“The old man was thin and gaunt with deep wrinkles in the back of his neck… Everything about him was old except his eyes and they were the same colour as the sea and were cheerful and undefeated.”– The Old Man And The Sea, Ernest Hemingway

It is almost 3pm. The storm that met us in the Cancun Channel has passed and the passengers are disembarking into the island port of Cozumel. A long line of dudes with beards and black T-shirts stretches down the dockside where Mexicans dressed as ancient Mayans, psychedelic mariachi bands and gay pirates prepare to separate them from their money with salty cocktails and fancy shitnaks.

The old man in the naval captain’s hat in Penthouse 1, a deluxe suite that overlooks the deck of the Carnival Ecstasy, couldn’t care less. He’s not going to Mexico (“I’ve been,” he shrugs). The blinds are drawn, the ship is still for the first time in three days, and the man sips a glass of rosé wine and thinks of an old friend of his who went by the name of Daniels.

“I can’t drink Jack now,” he says. “I don’t like the taste of it any more. I came out the hospital with a set of different tastes in me. I drink vodka now. Only now and again. More social. I don’t drink at home hardly. Just wine mostly. I don’t smoke at home, but I’ll smoke a few cigarettes out here because you meet people who still smoke and, fuck it, you know? Does smoking affect my singing? My singing depends on it, man.”

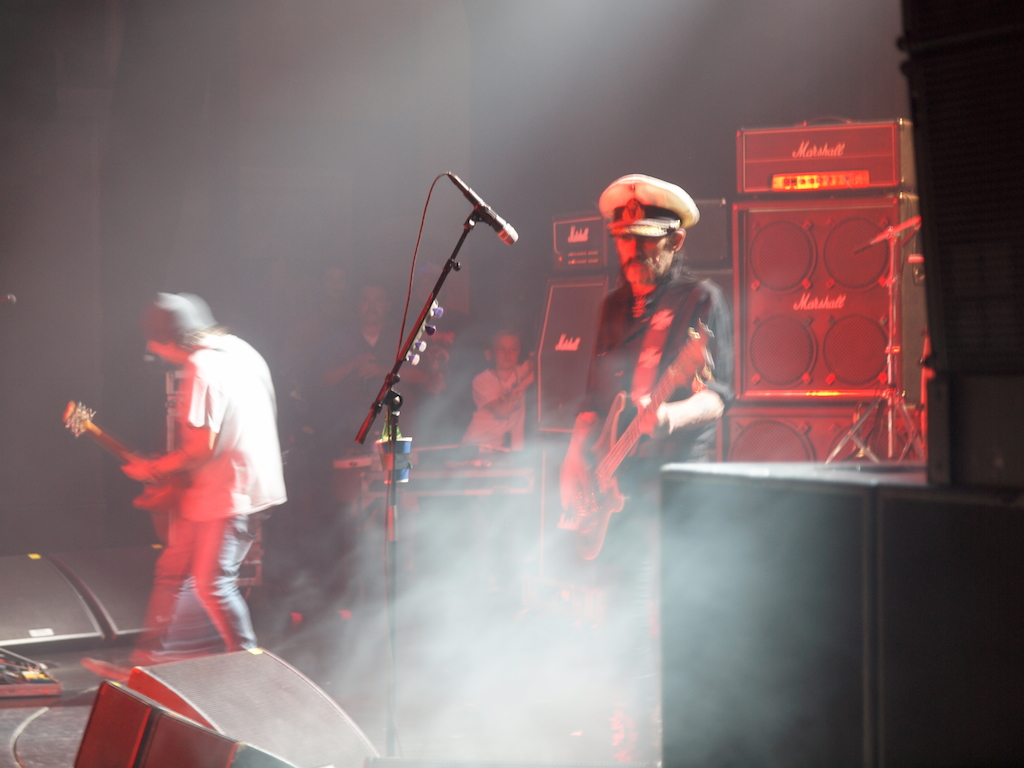

You could say there are two captains on the Carnival Ecstasy. There’s the man responsible for navigating the Gulf of Mexico, docking the ship and running the crew – Pierluigi Barrile, Italian born and the youngest captain in the Carnival fleet – and then there’s our guy, the old man in Penthouse 1, who not only has the hat, he’s the reason 1,500 or so people have come from all over the world to fill this boat and wear his uniform: the one with the badge that says ‘Motörhead, England’. Today, this is his fucking boat.

