“To be honest, I should never have made The Wall.”

So said director Alan Parker in the press notes accompanying the release of the 1982 film – not exactly the stock upbeat response you get from a filmmaker promoting his latest work.

Although he admitted to being “very proud of it”, Parker added that “the making of the film was too miserable an exercise for me to gain any pleasure looking back at the process.” The intervening years may have eased the pain somewhat, but they hardly gave a rose-tinted hue to Parker’s memories of the experience.

“When I go to film festivals and they show my films, they always include The Wall and it’s always packed out. So it always appears wimpy to say I hated making it. I have mellowed a bit, and say it was a ‘tortured but highly creative time’. Not to be repeated.”

The primary cause of Parker’s unhappiness was dealing with two artists who were both equally strong-willed and reluctant to compromise. Roger Waters and satirical cartoonist Gerald Scarfe had created the extravagant stage show of The Wall and had been working together in formulating ideas for the film before Parker was hired as director.

The collaborative process proved to be equally stressful for Waters, who declared in the 1999 documentary included on the DVD of Pink Floyd The Wall: “Making the film eventually became an unnerving and unpleasant experience because we all fell out in a big way.”

Waters pointed to the fact that “there were serious clashes in terms of styles and philosophy”, and that he, Scarfe and Parker were all used to getting their own way and found compromising difficult. It’s an assessment shared, and expressed in rather blunter terms, by Parker: “Yes, I think that’s true. Three megalomaniacs in a room, it’s amazing we achieved anything.”

When Parker was asked in a 2003 interview by Michael Parkinson about his contentious relationship with Roger Waters, he said: “Actually, anybody who knows Roger; you can’t say hello to him without being contentious.”

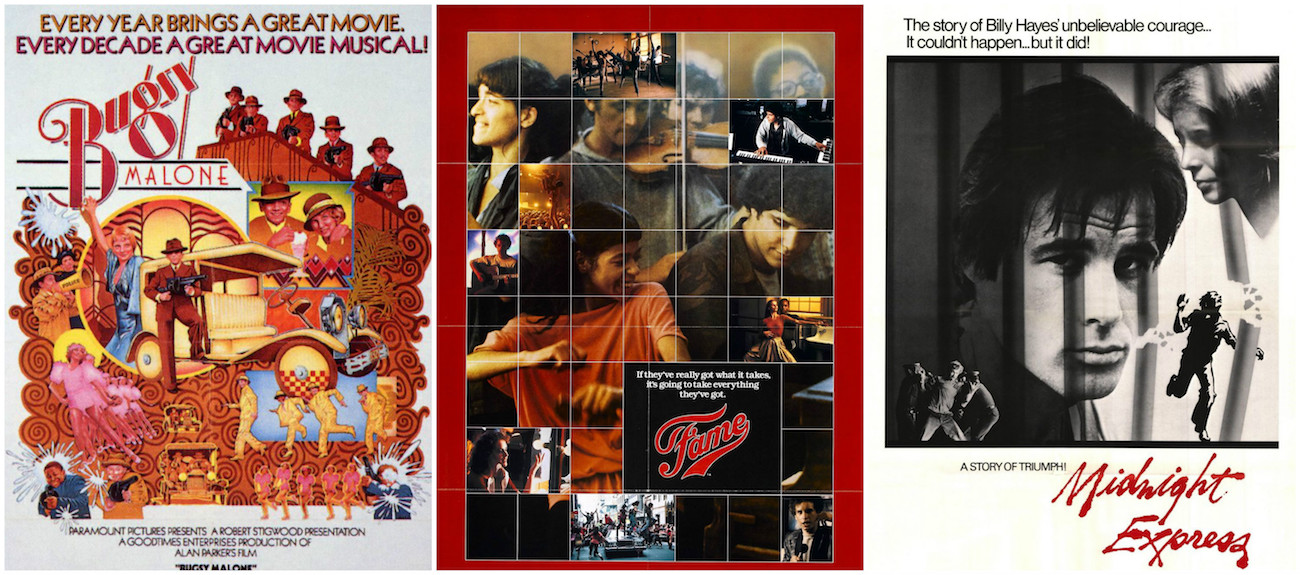

For Parker, a self-professed “Floyd devotee since A Saucerful Of Secrets”, the opportunity to work with the group was an appealing one. The 37-year-old English director was by then a hot Hollywood property thanks to an already impressive list of credits that included Bugsy Malone, Midnight Express and Fame. He was about to start filming Shoot The Moon in San Francisco with Diane Keaton and Albert Finney when a casual conversation with EMI executive Bob Mercer led to a meeting with Waters.

