"Why is that bloke singing like Syd?” asked Rick Wright. It was May 1994, and Pink Floyd’s keyboard player had just heard Blur’s new album Parklife. Pink Floyd were on tour in America and had gathered in guitarist David Gilmour’s hotel suite to listen to the album that had just supplanted their latest, The Division Bell, from the No.1 spot.

Wright might have been concerned that Damon Albarn sounded like his ex-bandmate Syd Barrett, but his was the only dissenting voice. “We wanted to hear what all the fuss was about,” bassist Guy Pratt told the author. “Most of us thought Parklife was very good.”

Pink Floyd could afford to be gracious in defeat. The Division Bell, released in March 1994, became the band’s first album since 1975’s Wish You Were Here to reach No.1 in both the UK and US. Their 14th studio release also went multi-platinum and turned out to be a lone victory for prog rock in the boom years of Blur-style Britpop and dance music.

The Division Bell should also be remembered for its music rather than the intra-band bickering that had blighted the previous nine years.

In October 1985, three years after Floyd’s The Final Cut, founder member/bass guitarist Roger Waters took out a High Court application to try to prevent the Floyd name being used again. In December, he informed the group’s record company that he was leaving the band, and that Pink Floyd were no more.

Unfortunately for Waters, David Gilmour had no intention of laying Floyd to rest. “Dave absolutely saw red, and finally got it together to go back to work,” wrote drummer Nick Mason in his memoir, Inside Out. A year later, the Waters-less Pink Floyd made their debut with A Momentary Lapse Of Reason.

Rick Wright, who’d left the group under duress in 1979, had returned midway through the sessions, but wasn’t made a full-time member again. Instead, Wright’s name topped a list of 16 session musicians and backing singers deployed to help bring the band back from the dead.

The album had an arduous birth. Gilmour worked briefly with several outside songwriters, and the process was frequently interrupted by calls from lawyers tasked with defending the band’s decision to continue. Waters even tried to stop the new Floyd from touring. But his protests failed to halt the band.

A Momentary Lapse… was denounced by Waters as “a fair forgery”, but still reached No.3 in Britain and America, and was promoted with a tour that turned Pink Floyd into the second highest grossing act of 1987. “I didn’t think it was the best Pink Floyd album ever made,” said Gilmour.

But it proved that Floyd could still be a commercial success without Waters, the man who’d devised the concepts for The Dark Side Of The Moon, Wish You Were Here and The Wall.

The first steps towards making The Division Bell began in January 1993 with Gilmour, Mason and Wright jamming at the Floyd’s own Britannia Row Studios in North London. Before long, Guy Pratt, who’d played on the Momentary Lapse… tour, joined them. It was a dream come true for the bassist who, as a teenager, had watched Floyd play The Wall at Earls Court. “It was thrilling to know you were playing on a Pink Floyd record,” said Pratt, who recalled Gilmour gently instructing him to lose “90 per cent of the notes I was playing”.

By spring, Gilmour had moved the operation to his houseboat-cum-studio, Astoria, on the Thames, and he brought in The Wall and A Momentary Lapse… co-producer Bob Ezrin. Having amassed around 65 of what Nick Mason described as “riffs, patterns and musical doodles”, “we had what we called ‘the big listen’,” explained Gilmour, “where everyone voted on each piece of music.”

Ideas were merged or discarded. But so much material was left over that the band briefly considered, then rejected, the idea of releasing some of it on a separate album, “including a set we dubbed ‘The Big Spliff’,” wrote Mason, which was, apparently “the kind of ambient mood music being adopted by bands like The Orb”.

The whittling-down process continued, but Floyd’s voting system was abandoned when the others discovered that Rick Wright was awarding his ideas the highest possible score, and everybody else’s the lowest. Part of the problem was that Wright still wasn’t a full Pink Floyd member: “It came very close to a point where I wasn’t going to do the album, because I didn’t feel that what we’d agreed was fair.”

In the end, Wright was fully reinstated, and had a credit on four of the final album’s 11 tracks.

Shortly before the summer, Floyd – joined by Guy Pratt and fellow touring Floyd musicians, guitarist Tim Renwick, percussionist Gary Wallis and keyboard player Jon Carin – entered Olympic Studios in Barnes, West London, and recorded a handful of new songs.

