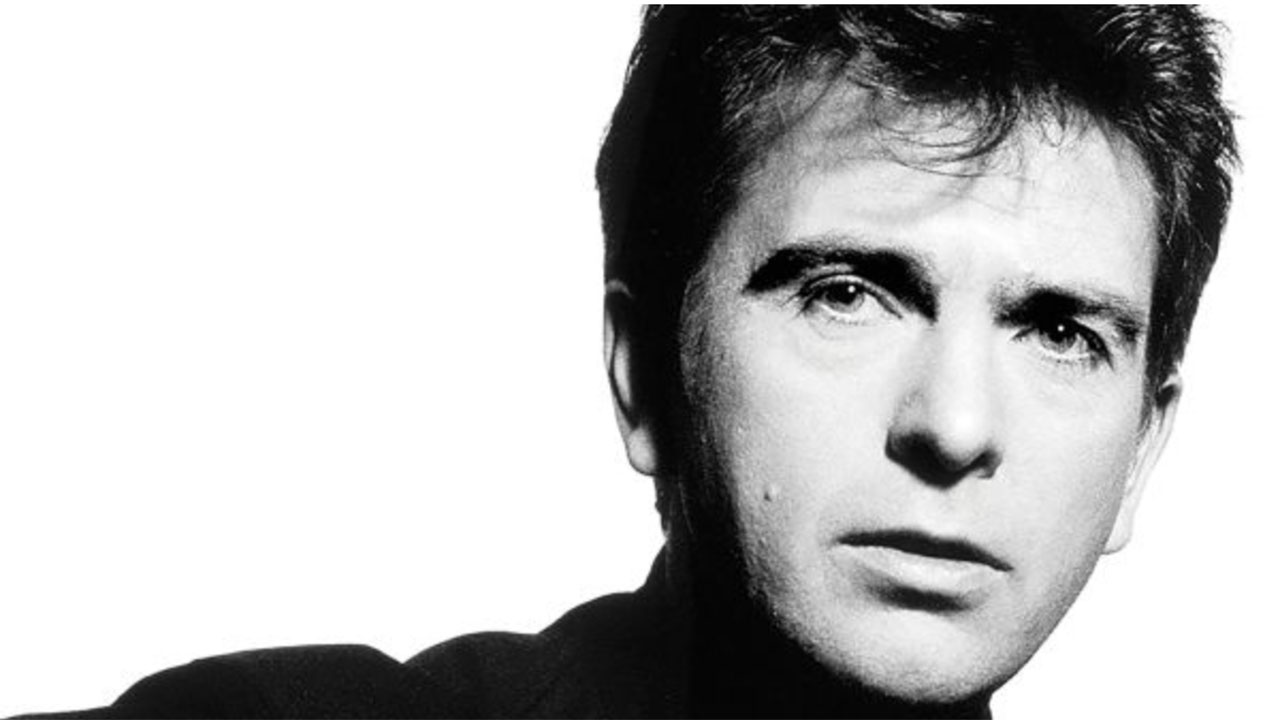

"There wasn't an option to go and hide in the shadows any more": How Peter Gabriel made So and became the world's biggest-selling cult artist

In 1986 Peter Gabriel released his fifth studio album So. It was a huge international hit. This is how it happened

In 1986, Peter Gabriel released his fifth studio album, So, a record of high commercial values that chimed perfectly with its era. It appeared he had junked all of his progressive past and wrapped everything in a commercial sheen. Although So came in a glossy, Peter Saville-designed sleeve featuring an unambiguous portrait of Gabriel, and the album tapped into the nascent worldwide CD phenomenon, on closer inspection, it’s still a progressive rock album at heart. With its references to literature, art, science, imaginary characters and, frequently present in Gabriel’s work, having a good old fumble, combined with virtuoso musicianship, So is very much business as usual.