The old captain, Lemmy (a man who can’t swim and doesn’t even have a driver’s licence), has been keeping the young captain up at night. “I didn’t go into the main lounge where Motörhead were playing,” says Barrile. “It was too noisy.” He adds that he’s “heard of Motörhead but not heard them”. Well, not really: “I could hear them from my cabin,” he says. “I’m at the back of the boat so the speakers are right under – everything vibrates!”

But for now the cabin is still. Almost exactly 10 years ago, in what was my first official assignment as a Classic Rock staffer, I interviewed Lemmy in a hotel room in London. Back then, within minutes he had poured me the first of many half pints of Jack Daniel’s with a dash of Coke (“Well, you don’t want it diluted too much, do ya?”) and offered me drugs off the end of a knife. Today, Lemmy sips wine and offers me a beer.

I ask him the same question I asked Mikkey Dee earlier and will ask Phil Campbell days later: how would he sum up the last year in Motörhead?

“Pretty good actually,” says Lemmy. “Apart from the illness I had. But that’s not Motörhead, that’s me. Motörhead’s been going from strength to strength.”

“It’s been good,” says Campbell. “We’re just finding our feet again. Lem’s a lot healthier now, the album’s done really good for us and there’s more work on the table than we can handle. If we’re turning down work all the time it can’t be too bad.”

And Mikkey? How would he sum up the past year? Mikkey doesn’t hesitate: “A fucking mess,” he says.

The Motörhead Motörboat is the latest in a long flotilla of band-branded cruises: the Mötley Cruise, the Kiss Kruise, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Simple Man cruise, not to mention generic rock cruises like Shiprocked and 70,000 Tons Of Metal. If it feels like a new phenomenon, it’s not – the Silja Rock cruise from Stockholm to Helsinki has been running for 25 years. But it’s become a novel money-maker for bands (it’s rumoured that Kiss got $4 million for their last one) and an intense alcoholiday for fans.

Motörboat is scheduled to go from Miami to Key West and then to Cozumel – an island off the Yacutan Peninsula, south Mexico – and back, with a bill that includes Anthrax, Zakk Wylde, Down, Testament, Danko Jones and many more, each playing two gigs over four days. So Classic Rock is here to write about this (the rumours are that it could be a total Motörmess, with underwhelming ticket sales and Megadeth cancelling at the 11th hour) and about the ‘fucking mess’ that was Motörhead’s last year.

That mess, says Mikkey, is what you get when you live as fast as Motörhead. “If you drive a car at 250 kilometres an hour and you do any jerky moments on the steering wheel, you will flip that car,” he says. “If you’re driving at 50 kilometres, no problem – you can swerve any way you want. The same thing goes with Motörhead. We have such a tough schedule – or have had – and we live at 250 kilometres. In a normal fucking band, yeah, they run into a few health problems: unfortunate, sad, not too bad, you can deal with it. When it happens to us, it’s such a huge disaster immediately. Health problems, yes, no big deal – but the effect is huge.”

Motörhead’s appearance at Wacken, summer 2013, came to an early close with Lemmy unable to continue due to a combination of intense heat and bad health. In video of the festival he looks pale and uncomfortable and two songs in he tells the crowd: “I’ve just been in hospital but I’m getting better now – ha! – so I thought we’d come along and see if we could completely fucking cripple ourselves playing for you fuckers.” He almost did.

Motörhead’s traditional November tour was cancelled and rescheduled for February. Then the rescheduled shows were cancelled too. “I made them cancel [the November tour],” manager Todd Singerman told Decibel. “Lemmy didn’t wanna cancel. But what was gonna go down is what happened in Europe over the summer. See, he fucked up in Europe. He was supposed to rest for three months, and he refused. He ended up doing that show [at Wacken], which he wasn’t supposed to do, and it ended up being 105 degrees out there.

“He’s got a really bad diabetic problem,” he went on. “He probably sneaks Jack and Coke here and there. He’s been trying to substitute it with wine, and I’m sure he’s slowed down on the speed. He thinks wine’s better than Jack, but it’s still got tons of sugar, you know? He doesn’t grasp that he’s just trading one demon for the other. That was the compromise with the doctors, by the way – trade the Jack for the wine. But he doesn’t tell them he’s drinking two fucking bottles, either. These are the battles we’re up against. Keep in mind, he’s been doing all this stuff on a daily basis since Hendrix. And it’s coming to roost.”

With two tours cancelled, says Mikkey, “…All hell broke loose. We went out officially and said: ‘Look, we can’t apologise because there’s nothing to apologise for.’ I mean, if you get sick, if your wife gets sick, you don’t go out and apologise. I don’t want to fucking apologise if I’m sick – I can’t help it. You don’t go to a guy in a wheelchair and give him a fucking bollocking, you know what I mean? There is nothing to apologise for. You have feelings for the fans that actually lost some money, but apologise? I don’t know.”

