In 1969, Chris Welch was the star writer for Melody Maker, then the most influential and prestigious music paper in Britain. He’d been there when Jimi Hendrix first set fire to his guitar at the Speakeasy, hung out in the studio while The Who wrestled with Tommy, kept Bob Dylan waiting in reception for an interview while he finished his lunch, driven Rod Stewart home from gigs in the days when Rod was too poor to afford his own wheels. But Chris says he never – ever – heard anything like this.

"One of the younger writers brought an early, pre-release copy of the album in, and played it on the office stereo – and it just leapt out at you; it really did feel like a great leap forward in terms of the sound you could actually get on a record. And that was just the first track.”

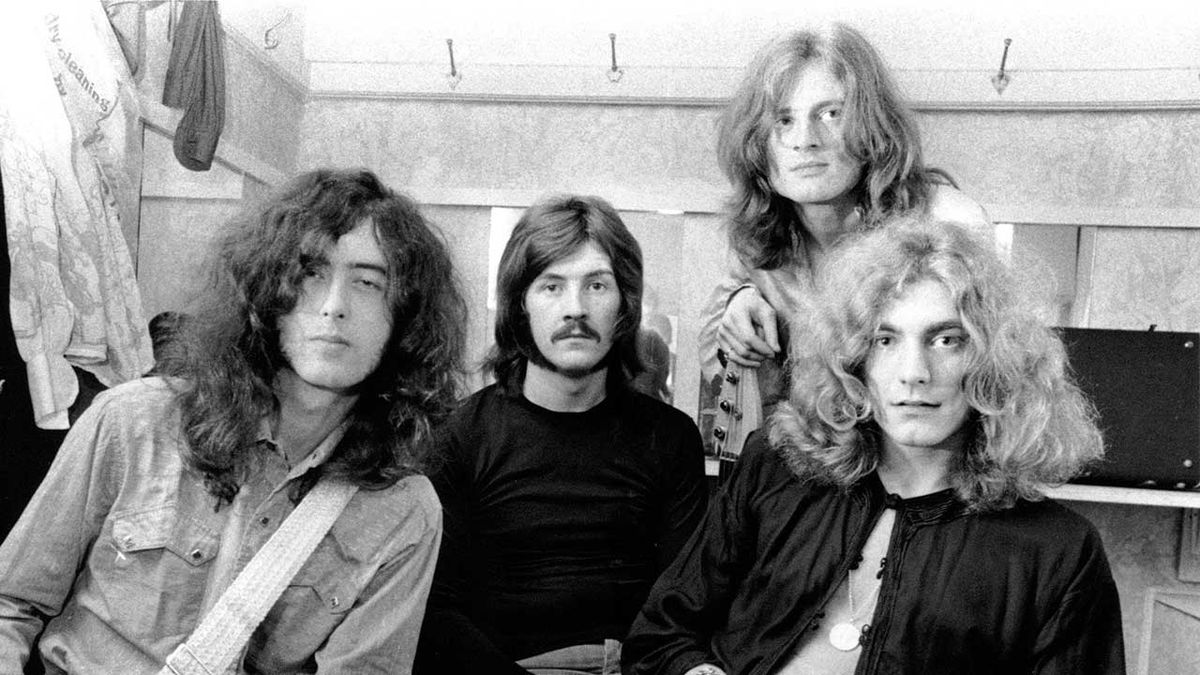

Forty years later, you can still hear the awe in his voice. But then, 40 years later, you can still feel the energy crackling when you play the album he’s talking about: the eponymous debut from Led Zeppelin, released in Britain in March 1969.

Already available in America since the start of the year, despite attracting some less than favourable reviews – notably, from John Mendelssohn in Rolling Stone, who damned Led Zeppelin as the poor relation to Truth, the band offering “little that its twin, the Jeff Beck Group, didn’t say as well or better”, describing Jimmy Page as “a very limited producer and a writer of weak, unimaginative songs”, and characterising Robert Plant’s vocals as “strained and unconvincing shouting” – Led Zeppelin’s debut album was already on its way to becoming a sizeable hit on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as changing the face of rock music completely.