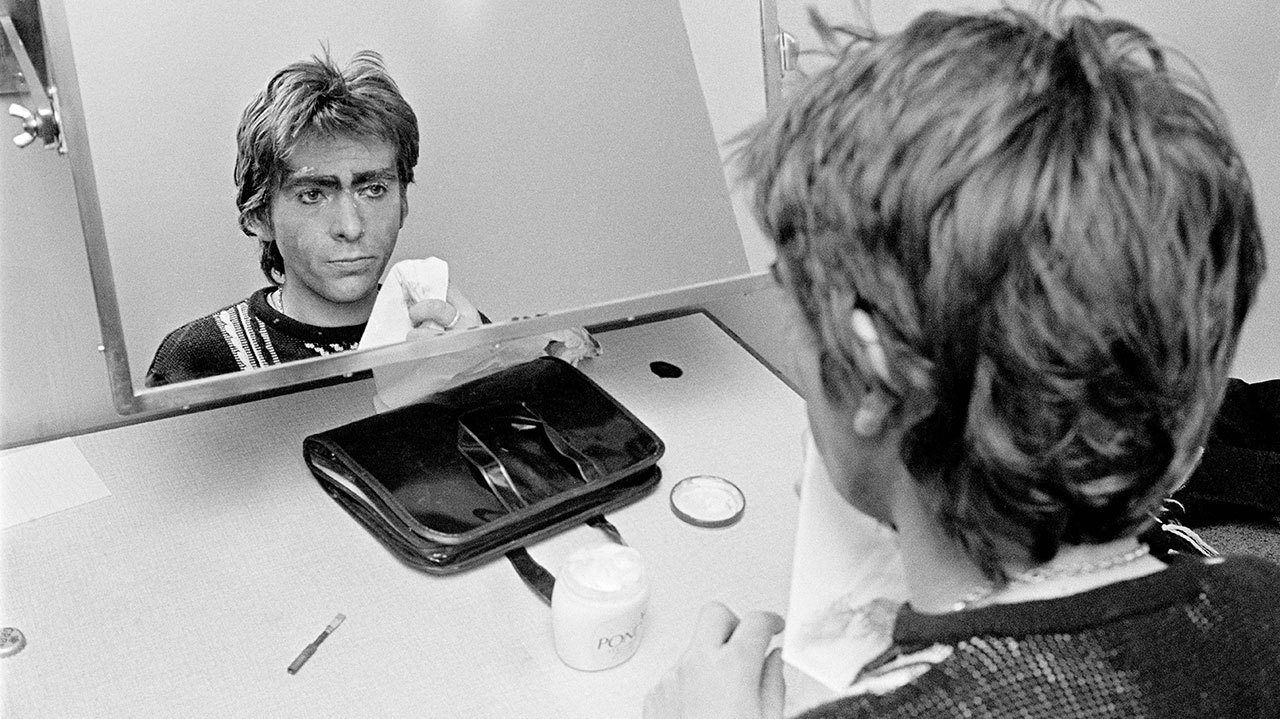

Sessions for the album began at Gabriel’s Ashcombe House studio in Bath (or ‘Shabby Road’, as it had been christened during his fourth album, also known as Security) in early 1985. Although Nile Rodgers and Bill Laswell had been considered to produce, Gabriel chose to record with Canadian Daniel Lanois, with whom he’d worked on the soundtrack to the film Birdy. Accompanied by guitarist David Rhodes, the three quickly dubbed themselves the Three Stooges and crafted the basic tracks for the album.

“By having just the three of us, we had this ‘turning up for work’ kind of humour: we’d wear these construction-worker hard hats,” Lanois said in his autobiography.

By not involving other musicians immediately, Gabriel, in theory, could head down fewer cul-de-sacs, as had become the norm on Security, which had taken 18 months to record. Lanois was aware of Gabriel’s love of a distraction and attempted to keep him on track. So, of course, went to the wire with Gabriel’s customary reticence in providing final lyrics, much to the frustration of Lanois. In order for Gabriel to finish the record, Lanois actually nailed him inside the barn at his house to complete the words.

