Few stories bring together Y Viva España, progressive jazz, children’s television, underground folk and psych, and some of the most collectible records on the UK scene. Peter Eden’s does. Although Eden’s profile on Discogs is rather impressive – “Musician, manager, songwriter, A&R man, producer, arranger, publisher, editor, record company owner” – he is one of the most elusive and under-the-radar of all the managers we’ve spoken to.

Eden hasn’t worked in the music business directly since the 70s, and is a man who redefines the term ‘unassuming’. People with a quarter of his experience have written books and performed one-man shows, yet Eden enjoys his retirement by the seaside in the town where he was born, delighted by and often amazed at the ongoing interest in his work.

Eden came to attention as Donovan’s co-manager at the very start of both of their careers, and that was enough to set him off on a long and varied journey. He was born in Hadleigh, near Southend-On-Sea, in Essex, 73 years ago, and his teenage years coincided with the rise of skiffle. “Skiffle was the start of it all. Everybody was in a group. You saw Lonnie Donegan and you thought you could do it yourself. It was something fresh and new. Through that you became interested in folk music, blues, jazz.”

Eden spent his time in bands as a drummer. Initially, he was in the New Deal Skiffle Group with Colin Davidson and David Elvin, whom Eden would later produce as part of the Jubilee Lovelies. As rock’n’roll took hold, the group became the Colin Dale Combo (“We liked ‘combo’ as it sounded American”), and they then became The Problems.

“We went professional when The Beatles came along because you could make some money from it,” Eden recalls. “We did backing for Billie Davis, Susan Singer and Mike Sarne. We were driving up and down the A-roads, playing anywhere.”

When the group split, Eden was asked by Rodney Saxon to help out at his Studio Club in Westcliff, a suburb of Southend, to offer advice on bookings. Eden began running a proto-fanzine, Spotlite, as well as looking after bands. “I was managing The Cops’n’Robbers, a great, inspirational R&B band. Their singer, Brian ‘Smudger’ Smith was a bit more than just another blues singer.”

In conversation with them one day, Eden mentioned that there was a need for a British Bob Dylan. Smith told him they knew of just the person and would bring him down the following week. Seven days later, Donovan Leitch, a troubadour from Glasgow via Hertfordshire, arrived, fresh from a year busking around the UK. Donovan played in between the Cops’n’Robbers sets and was an immediate hit.

“He had really good songs,” Eden says. “At that time I was green – I didn’t know how to manage people. I knew Geoff Stephens, the songwriter, who lived nearby. I told him I’d found someone I thought was unique. Well, not unique – he couldn’t be, he was just like Bob Dylan – but someone you could work with.”

Eden and Donovan got on well, with the singer staying at Eden’s flat. “Geoff suggested we manage him together, and I handle the production side of things. A producer – that sounded good. Not that I knew what it was!”

And so Eden’s career as A&R man/manager/producer began in earnest.

After the success of Donovan locally, the duo knew they had to go nationwide to break their artist. “I joked that he should be on Ready Steady Go! – Geoff knew people there. They wanted to have something that was fresh, something they had found. The producers said they would sign him and he would be on the show for three weeks. You have to give it to Donovan, he did do it very well.”

After the first recording in early 1965, Eden and Stephens travelled home on the train that Friday night. “I thought it hadn’t worked. When we got to our office on Monday, Rediffusion rang to ask us to collect all the mail they’d received. We both realised it had happened. He was all over the papers: ‘Who was the greatest – Dylan or Donovan?’ It was a lovely story. It exploded beyond anything we could think of.”

Pye Records chased a deal, and by late Spring, Catch The Wind was No.4 in the charts, and Donovan’s debut album, What’s Bin Did And What’s Bin Hid, was in the Top Three.

“I suggested to Don we get an electric guitar. Through Cops’n’Robbers, we’d done some electric stuff. I went to America with him and we were doing Shindig. Somebody asked us if we’d heard Dylan’s new track – he’d gone electric. It was Like A Rolling Stone.”