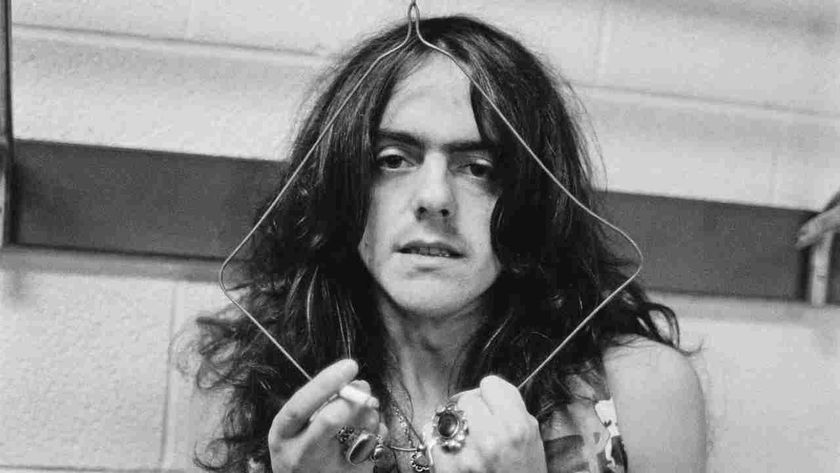

The brainchild of Page, a 24-year-old session guitarist who, somewhat astonishingly, had played on more than half of all the hit singles made in Britain from 1962-66 but who had only recently come to public attention via his late entry into The Yardbirds, the release of the first Zeppelin album could be said to have ushered in the 1970s a year early.

An only child from West London who’d grown up, as he put it, “a loner”, Jimmy Page had always gone his own way: leaving school early to play professionally in a band, Neil Christian And The Crusaders; later dropping out of Art College to become a full-time session player, becoming so successful hat he turned down the chance to replace Eric Clapton in The Yardbirds, then riding high in the charts, recommending his old school pal Jeff Beck for the job instead.

Why endure the endless one-nighters that were then the lot of a touring band of The Yardbirds’ stature, when he could earn more money – far more money - doing as many as three sessions a day in London?

Page was the same age, or younger than the groups whose records he was hired to embellish and improve – from hi-spec artistic fare by Them, Joe Cocker, The Who and several other notables, to low-rent chart-toppers by Val Doonican, Herman’s Hermits, PJ Proby, Engelbert Humperdinck… All of which provided a tremendous grounding in an array of different styles – not just musical, but technical, watching producers of the calibre of Mickie Most, Shel Talmy, Joe Meek and others weave their magic in the studio.

Page’s prowess as a guitarist also benefited hugely from an array of often unexpected sources. Not least his obsession with the work of eccentric Scottish genius, Davy Graham, whose groundbreaking album, The Guitar Player, demonstrated how to go from folk to jazz to baroque, blues, even Oriental and Asian music – without sacrificing any of the edgier sounding techniques then making themselves felt in rock.

Similarly, other Graham disciples like Bert Jansch and John Renbourn, whose album, Bert And John became glued to Page’s turntable as he painstakingly worked out the unusual tunings, esoteric fingerings and strange modal tones. Page had now begun writing his own songs too. Especially when he found out how much money the writers of hit songs could make. Hired to play on a Burt Bacharach session, Jimmy was flabbergasted to see Burt leaving in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce.

The turning point came, however, when the 21-year-old guitarist began an affair with Jackie De Shannon. A successful singer-songwriter from Kentucky who’d written When You Walk In the Room, a hit for The Searchers, then been invited by the Beatles to make a single of her own in London, Page had been hired to play on the session. They ended up back at her hotel, making love and writing songs together – some of which would get picked up by singers like Marianne Faithfull and PJ Proby.

It was also during this period that Page recorded a solo single, She Just Satisfies – Jimmy singing with Jackie on backing vocals. It was not a hit but from now on the session work would pay the bills while Page worked on furthering his career as a songwriter and producer in his own right – as when he and Jeff Beck sat down and started busking up a version of Ravel’s Bolero.

This was during the now famous sessions at London’s IBC studios in the summer of 1966 that would feature Keith Moon on drums, Nicky Hopkins on keyboards and session player John Paul Jones on bass; the same session at which Moony jokingly suggested they form a supergroup – and call it Lead Zeppelin [as in lead balloon]; an idea they all laughed at, but which Jimmy never forgot.

