The indie vs rock battle at the heart of the Manic Street Preachers' Generation Terrorists

They said they’d make one album, sell 16 million copies and split up. What really happened was far more dramatic. Inside the unique cultural, musical and political forces that made the Manics the smartest band of the 90s

"It's heavy metal, cock-rock shit!" It's the summer of 1987 and the Manic Street Preachers are in James Dean Bradfield's bedroom discussing the future direction of the band. James's guitar playing is the cause of much concern. It's just getting too fucking good.

"James was accelerating as a guitarist so quickly," remembers Nicky Wire, "considering he didn't pick up a guitar till he was 14, 15. He was obviously spending all his time sitting around noodling."

And the result of all that noodling was a feeling that the band's music was starting to suffer – it was suddenly full of solos, riffs, twiddly bits.

"I stayed in all that summer and learned how to play Appetite For Destruction from start to finish," remembers James, "and it was getting on Sean's nerves. We were living together in my parents' house and he could see me going more and more in one direction. Now I wasn't just playing a couple of Rush licks quite badly, I was playing a whole album quite well. Our songs started going in a heavier direction…"

James's cousin, drummer Sean Moore, was concerned. He didn't get into a band to play heavy fuckin' metal. The two cousins have boiled the argument down to the simple question that has faced – ooh – probably no other band in the history of music: "Are we gonna be Guns N' Roses or are we gonna be McCarthy?"

These days, McCarthy are all but forgotten. The Manics remain their biggest cheerleaders, covering several of their songs and talking up their debut album I Am A Wallet whenever possible. A uniquely 80s band, McCarthy were a Marxist indie-pop group (from Essex!) whose iron-fist-in-a-velvet-glove approach saw them grease lyrics about kiddie-fiddling MPs and beheading Prince Charles with sweet melodies and chiming guitars.

Although both bands were angry, anti-establishment and punk-influenced, musically McCarthy were about as far from GN'R as it's possible to get: rock without the riffs and solos, without the denim and leather machismo, the blues screeching or the foot-on-the-monitor showboating. If the choice facing the Manics seems like a no-brainer now (follow the band behind the biggest-selling debut album of all time or a bunch of indie obscurists), it needs some context: McCarthy and the generation of psychedelic punk bands that they were a part of – including a fledgling Stone Roses and Primal Scream – were flavour of the month in the pages of the NME.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Do they shoot for the moon or lower their sights a little? Make the grand play for hearts and minds or settle for credibility and cult status? The argument rages. Richey Edwards and Nicky Wire, later to become the band's mouthpieces, sprawl across a bed and keep out of it. ("Nicky and Richey were just giggling, watching the two proles going at it," says James.)

"Me and James were on the Guns side," remembers Wire. "I think Richey was kinda ambivalent, Sean was definitely on the McCarthy side. Echo & The Bunnymen had been his favourite band so he was much more astute. We all thought the McCarthy album was one of the greatest albums ever, but my view was that to get over the barrier – coming from Wales, looking like we did – I always thought cartoonish was quite good. The Pistols, Ramones, [San Francisco riot grrrls] Fabulous Disaster. People were gonna laugh at us anyway so I thought: 'If they're gonna laugh at us, let's be larger than life.'"

People were gonna laugh at us anyway so I thought: 'If they're gonna laugh at us, let's be larger than life.'

Nicky Wire

Nicky was well acquainted with 'larger than life'. He'd been brought up on "everything from Rush to UFO. Whitesnake were my favourite band. I had the denim jacket with the Ready An' Willing cover painted on. Once they went to America and re-recorded Here I Go Again I went off them, but the original and Fool For Your Loving... Trouble is a really brilliant-sounding album. I love Trouble."

"Nicky was a proper metalhead when he was young," says James. "He was dead into Rainbow, he was even into stuff like Spider. Richey was dead into his Hanoi Rocks. [As the lyric writers] I think they liked the idea of this big, bold carriage rumbling along carrying their message. Whereas Sean took quite a bit of umbrage."

Drummer Sean – co-writer of the music with James – was distressed to see this hard-rock influence seeping into his band's music.

"Richey was in the same year as me. In our music lessons we'd bring in stuff like The Fall’s Perverted By Language," he says. "Then he discovered all of the heavy metal stuff so [over the years] Skid Row, Pantera and that sort of thing crept its way in. Richey was listening to Dogs D'Amour when we were in the studio doing Generation Terrorists. I think he liked the story behind it more than the music sometimes."

