So you think you know all about the Moody Blues? Well, have you heard the story about the band member who got so out of it one night with Keith Moon that he ended up having a conversation with a legendary cartoon character? Or about the Moody who was one of the last people to see Jimi Hendrix alive? Or the one about the fabled bunch of groupies with whom the band hung out? Maybe, just maybe, there’s another side to this band of hugely successful, highly talented musicians, the one that belies the perception of them as workaday, colourless musicians who somehow drifted through a glittering career. As one of their albums almost had it, the Moody Blues have lived through some strange times.

“In December 1973 we played two shows at Madison Square Garden on the same day,” says vocalist/guitarist Justin Hayward, as he begins the process of debunking the claim that the Moodies are the beige men of prog. “Between the first show at 4pm and the second four hours later, Ray Thomas and I went for a walk outside the venue. There were loads of fans around, but nobody recognised us.”

“Both the shows were sold out, and a lot of fans were left without tickets,” continues flautist/vocalist Ray Thomas. “I saw one tout there really scalping the fans. So I went up, paid about $400 for a pair of tickets and told him to piss off. Then I found two fans who were without tickets and gave them the ones I’d just bought.”

“The thing is, they still didn’t recognise us!” laughs Hayward. “Ray didn’t take anything for the tickets. He was happy to know that they were in the audience and would realise who gave them those precious tickets.”

This was the day The Moodies brought Manhattan to a standstill, and were still faceless enough to wander around without security.

“We were always very good at keeping a low profile,” says bassist/vocalist John Lodge. “In the early 1970s, we had our own plane, The Starship [not the infamous Zeppelin aircraft of the same name], to fly around on tour, but the only people allowed to travel on it were ourselves and those who worked for us. It was really luxurious, a Boeing 707 we’d had converted. There were bedrooms, a lounge area and a dancefloor. We even had an organist we’d hired to play all the time on flights. Very rock star.”

“I tell you how decadent it was,” laughs drummer Graeme Edge. “We had the world’s longest running blackjack game happening on that plane. We played it all over the world, with all sorts of currencies on the table. Who won in the end? It was our manager Jerry Weintraub. I wouldn’t say he cheated, but he was the only sober one at the table!”

