What do Pink Floyd, Gustav Holst, The Beatles, Serge Gainsbourg and Swedish hair metal types Europe have in common? The answer: Laibach. Since their inception in 1980, the Slovenian band’s vast body of work has included a selection of cover versions as disparate as they are unlikely, from a German language version of Queen’s One Vision to a deadpan take on Live Is Life, the naff 80s hit by Austrian pop quartet, Opus.

They’ve even devoted entire albums to the stuff. 1988’s Let It Be refashioned The Beatles’ last LP as a Wagnerian blowout, complete with choirs, martial rhythms and mad guitar solos. The following year’s Sympathy For The Devil deconstructed the old Stones’ classic in a variety of puzzling ways, while NATO (1994) was an international covers project based around the theme of war. Most intriguingly, from a philosophical standpoint, Laibach insist that they don’t treat these endeavours as covers at all, but rather revisions of history.

“We treat pop culture as historic material that can be reinterpreted the same way as classic theatre works by Shakespeare, Molière, Chekhov or Brecht usually are,” explains Laibach’s Ivo Saliger via email, the evasive group’s preferred method of communication. “Some of the pop songs are hiding within themselves a completely different content if they’re approached from a different point of view. And that’s what we most often do: we dig out the Hidden Reverse.”

It’s an ambiguous tactic in keeping with Laibach’s MO. Provocateurs at heart, they fuse experimental and industrial rock with neo-classical and pop art. They call it Gesamtkunstwerk, a multi-disciplinary practice with music, installations, performance, graphics, paintings and video.

Central to all this is their use of visuals. Laibach have enjoyed toying with taboos throughout their career, from appropriating the symbolic imagery of Fascism and state power to live shows in which political film footage is intercut with vintage pornography. They’ve been accused of having affiliations to both the far left and far right, which is a good indicator of how much their work is open to interpretation. Throughout everything, Laibach have refused to directly counter any criticism of them as extremists, merely stating that they’re fascists “as much as Hitler was an artist”.

What people often miss about Laibach is their humour. They’re big on irony, magnifying the ridiculous – be it crap Euro disco or totalitarian symbols of oppression – so that they take on an entirely new context. Poker face is their default setting, which only adds to the confusion about whether or not they’re joking. On one occasion, at a press conference in France in the late 80s, Laibach listed their influences as Tito, Toto and Tati. When Prog asks about what drew Laibach to Live Is Life, Saliger replies: “The pure simplicity of the philosophical content of the song about life as such. And the unbearable Austrian accent of the singer.”

If there’s one recurring theme in Laibach’s music, it’s identity – national and cultural. This is understandable as they formed amid a period of political unrest in Yugoslavia, following the death of the long-serving authoritarian, President Tito. The void was filled by a power struggle between new liberals and nationalist hard-liners, while Laibach’s choice of name – the German translation of Ljubljana – was a reminder of Slovenia’s wartime past under Nazi occupation.

“Given that we originally came from the Eastern European hemisphere, cemented with a communist background and the traditional inferiority complex towards Western pop culture, we were forced to deal with the idea of cultural identity all the time,” says Saliger, whose name is a pseudonym of Laibach’s oldest active member. “Political turmoil in Yugoslavia was partly the result of the cultural frustration that this country had to face, being too open to Western influences from the 1950s onwards. The situation hasn’t really changed much today. The major cultural ideological and colonialist trends are still dominantly imposed over the region, and the entire Eastern hemisphere, from the West.” Saliger adds that the effect of all this has been to transform local identity “into a kind of distorted copy of itself, gloriously culminating every year at creep-show events like Eurovision or ‘turbo-folk’ reality TV shows. Authentic cultural identity in the East is as much alive and existing as a dead poets society.”

Laibach’s subversive approach to authority has often landed them in trouble. The Yugoslavian government refused to allow them the use of their name in the 80s, so the band started to advertise themselves using a black cross, a product of their involvement with local art collective, NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst). Subject to police raids, censorship and even a lawsuit from the Catholic church, Laibach are nothing if not resilient.

1983’s The Occupied Europe Tour exposed them to a wider audience, especially in Britain. And John Peel’s championing of the band on nighttime radio eventually led to a deal with influential indie label Mute, for 1987’s Opus Dei. When pushed on Laibach’s musical signposts, Saliger reverts to type and gives an elliptical response, citing people like Tesla, Duchamp and Magritte as equally influential. And what about prog? “Of the well known progressive acts we liked Sweet, Slade, T. Rex, Sparks, Suzi Quatro, David Essex…” he says with a straight bat, before adding, “And Yes, Deep Purple, The Nice, ELP and King Crimson.”