Within a year, the album was ready, bristling with top-drawer musicianship (Stewart Copeland, Youssou N’Dour and Nile Rodgers all took part) and a surfeit of ideas. The opening Red Rain is dark and brooding, designed to ‘crash open at the front’. Its lyrical themes came from Gabriel’s on-off concept Mozo, about a wandering stranger. It’s based loosely on the medieval work Aurora Consurgens, full of alchemical, religious and apocalyptic imagery, attributed to St Thomas Aquinas. Gabriel was enthralled with the idea of Mozo, a Moses-like character, who had appeared in glimpses in his previous solo work. Red Rain came from a dream that Gabriel had of a big, red sea being divided, and glass bottles shaped like humans filling up with blood. Although it was new, full of shiny 80s modernism, it seemed as if Gabriel from 1974 was talking, rather than the new, lean, handsome heartthrob he’d become.

It was Sledgehammer, of course, that was to change the course of Gabriel’s career. It presented him as a child in a sweet shop, dabbling in all manner of sexual innuendo. Working with his first love, soul music (just listen to the early Genesis demos for glimpses of prog-soul), the song was a celebration of life that stunned the listener on first hearing.

For once, Gabriel had produced a straight-out-of-the-box, unbelievably catchy hit single. After its wonderful false beginning, where the E-mu Emulator II shakuhachi bamboo flute sound (that seemingly was then placed on virtually every record that followed it) drops away, it sets up the dirtiest, greasiest horn break. It confounded expectations. The song sounded like the future, a time capsule of the most up-to date production available in 1986.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Karl Bartos told me that when Kraftwerk were making Electric Café they went into the Power Station where Gabriel was doing overdubs on So and Sledgehammer was put on,” Kraftwerk biographer David Buckley said. “They were knocked back by how fantastic it sounded. They felt their record was puny sonically by comparison, even though it’s a completely different genre of music.”

An evocative ballad, Don’t Give Up was partially inspired by the startlingly evocative Dorothea Lange pictures of Americans during the Great Depression. Written as a duet, Gabriel initially envisioned Dolly Parton to sing with him. Instead he turned to his great friend, Kate Bush, who was then enjoying huge commercial success in the wake of Hounds Of Love, to add the impassioned female vocal part. Over the gentle swell of Richard Tee’s gospel-influenced piano part, the song was a masterpiece of understatement that was in step with the straightened times lurking beneath the shiny veneer of the era.

Don’t Give Up is arguably Gabriel’s most powerful statement. In 1981, Margaret Thatcher’s Employment Secretary Norman Tebbit infamously used an analogy about his father being out of work in the 30s, and instead of rioting, he got on his bike and looked for work. This became interpreted popularly as telling the unemployed to ‘get on their bike’ to find a job. Gabriel’s tale of a dispirited man at the end of his tether looking for work touched a raw nerve with millions of listeners in the UK and, latterly, the world. The song, with Gabriel’s despair in the verses and Bush’s words of hope in the chorus, has gone on to be arguably Gabriel’s most loved composition.

After such high drama, That Voice Again is a beautiful, Byrds-like pop song that often gets overlooked amid the album’s plentiful highlights. Originally entitled First Stone, it sounds almost as if Gabriel had taped one of the therapy sessions that he had been going through. Musically, it’s relatively simplistic, with Rhodes playing jangling Rickenbacker over the rhythm section of drummer Manu Katché and bassist Tony Levin.

Mercy Street was another standout. Gabriel had been reading the work of American poet Anne Sexton after having become interested in her work through the book To Bedlam And Part Way Back. Sexton had committed suicide at the age of 45 in 1974, leaving a slender yet highly confessional body of work, and the gentle, lilting rhythm of Gabriel’s song supports lyrics that allude to this. Percussion for the track was recorded by Gabriel in Rio de Janeiro by seasoned player Djalma Correa. With its deeply reflective tone and affecting vocal, Mercy Street became one of Gabriel’s most popular numbers and a staple of his live set.

Big Time was a sardonic reflection on the music business. It takes the opposite viewpoint of the Jacob character in I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe); it was time, after all, to try for that future in the fire-escape trade. Gabriel wrote the lyrics examining the dichotomy of his character, and perhaps realising it was fame he craved after all. The track was an obvious choice for a later single from the album in the UK, and the second single in the US, where it reached Number 8. Clean cut and funky, this was clearly how the States liked their Gabriel.