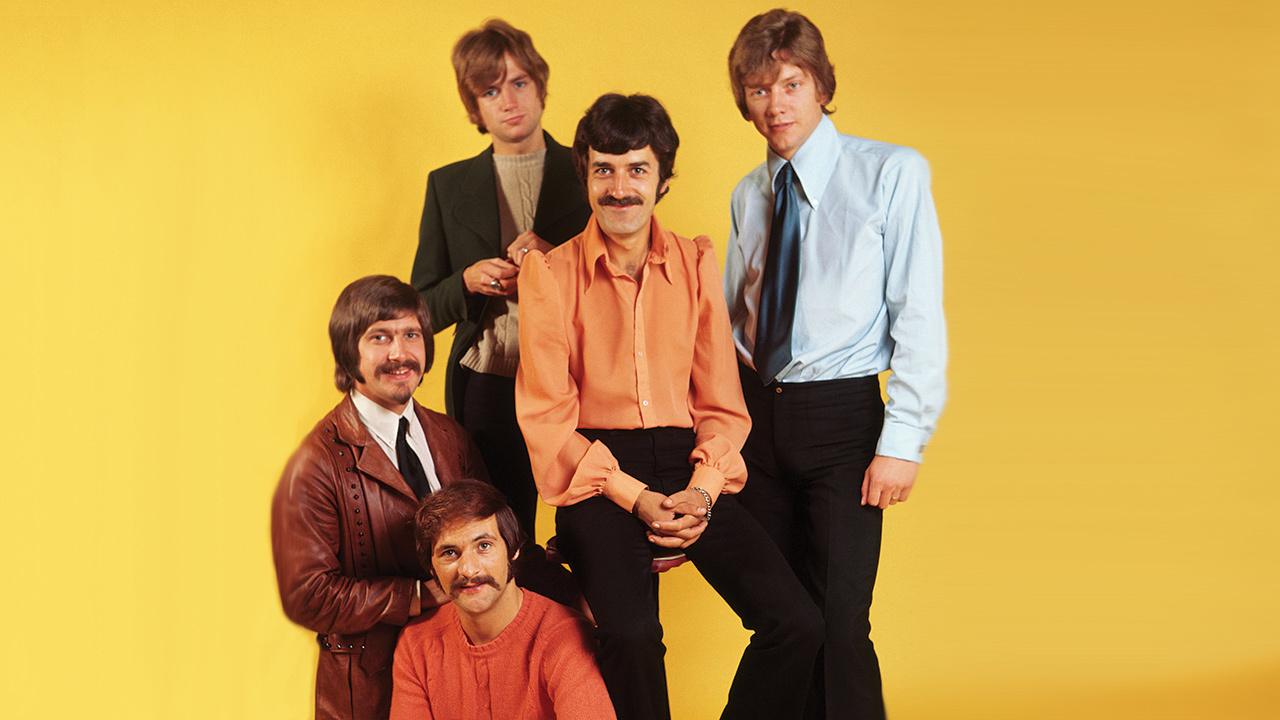

This was a far cry from the days when Lodge and Hayward joined the band in 1966, teaming up with Thomas, Edge and keyboard player Mike Pinder. In fact, when the line-up initially got together, it appeared they had no sort of a future.

“The first shows we did together were in Belgium,” says Hayward. “It was about the only place where there was still a demand for the band. When we got back to England, it looked like we had no future. We were getting dwindling crowds and decreasing money. It all came to a head when we did a show in Stockton during March 1967. We were so bad, a fan accosted us afterwards and told us we were the worst band he’d ever seen, and we’d ruined the night for him and his wife who’d paid £12 for a night out and had seen the dreadful Moody Blues!

“On the way back in the van, Graeme – who was asleep lying over the equipment at the back – suddenly woke up and said quietly, ‘That guy was right. We are rubbish!’. It was the moment we ditched the R&B covers, got rid of our Moody Blues suits and decided to stand or fall by our own songs. What did we have to lose?”

So, the band that had started in 1964 playing R&B and had a Number One hit with their version of Go Now, decided to go in a different direction.

“We took on board Justin’s folk influences,” recalls Edge. “And began to evolve a style that was much more in that vein.”

The real turning point for the band came when Pinder brought in a weird and wonderful new musical addition.

“I used to work for Streetly Electronics in Birmingham, who developed the Mellotron,” recalls Pinder. “So I knew what it was capable of doing. Anyway, I found out that the Dunlop Factory in the city had a Mellotron they’d bought for dances, but nobody there knew how to play it. So I went down there, offered them £20 for it, and that’s when it became part of the Moodies’ new style.”

That line-up’s first album, 1967’s Days Of Future Passed, was supposed to be a version of Dvorak’s New World Symphony, designed to demonstrate Decca Records’ Deramic Stereo System, but instead, and without the knowledge of the label bosses, they recorded their own songs. Collaborating with Peter Knight, the man who had been assigned the job of arranging the orchestral interludes that were supposed to be part of the new version of the New World Symphony.

“Decca didn’t know what to make of the album,” admits Thomas. “There was nothing else like it. Was it classical? Was it progressive? Was it rock? They weren’t going to release it until the American label said they got what we were doing and wanted to put it out.”

Against all expectations, Days Of Future Passed reached Number 27 on the UK chart and sold over 100,000 copies. The Moodies were reborn and bigger than ever.

In those days there was a real sense of camaraderie between bands, one that was reflected in the surprisingly close relationship the Moody Blues had with the Beatles.

“We were really friendly with John Lennon and George Harrison,” says Thomas. “They were always round at the house in Roehampton, where we all lived. I recall one particular day when they came over, and played us their new album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. We were so blown away by what they’d done. When we did Days..., we invited John and George over to hear what we’d recorded. They were really complimentary about the album, it meant a lot.”

Thomas is as equally delighted by the time spent in the company of the colourful and vibrant if wilfully unpredictable, Keith Moon.