Joining The Yardbirds – as Page did the same year, initially as a temporary replacement for departed bassist Paul Samwell-Smith – had not been part of his cunning plan, more something he did “for fun”. But when rhythm guitarist Chris Dreja agreed to take over on bass, allowing Page to forge a fiery new twin-lead-guitar partnership with his old mate Beck, the fun took on a more serious aspect as the musical possibilities opened up before them.

“It could have been even better than the Stones,” Jimmy recalled. Maybe even more innovative than what Clapton was doing as a soloist in Cream. Could have, would have, should have… except for one thing: the self-destructive streak in Jeff that would also unhinge his later career with his own Beck Group. As Jimmy said ruefully, “Jeff’s his own worst enemy in that respect”.

Within months of Page joining, Beck had bailed out midway through a US tour, complaining of illness, then smashing his guitar in the dressing room and catching a plane to LA, where he met up with a girlfriend. Even then, Jimmy thought he could salvage the situation, help take The Yardbirds to the next level. But then there was producer-manager Mickie Most to contend with.

Unlike Page, who cared about every last detail, Most treated recording sessions as conveyor belts. “Next!” he’d declare, at the end of a take. “I’ve never worked like this in my life”, Page complained. “Don’t worry about it”, said Mickie, before counting in the next number.

When The Yardbirds finally fell apart, out on the road in America, where they remained huge long after their star in Britain had faded, Page was enormously frustrated. Having given up an income sizable enough to buy his own boathouse on the Thames, in order to find acclaim with the band, he was determined to keep the show on the road – even if it meant replacing every other member of the band. Hence: the New Yardbirds – formed within weeks of the final Yardbirds show, in July 1968.

Unable to persuade any of his original A-list targets to team up with him – as Aynsley Dunbar, one of the drummers Jimmy initially approached, put it, “The Yardbirds was already sort of old news by then” – a desperate Page finally settled on a line-up comprising old pal from the session world, John Paul Jones, on bass and keyboards, plus two raw recruits from the Midlands, in the shape of 19-year-old vocalist Robert Plant and his drumming pal, John ‘Bonzo’ Bonham, both late of tried-and-failed psychedelic wannabes the Band Of Joy.

It was a close-run thing, though. Before Plant, Page had been considering Chris Farlowe, but he’d just had a huge hit with Out Of Time, which Page, ironically, had played on. Before that there had been talk of Stevie Marriott, but Page went cold on the idea after Small Faces manager Don Arden threatened to “break his fingers”.

Stevie Winwood was also considered but he wasn’t about to quit Traffic to join the New Yardbirds. And so Page turned to Terry Reid, a young gun-for-hire who also baulked at the idea of trying to forge a career in a group where the appendage ‘New’ made them sound suddenly very old. Fortunately for Page, Reid had a suggestion: a young singer from the Midlands he’d met on the road named Robert Plant. Even so, Page was sceptical. “If he was so good how come I’d never heard of him?”.

Ultimately, however, Plant was the only decent singer out there that didn’t have anything better to do. “I liked Robert,” Jimmy would tell me. “He obviously had a great voice and a lot of enthusiasm. But I wasn’t sure yet how he was going to be onstage.” He added: “The one I was really sure about right from the off was Bonzo.”

Until then, his inclination had been to offer the gig to Procol Harum drummer BJ Wilson, who he’d played with on Joe Cocker’s monumentally heavy treatment of (I Get By) With A Little Help From My Friends. But Wilson rated his chances of success with Procol Harum – who’d arrived the year before with the No. 1 A Whiter Shade of Pale – as infinitely better than the revival of a band that hadn’t had a hit for two years.

Other drummers considered included Dunbar, who had been in the original Jeff Beck Group; Mitch Mitchell, unhappy with Hendrix in the Experience; Bobby Graham, an old ‘hooligan’ session pal; and Clem Cattini, another session pal. One by one they all turned him down.

And so, at new boy Plant’s urging, Page had gone to see Bonzo play with Tim Rose at a club in north London. It was July 31, 1968 and, as Page says now, “He did this short, five-minute drum solo and that’s when I knew I’d found who I was looking for”.

As for Jones, a laconic, professorial figure, even in his early 20s, it wasn’t his style to go overboard about anything. He admits now, though: “I sensed something good might be going on with Jimmy.” He’d played on Yardbirds records before; worked with Page dozens of times. As he says: “Jimmy promised something a little different from a regular, one-style blues band.”

