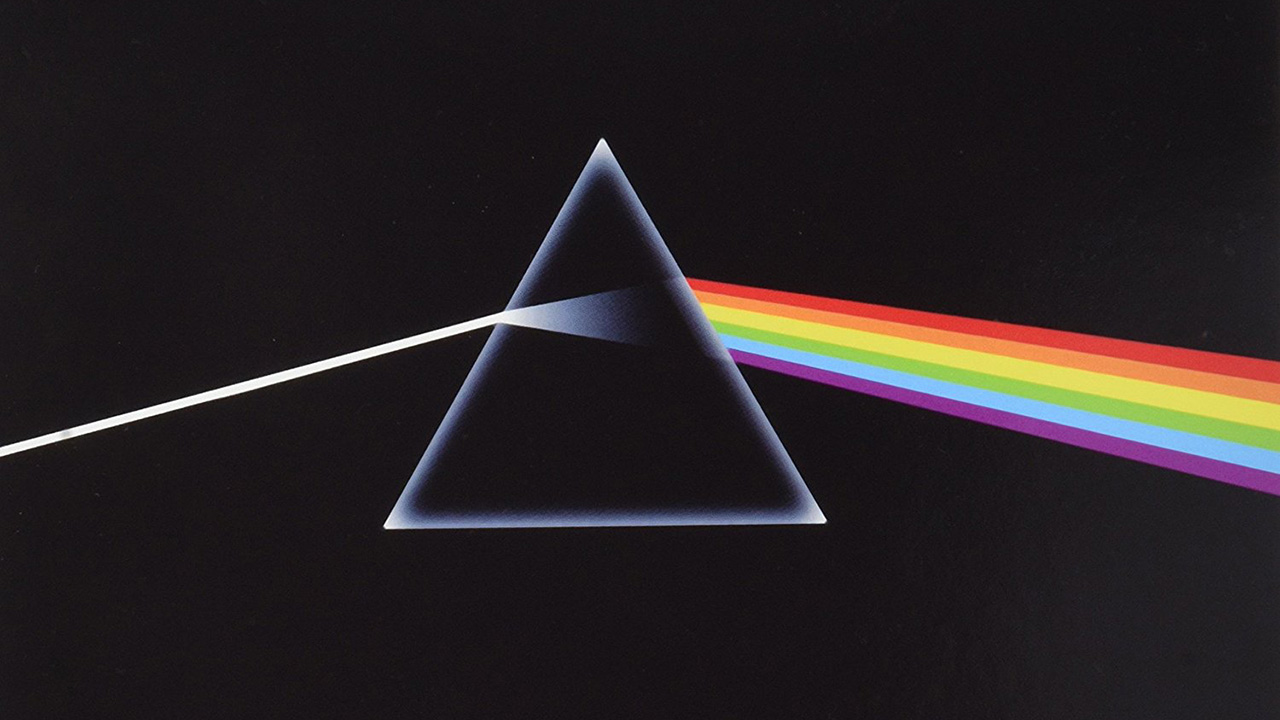

Almost 50 years since its release, Pink Floyd's groundbreaking eighth album, Dark Side Of The Moon, remains a monumental achievement in the history of rock music. Despite never reaching number one in the UK, and spending just one week at the summit in the US, it has since notched up 937 weeks (that’s 18 years) in the Billboard 200 Albums chart, and sold more than 45m copies worldwide. It was also recently voted the best rock album of all time by Classic Rock readers, and it's fair to say those guys know their shakes when it comes to quality music.

The album's story starts in a poky studio in west London in 1971, when the band embarked upon 12 days in a rehearsal room at Decca Studios in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead, London. They were working on a suite of music under the title Eclipse – which would, in due course, evolve into Dark Side Of The Moon.

"It began in a little rehearsal room in London," said David Gilmour of the album's early days. "We had quite a few pieces of music, some of which were left over from previous things."

"I think we had already started improvising around some pieces at Broadhurst Gardens," confirms Roger Waters. "After I had written a couple of the lyrics for the songs, I suddenly thought, I know what would be good: to make a whole record about the different pressures that apply in modern life."