We Do What We’re Told (Milgram’s 37) had been around for a considerable period, originally recorded as far back as 1980’s Melt and seriously in the running for 1982’s Security. As it is, it sounds like the last link with that era. Strange, undercooked and difficult, it was about Professor Stanley Milgram’s social psychology experiment from 1961: volunteers assessing how far they would be prepared to follow an authority figure, even if it was in complete opposition to their conscience or their views. Gabriel explored how people are conditioned to believe in dictators and support war. With its patter of Jerry Marotta’s processed drums and L Shankar’s squalls of violin, and two overdubbed guitar tracks by Rhodes, it’s a disquieting interlude, proving to Gabriel’s new-found audience that it was still within his power to unsettle.

This Is The Picture (Excellent Birds) was adapted from the track Gabriel had written with Laurie Anderson for her Mister Heartbreak album. On it, he worked again with Nile Rodgers.

“I recorded my part in New York,” Rodgers recalled. “In those days I was gigging, and that was the height of my life. Sometimes it’s hard for me to remember what studio, what work, where I was. I loved that sound that Daniel got.”

What Gabriel wanted Rodgers to do was to add his remarkable, rhythmical guitar playing to another skeletal idea, and one that had been inspired by the Korean video artist Nam June Paik, who used to make TV shows. He had asked Laurie Anderson and Peter Gabriel if they would like to collaborate, and they worked quickly to produce this groove.

The album closed with another of Gabriel’s most loved songs, In Your Eyes, originally titled Sagrada Familia, inspired by the cathedral in Barcelona. Alluding to Antoni Gaudí and rifle heiress Sarah Winchester, the song was multi-layered and deeply affecting. The power of the track was made real by the stunning guest vocal performance from Youssou N’Dour, who sings in his native language, Ouoloff. In Your Eyes was featured dramatically in the Cameron Crowe film Say Anything in a sequence when protagonist Lloyd Dobler (John Cusack) plays it loudly from a ghetto blaster.

So was released on May 19, 1986. Sledgehammer was issued shortly before it and put Gabriel squarely into the charts and hearts of millions. With its Brothers Quay/Aardman Animation video, Gabriel showed that, after all, he was a song and dance man. Here was the flower-headed pipecleaner of Willow Farm, vamping it up for the MTV generation.

The video was a viral sensation long before such things existed. The single reached the top spot in the US. Gabriel was delighted. The most affectionate homage to the music that originated from deep within America, here was almost the ultimate tribute. An introverted white boy from a privileged British background convincingly interpreting the music of the impoverished, segregated south of America. And somehow, it not only worked, but absolutely nailed it.

So, just funky enough, just obscure enough, just nostalgic enough, fitted perfectly with the CD generation. Gabriel began to attract a breed of listener that welcomed him as a ‘new artist’. This was liberating but would ultimately prove constraining. Although a super-slick short single had always been part of Gabriel’s oeuvre, how willing would this new audience be when he was experimenting?

Writing in 2012, Gabriel said: “When I first heard So, I was really pleased. It wasn’t as rich with texture and sonic experiment as my earlier albums, but it had a very strong spirit. It wasn’t like I was an obscure artist. I’d had hits with Shock The Monkey, Games Without Frontiers and Solsbury Hill, but after each of them I’d purposefully retreated partially back into the shadows.

“With So this was the end of the idea of me being a sort of cult artist at the fringes of the mainstream, especially in America. There wasn’t an option to go and hide in the shadows any more.”

There were no shadows left to hide in. Gabriel was in the full glare of the spotlight, and for the first time in his life, it shone really very brightly indeed. And he did it with So, largely a progressive rock album.

Daryl Easlea has contributed to Prog since its first edition, and has written cover features on Pink Floyd, Genesis, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel and Gentle Giant. After 20 years in music retail, when Daryl worked full-time at Record Collector, his broad tastes and knowledge led to him being deemed a ‘generalist.’ DJ, compere, and consultant to record companies, his books explore prog, populist African-American music and pop eccentrics. Currently writing Whatever Happened To Slade?, Daryl broadcasts Easlea Like A Sunday Morning on Ship Full Of Bombs, can be seen on Channel 5 talking about pop and hosts the M Means Music podcast.