My brother’s here because I need a chaperone. I’d like to marry you.’ What the fuck?”

Back then, at home and abroad, there were legions of girls charging about from venue to venue, hurling declarations of undying love and more in the direction of their favourite pop idols… but King Crimson? Really? Wetton admits to being taken aback, not necessarily by the demand so much as the potential danger of the situation.

“I laughed a bit nervously but she told me that she was serious and her brother would attest to that. ‘I have a formal request from my family that you marry me.’ I managed to placate the brother, who looked like he would’ve murdered me on the spot if I’d said no, and for a few moments I played along with it. It was extraordinary. There was no security because the gig wasn’t anywhere near starting. Then I went and got somebody from the management to tell the girl and her brother that we would consider her request. She was deadly serious. Amazing, really. Italy in 1973 didn’t have a progressive feminist atmosphere. Guys were still lying on the pavement trying to look up miniskirts at that time. For this girl to get it together, get her brother down to the gig and, with her dad’s permission, make a formal request that I marry her… I mean, it’s extraordinary. Took me completely by surprise! Stuff like that would happen to Crimson all the time.”

Despite their cerebral image, King Crimson were no strangers to the occupational hazards of a band on tour experiencing road fever. Although they never quite got as far as throwing TV sets into swimming pools or trashing hotel rooms, they were certainly fond of indulging in some boisterous behaviour. “Like the time we were in Avignon,” says the bassist, who recalls Crimson’s visit to a rustic auberge on the outskirts of the beautiful old town in the south east of France. “Crimson stayed in the same hotel that I’d stayed in as a member of Family when there’d been a food fight there. A food fight for Family was an every-night occurrence, but not for King Crimson.”

After checking in, Wetton and company went down for dinner. “I just happened to mention about Family’s food fight and the whole thing broke out again with Crimson! Everyone in the band and crew flinging food at each other – ice cream, pâté, foie gras, you name it. The poor maître d’ was standing there utterly bemused. He wasn’t angry, he was just thinking: ‘What the fuck is it with these guys? We had another English band do the same!’ Thankfully he didn’t twig that I was the common denominator!”

While that kind of behaviour wasn’t uncommon for touring rock bands, it’s fair to say King Crimson never had that reputation. “We get very bad press in that respect,” Wetton explains. “We’re not rock’n’roll; we’re too studious or something. That’s not quite accurate. We just did it in a different way and we did it where there weren’t any journalists, like in Avignon.

“Crimson were actually very rock’n’roll in fact. There was plenty going on, I can assure you of that. We had our fair share of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, but not in the same way that Black Sabbath might have done, and we weren’t tarred with the same brush. Because of the technicalities in our music, people probably expected Crimson to be more studious or more monkish. We were more monkfish than monkish, I would say!”

There are other tales of far more lurid backstage antics from Crimson’s extensive catalogue of live dates, which are not quite repeatable. But any consideration of headlining bands of the era will inevitably uncover rock’n’roll’s close cousins, sex and drugs, lurking close by. Alongside such carnal cavorting, the consumption of cocaine would eventually become commonplace – though not, it should be noted, by everyone in the group.

‘What plays on the road stays on the road’ might well have been the golden rule for many groups of the day, though it seems nobody had passed that memo on to Robert Fripp. Just weeks before Wetton’s marriage proposal in Rome, the guitarist went on record in both the Melody Maker and the New Musical Express to declare his availability to as many young ladies as might be interested. This was despite admitting the numbers he’d already had congress with as being, in his own words, somewhat excessive. “Sexuality pervades my work,” he told bemused journalists at the time.

You might not think of Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, Part Two as the modern-day equivalent of Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! or the ideal music to improve your seduction technique, but the makers of the soft-porn movie Emmanuelle evidently thought it couldn’t hurt, ripping off the track’s thrusting themes as an ideal accompaniment to their on-screen action. They ended up in court and lost their case. Even today, Fripp still receives a trickle of royalties resulting from the movie’s soundtrack.

Of course, in 1973 King Crimson weren’t simply touring in order to pursue rutting opportunities. There was the not inconsiderable matter of recording a follow-up to Larks’ Tongues In Aspic. The album had sold well but the band were less than happy with the results of the time they had spent during January and February in Piccadilly’s Command Studios. “Collapse Studios more like – that’s what we used to call it,” shudders Wetton.