The album slowly began to take shape. By the time 1972 rolled around, rehearsals had moved to the Rolling Stones’ rehearsal facility; a disused Victorian warehouse at 47 Bermondsey Street, South London. A grand enough setting for a creative project which would eventually come to eclipse Floyd's previous output in terms of both its scale and ambition. "We started with the idea of what the album was going to be about: the stresses and strains on our lives," says Nick Mason.

"We were there for a little while, writing pieces of music and jamming," adds Gilmour. "It was a very dark room."

Two weeks later, Pink Floyd began a 16-date UK tour at The Dome, Brighton, which included the first live performance of Eclipse, now renamed Dark Side Of The Moon – A Piece For Assorted Lunatics. Naturally, the band decided their new material required an ambitious, demanding new stage set up to match. However, it was a move their technical teams weren't quite ready for yet. The performance was cut short midway through Money due to tech problems.

"In those days we didn’t understand how to separate power sufficiently between sound and lights," explains former Floyd roadie Mick Kluczynski. "It was the very first show any band had done with a lighting rig that was powerful enough to make a difference. So we had this wonderful situation where the fans were actually inside the auditorium, and we had [sound engineers] Bill Kelsey and Dave Martin at either side of the stage screaming at each other in front of the crowd, having an argument."

"A pulsating bass beat, pre-recorded, pounded around the hall’s speaker system. A voice declared Chapter five, verses 15 to 17 from the Book Of Athenians," wrote former NME journalist Tony Stewart at the time. "The organ built up; suddenly it soared, like a jumbo jet leaving Heathrow; the lights, just behind the equipment, rose like an elevator. Floyd were on stage playing a medium-paced piece… The Floyd inventiveness had returned, and it astounded the capacity house… The number broke down thirty minutes through."

Not to be deterred, Floyd continued on their tour well into February, playing Dark Side Of The Moon in a nascent stage of completion by this point. "The actual song, Eclipse, wasn’t performed live until Bristol Colston Hall, on February 5," says Waters. "I can remember one afternoon rolling up and saying: “I’ve written an ending.” Which was what’s now called Eclipse, or Dark Side. So that's when we started performing the piece called Eclipse. It probably did have Brain Damage, but it didn’t have ‘All that you touch, all that you see, all that you taste.’

"It was a hell of a good way to develop a record," says Mason. "You really get familiar with it; you learn the pieces you like and what you don’t like. And it’s quite interesting for the audience to hear a piece developed. If people saw it four times it would have been very different each time."