“We were at a club called The Scotch Of Saint James in Central London. There was a public loo across the road, and usually it was a lot easier to go there than use the one in the club. On one occasion, Keith and I went out to use the facilities. Keith was holding a giant spliff, and boldly went up to a policeman and asked for a light – he was really polite about it too. But there’s me shitting myself that we’re about to be arrested! He got away with it, but it taught me never to trust Moonie, ha ha!”

“Keith turned up one night at a club looking really dirty,” says Edge. “He’d been locked in by his wife after being out on a five-day bender. So, what did he do? He jumped out of the window into a passing rubbish truck.

“Anyway, he sent out his roadie to pick up 10 pills, gave five to me and kept five for himself. Now this was 2am, so I thought I’d be clever and took one, while palming the other four. Keith had all five of his. We kept on drinking until seven in the morning, so by the time I got home I was in a right old state. My wife and daughter were still asleep, but I found a Bugs Bunny doll my daughter had, one where if you pull the string it says, ‘What’s Up, Doc?’ I had great fun for ages, talking to Bugs and getting him to answer, ‘What’s Up, Doc?’ to everything. Moonie was dangerous!”

Pinder, meanwhile, had the chance to party with Jimi Hendrix. But the night had a dramatic conclusion.

“This was at a club called the Bag O’ Nails, where all the bands would hang out after gigs. I was introduced to Hendrix, and we got on really well, because of a shared interest in UFOs. We were drinking very heavily, and about 1am I decided to leave. But he stayed on.

“As I left we agreed to meet the next day. But I woke up to headlines that he’d died overnight – I must have been one of the last people to see him alive.”

Edge, though, can go one better when it comes to Hendrix. He got to play with the young guitarist at the Scotch.

“There were three raised tables in that place, and each was reserved,” he says. “There was one for The Animals, which had a sign saying, ‘Don’t Feed The Animals’. There was one for the Beatles, with the sign saying, ‘No Insecticide’, and one for us saying, ‘Please, No Blues’. Anyone could sit at these tables. But if us, The Animals or the Beatles turned up, then the relevant table was ours. Mind you, we usually asked whoever was sitting there to stay where they were and get us drinks!

“The house band would usually stop about 2am, but the club stayed open and musicians would then get up and jam. One night, I was on drums with Jack Bruce on bass and Eric Clapton on guitar when into the club walked Chas Chandler, The Animals bassist, with this kid from Seattle called Jimi Hendrix. The next thing you know, Hendrix plugs in and plays with us! The pity of it all is that there was no footage or recording of the night, just so I can show people how great I was with Hendrix!”

Despite becoming familiar faces in and around Soho’s boozy haunts, they continued to create and develop as a band. In 1968 they released In Search Of The Lost Chord, which Hayward believes was a crucial album for them.

“This was when I feel we found our soul and direction. It was when everything gelled musically.”

In 1968, the band travelled to what was then Czechoslovakia to headline a show in Prague. Their timing couldn’t have been any less prescient if they’d been Spinal Tap.

“Of course,” says Lodge, “it was a time of social change and upheaval, but it was during the era when Alexander Dubcek was in power, and everything had become a lot more relaxed. You heard rock’n’roll music at the airport, and it didn’t feel you were in an Iron Curtain country at all.

“So we went and did the gig, came back to the hotel and the manager said he wanted an urgent word with us. He explained that the Russians had invaded the city and had taken over the hotel and we had to move. ‘Hang on,’ we said. ‘We were here first and we’ve given you the Thomas Cook vouchers to pay for our rooms, we’re not going anywhere!’ But we soon came to our senses, and moved out. We ended up sharing a hotel room somewhere else. That’s five members of the band and a roadie, all crammed in.

“Eventually, the only way we could get out of the country was to sneak onto

a Pakistan Airlines Red Crescent flight, which is like being on a Red Cross mission. We arrived in the country as rock stars and left in the back of a Red Crescent emergency aid plane – that was a reality check.”

By 1972, the band had released seven studio albums, which not only helped define a musical Zeitgeist but would set a blueprint for symphonic rock. In the process the band scored three number one albums in the UK and one – 1972’s Seventh Sojourn – in the States.

It was the sort of success that could only be matched by a singularly exalted excess that comes from being the kind of band who might tour in their own plane.