However, after producing Donovan’s second album, Fairytale, Eden and Stephens were to part company with their singer. “Somebody said he was paying too much for his managers, the deal he had wasn’t good. On reflection, you can see things in a different way. Don was affected by a lot of friends – nobody had wanted to know him, but then he was successful and everybody began coming out of the woodwork. That’s showbusiness.”

You get a sense with Eden that very little has gone to waste, though. “I was sad because I’d put a lot of work into it, but then it introduced me to producing a record. Geoff taught me about publishing, got me into the music industry and it went on from there. Suddenly I had a living. I could produce and manage. I had ideas.”

Eden worked with Pye, EMI and Decca on a variety of projects, advising artists. “I worked with Mick Softley, the Fingers, Bill Fay, the Jubilee Lovelies and Bob Davenport. EMI did a thing called Independent Producers – I worked with Tim Rice and Mark Wirtz.”

Eden saw Pink Floyd early, as he knew them through John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins and Bryan Morrison. He was one of those who’d mentioned them to EMI. He looked after the Crocheted Doughnut Ring, signed to Deram, but it was in the field of jazz that he really found his appetite. “John Surman had been voted the world’s No.1 baritone saxophonist. He was such a lovely guy. I got a deal for him with Decca.”

Through meeting Surman, Eden met and worked with Michael Gibbs and Alan Skidmore. Eden knew there had to be a way to get jazz to cross over into the new progressive underground. “Jazz was a dirty word – it was always filed in with Acker Bilk,” he sighs. “I said, ‘Sell this as progressive music, because it is – it’s exciting, it’s better than a lot of the prog groups out there.’”

His paymasters weren’t so enthusiastic. “Decca didn’t really get the idea, so that’s why I went to Dawn, because I’d produced Mike Cooper, [who recorded] basically a straight blues album. [Music executive] Peter Prince went from Motown to Pye and he asked me and [producer] Barry Murray to look after this label.”

After two highly collectible albums on Deram, Surman came over to Dawn as part of the Trio, with bassist Barre Phillips and drummer Stu Martin. Eden advised Surman to play colleges instead of jazz clubs and a new audience was born. “Then Soft Machine went jazz and it started to take off. It was such esoteric music, and it was selling.”

But it was Eden’s next move for which he’s most remembered – the setting up of the independent Turtle Records, the stuff of prog jazz legend. Releasing just three albums in 1970 and 1971 (Outback by Mike Osbourne, Flight by Howard Riley, and Pause, And Think Again by John Taylor), the label was a masterclass in homespun prog and free-form jazz esoterica.

“We were having trouble with companies so I decided I would have Turtle as my own label.”

Eden soon realised how difficult his previous companies’ salespeople had it now he was on the frontline himself – huge shops would only stock a couple of copies of the albums. Mike Osbourne began selling them at his shows, making more money that way.

“I paid for it all – I could do anything I wanted. My wife Glyn and I would sit at home packaging records and sending them out. I loved it. ECM later did something similar – Turtle was the beginning. I did a John Taylor album because I thought he was brilliant.”