Parker: “On first meeting it was obvious that Roger wasn’t the typical zonked-out rock star, as we sat in his kitchen talking over the history of the piece and he demonstrated the evolution of the work with snippets of original demo tapes he’d made alone locked behind the wall of his previous house in the country. These were raw and angry – Roger’s primal scream, which to this day remains at the heart of the piece.”

At this stage, with his thoughts focused on his next project, Parker had no intention of directing the film even though “Roger was very persuasive”. When asked why he thought Waters wanted him to direct, Parker is uncertain: “No idea. Maybe he liked Midnight Express. Dave Gilmour once referred to Midnight Express as my Dark Side Of The Moon, which was very flattering.”

It was while in San Francisco that Parker got a call from Waters proposing the two of them produce the movie, and have Michael Seresin (Parker’s long-time cameraman) and Gerald Scarfe team up as directors. “The idea appealed to me because it meant that I could be vicariously involved with a project I had great hopes for, without having to sweat the blood that directing requires.”

To get an idea of the task ahead, Seresin and Parker flew to Germany to see Pink Floyd performing The Wall live. As Parker recalled: “It was impossible not to be impressed by the immensity of the proceedings. The concert was rock theatre on a mammoth scale, probably more grandiose and ambitious than that genre had ever achieved before; a giant, raging Punch And Judy show.”

Likening it to a colossal puppet show maybe not quite how Roger Waters saw his tortured semi-autobiographical story of alienation, but Parker was clearly wowed. In particular he was struck by Scarfe’s disquieting animation and the impact the memorable sequence involving the copulating flowers had on the audience. Parker recognised that the powerful combination of the live music, the animation projected on the large triptych screens and the construction of the vast wall across the stage “created a theatrical sensation that would be hard to improve on in the confines of a regular movie theatre screen”.

Backstage after the show, another thing that struck Parker was how “everything was dominated by Roger’s autocratic, almost demonic control over the entire proceedings”. When he is asked for an example of Waters’s controlling influence, Parker recounts one telling observation: “Backstage during the concerts they had four caravans in a square, one for each of the Floyd. Three faced inwards to a communal chatting, drinking area; Roger’s caravan faced outwards with his entrance away from everybody else.”

After filming Shoot The Moon, Parker returned to London and began working with Waters and Scarfe at Scarfe’s home in Cheyne Walk on the Thames, developing the scant screenplay Waters had written. “For Roger it was never a case of writing a script,” said Parker, “it was about delving into his psyche to find personal truths; I was more interested in the cinematic fiction.”

The original intention had been to include The Wall concert footage, but the attempts to shoot five concerts at Earl’s Court all proved disastrous. “Michael and Gerry didn’t gel as directors, or even realise what exactly they should be doing,” Parker observed. “As for myself, I was quite useless as an impotent director and even less useful as an impostor producer, and began chain-smoking for the first time in my life.”

As a result, Parker agreed to assume the director’s role and, with his appointment, the whole concept changed. The idea to include concert footage was abandoned, so without the appearance of the other three members of Pink Floyd – David Gilmour, Richard Wright and Nick Mason – it was determined that Waters should no longer play the film’s central character of Pink.

Given that it was Waters’ story, and knowing his obsessive, controlling nature, had it been difficult for Parker to persuade him to relinquish the role? “Curiously it wasn’t difficult,” said Parker. “He was quite cool about it. And he’s not daft. He wasn’t, after all, the lead singer of the band, and so had no aspirations to be Laurence Olivier.”

Based on his 1980 live review of The Wall for the NME, celebrated music journalist Nick Kent would no doubt have endorsed this decision: “Playing the principal character is possibly courageous in terms of trying something different and more taxing, but it’s also a grave error: Waters has no stage presence, and he is incapable of projecting anything beyond the most banal breast-beating most commonly associated with youth-club amateur dramatics.” Parker was equally unimpressed with Waters’s acting, saying Waters was “closer to Albert Speer than to Albert Finney”.