“Oh, we all dabbled in all sorts of things,” Hayward says readily. “Well, all of us apart from John. He never participated. Usually, they were the more psychedelic type of drugs. I must admit we always had a great time on acid. And those trips inspired a lot of our music at the time. Come on, I’m not exactly giving away secrets here. Anyone who listens to what we wrote and recorded will immediately know we’d been on acid.

“Talking of which, we got very friendly with Jefferson Airplane in those days. We toured together and took part in their love-ins. They’d use the back of a truck and drape a tent over it, and that would be where all the fun happened. So, we certainly knew how to have a good time on the road.”

Another person who became a close friend of the Moodies was Timothy Leary, the American psychologist famed for advocating the use of psychedelic drugs. Once described by Ronald Reagan as the most dangerous man in America, Leary coined the phrase ‘Turn on, tune in, drop out’, which became a mantra for much of the hippy movement during the late 60s.

“We got on really well with him,” says Thomas. “We spent a lot of time at his house. He was a great guy, like a mischievous Irishman. And had a very good sense of humour. Timothy was always great company. I wrote the song Legend Of A Mind (from In Search Of The Lost Chord) about him and the way he used the Tibetan Book Of The Dead. It was really tongue-in-cheek. But he once told me that he was more famous for being the subject of a Moody Blues piss take than for anything else he’d ever done – and then added that if I ever repeated that to anyone then he’d totally deny it! Well, Timothy’s now been dead for over 15 years, so I reckon it’s okay to tell that story!”

But it wasn’t just drugs which got the Moody Blues’ attention in America. There were also the girls…

“In those days, it was very expensive for fans to travel everywhere to see any band,” reveals Hayward. “Just about the only people who could do that were the groupies. And we had some who would be at a lot of our shows on tour. Did we ever indulge in activities with them? Well, come on. We were young guys from England, in a successful band and these girls were offering us their services... what do you think happened? Of course we enjoyed ourselves with some of them!

“There were also the girls you came across in a lot of the cities. You knew they were there for whatever band was in town. But that was the way it worked. It was us one week, and then they’d move on to somebody else, Led Zeppelin or whoever, the next week. But it was a mutually beneficial arrangement. They’d look after you, no strings attached.”

And then there were the groupies made infamous by their exploits with Frank Zappa and Hendrix, the Plaster Casters celebrated their conquests by capturing the moment in a dental mould making substance called alginate, which doesn’t scan quite as well as plaster.

“Well, yes, we did meet them,” says Hayward. “But I certainly did not have a plaster cast made of any part of my anatomy. As far as I can remember, only one of us actually had it done. I would never think of naming him in public. But he now lives in California, and his initials are ‘MP’!”

“Justin said that, did he?” says Pinder, “Well, I would never want to contradict what he says. Can I confirm it? Ah, that would be telling. Maybe it’s best to leave others to decide whether that story is true. And I have no idea how my member might measure up against the others in their celebrated collection.”

But not every encounter with an attractive girl would conclude with some sort of happy ending, as Thomas recalls.

“In those days we roomed together. I shacked up with Graeme, while Justin and John shared. Anyway, one morning, John was in the bathroom washing his hair, and there was a knock at the door. Justin opened it to find himself face-to-face with this beautiful, young girl. She had on a fur coat, and that was all. So, she opened her coat and said to Justin, ‘Do you wanna have a ball?’

“You know what Justin said to her? ‘Oh, I can’t. John’s in the bathroom doing his hair’! What a thing to say. He later admitted he wasn’t sure why he’d said that, but it was the first thing to come into his head.”

To replace Pinder, the band turned to one-time Yes and Refugee keyboard player Patrick Moraz.

“There’s no doubt that Patrick was a fabulous musician,” says Hayward. “I’d say that he was a brilliant addition from that viewpoint. But he was also very difficult to deal with. It was the era when superstar keyboard players were starting to emerge, challenging the more traditional guitar heroes. And that might give you some idea of the problems we had working with him. But there’s no doubting the ability and ideas he brought to the band in the studio and onstage.”

“I loved the Moody Blues and what they did,” says Moraz. “For me, it was a great combination of progressive ideas and melody, which is where I was most at home. I look back on my years with the band as being nothing but an absolute pleasure.

