This article originally appeared in Prog 76.

If there’s any such thing as a modern Renaissance Man, then Ryuichi Sakamoto was probably it. The legendary Japanese polymath has been at it for five decades, either as a composer, musician, producer, actor, writer, activist or conductor. From his pioneering days with proto-techno outfit Yellow Magic Orchestra and the invention of ‘Neo Geo’ (a fusionist’s paradise of global rhythms and styles) to operas and Oscar-winning film soundtracks, Sakamoto has amassed a body of work as varied as it is vast.

In 2017, aged 65, he seems to have come full circle. “I was 18 years old in 1970 and was at a very big point in my life,” he explains to Prog, down the line from his base of operations in New York. “I entered university and thought that music was at a dead end, so I knew I had to develop something totally new. I started ethnic music and electronic music, which was a big turning point for me. And I feel I’m now back in that place, very much connected to my youth.”

Sakamoto is feeling particularly energised by a new solo album, async, his first in eight years. “One of the most important themes of this album was to make music that is not dependent on one single leading tempo, so each part has its own cycle of time,” he says. “Looking at almost all music from across the world – including tribal, modern and orchestral music – it’s based on one single tempo. Apart from the famous piece by [György] Ligeti – Poème Symphonique [1962], which uses 100 metronomes, each with its own different time – I don’t know of any other music like that. So I decided I would try to make it. That was my dream for the last few years.”

async carries the distinctive hallmarks of Sakamoto’s best work. It’s experimental, strange, seductive and occasionally forbidding. In it you’ll find ambient passages, musique concrète, warm draughts of electronica, spoken‑word samples, strings, ruptures of industrial noise and more.

Thematically, it messes about with asynchronism, quantum physics and pure chaos, taking up a position on the porous line between the artificial and the organic. As 21st century concepts go, it really couldn’t be more prog.

“One of the other main themes of this album is making soundtracks for a non‑existent Andrei Tarkovsky film,” Sakamoto says, directing Prog to walker, a key track that combines the sound of footsteps, birdsong and water with a humming drone.