The McCarthy-versus-Guns argument was, says Wire, the pivotal moment in the band's genesis: "We were starting to write songs like You Love Us and Born To End – all before we'd signed to Sony – and they were just rock songs really."

"Songs got heavier," says James, "and even though I was still a massive McCarthy fan, of the two angels on my shoulder, GN'R won."

It made sense. McCarthy were fey, gentle, asexual. The Manics were from Blackwood, South Wales. Post-industrial. Small-town. Proud. Brutal. What-the-fuck-you-lookin'-at-bud.

"I was like, 'Aw c'mon, we're from Wales'," says Bradfield. '"We come from working-class environments – our physicality has got to be represented.'"

The argument continued "for hours and hours and hours" reckons Wire. In the end, James got so frustrated that he took his original copy of Appetite and smashed it to bits.

"There you are!" he said. "Fuck it! That's the end of that..."

"But y'know," says Sean, "then he went out and bought another copy a couple of weeks later."

Because it wasn't the end, of course. It was just the beginning.

Manic Street Preachers were the most contrary band in rock'n'roll. A fiercely intelligent band in love with big, dumb rock that merged the lyrical smarts of Morrissey and McCarthy with the guitars of Michael Schenker and Slash. A band that fed off anger, that needled their audience just as they taunted their haters with a song called You Love Us.

A band that would quote Rimbaud, Larkin and Plath and yet tell the indier-than-thou NME that their hero of 1991 was "Sebastian Bach for Monkey Business and Wasted Life".

Armed with a song that could finally see them cross over into Kerrang! territory, they made a homoerotic video, despite the fact that none of them were gay. Appearing at Glastonbury, Nicky Wire told the beatific throng: "Let’s build some more fucking bypasses over this shithole:"

I grew up in the fucking valleys. Antagonism is just foreplay.

James Dean Bradfield

On stage in New York, he quipped, "The only good thing about America is that you killed John Lennon."

Where most bands seek adulation, the Manics sought confrontation. "We've never been about making friends, really," says Sean. "Even at 44, there's still an element where I just want to really tear it up, smash it."

James shrugs it off: "I grew up in the fucking valleys," he says. "Antagonism is just foreplay."

Nicky Wire, the source of much of the aggro, is more contrite: "You know when people look back at their younger selves and go, 'I don't regret anything, I have no regrets'? I just have tons of them.

“I remember myself vividly and – I loved my home life, my mum and dad were brilliant, I was never in any trouble – but as soon as I got in the band, I used to fucking endlessly talk like a cunt all the time. It's still in me now. I've not changed, it's only because I control it."

And when they weren't upsetting people, Nicky and Richey were astounding them (and scaring the living shit out of James) with a string of outlandish claims:

"In a year's time we'll be headlining Wembley... "

"We're going to make an album better than Never Mind The Bollocks.. "

"We're going to write one double album, sell 16 million copies, and then split up."

"There's no glory in being top of the indie charts, there's no glory in being Top 30. You've gotta be No. 1. We just wanna be the most important reference point of the 90s. That's all."

Oh, is that all?

A year later, they didn't headline Wembley, they played Northampton Roadmenders. Generation Terrorists didn't have the cultural impact of Never Mind The Bollocks, go No.1, or sell 16 million copies and the Manic Street Preachers did not split up.

And the talking heads on those dumb I ❤️ The 90s shows probably won’t remember them as the most important reference point of the 90s. But that’s their loss, because the Manics were a unique collision of cultural, musical and political forces that made them one of the most fiercely intelligent, musically informed and thrilling bands of the decade.

"We were a strange bunch of birds," admits James. "My first love was ELO, and then I became a proper indie kid for a while with bands like Big Flame, Jasmine Minks, The Bodines. Then it was The Clash, Magazine, Wire, Pistols, Skids, and then I suddenly woke up and there was Guns N' Roses and Public Enemy at the same time."

Sean remembers James's roots differently: "We met Paul McCartney once," he chuckles, "and James said to him, 'I love Pipes Of Peace...' You could see McCartney sort of cringe, thinking, 'Oh God! Probably my worst album ever.' You know, The Frog Chorus and all that.

“James bought Elton John records and Billy Joel and all that sorts of stuff. Diana Ross, Motown. Bizarrely, for me it was more jazz: Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and then it was indie, 'alternative' music really."

Music, literature and films were all part of their great escape. They swapped books, obsessed over movies, were blown away by the 10th anniversary of punk celebrations on TV and in the music press, and found perhaps unlikely role models in Guns N' Roses and Public Enemy.