Album number 21, Aftershock, certainly needed no apology. Possibly the strongest album of the five-album purple patch they’ve enjoyed since hooking up with producer Cameron Webb, it boasted bruised psychedelic blues and raw quasi-ballads alongside the usual gang of flick-knife-fast rockers, with Phil Campbell letting a particularly feral pack of riffs off the leash. There were moments where Lemmy sounded wounded, but mostly he sounded as defiant as ever.

“I was surprised how good it came out because I was sick as a dog when I was doing it,” says Lemmy. “I had no strength at all. I was shuffling to the mic out of the control room. I had to sit down to sing a couple of them. It’s incredible that it came out that good. Lucky, lucky, lucky, again.”

He was in and out of hospitals for months. One hospital, says Phil, voted him their ‘worst patient in living memory’. “He was giving the nurses hell,” he says. “He wasn’t lying in bed – he was sitting up, reading his book, grunting and groaning, demanding this and that. ‘Why can’t I go out for a fucking fag? I’m paying so much a night for this fucking hospital, if I want a glass of wine, fucking bring it in! Where’s my rosé?’ All this business.”

Out of the hospital, he moved out of his famous porn-and-nazi-memorabilia-filled flat off Sunset and into a new place with a long-term on-and-off-girlfriend. Slash was a regular visitor. His return to the stage was planned carefully. Key gigs this summer included Coachella, Hyde Park and Wacken. “One of the best things was when I came back and found out I could still do it,” he says. “Because I had serious doubts, y’know. But we did Wacken – paid back. So that was a good thing. I couldn’t have come offstage even if it was the worst agony I’d ever had because I had to repay it.”

The days of the punishing tour schedule are over. This month, Motörhead’s annual UK jaunt has been reduced to three UK gigs. “I’ve got to slow down a bit,” says Lemmy. “I remember on the seventy-nine tour with Saxon, we did fifty-three gigs in fifty-six days. You know, that’s out of the question. I can’t do that no more. You get tired easier. I mean, old age sucks, man. Don’t ever get to it. I don’t recommend it.”

People worry about him. They see him on stage, thinner – looking vulnerable for the first time in his career – and they think: “He oughta slow down, take it easy! Who’s making him do this?” The answer, of course, is no one. It’s what he does. “I’ll be there till I drop dead,” he says. “What am I going to do otherwise? I’m qualified to be a single parent, that’s about it. I didn’t make my GCSEs.”

“You can’t force him into doing anything,” says Campbell. “He likes doing it – his life is on the road, he’s always said that. And it always will be. He’s skinnier than he was, but that’ll build back up. As soon as he said he was ready to do it, we put all the options in front of him. You can’t force him to do anything – he’d just say ‘Fuck you’ and that’s it.

“He’s going to be a bit slower but he’s enjoying it. Nobody’s bloody perfect. And he sounds great. He’s not going to be the same as he was thirty years ago with what he’s been through. He can have a bit of my weight! A bit of mine and Mikkey’s – they could call us the Liposuction Brothers!”

For a while it looks like the Motörhead Motörboat might be another mess to add to Mikkey Dee’s shitlist. Our first stop at Key West is abandoned due to severe weather. Megadeth were scheduled to appear but just 12 days before the ship was due to depart, Dave Mustaine cancelled due to illness. Their name is still on the official cruise T-shirts – but misspelled as ‘Megadeath’.

The VIP restaurant – where the band, crew and media are eating – is a classy affair with a dress code: “Cruise Elegant – shorts, T-shirts, jeans, flip-flops… are not allowed in the dining room.”

This week it’s dress-code carnage. There’s dudes in wife-beaters, tattooed metal chicks in bikinis, Midwestern moms in ‘Metal As Fuck’ T-shirts, waiters tripping over facial hair and a distinct air of not giving a fuck. But contrary to what you might expect, the staff have nothing but praise for the levels of politeness shown by a bunch of guys that look like they’ve just stepped out of a Hollywood prison yard. I try to prompt a reaction from several crew members – “What do you think of this lot, eh? Bet this is a shock to the system!” – but no one bites.

I catch one crew member, dressed in nautical whites, singing along to Anthrax soundchecking, visibly excited: “Proper music!” she says. Apparently having 1,500 bearded, bandana-wearing growlers on board is a walk in the park compared to the EDM cruises they regularly do.