“I jumped at the chance to get him,” Page would recall. “Musically he’s the best of us all. He had a proper training and he has quite brilliant ideas.”

Page had previously considered Jack Bruce, on the brink of leaving an already disintegrating Cream; Ace Kefford, formerly of The Move, who had also recently auditioned for the Jeff Beck Group; even original Beck bassist Ronnie Wood.

“It was pretty obvious they’d probably make it, especially in America,” Wood says now. “But I wanted to get back to playing guitar and there was only ever going to be one guitarist in [Page’s] group.”

On Monday, August 19, the day before Plant’s 20th birthday, a rehearsal was arranged in a small room below a record shop in London’s Chinatown. “We ended up playing Train Kept A-Rollin’, which had been an old Yardbirds number,” recalled Jones. “We ran through it and I thought, is it just me or was that really good?” It wasn’t just Jonesy.

“It was unforgettable,” said Jimmy. “Everybody just freaked. It was like these four individuals, but this collective energy made this fifth element. And that was it. It was there immediately – a thunderbolt, a lightning flash – boosh! Everybody sort of went, ‘Wow’…”

The real test, however, would come out on the road, using a three-week tour of Scandinavia to trial-run a set list bolted together from old Yardbirds numbers and blues covers – stuff that would, as Page later told me, “allow us to stretch out within that framework. There were lots of areas which they used to call freeform but was just straight improvisation”. By the time the tour ended, “I’d already come up with such a mountain of riffs and ideas, because every night we went on there were new things happening”.

Twelve days after the tour, Page took his New Yardbirds into Olympic, a popular eight-track studio in Barnes, south London – the same studio the Stones had recently made Beggars Banquet in. Concentrating on simply laying down the live set they’d been hammering into shape augmented by a couple of extra tracks, starting with versions of the folk ballad, Babe I’m Gonna Leave You, and Willie Dixon’s You Shook Me,

“I wanted artistic control in a vice grip,” said Page. “Because I knew exactly what I wanted to do with these fellows.”

Nine days later, after a total of just 30 hours in the studio, the album had been fully recorded, mixed and was ready to be cut onto a mastered disc. Total cost, including artwork: £1,782.

Even taking into account how experienced and versatile session-vets like Page and Jones were – or the fact that all four had proved how well they gelled in the studio when performing as backing band [with Plant on harmonica] on a PJ Proby session in London, arranged for them by Jones, just prior to that first tour [the track Jim’s Blues, later released on the 1969 Proby album, Three Week Hero, is the first studio track to feature all four members of the future Led Zeppelin] – this was extremely fast work.

Opening with the rhythmic battering-ram that is Good Times Bad Times, as Chris Welch says, the immediate impression one got from hearing Led Zeppelin for the first time was one of pure shocking power, its opening salvo summing up everything the name Led Zeppelin would quickly come to represent. A pop song credited to Page, Jones and Bonham built on a zinging, catchy chorus, explosive drums and – at exactly the right moment – a flurry of spitting guitar notes, it pointed the way forward for rock music in the 70s, towards heavy-duty riffage and mallet-swinging drums.

Its counterpart, meanwhile, on side two, another Page-Jones-Bonham composition titled Communication Breakdown, with its spiky, downstroke guitar riff and grafting of the ostinato from Eddie Cochran’s Nervous Breakdown, was proto-punk; the sort of speeded up, one-chord gunshot the Ramones would turn into a career a decade later.

While Your Time Is Gonna Come, the third of the three originals on the album, is something else again: a wonderfully understated pop song built, in the fashion of the time, around a Bach fugue, played by Jones, then swept into a completely different musical zone by Page’s pedal steel guitar – an instrument he had literally picked up in the studio that day and begun to play.

The rest of the album, however, though equally impressive in the scope of its sonic architecture, was quite shamelessly unoriginal in its material, as exemplified by its final track, How Many More Times – also credited to Page, Jones and Bonham but a composition clearly based on several older tunes, primarily How Many More Years by Howlin’ Wolf, a number which Plant and Bonham had performed in Band of Joy, inserting snatches of Albert King’s The Hunter.