"I remember hearing the lyrics to Welcome To The Jungle," says James, "and thinking, 'This isn't like hair metal. This is proper rock and roll. They haven't forgotten about punk, they haven't forgotten about the Stones - this is what rock'n'roll should be.' It wasn't [Warrant's] Cherry Pie. It was completely disaffected, nihilistic.

“And then I remember hearing Bring The Noise by Public Enemy and thinking, 'That's how l feel.' Forgetting all the stuff about Louis Farrakhan [the black American Muslim separatist leader], the essential message is basically about someone who's been bored all of his life and now it's his fucking time.

“We thought that [PE's] It Takes A Nation Of Millions and Appetite were one and the same record in a strange way, even though they were poles apart. It just seemed like their time. Like, 'Fuck me, something's happening!"'

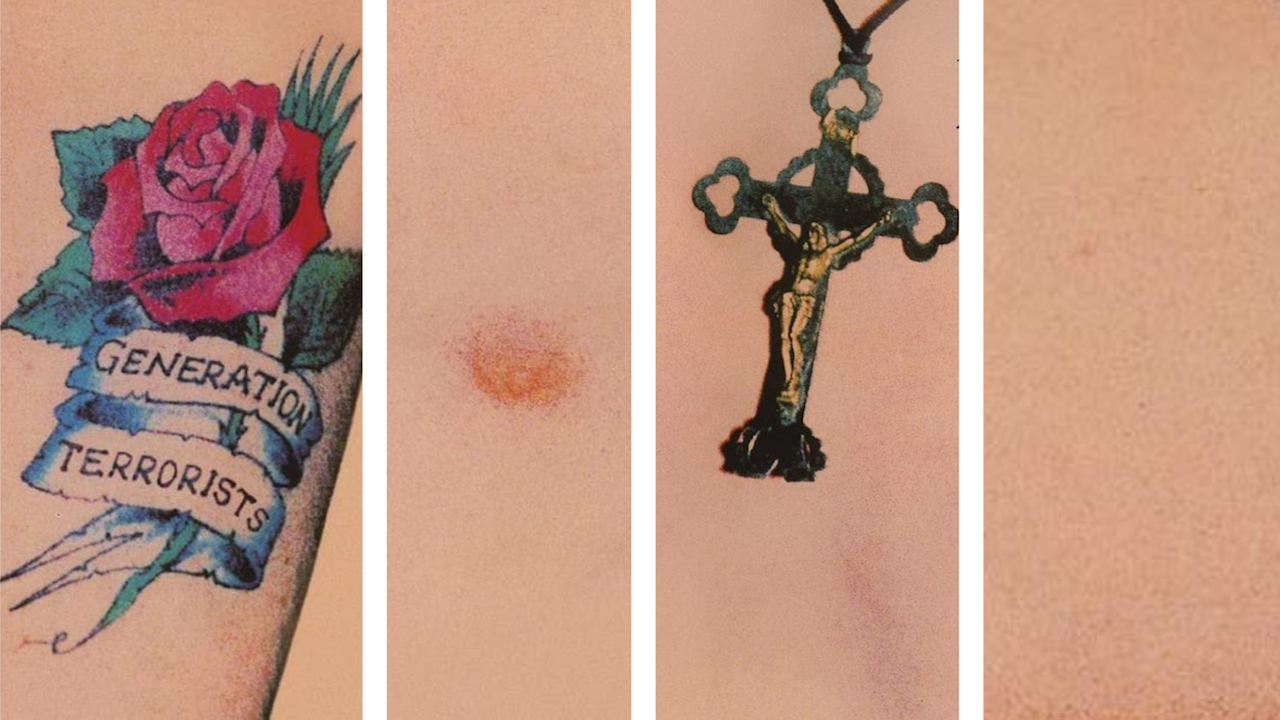

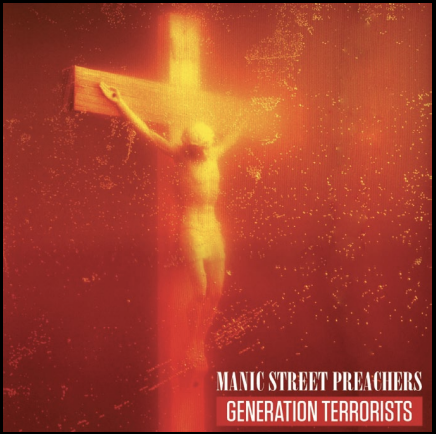

The original sleeve idea for Generation Terrorists was to use Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, a photograph of a crucifix in a jar of the artist’s urine. Could GT have sold millions if it’d been pared down to a single album packaged in that sleeve: leaner and meaner, more Alice In Chains than Skid Row?