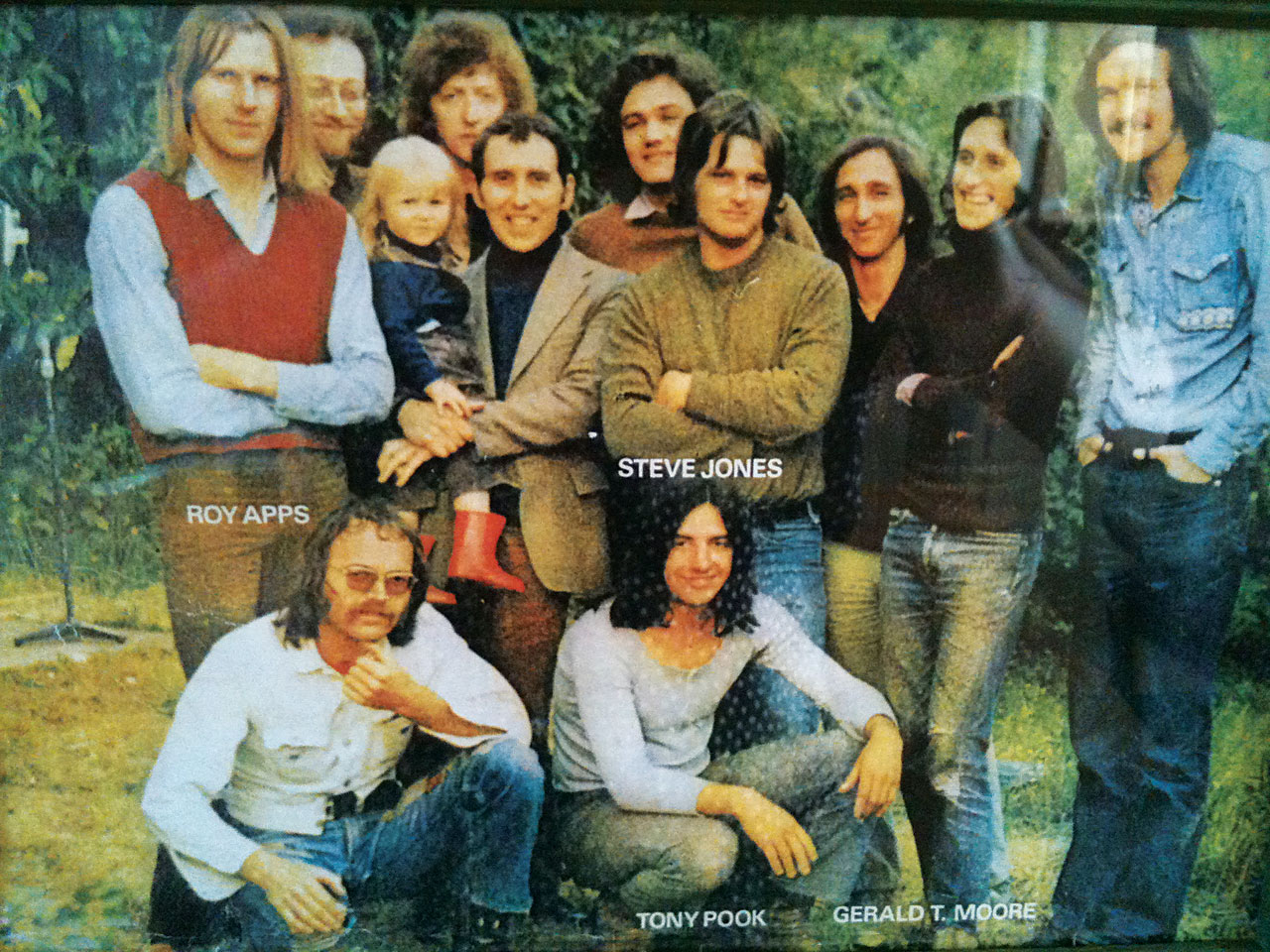

Eden struck up a relationship with the band Heron, one of his final management engagements. Like most of his work, they would simply not be pigeonholed – a roots group doing soul covers? “We did This Old Heart Of Mine and people would say, ‘Why is there a Motown track on a folk album?’”

Their guitarist GT Moore branched out, and his act, the Reggae Guitars, signed to Charisma. Working with Moore led to a few encounters with Charisma owner Tony Stratton Smith, and Eden recalls Smith putting Vivian Stanshall (with whom Eden had been at college in Southend) in his place when he kept boisterously interrupting them while drinking in Soho.