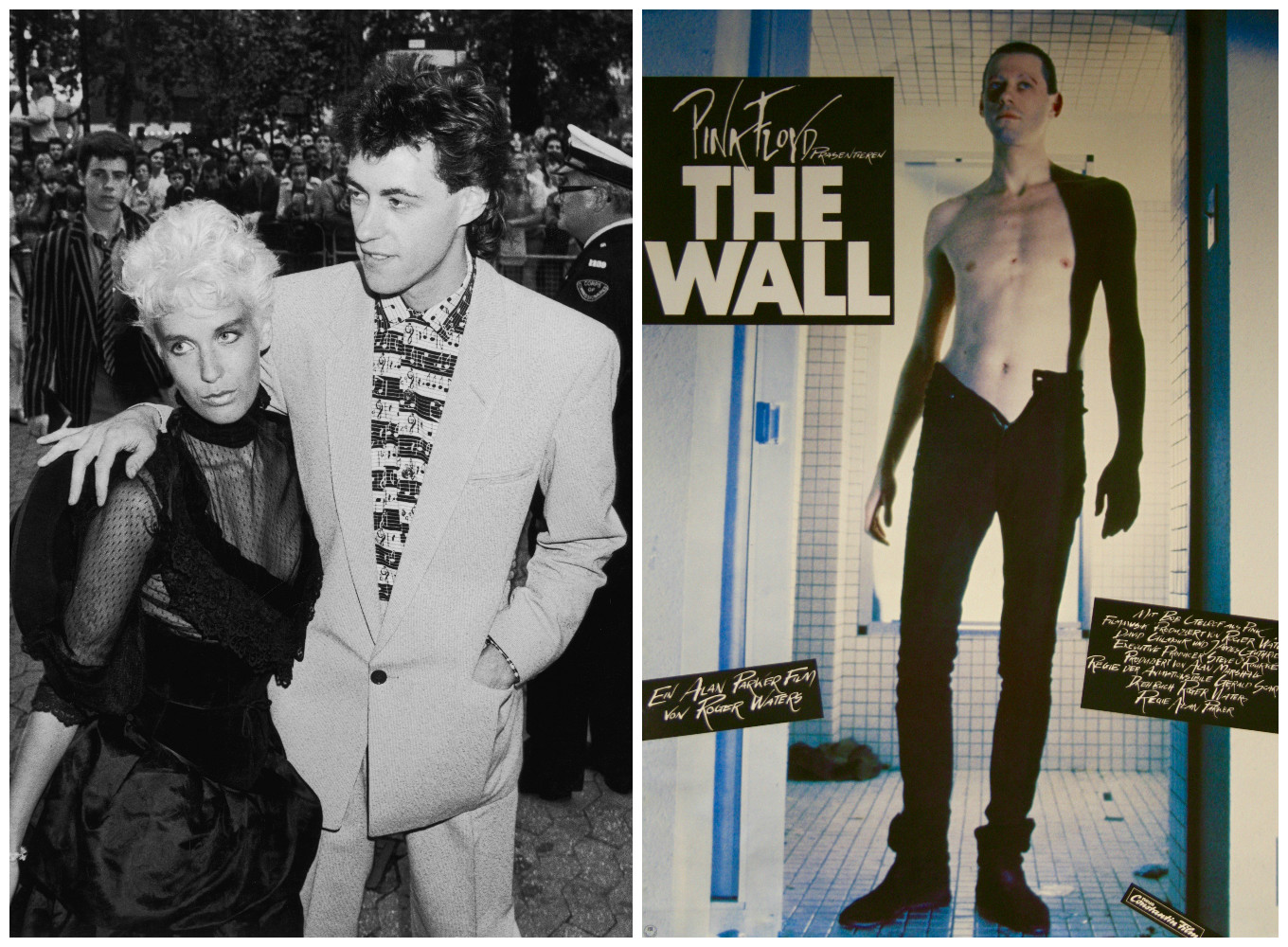

So the search for a suitable replacement for the role of Pink began. Impressed with Bob Geldof’s performance in The Boomtown Rats’ video for I Don’t Like Mondays, he approached the singer, who confessed to not being a big fan of Pink Floyd. When asked by Parker if he’d seen The Wall, Geldof quipped: “Yes, I’ve got one at the bottom of my garden.”

Parker, unsure if Geldof had the acting chops to portray Pink’s emotionally vulnerable descent from rock icon into catatonic alienation and emergence as a megalomaniacal dictator, invited him to do a screen test. Parker was more than impressed with Geldof’s delivery of Brad Davis’s charged, courtroom speech from Midnight Express. “He did it wonderfully, surprising us all with his control,” he said.