The ‘new’ Zeppelin version opened with a bass riff snatched from the Yardbirds’ earlier reworking of Smokestack Lightning, plus more than a passing nod to a mid-60s version of the same tune by Gary Farr and the T-Bones also re-titled How Many More Times [and produced by original Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky]. There was even a lick or two appropriated from Jimmy Rodgers’ Kisses Sweeter Than Wine as well as – bizarrely – a slowed-to-a-crawl take on Beck’s solo from the Yardbirds’ 1965 pre- Page hit Shapes Of Things.

All of which they might have gotten away with if so much else on the album didn’t also take its cue from the work of others, largely without acknowledgement. Indeed, of the other tracks on the album credited to various band members, all have subsequently had that contention challenged to varying degrees.

Beginning with Babe I’m Gonna Leave You, Page’s reworking of a traditional ballad first heard outside contemporary folk circles on a Joan Baez album, although not unjustly credited on the original pressings of Led Zeppelin as a ‘Traditional’ song, ‘arranged by Jimmy Page’, by the time of the 1990 release of the Remasters CD box set the credit had been amended to include A. Bredon, aka American folk singer Anne Bredon, who’d recorded her similar-sounding version over 15 years before.

Similarly, Black Mountain Side, an acoustic guitar instrumental in the exotic, modal style of Page’s earlier Yardbirds-era showcase, White Summer, down to the percussive accompaniment of the Indian tablas by Viram Jasani.

Where White Summer had been Page’s ‘interpretation’ of Davy Graham’s esoteric version of She Moved Through the Fair [or more accurately, Graham’s reinterpretation of the song as She Moved Through The Bizarre / Blue Ragga], with its unique DADGAD tuning – a signature Graham D-modal tuning devised for playing Moroccan music that also proved especially efficacious for ancient modal Irish tunes – Black Mountain Side was in fact Page’s instrumental version of fellow Graham disciple Bert Jansch’s 1966 recording of another traditional Gaelic folk tune titled Black Water Side – originally shown to Jansch by Anne Briggs, another Page favourite who had herself been shown the tune by an old folklorist named Bert Lloyd.

As a result, although Jansch’s then record company Transatlantic sought legal advice, in consultation with two eminent musicologists and John Mummery QC – one of the most prominent copyright barristers in the UK at the time – it was decided not to pursue an action for royalties against Page and/ or Led Zeppelin.

As head of Transatlantic, Nat Joseph explained, “It had been reasonably established that there was every chance that Jimmy Page had heard Bert play the piece. However, what could not be proved was that Bert’s recording in itself constituted Bert’s own copyright, because the basic melody, of course, was traditional.”

Nevertheless, crediting Black Mountain Side solely to Page seemed a bit rich. Certainly to Jansch himself, who told me, “The thing I’ve noticed about Jimmy whenever we meet now is that he can never look me in the eye. Well, he ripped me off, didn’t he?” He smiled. “Or let’s just say he learned from me. I wouldn’t want to sound impolite.”

But then, as Page himself admitted, “At one point, I was absolutely obsessed with Bert Jansch. When I first heard [his 1965 debut] album I couldn’t believe it. It was so far ahead of what anyone else was doing. No one in America could touch that.”

Clearly, he was even more taken with Jansch’s third album, Jack Orion, which contained not only Black Water Side but was full of the sort of sinister drones and fierce, stabbing guitar that Page would incorporate into his work throughout his subsequent career in both The Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin.

Even the two acknowledged covers on the Zeppelin album – I Can’t Quit You Baby and You Shook Me – drew accusations of plagiarism. Not through lack of credit this time – both tracks were originally by Willie Dixon, and are credited as such on the sleeve – but, in the case of the latter, that it was a rip-off of the version recently released on the Beck Group’s Truth.

Taken from the same Muddy Waters EP that both Page and Beck had listened to as boyhood friends [the same EP, coincidentally, that contained the track You Need Love which would provide Page with yet more ‘inspiration’ when it came to the second Zeppelin album], Jimmy has always claimed it was simply “a coincidence” the same song ended up on both albums; that he hadn’t realised Beck had already recorded a version for Truth – even though Zep manager Peter Grant [then also working for Beck] had given him an advance copy weeks before its release.

Even if it were possible that Page had somehow neglected to afford the album even a cursory spin, it seems inconceivable that John Paul Jones would not have mentioned that he had played Hammond organ on the Truth version. The first Jeff Beck knew of his friend Jimmy’s decision to record the same track with his new group was when he played it to him.