“That definitely should have been the cover,” says Moore. “But we were signed to a major and we understood that we couldn’t do absolutely everything that was in our heads.”

“We did miss out on the art-rock side with some of the production and the artwork,” admits Bradfield. “One of the initial ideas from the record company was an Exocet landing through a stage. So that panicked us a bit. [With the sleeve] I think Richey just ran out of time. It’s got a sort of soft focus, homoerotic, soft metal chic about it. I kinda like it. But, yeah, Piss Christ would have re-framed it.”

As a single album, modelled on Appetite For Destruction’s running time of 53.44, GT could have run: Slash ‘n’ Burn, Nat West-BarclaysMidlands-Lloyds, Born To End, Motorcycle Emptiness, You Love Us, Love’s Sweet Exile, Little Baby Nothing, Stay Beautiful, Repeat, Spectator Of Suicide (Heavenly version), Methadone Pretty, Condemned To Rock ‘N’ Roll. Could it then have sold Appetite-size numbers?

“Er, no,” says James.

Outside of London, the music press's influence had waned. Goths, punks, psychobillies, bikers and indie kids rubbed shoulders at 'alternative discos' where the DJ would play The Clash followed by AC/DC, the Cramps, Hanoi Rocks and the Sisters Of Mercy, and the dance floor was a mess of chicken dancing, headbanging, crimped hair and patchouli oil.

After years of Thatcher, the miners' strike and unemployment, the NME expected us to get excited about people in cardigans and duffle-coats acting like children (C86), while Kerrang! got a boner about processed party metal? Yeah, right.

"We felt like we were living in a vacuum," says James. "Everything that we'd been told was great about where we were from had been destroyed economically, culturally. So you start looking for other things, in this barren wasteland of the 80s, and music was the obvious choice. Because, number one, it seemed completely alien to the surroundings you'd grown up in.

"I think journalism has always undersold the futuristic angle of guitar music. Whether it be Rush, early Guns, The Clash or Magazine, I don't think journalism has actually captured the displacing quality of what guitar music actually was at that time in our lives. It didn't sound like anything else that we'd ever experienced. It actually seemed like something that had arrived fully formed from the future and was amazing to us. People might laugh at that now, but it was something that actually jolted you, woke you up and gave you new purpose."

The Manics transformed their lives through sheer willpower. In 1990 Richey sent a copy of New Art Riot, their shambolic four-track debut, to Philip Hall, the head of PR company Hall Or Nothing, and convinced him to drive to Wales to check them out. In person they talked such a good fight that he offered to manage them. (Note to cynics: yes, they were managed by a PR man.)

They got signed to Heavenly Records, then at the forefront of the indie-dance crossover, with records by Flowered Up and Saint Etienne behind them. They appeared in the music press with badly stencilled shirts and bowl cuts and got sneered at, as they knew they would. Motown Junk, a four-minute explosion of last-gang-in-town riffs and iconoclastic lyrics (“I laughed when Lennon got shot”) pricked the ears of the great unwashed across the country, but still saw them dismissed as Clash revivalists.

At the height of music press antipathy, they released a delicious ‘fuck you' of a song called You Love Us that sounded like Guns N' Roses gleefully taking a hammer to the Stooges' I Feel Alright.

“We are not your sinners,” sang James. “Our voices are for real.” Shortly afterwards, Richey – exasperated at NME writer Steve Lamacq's refusal to take them any more seriously than New Wave Of New Wave flash-in-the-pans like Birdland or These Animal Men – carved the phrase '4 REAL' on his arm with a razor blade mid-interview. Suddenly the Manics didn't seem quite so laughable.

(Apart from maybe in Wales: "Where we come from," Nicky said shortly afterwards, "people spill out of the pub, kick the shit out of each other, smash up their estate, then beat their wife or girlfriend. So, when people back home heard about Richey, they were laughing their heads off.”)

With column inches, if not hit singles, under their belt, they signed to Columbia and were paired up with producer Steve Brown. The man who took The Cult from goth-rock obscurity and into the charts with the Love album, and produced The Godfathers' underrated 1988 bruiser Birth School Work Death, he set about remodelling the band in the image they'd chosen – Guns N' Roses-meets-McCarthy – with an album that, even if it didn't sell 16 million records, at least backed up the bravado.