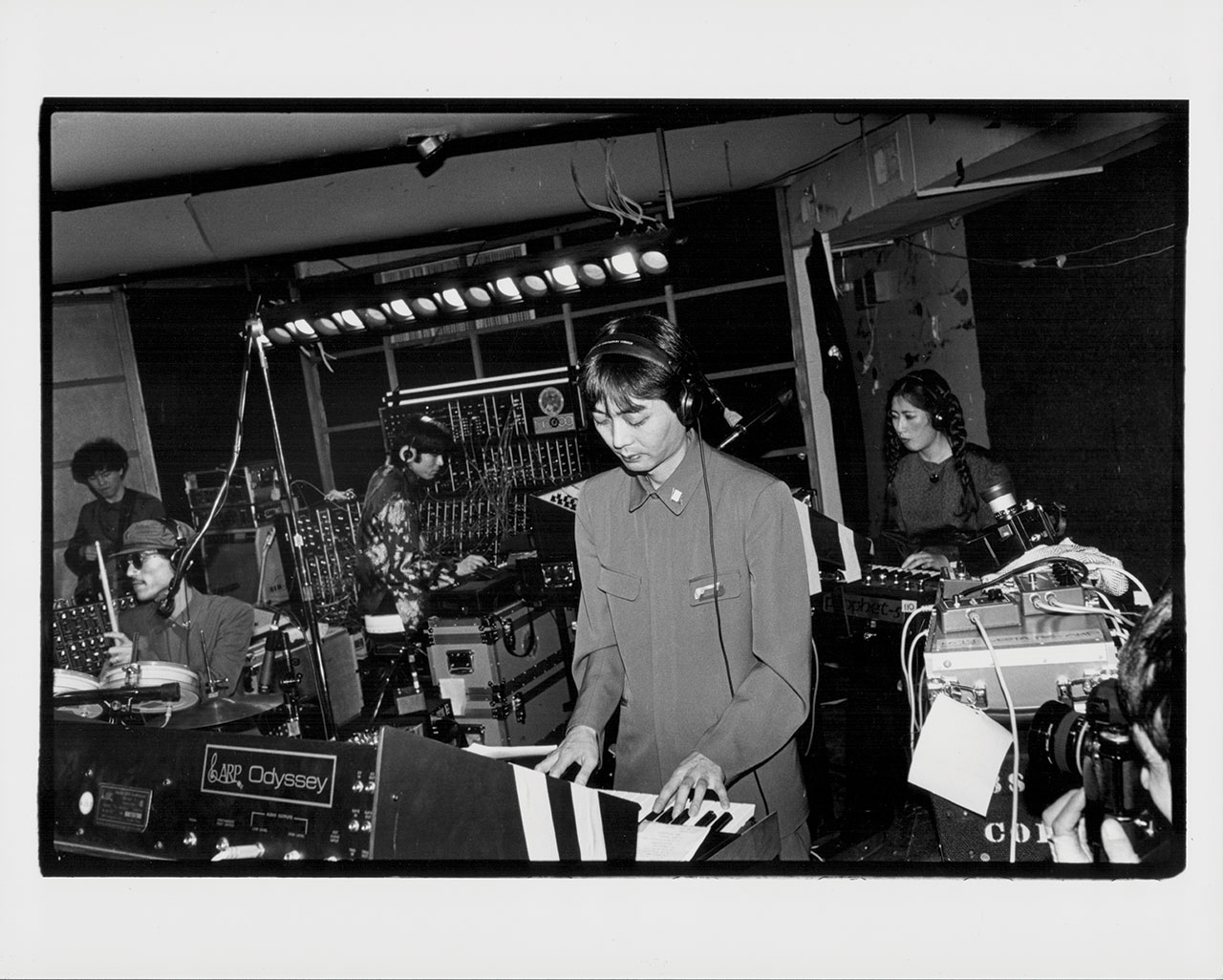

“That walk is maybe close to the image of the beginning or the ending of Solaris [1972], or some moments from Tarkovsky’s last film, The Sacrifice [1986]. It depends on my memory of the image that I’d built in my head. To me, music is very much like that. I always see some kind of visual image in my mind. Even when I was working with the Yellow Magic Orchestra in the 70s and 80s, I was seeing images in the studio – people listening to techno.”

One of the joys of listening to async lies in its tendency to reference Sakamoto’s own past. Life, Life, for instance, features the spoken tones of David Sylvian, a frequent collaborator, perhaps most famously on 1983’s Top 20 hit Forbidden Colours. “I had Sylvian’s files six years ago, when Japan was struck by a huge earthquake and tsunami,” Sakamoto says of the genesis of the new track. “Afterwards, in New York, we had a charity concert for that, with Laurie Anderson, John Zorn, Bill Laswell, Lou Reed and myself. I asked David to send me any musical files and he narrated a poem by Arseny Tarkovsky, who’s the father of Andrei.

“Since the very beginning, David and I have felt very close somehow, like brothers. I first got to know the band Japan when I interviewed them for a magazine back home. Soon after, I worked with them on Taking Islands In Africa [1980, co-written by Sakamoto and Sylvian], from Gentlemen Take Polaroids.”

There’s a sly chuckle in Sakamoto’s voice when he reveals that “when David and I work together, we have different egos and some friction is always there. When we don’t work, the relationship is perfect”.

Sakamoto’s connection to Forbidden Colours also feeds into a more serious aspect of the gestation of async. The song was originally recorded for the soundtrack of Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence, the Japanese POW drama in which he starred opposite David Bowie. A milestone in Sakamoto’s career, it marked both his debut acting role and his first film score. He and Bowie struck up a close friendship during the two months they spent on location in the South Pacific.

“He was a very down-to-earth man, not a superstar at all,” he recalls of Bowie. “He was wonderful. My strongest memory is of him talking about the cybernetic world and technology, people like [cyberpunk author] William Gibson and William Burroughs. Burroughs was a big influence on him, I believe. Sometimes we’d talk about politics, but mostly it was the arts and the future world.”

Like Bowie, Sakamoto was diagnosed with cancer in 2014. “I had cancer more or less around the same time that he had, so I know what it is and what it feels like,” he says. “When I listened to Blackstar [Bowie’s final album], his voice didn’t sound like someone who was going to die soon. It was very energetic and hopeful, with a lot of creative energy that I could hear. So it was a really big shock for me when he passed away.”

Sakamoto’s diagnosis partly explains the eight-year gap between async and his last solo effort, Out Of Noise: “I was the closest to death than I have been in my entire life, so of course that affected me so much. That’s one of the reasons it took so long to get the album done. The impact of the cancer was very big, so I dropped everything.”

It’s encouraging to discover that Sakamoto responded well to treatment and now feels in great shape. Not that the illness stopped him altogether. In 2015, he composed the score for Japanese drama Nagasaki: Memories Of My Son, along with the striking soundtrack for Alejandro Iñárritu’s gruelling epic The Revenant.

“That was one of the hardest soundtracks I’ve done,” he reveals, likening the experience to his Academy Award-winning work on Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 masterpiece The Last Emperor. “Working with Iñárritu was almost as tough as working with Bertolucci. It was so, so demanding. Both men are also composers, so they have very good musical ears. They sense things very musically.”

Sakamoto’s dazzling soundtrack CV also includes The Sheltering Sky, The Handmaid’s Tale, Wuthering Heights and Wild Palms, as well as more arthouse productions like Silk and 2002’s Derrida, which documented the life of the celebrated French philosopher.

