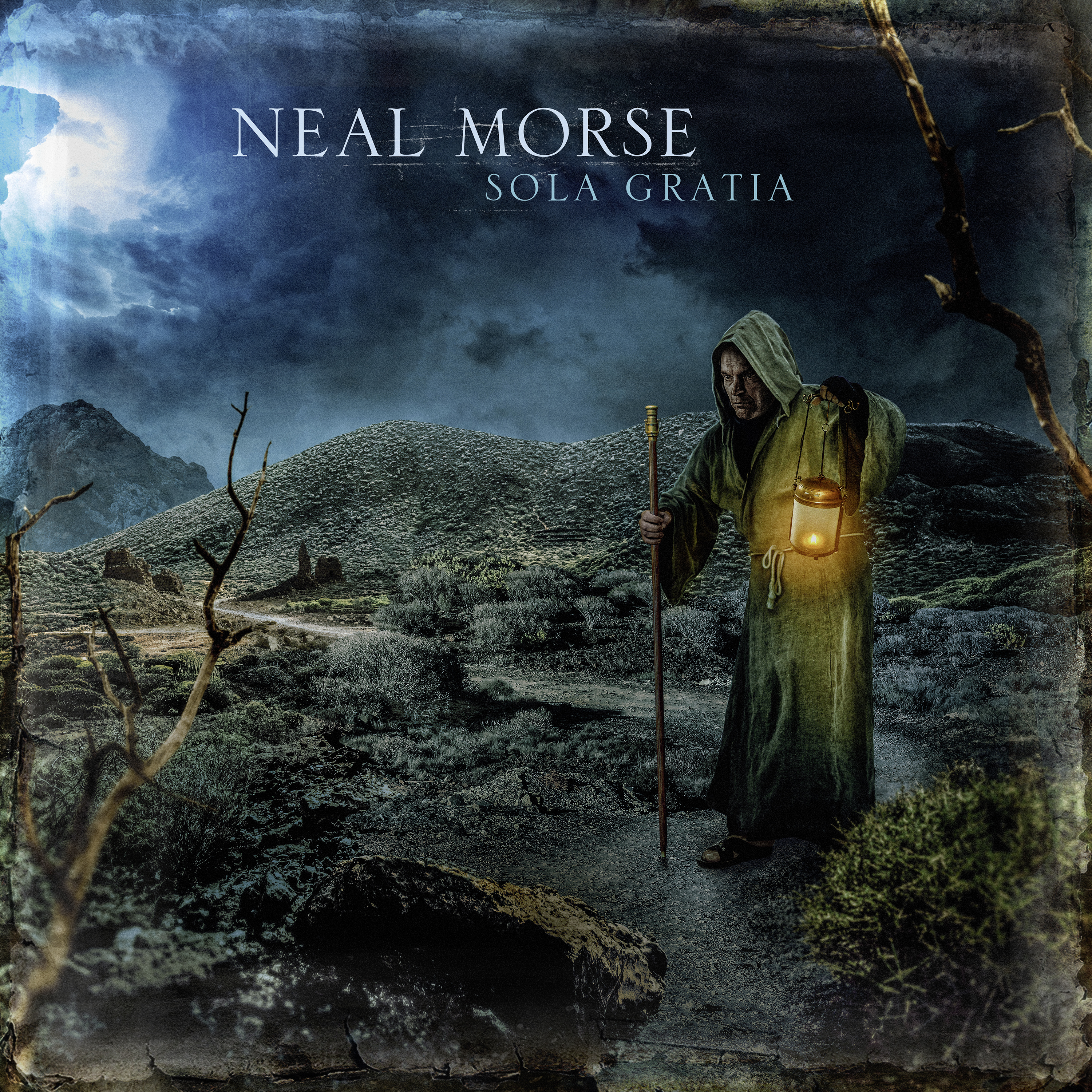

It’s tempting to look for parallels between the Biblical conversion of St Paul the Apostle on the road to Damascus and Neal Morse’s decision, two decades ago, to leave Spock’s Beard in the wake of his own spiritual awakening. Beginning with 2003’s Testimony, Morse has used his music as a vehicle to express his faith and with Sola Gratia he turns his attention to the story of Paul.

For anyone who’s a little rusty on their Bible scripture, Paul was a Pharisee who persecuted the early Christians until he experienced a vision, after which he devoted his life to spreading the new faith. He’s a key figure in the New Testament, in which 14 of the 27 books are attributed to Paul.

In keeping with Morse’s previous concept albums, such as Jesus Christ: The Exorcist and The Similitude Of A Dream, his message may be spiritual yet the delivery is unmistakeably prog. The kernel of the concept arrived while Morse was on vacation in February, before he came home to write and record the music while in lockdown through March and April.

“There was a whole month where my wife and I didn’t leave the house, ever,” he says. “It’s been weird, but I feel like the Lord has helped us to make some lemonade out of these lemons.”

Being in lockdown meant that Morse’s long-time collaborators – drummer Mike Portnoy and bassist Randy George – recorded their contributions remotely. “I wouldn’t say it was comfortable. I much prefer to be together in the room, no doubt about it,” says Morse, but he was determined to press on, particularly because he wanted the album finished in time to debut it live at MorseFest in September. “I’m used to bouncing things off those guys and I didn’t really have that,” says Morse. “Even on the earlier concept albums that I made with them, the One album for example, there was a restructuring that we did together that really helped it.”

