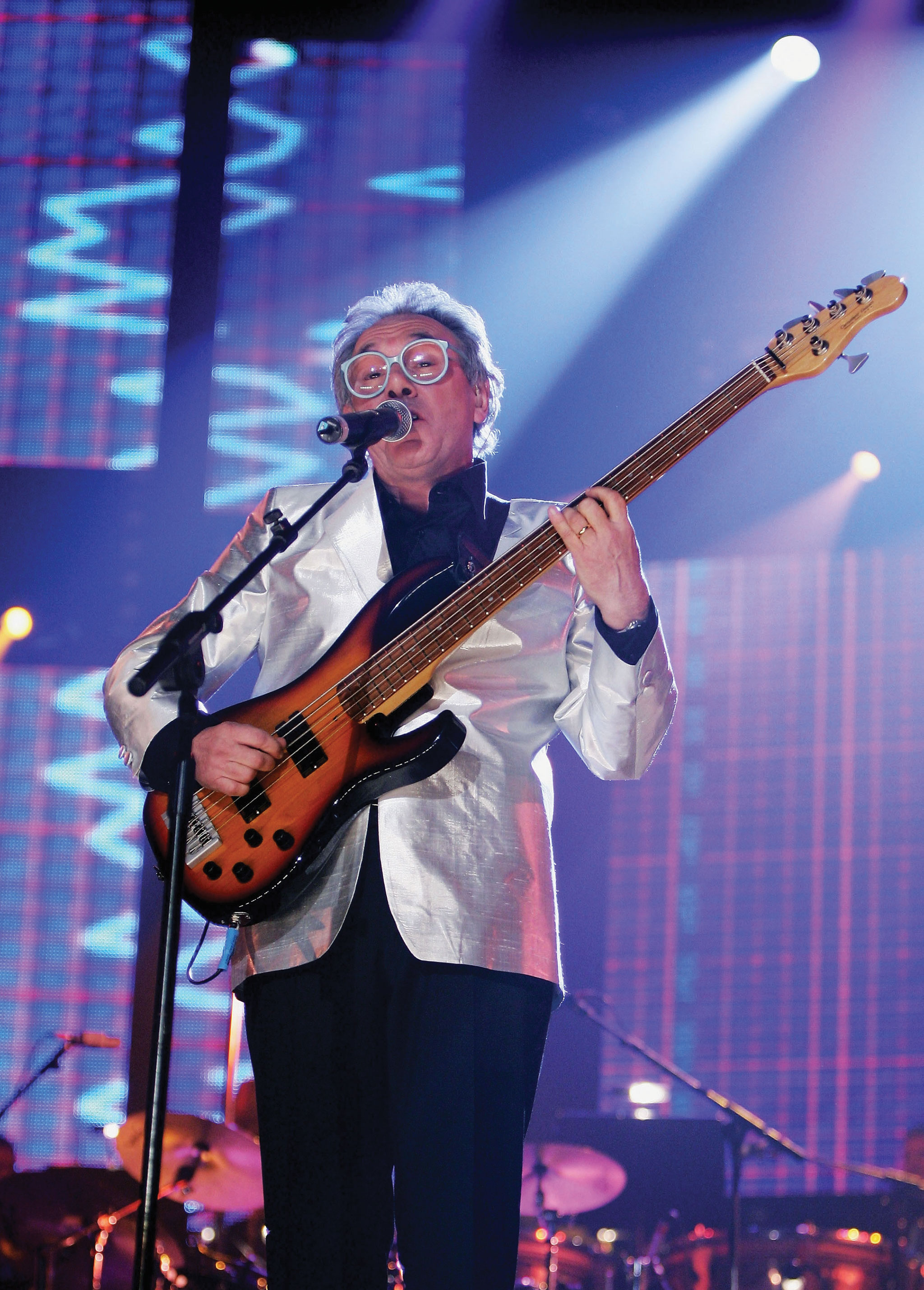

Buggles – award-winning producer and singer-bassist Trevor Horn, alongside keyboardist Geoff Downes – were the result of a science experiment designed to fuse prog at its most complex and cerebral with pop at its most artful and intelligent. No wonder Downes and Horn went on to join Yes for their 1980 album Drama and the subsequent tour, while Horn would produce 1983’s 90125 and 1987’s Big Generator.It’s hardly surprising, either, that 10cc’s 1974 album Sheet Music is one of Horn’s favourites, and that 10cc guitarist and songwriter Lol Creme remains a close associate.