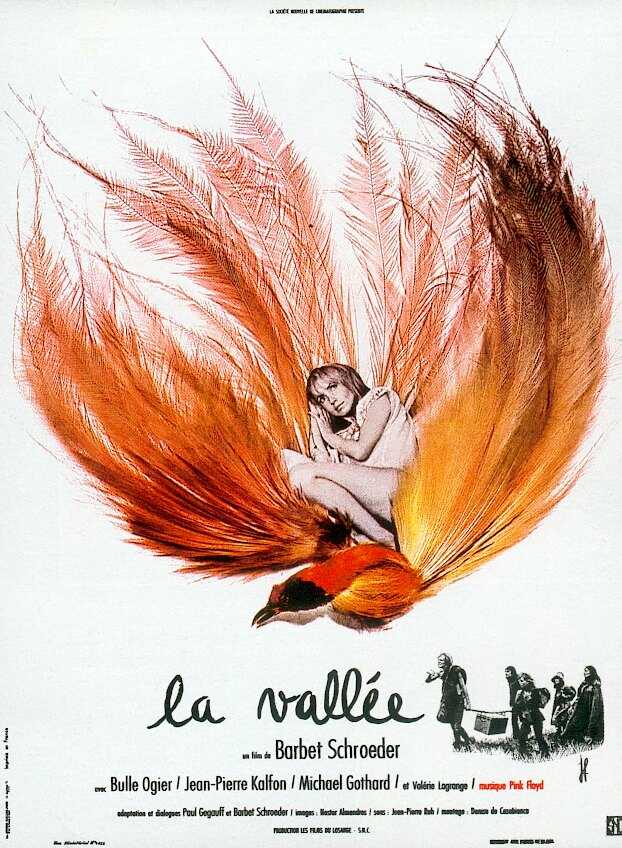

However, as February drew to a close, work on the recording of DSOTM was derailed by the obligation to record Obscured By Clouds, the soundtrack to the film La Vallée, followed by sporadic touring. The sessions eventually resumed at Abbey Road studios in May. Working titles for existing songs included Travel (eventually Breathe), Religion (The Great Gig In The Sky) and Lunatic (Brain Damage).

"Recording was lengthy but not fraught, not agonised over at all," says Mason of the sessions. "We were working really well as a band."

"I was definitely less dominant than I later became," agrees Waters. "We were pulling together pretty cohesively. Dave sang Breathe much better than I could have. His voice suited the song. I don’t remember any ego problems about who sang what at that point. There was a balance."

This balance, and the ease the band felt with one another, was reflected in the finished product. A harmonious record which flowed from beginning to end, it captured a rare snapshot of a band working at the peak of their creativity. Though it was a complex body of work, much of its success came from its deceptive lyrical simplicity. "Roger tried, definitely, in his lyrics, to make them very simple, straightforward, and easy to understand," says Gilmour. "Partly because people read things into other lyrics that weren’t there."

From this basis, the songs started to take shape. First up was Us And Them. "Rick [Wright] wrote the chord sequence for Us And Them and I used it as a vehicle," says Waters. "The first verse is about going to war, how on the front line we don’t get much chance to communicate with one another, because someone else has decided that we shouldn’t. The second verse is about civil liberties, racism and colour prejudice. The last verse is about passing a tramp in the street and not helping."

Next up was Money. "I knew there had to be a song about money in the piece, and I thought the tune could be about money," says Waters. "Having decided that, it was extremely easy to make up a seven-beat intro that went well with it."

"Roger and I constructed the tape loop for Money in our home studios and then took it to Abbey Road," remembers Mason. "I had drilled holes in old pennies and then threaded them onto strings; they gave one sound on the loop of seven. Roger had recorded coins swirling around in the mixing bowl Judy [his first wife] used for her pottery. The tearing paper effect was created very simply in front of a microphone, and the faithful sound library supplied the cash registers."

"Mason was always the guiding light in matters to do with the overall atmosphere," remembers DSOTM engineer Alan Parsons. "He was very good on sound effects and psychedelia and mind-expanding experiences."

Next, the band turned their attention to Time. The music was credited to the whole band but with lyrics by Waters. "Alan Parsons was a very good engineer," remembers Gilmour. "He had one or two production ideas that were very good. In a clock shop in Hampstead he had recorded the ticking clocks and made these tapes up to offer us an idea, which was great."

"Those big, grand keyboard chords are mine," said Rick Wright at the time. "Dave used to complain I’d write in these hard keys and weird major and minor sevenths, which is difficult to play on a guitar."

The band had just began work on The Great Gig In The Sky as the middle of the year loomed into view, and recording was again soon derailed because of touring, holidays and other commitments which kept the band occupied for much of the year.

Sporadic sessions were held in Abbey Road during October, during the first of which Dick Parry, an old friend of the band’s from Cambridge, overdubbed sax solos to Money and Us And Them. Later in the month a quartet of female session vocalists – Doris Troy, Lesley Duncan, Liza Strike and Barry St John – were brought in to embellish Us And Them, Brain Damage and Eclipse.

"They weren’t very friendly," said Duncan looking back. "They were cold, rather clinical. They didn’t emanate any kind of warmth… They just said what they wanted and we did it… There were no smiles. We were all quite relieved to get out."