According to Beck, “My heart just sank when I heard You Shook Me. I looked at him and said: ‘Jim, what?’, and the tears were coming out with anger. I thought ‘This is a piss-take, it’s got to be’. I mean, there’s Truth till spinning on everybody’s turntable, and this turkey’s come out with another version.”

Years later, Page shrugged when I mentioned it. Beck, he insisted, “was attempting an entirely different thing”. And, in fairness, listening to both tracks now, four decades on, what is most striking is the lack of similarity between the two tracks. While the Beck version is short and gimmicky, the Zeppelin version is almost three times as long, portentous, with swampy bottleneck guitar more redolent of the original’s swooning rhythms, while Page’s guitar solo is fluid, haunting and mysterious, not bitty or showy like Beck’s. It’s then the thought occurs: Page knew exactly what he was doing. Of course he’d heard the Beck version. This was his hefty riposte. That when he played it to Beck he was saying: there you go, Jeff, that’s how you do that one. Then probably regretted it when he saw how badly his old friend took it. But if Page wanted to show he was better than Beck by beating him at his own game, it conversely had the opposite effect, making critics feel he was inferior. A feeling that persists in highbrow musical circles to this day.

The most blatant steal on the first Zeppelin album, though, occurred on the track ironically destined to become one of the most closely associated with Jimmy Page: Dazed And Confused. Although credited solely to Page, the original version of the song had been written by a 28-year-old singer-songwriter named Jake Holmes. Holmes had already tried his hand at various branches of the entertainment industry – from comedy to concept albums – by the time he and his two-man acoustic backing band opened for The Yardbirds at the Village Theater in New York’s Greenwich Village in August 1967.

His solo album, The Above Ground Sound Of Jake Holmes, had been released that summer. Included from it in his set was a witchy ballad entitled Dazed and Confused. Although acoustic, it included all the signature sounds The Yardbirds – and later Zeppelin – would appropriate into their versions, including the walking bass line, the eerie atmosphere and the paranoid lyrics: not about a bad acid trip as has long been suggested, says Holmes now, but a real-life love affair that had gone wrong.

Watching him perform the song spellbound from the side of the stage that night in 1967 were Yardbirds drummer Jim McCarty and Jimmy Page. McCarty recalls he and Page going out the next day and buying a copy of the Holmes album specifically to hear Dazed And Confused again. Given a new, amped-up arrangement by Page and McCarty, with lyrics only slightly altered by singer Keith Relf, it quickly became a highlight of the Yardbirds’ live show.

Never recorded except for a John Peel session for Radio 1 in March 1968 – a version which sounds almost identical musically to the number Page would take full credit for on the first Zeppelin album, but which on the expanded 2003 remastered CD version of the Yardbirds’ Little Games album is credited to: ‘Jake Holmes, arranged by the Yardbirds’ – there was never any question in the rest of the band’s minds over who the song had been written by.

“I was struck by the atmosphere of Dazed And Confused,” said McCarty, “and we decided to do a version. We worked it out together with Jimmy contributing the guitar riffs in the middle.”

The only substantial change Page made from the version he’d been performing with The Yardbirds just three months before was his own rewrite of the lyrics, including such darkly misogynistic ruminations as the “soul of a woman” being “created below”. Other than that, the song stuck to the original arrangement, up to the bridge, where even then the fret- tapping harked back to Holmes’ original.

The only other difference of note were the effects Page obtained from sawing a violin bow across the E string on his guitar, creating a startlingly eerie melody full of strange whooping and groaning noises; another trick from his sessions’ days.

As if to prove just how indiscriminate he was in his ‘borrowing’, Page followed up the bowing section of Dazed… with a series of juddering guitar notes lifted wholesale from an obscure Yardbirds’ B-side called Think About It, as happy to be recycling his own ideas as everyone else’s.

“I didn’t think it was that special,” says Jake Holmes now. “But it went over really well, it was our set closer. The kids loved it – as did The Yardbirds, I guess.”

He says it wasn’t until “way later” he first became aware that Page had recorded his own version with Zeppelin – and given it his own songwriting credit. His initial reaction was to be blasé.

“I didn’t give a shit. At that time I didn’t think there was a law about intent. I thought it had to do with the old Tin Pan Alley law that you had to have four bars of exactly the same melody, and that if somebody had taken a riff and changed it just slightly or changed the lyrics that you couldn’t sue them. That turned out to be totally misguided.”