However, the opportunity to run his own record shop in Southend was too great a lure and Eden began scaling down his music business connections. He kept working with companies such as Sonet, whose founder, Rod Buckle, had known him for years. Sonet had long-standing connections with the Nordic countries, and one of Eden’s proggiest odysseys was producing Finnish band Tasavallan Presidentti.

Eden produced the group’s final album, Milky Way Moses, recorded in London in 1974. It was all going well until Eden heard the lyrics, which were a straight English translation of the Finnish. Eden offered to rewrite them, the band objected, and when the album was released, the critics savaged their words.

Eden played a part in another Sonet classic, the British translation of Y Viva España, recorded by Swedish singer Sylvia Vrethammar. “Sylvia was lovely – she hated the record but had to sing it all over the world. I used the same backing track for a single by Andrew Sachs, playing Manuel [from Fawlty Towers]. We wrote Manuel’s Good Food Guide the B-side, too.”

One of his final ventures was as lucrative as anything he’d done. Animal Kwackers was a children’s TV series featuring men dressed in animal costumes being a band – not far from The Banana Splits, but this band were beamed down from a spaceship and played Beatles covers (as well as Do The Kwack, which could actually pass as rare groove). They featured Rory, a lion; Twang, a monkey; Bongo, a dog; and Boots, a tiger. Eden wrote and produced the songs and the stories, often with Heron guitarist Roy Apps, who was instrumental in the TV show’s inception – although he isn’t necessarily aware of that fact.

“Roy rang me up in the middle of the night when I was managing Heron, said he was stuck in Spain and could I send him some money. I thought, ‘I love the music, but this is not my job.’ So I started to think of something you could do that wouldn’t involve artists. Animal Kwackers was born.”

Working with ex-NEMS man Bernard Lee, the series was sold to Yorkshire TV, spawned three series (in the second, Eden played Bongo, the drummer), four albums and a DVD.

But Eden’s record shop was where his heart lay, and, by the end of the 70s, was what he was doing full-time.

“I was finding out what people in the street were really liking. I put lots of local Southend bands together and did a rockabilly collection [The Best Of British Rockabilly, Vol. 1 – Anything They Can Bop, We Can Bop Better!] in 1978, and it sold.”

Eden can look back on a life well lived. “I was never really an agent, never a producer, nor a manager in the sense that I wanted to look after an artist’s career. I just wanted to get them going. Funnily enough, Heron have just been asked to go to Japan. You want to build a reputation and always be needed.”

And on that note, Peter Eden, one of music’s invisible men, happily disappears again.

THE SPIRIT OF EDEN

Five of his favourite recordings.

**1. Donovan:** Sunny Goodge Street (from Fairytale, Pye, 1965)2. Bill Fay: Be Not So Fearful (from Bill Fay, Deram, 1970)

3. John Surman: Dance (from John Surman, Deram, 1969)

4. Heron: This Old Heart Of Mine (from Twice As Nice & Half The Price, Dawn, 1971)

5: Michael Gibbs. Family Joy, Oh Boy! (from Michael Gibbs, Deram, 1970)

PETER’S PEAK PERFORMANCES

Eden picks his favourite live shows.

1. The Mike Westbrook Concert Band featuring George Khan on tenor sax, Essex University, 1970.

2. GT Moore And The Reggae Guitars, Kursaal, Southend- On-Sea, November 1975 (supporting Dr Feelgood on the Malpractice tour).

3. Michael Gibbs, Leicester Square, London, circa 1970.

4. Jubilee Lovelies, The Barge, Battlesbridge, Essex, Saturday nights in 1959⁄1960.

5. Lonnie Donegan, The Tavistock Hotel, London, March 1957. “It was a huge room filled with young lads with guitars and washboards. We strummed along to Lost John with Lonnie and his group, learning the chords and lyrics!”

The managers that built prog: Peter Jenner

The Managers That Built Prog: Andy Farrow

The Managers That Built Prog: Gail Colson - the woman behind Peter Gabriel