With Parker won over, it was then just a question of getting Waters to agree. Fearful that Geldof wouldn’t be able to sing the songs, there was speculation he might just mouth to Waters’s voice.

“Alan convinced Roger that Bob was the right man for Pink and also that Bob should re-record the songs,” explained the film’s producer, Alan Marshall, on the documentary DVD. The choice of Geldof gave the project new impetus, Parker felt: “By choosing Bob we did give it a fresh lease and a new life which I think is very important to the piece.”

Filming began on September 7, 1981 with Parker working from the skeletal script. “It wasn’t a conventional screenplay… Sometimes we had five lines of description in the ‘script’ to go on and some days we had a great coloured painting by Gerry to set us off on the chaotic, anarchic journey in search of a film.”

It was an unfamiliar task for Parker, who struggled to make sense of the story he was telling while also clashing with its originator. At one point, as Gilmour told Classic Rock: “We had to persuade Parker to come back. There was big money invested. And as the entire film company worked at Pinewood they were going to be loyal to Parker, because he’s a film maker, not to Roger. In my view it wasn’t workable. We had to go through this whole power thing. Which I suspect Roger has never forgiven me for.”

Battling with Waters wasn’t Parker’s only concern. “The skinheads were our biggest problem,” he wrote at the time. In the film’s climactic scene featuring Pink addressing a violent fascist rally, 380 real skinheads were hired. “How could we make them behave in a civilised and safe manner? Stop them from being bored; stop them from kicking everybody’s head in. It wasn’t easy teaching them to understand the difference between reality and the filmed illusion.

“They started to think it was real, so it was kind of difficult to control them in some of the more excessive, uglier scenes that I filmed. You always wonder as a film director if you might be crossing a line when you actually get people to do things that are not very pleasant.” He remembered one troubling moment when a group of the “Tilbury Skins” adorned in the jackbooted, Nazi-style uniforms of Pink’s ‘hammer guard’, went into a pub, terrifying the locals.

- The story behind Pink Floyd’s The Wall album cover

- The Top 10 Best Pink Floyd Roger Waters Songs

- Fly On The Wall: Pink Floyd Sink Venice

After 61 long, arduous days, 977 shots, 4,885 takes and 350,000 feet of film, shooting finished. In addition to the live footage there was more than 15 minutes of Scarfe’s animation comprised of more than 10,000 drawings. It took eight months to complete the mammoth task of editing everything into a cohesive 99 minutes before Pink Floyd The Wall made its debut at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival. Two truckloads of the group’s concert PA system were taken over from England to boost the Palais’ sound system.

Parker remembers the Cannes screening as “a magnificent experience”. The combination of deafening sound and the film’s powerful imagery had quite an impact on the festival audience, which included some notable celebrities. “Stephen Spielberg stood up at the end and politely bowed towards me. He then shrugged to his neighbour, Warner Brothers studio head Terry Semel, clearly saying: ‘What the fuck was that?’”

It’s a question asked by many over the years. “It’s a mish-mash, an amalgam of lunatic ideas which are all Roger Waters’s really,” Parker said in a 2003 interview. “I think he’s the only person in the whole world who actually knows what it’s all about. I’m sure most of us didn’t. We all thought it was a load of old tosh, actually.

"I think it’s an interesting film, but I think it’s pretentious to kid you that anybody intellectually knew what we were doing. But maybe Roger did. The rest of us just made it up as we went along.” It turns out that even the man whose original idea lay behind it all remained uncertain about what it all meant.

“I’m confused,” Waters admitted in the documentary. One thing Waters is certain of is that, from his perspective, the finished film is “deeply flawed because it doesn’t have any laughs. It’s a pretty dour two hours.”

When Classic Rock directed that opinion of Waters’ to Parker, his reaction was one of surprise: “Good one, Roger! Well, let’s face it, the album and stage show aren’t exactly a hoot either. Are they flawed too for the same reason? Primal screams don’t have a lot of laughs. Carry On Up The Wall wasn’t exactly the brief! I snuck in a few smiles, but you can never escape Roger’s demonic black heart at the centre of the original work. If you want laughs, then watch The Commitments.”

For all the bewilderment and unhappiness associated with the film, Parker believes its pioneering aspects have endured rather well. “The special effects and animation techniques would probably be more sophisticated these days, but overall it still stands the test of time.”