As befits a band whose creative life has been so open to misunderstanding and cultural translation, Laibach tend to do things that others don’t. In 2015, they were invited to play two gigs in North Korea. The occasion, part of the 70th anniversary celebrations of the end of Japanese colonial rule, meant they became the first foreign rock group to perform in the country. It was a painstaking process – subject to suspicion, state interference and mounds of red tape – chronicled in the 2016 documentary, Liberation Day.

“We just didn’t know until the very end if it was really going to happen, because every day new mysterious officials arrived at the venue to see the preparations and rehearsals,” Saliger recalls. “And most of them didn’t seem to be satisfied with what they saw and heard. Nevertheless, we believed in good faith that all would be just fine in the end.” The biggest surprise, he says, is that the gigs actually went ahead, “despite the North Korean Committee For Cultural Relations With Foreign Countries receiving warnings about the ‘subversive’ nature of Laibach”.

The band’s setlist in Pyongyang was bizarre, even by Laibach standards. Alongside One Vision, Life Is Life, Across The Universe and Europe’s The Final Countdown, they tackled the patriotic North Korean anthem, We Will Go To Mount Paektu, but later dropped it from the set after North Korea censored it at the last minute. It’s a cultural exchange that reached full fruition with several numbers from The Sound Of Music.

The enduring tone of Laibach’s trip was conciliatory. Their decision to play South Korea earlier this year made them the only act to have performed in both countries. “Koreans in an ideologically divided country are, with all their differences and similarities and their difficult history, an ideal audience for Laibach,” Saliger declares.

“Symbolically, it was very important that we were able to perform in both Koreas. When we first did the show in North Korea, there was a lot of criticism of us from the South. And when we later performed almost the same material in South Korea, we were advised by North Koreans not to do it and also not to show Liberation Day at the South Korean film festival. In spite of all the pressure though, everything went well. South Koreans loved the film and concert and [director] Morten Traavik recently visited North Korea again, where he’s preparing new, demanding cultural activities.”