Still, with their help, the finished album was starting to take shape. Waters completed work on The Great Gig In The Sky – a sensitive contemplation of death that ends up in a place you’d never expect given the pretty keyboards that Richard Wright brings to the tune’s first minute. "Are you afraid of dying?" Waters asked. "The fear of death is a major part of many lives, and as the record was at least partially about that. That question was asked, but not specifically to fit into this song."

Of course, one of TGGITS' most memorable moments was provided by a third party. "When I arrived they explained the concept of the album to me and played me Rick Wright’s chord sequence," says vocalist Clare Torry. "They said: 'We want some singing on it,' but didn’t know what they wanted. So I suggested going out into the studio and trying a few things. I started off using words, but they said: 'Oh no, we don’t want any words.' So the only thing I could think of was to make myself sound like an instrument, a guitar or whatever, and not to think like a vocalist. I did that and they loved it.

"I did three or four takes very quickly, it was left totally up to me, and they said: 'Thank you very much.' In fact, other than Dave Gilmour, I had the impression that they were infinitely bored with the whole thing, and when I left I remember thinking to myself: 'That will never see the light of day.' If I’d known then what I know now I would have done something about organising copyright or publishing; I would be a wealthy woman now. The session fee in 1973 was fifteen pounds, but as it was Sunday I charged a double fee of thirty pounds. Which I invested wisely, of course."

(In 2004, Torry sued Pink Floyd, arguing that her contribution to The Great Gig in the Sky constituted co-authorship. The band and record company EMI settled out of court, and the song is now credited to both Wright and Torry.)

It was 1973 by the time the final round of recording sessions began in Abbey Road Studio 2 in late January, focusing on Brain Damage, Eclipse and the instrumental Any Colour You Like. “It was – 'We’ve got nothing in this space… What can we do? We’ll have a jam.'” Remembers Mason. "And that’s what Any Colour You Like was – it’s just two chords. It starts off with the synth, which sets the mood. And you have this extraordinary guitar solo from Dave."

"I wrote Brain Damage at home," says Waters. "The grass [mentioned in the lyric] was the square in between the River Cam and King’s College chapel [in Cambridge]. The lunatic was Syd [Barrett], really. He was obviously in my mind."

The most innovative addition to DSOTM came as the sessions were ending, when Roger Waters hit on the idea of posing questions to Abbey Road staffers, Floyd crew members and other studio visitors. Their answers were recorded, and then edited and woven into the tracks at various points throughout the album. "We did about twenty people," says Waters. "The interviewees all had cards with questions printed on them like: ‘Have you ever been violent?’, ‘When was the last time you thumped someone?’ and ‘Were you in the right?’ and so on."

"Roger wanted to use things in the songs to get responses from people," says Gilmour. "We interviewed quite a few people that way, mostly roadies and roadies’ girlfriends, and Gerry [O’Driscoll], the Irish doorman. We also had Paul and Linda McCartney interviewed, but they’re much too good at being evasive for their answers to be usable.

"Gerry the doorman said: 'There is no da’k side o’ de moon, really, it’s all da’k.' And stuff like that, when you put it into a context on the record, suddenly developed its own much more powerful meaning."

The final Abbey Road session was held in Studio 2 on February 1st, 1973. "We’d finished mixing all the tracks, but until the very last day we’d never heard them as the continuous piece we’d been imagining for more than a year," says Gilmour. "We had to literally snip bits of tape, cut in the linking passages and stick the ends back together. Finally, you sit back and listen all the way through at enormous volume. I can remember it. It was really exciting."

The Dark Side Of The Moon was released in the US on March 17 and in the UK on the 24th. Four days later it hit No.1 in the US Billboard chart. In the UK it peaked at No.2. "We’d cracked it," says Waters. "We’d won the pools. What are you supposed to do after that?"

Sadly, the album marked the start of a creative struggle within the band which would come to plague their work and eventually end in their acrimonious demise.

"Dark Side Of The Moon was the last willing collaboration," says Waters. "After that, everything with the band was like drawing teeth; ten years of hanging on to the married name and not having the courage to get divorced, to let go. Ten years of bloody hell. It was all just terrible. Awful. Terrible."