Over the years, he says, he has “been trying to do something about it. But I’ve never been able to find [a legal representative] to really push it as hard as it could be pushed. And economically I didn’t want to be spending hundreds and thousands of dollars to come up with something that may not work. I’m not starving, and I have a lot of cachet with my kids because all the kids in their school say, ‘Your dad wrote Dazed And Confused? Awesome!’. So I’m a cult hero.”

In terms of royalties, he just wants “a fair deal. I don’t want [Page] to give me full credit for this song. He took it and put it in a direction that I would never have taken it, and it became very successful. So why should I complain? But give me at least half-credit on it.”

The fact that Dazed And Confused was destined to become one of Led Zeppelin’s great set-piece moments, he astutely points out, “is partly the problem… For [Jimmy Page], it’s probably more difficult to wrench that song away from him than it would be any other song. And I have tried, you know. I’ve written letters saying, ‘Jesus, man, you don’t have to give it all to me. Keep half! Keep two-thirds! Just give me credit for having originated it’. That’s the sad part about it. I don’t even think it has to do with money. It’s not like he needs it. It totally has to do with how intimately he’s been connected to it over all these years. He doesn’t want people to know.”

Over the years, Page and Zeppelin’s appropriation of other artists’ material was to become a longstanding criticism. Rightly so, one might argue, when one considers just how many times they would be accused of it throughout their career. And yet, they are hardly the only guilty ones.

David Bowie ripped-off the Rolling Stones for Rebel Rebel; the Stones ripped-off Bo Diddley for Not Fade Away. And let’s not even start on the bands that have subsequently ripped-off Zeppelin. It was also partly the era.

The Yardbirds were equally guilty. Tracks like Drinking Muddy Water – attributed to Dreja, McCarty, Page and Relf – was an obvious rewrite of the Muddy Waters’ tune Rolling And Tumbling. But then Waters’ version was itself a patchwork of several earlier blues numbers. The same went for the aptly titled Stealing, Stealing, a song originally by Will Shade’s Memphis Jug Band, but with The Yardbirds again listed as authors.

One could argue that with the folk and blues traditions based almost entirely on tunes handed down over generations, each passing bringing it’s own unique interpretation, that Page and others are as within their rights to claim authorship of their own interpretations of this material as Muddy Waters, Davy Graham, Willie Dixon, Bert Jansch, Blind Willie Johnson, Robert Johnson and all the other artists Led Zeppelin would knowingly ‘borrow’ from over the years.

In the early part of the 20th century, the legendary ‘patriarch’ of American country music, A.P. Carter, copyrighted dozens of songs written decades before his arrival in the Appalachians, many of which had their origins in ancient Celtic tunes from the British Isles. As a result, to this day a venerable old masterpiece like Will The Circle Be Unbroken is still spuriously credited to Carter.

Similarly, Bob Dylan – widely considered the most groundbreaking and original songwriter of the late 20th century – described his own debut album as “some stuff I’ve written, some stuff I’ve discovered, some stuff I stole”. He was talking mainly about arrangements, such as his Man Of Constant Sorrow, lifted wholesale from Judy Collins’ Maid Of Constant Sorrow. Or, most brazenly, the steal of Dave Van Ronk’s innovative arrangement of House Of The Rising Sun, which Van Ronk resented hugely.

Later on, Masters Of War would be sung to the tune of Nottamun Town; Girl From The North Country from Scarborough Fair; Blowin’ In The Wind from an old anti-slavery song, No More Auction Block; Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right from a traditional Appalachian tune, Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I’m Gone. None of which ever received any due credit on Dylan’s album sleeves. John Lennon believed Dylan’s 4th Time Around to be a deliberate parody of his Norwegian Wood. But then what was All You Need Is Love if not Lennon’s ‘re-reading’ of Three Blind Mice?

Jeff Beck was at it too, now admitting that Truth included more than one outright steal, including the track Let Me Love You – credited on the sleeve to one Jeffrey Rod [i.e. Beck and his then vocalist Rod Stewart] – based on an earlier Buddy Guy track of almost the same name.

“We just slowed it down and funked it up a little with a Motown-style tambourine,” Beck reveals in the sleeve notes for the 2005 remastered CD version of Truth. “There was a lot of conniving going on back then: change the rhythm, change the angle and it’s yours. We got paid peanuts for what we were doing and I couldn’t give a shit about anybody else.”