Instead, he sent Portnoy and George a draft of the record, which had Morse playing all of the parts himself. “Even real drums!” he says. “That was funny in some of the fiddly bits. My feet are terrible; I can do okay stuff with my hands. I asked them, ‘Hey man, ideas? Arrangements? What are you thinking?’ And they said, ‘We love it, we’ll just play to it.’ So that’s what they did.”

That didn’t mean there was no room for the unexpected as Portnoy and George put their indelible stamps on the music. For Morse, that moment when the tracks come back from the other musicians and he listens to them for the first time is like opening presents on Christmas morning. “When I first put Mike’s drum solo in [second single] Seemingly Sincere into the session and listened to it, I was screaming in the studio all by myself. It’s wonderful,” he says. “Music always should be a surprise. We should be moved and thrilled as we’re working on it. Often it can become like a job; [if] we do it too often and too long we can lose the wonder, so I try to hold onto that.”

In the same vein, the writing process is rarely a straight road from conception to completion. Instead, the muse can lead Morse in directions unforeseen. The most famous moment in the story of St Paul the Apostle is his conversion, which seems like the obvious place to start. Instead, other ideas, including the martyrdom of St Stephen, began to assert themselves. “Originally when I first started writing, I thought I would get to the ‘road to Damascus’ experience early,” says Morse. “In the Book Of Acts, we meet Paul and then that happens; that’s really the beginning of his story, and that’s what I thought was going to happen, but as I began to write it, it seemed like there were more and more song ideas. One of the later things I wrote was Never Change and that was a longer piece, then Seemingly Sincere flowed out of that. Then I looked at the clock, I’m like 45 minutes in and he hasn’t even had his spiritual awakening. I wound up spending more time on the stoning of Stephen. I wasn’t planning on that, it just flowed that way.”

Morse compares the process of making a concept album to writing a novel. All the pieces must meld together to produce a cohesive whole. “It’s got to fit together lyrically, musically and it needs to have an arc: a story arc and a musical arc that works,” he says.

However, since this is a prog album, there are instrumental interludes, like Sola Intermezzo, when the players really get to cut loose and shred. “Oh yeah, that’s something we joke about in the Neal Morse Band,” says Morse. “It’s funny sometimes, you’re telling the story and saying all this poignant stuff and then well, we’re a prog band, so now we’re going to play really fast. Bear with us, we’ll get back to the story later. On this kind of an album you want to have space, you want to have some instrumental playing that’s interesting, you don’t want to have song, song, song. That doesn’t seem to be the right flow. There were quite a few more little proggy bits that I had improvised on the original draft that I cut out. That was the challenge of writing by myself, what to leave in, what to leave out, making those hard decisions completely on my own, completely isolated.”

Without any of the album’s contributors at hand, Morse had to rely on his own judgement as he wrote and assembled Sola Gratia. The goal was to make sure that every piece of music felt right and honestly expressed what Morse was feeling when he wrote it, but it’s not always easy to gauge when a piece is finished or when more tinkering is required. “There are several times when I’m going, ‘Should I stop now?’” he says. “It’s like you’re on the journey and you come up on a precipice, you’ve travelled through the song and now you’re up on this overlook. Should I listen back from the beginning and get perspective, or should I plough on with whatever I’m feeling? Being rather impulsive as I am, I generally just plough on. I don’t want to lose the momentum.”

He often finds it helpful to sleep on a work in progress and return to it in the morning with a fresh set of ears, but it’s all about trusting in how the music feels. “It’s very instinctive,” he says. “I’m half kidding when I say I pray a lot, but I do pray a lot because I’m not sufficient for these things. I feel like I need guidance and it’s hard to know what’s right, so I pray that I’m making the right decisions. The goal of the whole thing is to touch people’s hearts and thrill their minds and emotions. I don’t feel like I can really do all of that on my own, so I seek a lot of help.”

Despite his devoted fanbase, Morse occupies a strange, singular place in the musical landscape: Sola Gratia is far too progressive for the contemporary Christian music scene while the religious content can be alienating to secular prog fans. “Thank God the prog community stayed with me,” he says. “I’m a man without a country in a sense, musically. The Christian music business, they don’t know what to make of me. It’s not in their wheelhouse at all. Even some of the more normal worship albums that I’ve done have not been anything that has interested them. I’ve not many any inroads there at all. Then the Christian content of my albums is a challenge for the prog community, so I’m just thankful that enough people have stayed with me to make this all possible.”

Ultimately, Morse believes musicians must be true to themselves, ignoring pressures from labels or worries about fan expectations. “We need to disregard any ideas of commerce and just do whatever it is we feel to do on any given day. I remember thinking, ‘Man, I don’t know if anybody is going to accept this!’” he says about his leap of faith when he left Spock’s Beard to make the Testimony album. “Lo and behold, what a miracle it was, we had such a wonderful tour. I remember praying about it and feeling like I should ask Mike if he wanted to play on it and I had doubts if Mike was even going to want to be involved. It’s not everybody’s thing, I understand that. I put it out there to Mike, sent him the demos, and he was like, ‘Man, I’d love to, I love it.’ I was like, ‘Wow, hallelujah!’ I’ve been shocked all the way along, thanking God all the time for the music and the audiences and all of it.”

This article originally appeared in issue 113 of Prog Magazine.