The boat is a blast. They’re going to do it again and you should go. Think Hard Rock Hell with hot tubs, on the high seas, with a hard-on. The schedule gets back on track. There are Black Sabbath yoga, beer and bingo sessions run by the bands, and a belly flop competition judged by Chris Broderick and David Ellefson of Megadeth (who’ve come as part of Metal Allegiance – a metal covers band who are joined by Phil Anselmo, Joey Belladonna, Chuck Billy, Mike Portnoy and more). Each gig has a celebratory holiday atmosphere. Anthrax are on fire. Down are fun. And Motörhead? Well Motörhead are…

In Penthouse 1, Lemmy has another glass of rosé. Some bands, I tell him, get in keyboard players or second guitarists that just so happen to be able to sing a bit like the frontman. For a bit of backup, like. Ever consider that?

“No,” he says. “Nobody plays bass like me and nobody sings like me. Nobody wants to, you know.”

At the Hyde Park gig in the summer, people were saying that there were loads of solos in the set to give him a break.

“No. The reason that the solos came so close to each other was that we only had 40 fucking minutes to play. Mikkey has always had a drum solo. He’s good enough to do it. We never gave Phil Taylor a drum solo, or Pete Gill, but with Mikkey you just have to own up: he’s that good.”

I could see Lemmy behind the amps during a drum solo the night before: his face wasn’t in an oxygen mask.

“No. I’m not Bon Scott. I remember going to see him with a bird I really fancied. We were backstage and he’d come off for his oxygen all the time. He was really fucked. It caught up with him quicker. He was more of a drinker than me, I think. I don’t actually drink a lot but I can out-drink people. I don’t get drunk any more. I’m immune. I just like the taste, you know?”

In conversation, Lemmy jumps all over the place. He revisits stories he’s told before and goes off on all sorts of interesting tangents. He mentions his old sparring partner (and former Classic Rock writer) Mick Farren, who died on stage last year. “Somebody told me his last words were ‘Tell Lemmy I’m sorry’ but I don’t believe them,” he says. The two fell out over an article Farren wrote about Lemmy’s predilection for Nazi memorabilia.

“Steve Sparks – who was one of the contemporaries of Mick – wrote a letter to him saying, ‘You fucking arsehole! I remember you putting on an SS uniform to get onstage at The Roundhouse – what the fuck are you talking about?’ But there you go. He’s dead and I’m not.”

New York writer Legs McNeil is also on the Lemmy shitlist for a similar transgression.

He tells a story about Keith Moon rushing into The Speakeasy naked one night and sticking his cock in John Lennon’s dinner. “Yoko went ‘ffrmmm!’ [rushing noise] out the fucking door. John said: ‘Fucking hell, Keith,’ and he said: ‘It was the only way I could think to get you on your own, old boy!’ Fucking great days they were.”

At one point I ask if he thinks that being single all his life has given him an edge. “Yeah, definitely,” he says. “My crew and the band is my family. I live with a great girl, she’s my family too. But the crew and the band are where I am, even when I’m off the road. I believe you should treat the crew how you would like them to treat you. A lot of bands treat the crew like dirt and I don’t understand it. You depend on them to make you sound good and look good, right? How can you treat them like shit?

“They do half of your job. Some of our guys have been with us 20 years. Tim’s been with me nearly 30, with a couple of breaks here and there. He keeps getting married, you know, but he always comes back after he gets divorced.”

To his real family, I say. “He knows where he lives,” says Lemmy. “This way of life ruins you for everything else. It’s like, you’re on the road and you’re free, they can’t catch you. You’re in one place and then you’re in another place, several hundred miles away, so you’re in and gone before they catch you. It’s a community in the bus and on the road. You’ll never find anything like that again. It’s like being in the marines – it’s that camaraderie.”

Ernest Hemingway fished on these seas. I have packed just one book to read on this trip: the last book he finished, The Old Man And The Sea, a novella about an ageing fisherman called Santiago and his attempt to end an 84-day dry spell in which he hasn’t caught a fish. Alone on the sea, the old man hooks the biggest marlin he’s ever seen but in trying to land it, he’s dragged far out into the Gulf. When he finally kills the fish, it’s too big to get in his boat. He ties it to the side and on the way back to shore is beset by sharks attracted by the scent of the dead fish. They devour the marlin. By the time Santiago gets home, weakened by his days at sea, there is nothing left of the fish but its head, tail and skeleton.

The Old Man And The Sea is often interpreted as Hemingway’s reaction to the critical mauling handed out to his previous novel, and, maybe it’s cabin fever, but I start finding parallels with Lemmy. The old man, cheerful and undefeated: still gigging, making some of the best albums of his career, while the sharks nip away at his reputation. The Mick Farrens, Legs McNeils and Hawkwinds of old, the journalists and the bloggers of today, the doctors and the well-wishers telling him to slow down, the assholes that have been saying he’s too old for a decade now – each taking a chunk out of all he’s worked for.