Despite the classic nature of the material and many inventive moments peppered throughout LTIA, the Crimson camp felt that whatever magic had touched them as they played in concert during the winter of ’72, the recording of the album in the New Year had quite simply failed to capture any of that power or intensity which had moved not only the band themselves, but also many commentators and fans.

Putting a brave face on their combined disappointment, by the time the album hit the shops, the quartet were already on their way around the UK, Europe and, in mid-April, the USA. The Crimson that returned to the UK in July ’73 was not only tired after notching up over 60 gigs, but also in dire need of new material to refresh the setlist and prepare for a new album.

Reconvening after a three-week holiday, spirits and tempers were frayed, rather than rested. What had been a break for some turned out to be a busman’s holiday for Fripp, who emerged from his Dorset cottage with Fracture, The Night Watch and Lament.

As the group worked on the new tunes, bad tempers flashed. According to Bill Bruford, Crimson’s writing processes were exercises in “excruciating, teeth-pullingly difficult music making. The tunes Robert has written all the way through, such as Fracture, these are good, and had there been greater output from Robert, we’d have got on quicker and faster. Robert’s always done this. He’s started off these bands with one-and-a-half tunes that point the general direction, and Fracture would have been one of them.”

“I was never given the time to write,” counters Fripp. “The band had a three-and-a-half-week holiday. I had three days. I recall on another occasion saying to the band that I needed time to write, rather than just continuing to rehearse. Bill, in a schoolmasterly and rather grudging fashion, would only agree if I really would do the writing, as opposed to what he implied was goofing off.”

The gnawing antipathy that became a defining characteristic of Fripp and Bruford’s subsequent professional relationship first surfaced in these rehearsal sessions, sewing the seeds of the band’s demise a year later.

Putting their differences aside, Crimson took to the road with their newly composed repertoire and their near-telepathic ability to create complex and nuanced improvisations off the top of their heads. When they played at Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, a mobile recording studio captured the band in full aleatoric flight.

Though many rock bands of the day filled their sets with instrumental music, these usually boiled down to extended solos over relatively straightforward blues-based changes (perhaps with the exception of German experimentalists Can). Even away from jamming-orientated groups, the rhythmic and harmonically complex improvisations Crimson specialised in between the winter of 1972 and their break-up in 1974 drew more upon the atonal and dramatic vocabulary of contemporary classical music as a reference point than any of the prevailing trends in the scene.

While Crimson may have been contemporaries of ELP, Genesis and Yes, as Fripp puts it: “King Crimson were nothing like the other bands of its generation. More accurately: the other bands, all more popular, liked and commercially successful, with their own triumphs and failures, were nothing like King Crimson.”

Back in the UK in January 1974, and with three new tracks in the can at George Martin’s AIR Studios, the band sifted through the many live multitracks from the tour, choosing the best improvisations and scrupulously editing the tapes to remove any hint of audience noise or applause. It was impossible to tell what had been improvised in concert and what had been recorded in the studio.

When it was released in that spring, not even the record company knew that Starless And Bible Black was essentially a live recording. Such secrecy by the band might have resulted from knowing that record labels paid a reduced royalty rate on live albums. The truth only emerged several years after Crimson had split up.

John Wetton is proud of the results: “For me, it shows us moving into another dimension as far as being a band is concerned. We’d found our feet; we’d been on the road for the best part of a year. We knew what we wanted to do and we were getting creative. Not only is the album chronologically the bridge between LTIA and Red, but it’s also a bridge in many more ways. We were getting more experimental, trying different recording techniques, really screwing with the system, removing applause from live tracks so they sound like studio tracks – the exact opposite of what people do today where they add applause to a studio track and pretend it’s live. We’d removed the audience because that was the only way we could get the atmosphere we were after. Before Red, we could never recreate that kind of power in the studio – it just wouldn’t happen. You’re in a sterile environment, whereas on stage you’d got all that air and people and you’d got energy.”

The bassist looks back on the period in which the album was made with real affection – even that impromptu marriage proposal he hotfooted it from in Rome. Wetton was recently asked to rummage through his collection of memorabilia for anything that might be useful in the forthcoming Starless box set. There, among the accrued detritus of over four decades spent on the tour bus, he found a ticket stub for the gig at Palazzetto dello Sport. On the back of it was the girl’s name and telephone number. “She’d be about 55 years old now,” he smiles.

This article first appeared in Prog issue 49, December 2014