Given that Sakamoto has described the process of scoring movies as being “like torture”, you can’t help but wonder what keeps drawing him back.

“It’s very stressful, but the excitement and joy you get by working with talented people like Iñárritu or Bertolucci isn’t something you can find somewhere else,” he says. “That’s why I have to keep doing it. By comparison, making solo albums is very lonely.”

The classical elements in Sakamoto’s music can be traced back to his formative years in Tokyo, listening to Debussy. Twinned with a fascination for electronica, Sakamoto’s first attempts at composition coincided with the advent of the synthesiser.

“In 1970 I wanted to use a computer for exploring music so I went to a university in Tokyo that offered that course,” he recalls. “But the way they used the computer for music was so primitive, I didn’t get much from it. A few years later I bought my first synthesiser and kept going. German rock was an influence at that time, especially Can, Kraftwerk and Neu!.”

Kraftwerk, in particular, played into the music of Yellow Magic Orchestra, the electro giants that he co-founded with Haruomi Hosono and Yukihiro Takahashi in 1977. Their futuristic fizz of synths, samplers and drum machines, allied to buoyantly memorable melodies, made them superstars in their native Japan and helped lay the framework for hip-hop, house and electro-funk.

By the time they disbanded in 1983, YMO had released eight albums and were the most popular group in their homeland. Although he says he’s proud of the trio’s legacy, Sakamoto admits he struggled with the impact that commercial success brought.

“Fame had never been my purpose or my aim,” he says. “It was totally accidental for me. I didn’t like it at all. I preferred being anonymous on the street, part of a crowd of a hundred thousand people at Shinjuku Station.”

Sakamoto’s solo career, which began with 1978’s Thousand Knives Of, afforded him the chance to experiment with different forms. 1983’s highly ambitious Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia travelled way off the map, serving as an appetiser for the global foraging of 1987’s Neo Geo.

Meanwhile, 1990’s Beauty was almost unclassifiable, navigating a path through techno, prog, Okinawan folk, Congolese dance and flamenco. Two years later, Sakamoto was conducting his own score at the opening ceremony of the Barcelona Olympics.

For async, Sakamoto says he started “with a big blank canvas and worked out that I wanted to hear the sound of normal things. Maybe the wooden panel of a speaker, a glass window, a coffee maker. I wanted to hear the real sound of tangible material, not the virtual world”.

This approach to his art, it seems, is the secret of Sakamoto’s longevity. “Maybe for other composers, when they make music, they’re imagining what people want to hear,” he suggests. “But I want to know what I want to hear. That’s at the very heart of my desire to make music.”

Your Shout

His work, both solo and with the likes of David Sylvian, has been pioneering. But is Ryuichi Sakamoto prog?

“He has created some truly amazing music over the years that would sit comfortably in any prog head’s collection, so I would say yes. I love his work.” - Buzz Elliott

“As prog as Jean-Michel Jarre and he’s prog.” - Andy Wyatt

“It’s more new age or adult contemporary instrumental music than prog rock. I’d say he’s 1% prog.” - J Lo Sanchez

“I have a few YMO albums on the iPod, love it. Also love his stuff with David Sylvian. A lot of that might go under synth pop, but the musicianship of the whole band is on another level. His piano stuff is more atmospheric, cimematic. I certianly wouldnt throw the magazine down in disgust if i stumbled upon a feature…” - Tobias Van De Peer

“He has had zero involvement with rock music. Owning too many k/boards and being mates with Bill Nelson are not sufficient qualifications.” - Prog Watcher

“Very progressive-minded artist, so if we include other electronic music pioneers as prog then he certainly fits the bill.” - Wedgepiece

“He certainly has made some beautiful, thought-provoking, intelligent music, solo and in collaboration with other talented musicians.” - Malcolm Clarke

“He’s surely a versatile artist with a broad view on music. Prog enough to me. I find his album 1996 just lovely.” - Bas Langereis

“Not! But a beautiful soundtrack and tentative artist. He could be linked to any genre. But prog, I don’t think so.” - Anthony Williams

“Very prog. Always innovative and beautifully grand music landscapes.” - Shep Kirkbridge

“Prog enough.” - Graham Lee

“Very. Music doesn’t often make me shed a tear, but Mr Sakamoto’s has. The man’s a genius.” - John Young

“Very prog!” - Jorge Bourdieu

“I place him in the electronic more than prog, but definite crossover in the same vein as Jarre, TD and Kraftwerk.” - Emma Roebuck

“Very! Don’t get me started… Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence is one of my fave film scores. I will leave it there.” - Rob Cottingham

“Very underrated in prog circles.” - Tom Gillitt

“Warm and full of emotion: prog in my book.” - Gary Morley

The Outer Limits: How prog are Epica?