Other Jeffrey Rod compositions included Rock My Plimsoul [BB King’s Rock Me Baby]; Blues De Luxe [BB King’s Gambler’s Blues]; and I’ve Been Drinking [from the Dinah Washington original Drinking Again].

Page has also subsequently acknowledged the origins of some of the material he repurposed for Zeppelin.

“The thing is they were traditional lyrics, and they went back far before a lot of people that one related them to. The riffs we did were totally different, also, from the ones that had come before, apart from something like You Shook Me and I Can’t Quit You, which were attributed to Willie Dixon.”

More to the point, he says: “I’m only the product of my influences. The fact that I listened to so many styles of music has a lot to do with the way I play. Which I think set me apart from so many other guitarists of that time.”

Nevertheless, the accusations of plagiarism would have a debilitating effect on Zeppelin’s long-term credibility. It’s one thing to ‘assimilate’ old songs, quite another to claim credit for having built them from the bottom up. Even today when sampling is the norm in the hip-hop world, woe betide any artist that omits to credit original sources.

On a purely musical level then, while Page has often told me how, for him, the first Zeppelin album “had so many firsts on it, as far as the content goes”, in fact the first Zeppelin album was less a new beginning for Page than a culmination of everything that had gone before. All it really proved was that Zeppelin were great ‘synthesisers’ of existing ideas. That this was accomplished in an era when such notions were still considered outside acceptable bounds says something about fortune and the talent to influence it.

With Jimmy Page at the helm, Led Zeppelin would have both. In fact, the real innovations of that first album were in the advanced production techniques Page was able to bring to bear and the sheer weight of musicianship he had assembled to execute them.

Being able to produce such power and cohesiveness from a line-up that was barely a month old at the time the album was recorded was extremely impressive; to capture that energy on record, however, little short of astonishing; his previously unknown talent as a producer overshadowing even his dexterity as a guitar player. Not least in his innovative use of backwards echo – an effect that engineer Glyn Johns told him couldn’t be done until Page showed him how – and what Jimmy calls “the science of close-mic’ing amps”. That is, not just hanging microphones in front of the band in the studio, as was the norm at the time, but draping them at the back as well, or floating them several feet above the drums, allowing the sound to “breathe”.

Or taking the drummer out of the little booth they were routinely shoved into in those days and allowing him to play along with the rest of the band in the main room. This would lead to a lot of ‘bleeding’ – the sound of one track seeping into another, particularly when it came to the vocals – but Page was happy to leave that in, treating it as “one more effect” that gave the recording “great atmosphere, which is what I was after more than a sterile sort of sound”.

As Robert Plant later put it, listening to what Page had done on the first Zeppelin album “was the first time that headphones meant anything to me. What I heard coming back to me over the cans while I was singing was better than the finest chick in all the land. It had so much weight, so much power…”.

The core material may have been derivative, the ‘light and shade’ aspect not nearly so interesting or new as Page still insists – certainly not compared to the multifaceted aspects of the music then being made by The Beatles and the Stones, or even Dylan and The Who, all of whom had alternated between electric and acoustic instrumentation for years, playing not just with light and shade but helping shape the parameters of rock music as a creative genre – but it had never been done with such finesse and know-how, or quite so much determination to succeed at any cost.

Indeed, the first Zeppelin album was an almost cynical attempt to outdo its immediate competitors – Hendrix, Clapton, Townshend, and of course the unwitting Beck – while at the same time demonstrating that the man at the back, lurking in the shadows – Page himself – had more up his sleeve than mere conjuring tricks.

That this was a rock visionary with incredible mastery over his tools, a musical sorcerer who had stood off to one side watching for long enough. Now it was time to do, to be, to overcome. And if anyone was going to get credit for that tremendous achievement, it was Jimmy Page.

When Glyn Johns – who’d also worked with The Beatles, the Stones and The Who, and who Page had known since his days as a teenager playing in a local hall in Epsom – asked for a producer’s co-credit on Led Zeppelin, Page gave him short shrift. “I said, ‘No way. I put this band together, I brought them in and directed the whole recording process, I got my own guitar sound – I’ll tell you, you haven’t got a hope in hell’.” Nor anyone else that would come along.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 131.