“And I was also lucky enough not to have the problem of trying to come to terms with the huge stature of the Moodies. After all, I was used to playing the biggest venues in the world with Yes, and having people like the American President coming to gigs, because he was a fan!”

“Yes might have attracted the US President,” retorts Thomas. “But we had James Bond as a fan – Pierce Brosnan, that is.”

What Moraz brought to the band was a more contemporary feel. A lively, instinctive player, Moraz gave the Moodies a sense of revitalised colour. So much so that they strode purposefully into the 1980s, ready for

a host of new musical challenges. All four studio albums on which he features as the sole keyboard player were Top 30 successes in the UK, while 1981’s Long Distance Voyager made it to the top of the US chart.

“Things had changed so much by the 80s that bands no longer had complete control of their albums,” sighs Hayward. “You had so many people at record companies who wanted to tell you their ideas for everything. The only album from that period where we were totally in charge was …Voyager. I insisted on using the picture on the cover, and refused to budge despite a lot of label pressure. I’m glad I stuck to my guns though, because the artwork is superb.”

The Moodies parted with Moraz as they were working on 1991’s Keys To The Kingdom album (which is why he’s only featured on a handful of tracks), and it was a split that still rankles with Moraz.

“People often ask me why I left the band. The truth is that the band left me. I really don’t want to dig up the past and relive what happened. I’d rather recall the good times and the great music.”

Now down to a core of four, the band suffered another disappointment in 2002 when Thomas decided that for him too, it was time to retire.

“I’d been having health problems for a few years. Particularly with keeping my balance and it reached a point where I knew that, sooner or later, I would inevitably take a tumble onstage because of the problem. So, it was time to get out.

“Realistically, what did I have left to prove? I had played more than once at every great venue around the world, apart from Sydney Opera House. I had appeared on

a whole catalogue of great albums, of which I’m still intensely proud. And I’d also been in one of the biggest party bands of the late 60s/early 70s. When we all lived together in one house, we were legendary for our parties. These didn’t start until midnight, and ended... well, when everybody had passed out!”

Thomas’ health had proven to be an issue as far back as 1988’s Sur La Mer album, which is one of the reasons why he’s not featured at all. However, producer Tony Visconti also felt his voice and flute didn’t fit the more modern direction into which he was helping to take the band.

Since his departure, Hayward, Lodge and Edge have kept the Moodies moving forward, with a hectic touring schedule that sees the band still playing to crowds that remain as enthusiastic and enthralled as they’ve ever been. And, as Edge insists, none of them have any intention of stopping.

“Why should we? I look at someone like Chuck Berry. He did such a long tour celebrating his 75th birthday in 2001 that it ended when he was 76! And he’s still playing live a decade later. I’m just 71, so a mere kid compared to him.

“Somebody once told me that his biggest regret was deciding to retire. I won’t be making the same mistake. As long as I can actually get onstage and people still want to see us play, to see the Moody Blues, then we’ll carry on.”

On May 4 2014, the Moody Blues will celebrate their 50th anniversary. But Edge feels it’s something of a false anniversary.

“For me, the real one is when Days Of Future Passed was released, because that’s when the true Moody Blues were born. That’s when we found our voice and became the band everyone knows us for being. But it’s still incredible to think we actually did that album 46 years ago.”

“I am so pleased John, Justin and Graeme are still out there, keeping the Moody Blues name alive,” says Thomas now. “They do it all with my full blessing.”

So, what would the band like to be remembered for?

“For playing a club called The Psychedelic Playground in Philadelphia,” laughs Lodge.

“They didn’t have seats or chairs. Just coffins set at a 45-degree angle. You simply lay in them and listened to the band play. It goes to show that we have played in the most weird and wonderful venues in the world.”

“And we’ve also had some very weird fans,” concludes Hayward. “One guy in Texas spent weeks standing virtually naked on a street corner telling everyone we were the true messiahs, and that we would ultimately save the world with our music. Then he met us, changed his mind and told everyone we were false messiahs. You can’t make it up!”

This article originally appeared in Prog Magazine issue 34.