Buggles might be best known for the naggingly infectious near-novelty hit Video Killed The Radio Star, a No.1 around the world in September 1979, but they also released two very clever and near-conceptual long-players – 1980’s The Age Of Plastic and 1981’s Adventures In Modern Recording – that prove there was a lot more to them than chart pabulum.

Their music had a tricksiness and far-sighted sense of visionary wonder typical of true prog fans. It also evinced a high-gloss sheen and the sort of mad studio skills you’d expect of someone whose productions for ABC, Dollar, Malcolm McLaren and the ZTT label – home of Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Art Of Noise and Propaganda – led to him being dubbed ‘the man who invented the 80s’.

Horn and Downes receive the Outer Limits gong at this year’s Progressive Music Awards, and today Horn laughs, “I suppose I have skirted around prog,” when asked whether he and his Buggles partner have spent 40 years voyaging on the margins of progressive rock.

Both certainly have full prog CVs: Downes has been a member not just of Yes but of Asia too. And Horn first saw the prog band he would end up joining back in 1975, at De Montfort Hall in Leicester, on the Yesterdays tour, during what he terms “the golden era of prog”.

“I was a big Yes fan, and of course I ended up joining Yes,” he says. “But I liked lots of other prog, like Caravan and Genesis, although never as much as Yes because the rhythm section was never as interesting. I’d never heard anything like them before and I’ve not heard anything like them since.”

For Downes, Buggles were equal parts prog and pop. “What amazes me is the amount of detail we put into those recordings,” he says. “We’d stay up all night, experimenting in the studio. It was progressive pop, I guess.”

He considers Buggles’ antecedents in the progressive pop stakes to have been 10cc and ELO. “Though they were known as pop bands, they had lots of progressive ideas,” he argues. “Those early 10cc records such as [1973 debut] 10cc and Sheet Music were pretty out there, and Godley & Creme took that even further. Even Abba had sections in their music that were quite intricate. We loved all that studio trickery and experimentation. Parallel to that were bands like Yes, who were experimenting in the studio in a more progressive rock format.”

So did Buggles provide the bridge between 70s prog and 80s pop? “I think so,” Downes says, adding that, for some, Buggles were a pop step too far. “Obviously when we first joined Yes there was a huge outcry from the diehard Yes fans: the idea of a couple of interlopers from the pop world suddenly stepping into this revered band. But in hindsight, both myself and Trevor were musicians, not pop guys. We were very much into Yes and progressive music. It’s just that our opportunity came to make pop music and we took it.”

Leeds College Of Music graduate Downes was a former member of obscure rockers She’s French, and a session musician and composer of advertising jingles when he met the Durham-born Horn via an advert at the back of Melody Maker.

“He was putting together a live band for Tina Charles [pop-disco diva whose single I Love To Love was No.1 in 1976] and he gave me the gig as the keyboard player,” remembers Downes, whose equipment clinched the deal.

“I’d borrowed a Minimoog from a friend, which not many people had because it was a bit of a luxury item, and Trevor later told me that’s why he gave me the job,” he laughs. “We’re both very technologically minded, even now.”

Horn might have had one foot in mainstream entertainment – he played bass in the orchestra for BBC TV show Come Dancing – but he had another in the avant-garde: his ambition, he asserts, was “to combine Kraftwerk with Vince Hill”. He recorded two singles as Big A, including Caribbean Air Control, which failed to chart but received considerable daytime radio play, and a 1978 album as Chromium, with help from Downes and composer Hans Zimmer. The result, Star To Star, was proto-techno dance music.

“The idea was sci-fi disco,” says Horn of Chromium’s music, which dovetailed nicely with other contemporary examples of the electronic form, such as Space’s Magic Fly.

After a series of collaborations – “mainly rescuing peoples’ dodgy demos”, as Downes puts it – he and Horn joined forces with musician Bruce Woolley, who helped co-author Video Killed The Radio Star. But before long, Woolley secured a solo deal with CBS, and then there were two.

“There weren’t that many pop duos about back then,” says Downes of the pre-Pet Shop Boys/Soft Cell/OMD era.