In autumn, they reconvened on the Astoria and began developing these songs further. But Gilmour now faced the hurdle of writing lyrics. Unlike Waters, he wasn’t a confident lyricist. Ex-Slapp Happy songwriter Anthony Moore, who’d co-written on A Momentary Lapse…, and former Dream Academy singer-songwriter Nick Laird-Clowes would both contribute to The Division Bell. But Gilmour’s then girlfriend, journalist and author Polly Samson, would end up co-writing the lion’s share of the lyrics.

“I started writing things and looking to her for an opinion, and gradually, as a writer herself and an intelligent person, she started putting her oar in and I encouraged her,” explained Gilmour, who would spend the day working on the music on the Astoria, before going home to write lyrics with his soon-to-be wife. “There was,” he said, “a whole invisible side to the process.”

Not everyone was comfortable with the situation. “It wasn’t easy at first,” admitted Bob Ezrin. “It put a strain on the boys’ club, and it was almost clichéd to have this new woman coming in and then get involved in the career. But whatever David was thinking at the time, she helped him find a way to

say it.”

Between them, the couple wrote the album’s strongest song, High Hopes. “It pulled the whole album together,” said Ezrin. “It also gave us an idea around which to hang some of the broader concepts.”

High Hopes was partly inspired by Gilmour’s childhood and adolescence in Cambridge. Its beautiful lap steel guitar solo evoked Shine On You Crazy Diamond, while composer Michael Kamen’s orchestral arrangement flashed back to the strings and woodwind he’d used on Comfortably Numb.

In the meantime, Floyd dragged some of their vintage keyboards out of storage and sampled their sounds on Take It Back and Marooned. Rick Wright was delighted: “My influence can be heard on tracks like Marooned. Those were the kind of things that I gave the Floyd in the past and it was good that they were now getting used again.”

In fact, the whole album was full of familiar motifs. Dark Side… and Wish You Were Here saxophonist Dick Parry returned to the fold. But so too did Dark Side… mixing supervisor Chris Thomas, who helped oversee the final mix instead of Bob Ezrin. “That was disappointing,” understated the producer.

On the final album, High Hopes’ themes of nostalgia and reflection were reprised in the Gilmour/Samson/Laird-Clowes composition Poles Apart. Its first verse was apparently inspired by Syd Barrett; its second by Roger Waters. What Bob Ezrin called “the broader concept” of The Division Bell was communication and the difficulties thereof: between friends, wives and lovers, and former bandmates.

The clues were there in titles such as Lost For Words and Keep Talking, the last of which sampled scientist Stephen Hawking’s voice. “It’s more of a wish that all problems can be solved through discussion than a belief,” said Gilmour, who was well aware of the irony considering Pink Floyd’s poor track record in communicating with each other.

However, The Division Bell also seemed to have a subtext: rebirth. On Wearing The Inside Out, Rick Wright cast himself as a man venturing back into the world after years of isolation. “There’s a lot of emotional honesty there,” said Ezrin. “Fans pick up on a sad and vulnerable side of Rick.”

Wright wasn’t the only one being emotionally honest. Gilmour talked about ‘killing the past’ on Coming Back To Life. Many took this as a reference to embracing his relationship with Polly Samson (whom he’d marry in July ’94) and rejecting the hedonistic lifestyle he’d been enjoying for the past few years.

Revisiting The Division Bell now, you can hear a lot of angst and tension. On What Do You Want From Me, supposedly inspired by good old fashioned marital strife, Gilmour sounds fired up and frustrated and dishes out some heavy blues guitar. Play it alongside his last solo release, 2006’s charming if very contented-sounding On An Island, and you can hear the difference.

By New Year, the album was complete, and the band began casting around for titles. Nick Mason favoured ‘Down To Earth’; others preferred ‘Pow-Wow’. In the end, The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy author and friend of the Floyd, Douglas Adams, spotted the words ‘The Division Bell’ in the lyrics to High Hopes, and suggested that instead.