"To us, She Sells Sanctuary was a brilliant rock record," says Nicky. "That's one of the main reasons we worked with Browny. And once we went with him we were on a pattern – that's what the record was gonna sound like."

The single Stay Beautiful signalled the step up. Tasked by Brown to write a great song that they could imagine being played on radio – ie, without any swearing on it – they delivered a demo of a punk-metal anthem with the chorus, 'Why don't you just fuck off!”

With consummate professionalism, Brown worked on the song with the band, then, at the last minute, edited out the ‘fuck off’, replacing it with a squealing guitar lick. The band admired his chutzpah. It worked live too, where the audience supplied the fuck off. The single went Top 40.

Brown, says Bradfield, had "really good management, good people skills" and knew how to get the best from his charges. "He just kept giving us this clue that there was something there and we should hunt it down," says James.

For album opener Slash 'N' Burn, for example, he took what was "a shambling indie rock song" and bullworked it into a ripped, riff-driven rocker.

James: "He was like, ‘No, it's got to have straight lines, it's got to be violent! It's got to have violence and grace!' That was his thing: violence and grace. He made me write that middle section – that Michael Schenker bit. And because he produced Love, we just implicitly trusted him."

Primal Scream had taken the rock-dance crossover into the charts with Loaded in March 1990. The Manics were out of step with prevailing fashions but fiercely competitive. "We were looking at Creation Records and Primal Scream and all those bands that were starting to get into the Top 40," says Sean. "Working with Steve was an opportunity to hopefully appear on Top Of The Pops. It was time to move up a level. We'd signed to Columbia, Sony, so it really was, 'This is the big time now.'"

Brown's ethos was simple: you've got to be able to fuck to it, dance to it and drive to it. Suddenly, says Sean, making music became about "drum machines and the close editing of tracks – creating this perfect pop song for radio".

As the drummer, he had a steep learning curve ahead: after spending a whole week trying to get a hi-hat sound on the song Crucifix Kiss, they realised that recording the band live wasn't going to work.

"Steve Brown had this almost Mutt Lange, Def Leppard approach to things,” says Sean. “We had a few sessions with a drum programmer and I sort of looked at that, going, 'Ooh, things are starting to slip away'." Instead of throwing his sticks across the room, Sean sat behind the guy for a session and asked questions. "And then I went out and bought all the kit and sat down for a weekend and learnt how to do it. And didn't look back."

With the musicians pushed to the limits of their abilities, Wire and Edwards hunkered down to write words to justify the big claims and the acres of column inches they had gathered over the past two years. People still expected the Manics to burn out like S*M*A*S*H, a New Wave Of New Wave band who had similarly ruffled feathers with single (I Want To) Kill Somebody (“I wanna kill somebody/ Margaret Thatcher, Jeffrey Archer/Michael Heseltine, John Major/ Virginia Bottomley especially…”) or turn into a polished glam-punk pop band a la Transvision Vamp, another band covered in leopard-skin and lipstick, with a similar Marilyn Monroe/Betty Blue obsession.

"We were really young," says Nicky, "so sometimes it comes across slightly like an Athena postcard or something. But one thing we really thought we had over everyone else, Richey in particular, was our intelligence. We had our degrees and we were fiercely working class and, I'm not saying we thought we were superior, we just thought we could hold our own with anyone."

Little Baby Nothing turned an E Street Band arrangement into a staunchly feminist anthem (“Used, used, used by men”). In a great piece of out-of-the-box thinking, they were joined by ex-porn star Traci Lords, who had recently revealed that many of her movies had been made while she was underage.

The song became like a Bat Out Of Hell duet re-written by Valerie Solanas: “You are pure, you are snow/We are the useless sluts that they mould/ Rock'n'roll is our epiphany/Culture, alienation, boredom and despair.”

If Nat West-Barclays-Midlands-Lloyds grated a little in 1992, it now seems way ahead of its time. In ‘92, banks seemed boring and corporate – by 2008, it was clear they were our enemies. "We were writing in slogans and some of the slogans pay off: Nat West-Barclays-Midlands-Lloyds is as prophetic as you can fucking get. There's a brilliant Richey line, where he goes, ‘Black horse apocalypse, death sanitised through credit.' He just fucking nails everything in two lines."

James had to turn these words into something with rhythm and melody, as well as be the mouthpiece for Richey and Nicky, whether they wrote in support of capital punishment (as they did on The Holy Bible's Archives Of Pain) or penned lines like, “I wish I had been born a girl/Instead of what I am… This mess of a man” (This Is My Truth...'s Born A Girl).