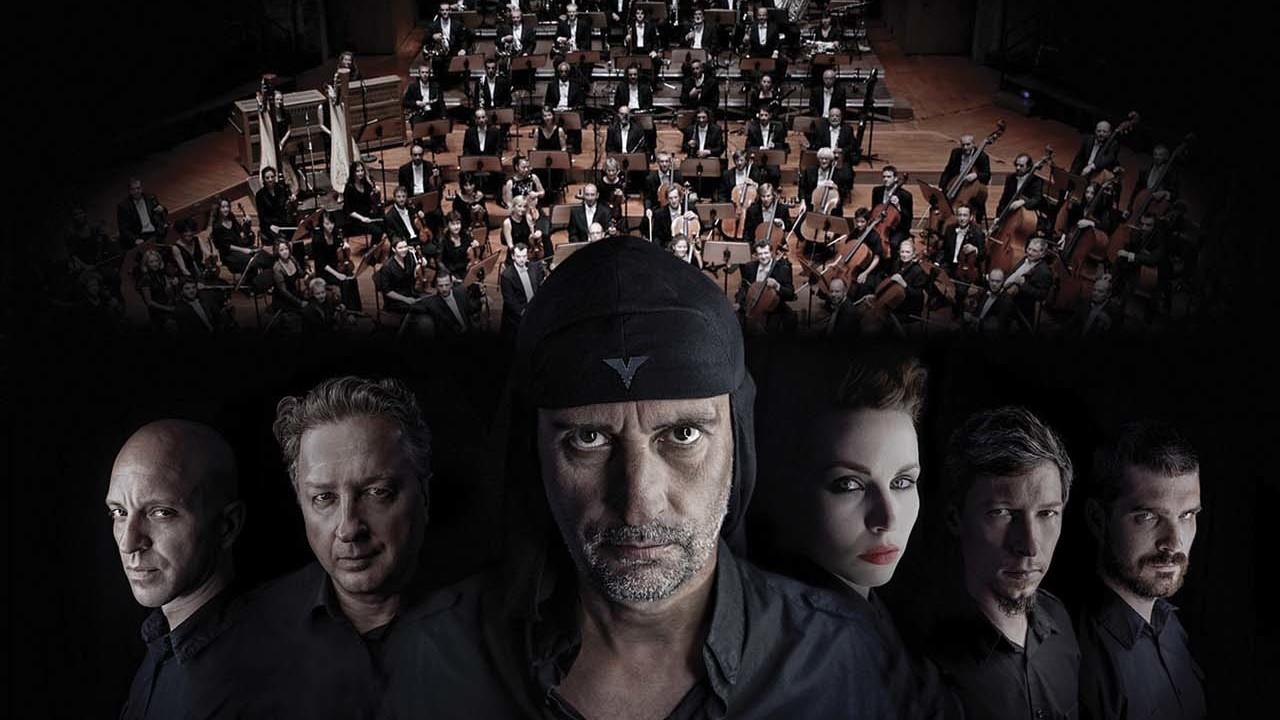

In the wake of these achievements, Laibach have just issued a new album, Also Sprach Zarathustra. Originally conceived for a theatrical production of Friedrich Nietzsche’s titular novel in Novo Mesto, Slovenia, in March 2016, Saliger explains that, “We later recomposed and modified the mainly fragmented music into 12 tracks.” The album, which also features the Slovenia Symphony Orchestra, is more stately and foreboding than its techno-flavoured predecessor of 2014, Spectre.

The tension is heightened by chilly atmospherics and found noise – clangs, gongs, engines in overdrive, the sound of knives being sharpened. All of which stays true to the heaviness of Nietzsche’s philosophical text about the death of God, the ‘Übermensch’ and the theory of an infinitely recurring universe. “We first and foremost see …Zarathustra as a deeply moral, anti-nihilist, contemplative and religious work,” states Saliger. “So we’ve approached it as such and created the songs as psalms. Regarding the death of God, Nietzsche may have killed him, her or it, but only to establish a new, better and modern one. God is dead, long live Übergod!”

The album’s contrasting moods, from restful prog to abrasive industrial rock, are illustrated by its two closing tracks, that translate to Before Sunrise and Of The Three Transformations. The difference between them, Saliger explains, “is the difference between physics and metaphysics. Physics is the mathematical perspective of the universe, and therefore tranquil and rational. Metaphysics, on the other hand, deals with philosophical questions of time and space, life and death, being and not-being…” It’s also a fitting assessment of Laibach’s multi-faceted approach to their own art.

Nations divided. Ideologies at war. Global friction between East and West, North and South. Laibach are operating in the same political climate they were born into. In their own way, they may offer a few solutions. Or at least when it comes to the EU and plotting a route through Brexit. “Laibach will certainly do what we can to steer Europe towards its future and also to keep Britain tidy,” says Saliger. “And if Britain will ever again change its mind – well, we wish it good luck! If nothing else, it’s always warmly welcomed to join our own NSK State.”

Also Sprach Zarathustra is out now via Mute. See www.laibach.org for more info.

“Laibach are many things, a consequence of their association with NSK. Musically you could stick a boot-load of labels on them: industrial, avant-garde, experimantal, to name but three. There is, however, a huge divide between Laibach’s experimental music and prog, a gap which they probably came closest to crossing with NATO, their 1994 album of war-related covers. At the end of the day though, prog they aren’t.” - Clive Summerfield

“Slovenian protest prog.” - Marc Hughes

“I think, at a fundamental level, it boils down to what separates experimental rock from prog. That distinction is murky (consider Frank Zappa for instance), but, in the case of Laibach, I think they lie deep within experimental rock territory. The music they produce is often atonal and alien, and the industrial/avant-garde classical mix that they often play is unparalleled by any other band.” - Harrison Coombes

“Yes. Definitely progressive. A mix of experimental, classical and with occasional vocal stirrings…” - J Lo Sanchez

“The Macbeth album qualifies…” - Eric Prentice

“Borderline prog. Well, borderline music, period! But they are all over the place in so many ways.” - PerPer Lundberg

“Not sure what describes them, but they are not my scene at all.” - Kevin Braithwaite

“I’d agree about Macbeth. It’s brilliant. The Jesus Christ Superstars album verges on prog at times, but also sounds like Europe at other points. Generally I’d say Laibach are more industrial/metal/goth-ish. As an aside, I’d say that Rammstein pinched a lot of their sound from Laibach and are a poor imitation of Laibach’s heavier moments…” - Richard Johnson

“Very, very industrial, but I’m afraid not prog. Listen to their new release to get a true sense of the band. I think it’s great.” - Anthony Williams

“Certainly not. However, they are interesting. My label for them would be industrial/art rock.” - Peter Brouwer

“I’m getting fed up now.” - Steve Harrison

“Amazing production on Kapital.” - Vladimir Titti

“Not prog in any way, shape or form, more like a genre all of their own. Laibach is Laibach.” - Karl-Talbot Jamieson

“They were never previously prog, but are now, by association, as you have included them in your magazine.” - Chris Bembridge

“Just Laibach and enjoy them.” - Solent Area Prog