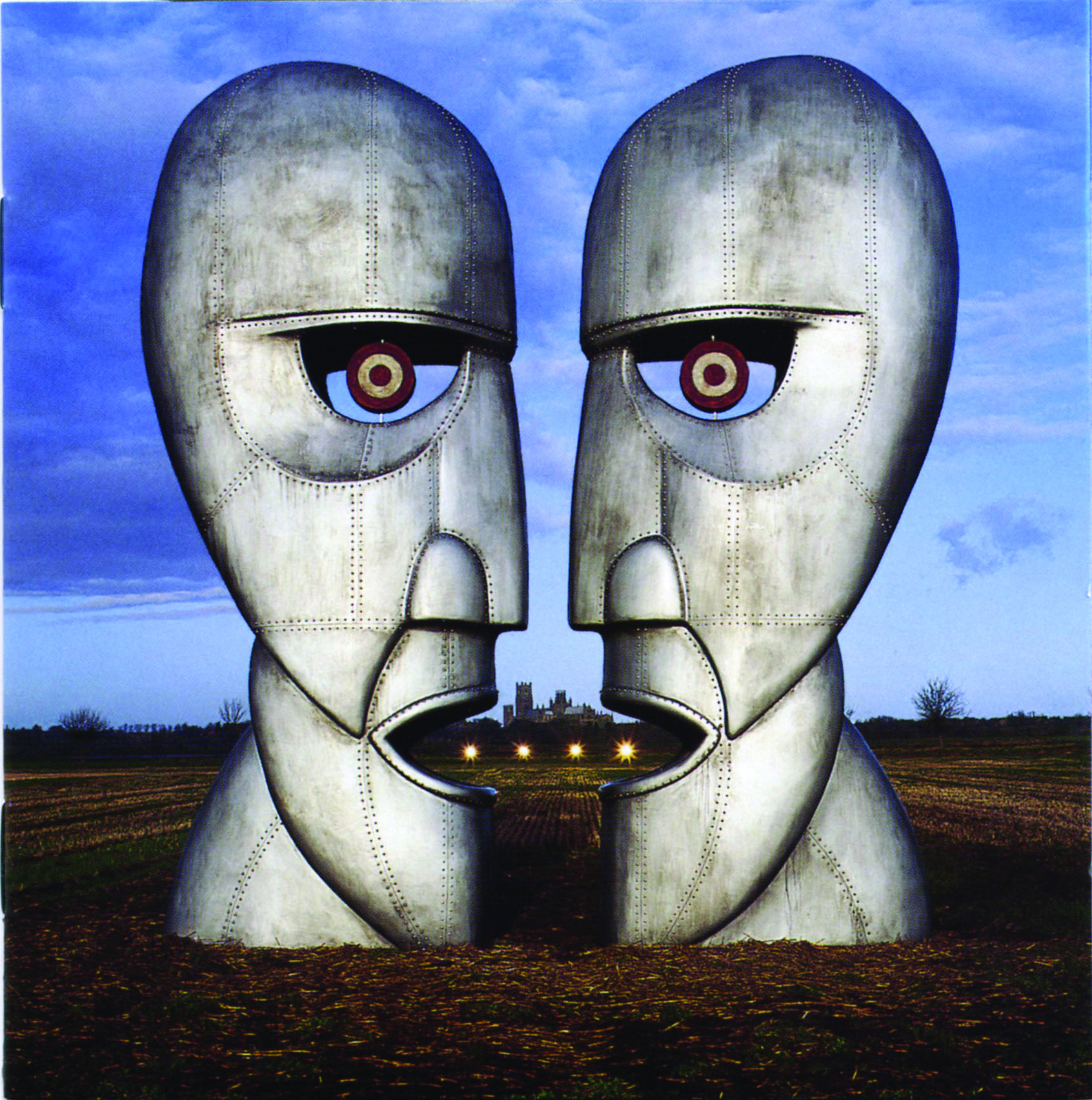

Although The Division Bell suffers from what Guy Pratt calls some “80s production hangovers”, it’s compensated for by Gilmour’s lack of contentment and complacency, and Rick Wright’s welcome presence. Unlike A Momentary Lapse…, The Division Bell felt like a group effort, and Gilmour was soon telling interviewers that he thought it was the most Pink Floyd-sounding album since Wish You Were Here. Everything, from those spaced-out keyboards to the languid guitar solos via Storm Thorgerson’s grandiose cover art, compounded his theory.

Roger Waters called it “an awful record” and Melody Maker likened it to “chewing on a bucket of gravel”, but Floyd’s fanbase disagreed and the album soon topped the charts in 10 countries worldwide. Although the Floyd had sounded adrift on A Momentary Lapse…, there was an assuredness about The Division Bell that boded well for the future.

Naturally, you can’t help wondering what a follow-up might have sounded like. Bob Ezrin feels the same. “I wish it wasn’t the last Pink Floyd album,” he said. “But I wouldn’t hold my breath.”

27 years on, The Division Bell remains a fine swansong, and a fine album. Nobody, including Blur, or even Roger Waters, can take that away.

This article originally appeared in issue 46 of Prog Magazine.