And still he goes on, determined to ‘land the fish’: to record a better album than the one before, to keep on killing ’em live, keep his family on the road.

Because the point of The Old Man And The Sea is not that human struggle is futile – it’s that it’s all we have. “Man is not made for defeat,” Santiago tells himself. “A man can be destroyed but not defeated.“.

“So, how is Lemmy? How were Motörhead?” Those are the questions I’ve been asked over and over since I got back. “How’s he looking? What was the gig like?” And it’s hard to answer. In person, he’s funny and warm, earthy, wise – great company. Cheerful and undefeated. Live? The shows were good. You couldn’t fault the delivery. Phil works the stage a bit more. Mikkey is the madman centre stage and the powerhouse driving them. Musically, it’s solid. At the end of the first gig, Lemmy’s voice was strained, but by the second it was fine.

The difference is in the performance. Lemmy is thinner. Where he used to look invincible, now he looks vulnerable. He never used to move much on stage, but he had an easy confidence about him. Bass players talk of the importance of ‘pushing air’ – the physical effect that amplified bass notes can have – and there was a time that every molecule of Lemmy pushed air. His presence alone seemed to guarantee a good time.

So it’s hard to watch. That’s old age for you. We can choose not to witness it or we can accept it. It’s where we’re all headed. We are the generation that will be in the old folks’ home listening to Anarchy In The UK and Ace Of Spades, with faded tattoos and Ramones T-shirts. There’s nothing we can do about that, and nothing we can do about Lemmy. Except respect and wish him well.

Think about it. This is a guy whose father left when he was three months old. Reunited with him in his twenties, Lemmy told him to go fuck himself. At school he was the only English kid in 700 Welsh. He fought every day: break time, lunch time, on the way home. Sacked by Hawkwind, he went home, fucked all their wives and formed a band more commercially successful.

He said fuck you to his father. He said fuck you to religion. He said: “Fuck god, fuck the devil, and fuck the church too. I’m responsible for my actions, I don’t have to hide behind that. The devil didn’t make me do it – I did it, whatever I did.”

He said fuck you to politicians, fuck you to their laws, fuck you to all the doctors. He’s just a fuck you kinda guy.

Telling a Fuck You Guy what to do – how do you think that’s going to work out? And even if you could force him to change? Just because you got the power, it doesn’t mean you got the right.

On the other hand, he can’t do this forever. Unless…

Idea for a movie: a cruise ship full of metalheads is blown off course in a tropical storm and docks at the nearest island off Mexico. The guests go ashore to party, welcomed by the locals – mariachi bands, gay pirates, Mayan warriors – the usual shit. Tequila is pounded, beer chugged. Motörhead take to the stage in the bar and play Going To Mexico. But… Midnight signals the arrival of The Day Of The Dead and the locals turn into zombies. They descend on the metalheads. There is carnage – limb-tearing, beard-eating, eyeballs in margaritas. Motörhead are onstage playing throughout it all. They haven’t noticed. Lemmy maybe cocks an eyebrow.

The metalheads retreat back to the boat and set sail. Phew. Except the kitchen staff have turned zombie. Limbs bob in hot tubs. Zombies strip the tattooed flesh from the metalheads and wear it over their own rotting skin. People jump off the boat. But there are sharks. Zombies jump off the boat after them. Now there are zombie sharks.

While all this is kicking off, in the main hall, Motörhead are on stage. Cornered in the venue, there’s a massive metalhead versus zombies showdown. Mikkey Dee is beheading zombies with cymbals. Phil Campbell plays a solo so gnarly it makes zombie eyes explode from their sockets. Lemmy just stands there and shakes his head a bit. Well, that’s what he does.

A plucky hero – I dunno, a journalist let’s say – works out how to kill the zombies and rescue the band. But… Lemmy has been bitten. He turns into a zombie. Luckily, instead of an appetite for human flesh, all he craves is Marlboro Reds, Jack Daniel’s and amphetamine.

Motörhead’s tour schedule remains unaffected. Dates are added. Meet And Greets become Sight And Bites, as fans queue up to get shit signed and be gnawed as Lemmy creates an undead audience across the world. The band’s new album, Born To Ooze, Undead To Win, becomes their biggest hit.

And everyone dies happily ever after.

For more information on 2015’s Motörboat Cruise, visit www.motorheadcruise.com