"I can only think of two other proper bands where it's the same: Rush and The Who," says James. "I had a tiny bit of a complex about it at the start – but only if there was something in a lyric and I had to ask what it was. But I got over it because it became the most beautiful homework in the world. And it became a part of my process where I would never be able to write music unless I had the lyrics in front of me. thought, 'If I'm not writing the lyrics then I have to show them as much respect as possible'."

In September, the band took time out to buy Use Your Illusion when it went on sale at midnight on the 16th. The week before, a single called Smells Like Teen Spirit had been released. "And that's when we just went, 'Oh fuck it, we've had it now,'" laughs Sean. "Nah, we always felt that we were outsiders anyway. It was just like, 'Oh well, we'll just stick to our guns and see what happens."'

They didn't realise it at this point, but they had an ace up their sleeves: a song so epic, elegiac and graceful that it would silence the doubters and make even the faithful do a double-take. That the seeds of Motorcycle Emptiness lay in two separate and unremarkable songs, one a sub-Talulah Gosh slice of twee pop called Go Buzz Baby Go, is like discovering that Kashmir was written by John Otway.

"I remember Steve Brown saying, 'This is going to be brilliant, but you need to have a middle section and you need a guitar solo,"' says James. "So I stole a middle section from a song called Behave Yourself Baby and then did a guitar solo."

Still, it wasn't gelling. "[Brown] kept pulling the track back up and saying, 'There's something missing...' Then one day I came down like, 'I was thinking maybe I could put this riff on it,' and he was like, 'Baby, that's brilliant! You need a riff! You need a riff that identifies you – you need your Sweet Child O' Mine!'

"If Steve hadn't have kept pushing us on Motorcycle, I don't think it would have become the song it was," says James. "He just kept pushing us to write parts, to atomise everything into one song. He was trying to tell us that we had to atomise all the outrageous statements that we'd made, and all our ambitions. We had to atomise it in one song, completely and utterly, if people were going to remain convinced by all of our bullshit and bluster. And if he hadn't, we might not have survived."

Released in June 1992, Motorcycle Emptiness was the album's last single. It went to No.17 in the UK singles chart, one place lower than You Love Us. But it symbolised something greater, something that was way beyond the reach of These Animal Men.

Generation Terrorists isn't the band's greatest album – it's overlong and inconsistent – but it was still a triumph. Some trad-rockers prefer it to The Holy Bible, the band's more celebrated but too-intense-for-some third album, and you can see why: for all the lyrical desolation and useless-generation finger-pointing, the Manics' debut was jubilant and celebratory, the sound of a band realising that it had a future.

"It never really clicked on an entire album until The Holy Bible," says James. "With GT there was a bit of grand folly in there, definitely, overarching ambition. But it kind of paid off on some of the songs. On others you can hear the seams ripping a bit. It's a band gestating and really trying to get there. And I love it for that.

“I love the naivety of it. You don't get that fierce idealism without being naive. Because you can never be fiercely idealistic unless you completely believe in what you're doing. And you can't completely believe in what you're doing unless you're misguided," he laughs and then gets serious: "You can’t. You can’t, can you?'

Generation Terrorists went to No. 13 in the UK album chart. It didn't sell the 16 million copies they were aiming for but by that point no one really cared. Well, except the band. "To make a statement like that and know you're going to fail by your own standards is fucked up," says James. "And to not be part of that decision is quite strange."

Was he angry about it?

"No. I thought, 'This is what I signed up for’: I knew Nick and Richey and I know that what goes on in their heads I have no control over. But that's part of the excitement of being in the band, knowing that I could get behind 99.9 per cent of anything they could say or dream up and perhaps even make it come to life. But it scared the living shit out of me.

“At the same time, nothing could have made me try harder. That's probably why I kept going on Motorcycle, that's probably why I had such faith in Little Baby Nothing… That fear of failure was probably the biggest thing motivating me."

"If we had done the 16 million," says Sean, "I'm sure at the time we would have gone, 'That's it, fuck it.' Definitely. That was our whole purpose. We genuinely believed that was our whole mission statement. It would have been perfect."

So you were gutted when it didn't?

"Oh, absolutely. Devastated."

But the silver lining was that you still had a job and a band to go to...

"We wanted to be truthful to that purpose," he says firmly. "So if the second album had sold that many, then that would have been it. The trouble is, it's just kept going and kept going and kept going. We're still here."

Originally published in Classic Rock, February 2013.

Manic Street Preachers are touring this year. Visit their site for dates.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.