But then Buggles were never really meant to be an actual living, breathing entity at all. “We were more a concept – a virtual band,” he ventures. “It was just us messing round in the studio.”

“We had this idea where a guy, working in the basement of a record company, would make up groups and records on a computer,” adds Horn. “One of the groups this guy invented was called Buggles, and they had a song called Video Killed The Radio Star.”

Buggles might have been fictional, but their success was very real: Video… was the first chart-topper for Island Records and it went to No.1 in 16 countries. It was an early synthpop hit, alongside M’s Pop Muzik, The Flying Lizards’ Money and Gary Numan’s Are ‘Friends’ Electric?.

Buggles’ debut album, The Age Of Plastic, explored modern-age anxiety with songs about gangsters, virtual sex machines and media saturation_._

“I was trying to write about different things,” muses Horn, who cites author JG Ballard as an influence on his writing at the time. “The whole idea of ‘the plastic age’ came to me after one of the guys at Island said I looked a bit plastic in one of the pictures. I thought, ‘Yeah! The Plastic Age!’”

Video… made Buggles pop stars, but they chose another path – as prog heroes. They were invited to join Yes, partly because they shared management and partly because of Horn’s high, Jon Anderson-ish voice. Anderson (and Rick Wakeman) departed Yes in early 1980 following aborted sessions for their new album and the band needed a replacement. Yes also saw Buggles as a way out of their post-Tormato impasse. In addition, it probably didn’t do any harm that Buggles’ pop fame gave Yes bassist Chris Squire extra brownie points with his kids.

“When we went down to meet the band,” marvels Horn, “his kids were waiting at the door with their autograph books because we were pop stars!”

After a successful audition of a new song entitled Fly From Here that Horn and Downes believed might work for Yes, they were invited to a rehearsal.

“It was amazing,” says Horn. “I’d never been close up to a rock band like that before, people who played like that. It was the most exciting thing I’d ever heard.”

Was he nervous? “I was shitting myself!” he says.

Did he meet resistance from fans? “Some of the fans were pissed off, yeah,” he admits. “I would have been pissed off! I was no Jon Anderson. He was a career singer. I was just clinging on by my fingernails.”

Nevertheless, Buggles gave Yes that certain modern-sounding something they’d been missing. “Chris had always wanted Yes to keep going through changes and new directions and reinventing themselves,” says Downes. “I think they saw something in us to propel them into the 80s. And I think that did happen – our influence on the Drama album paved the way for 80s Yes. We set them on another course.”

Horn agrees with Downes’ assessment of Yes’ 10th studio album. “I think we did push the boat out,” he says. “The guys in Yes played out of their skins. The drumming on that album in incredible, Steve Howe’s guitar parts are incredible, Chris sounds incredible – we really did a solid album.

“I’m really proud of Machine Messiah: it has so many elements and the scene changes that Yes are known for, but it also has this modern sound, and that was maybe something Yes had been missing on the previous album Tormato. People were surprised that it came up to a lot of high expectation. Drama has grown on a lot of diehards over the years and been accepted as a worthwhile part of Yes’ catalogue.”

There followed the Drama tour, which Horn and Downes had mixed feelings about. “It was amazing,” says Downes, “playing these big arenas, but me and Trevor were really just a couple of back-room boys tinkering round in the studio, and suddenly there we were in front of 20,000 people. It was pretty hairy, I can tell you.”

Soon, however, their tenure with the prog overlords was at an end. “Yes collapsed at the end of that UK tour, at the end of 1980,” recounts Downes. “Chris and Alan [White] went their own way, Steve wasn’t doing a lot, so Trevor and I decided to go back in the studio for another Buggles album.”

This time, they were armed with a brand new Fairlight computer – all the better to sample with – and a renewed sense of experimental purpose. “After our spell with Yes, our writing changed a little bit,” Downes says. “It wasn’t so pop-oriented and there were more moody sections.”

Buggles’ second album, Adventures In Modern Recording, functions as a companion piece to Drama. Indeed, one of the tracks, I Am A Camera, is an alternate version of Into The Lens from Drama, while the 2010 reissue of Adventures… features the early demo of Fly From Here, part of a suite that Horn and Downes would later complete for Yes’ 2011 album of the same name.

While the album was Buggles’ swansong – Downes left during recording to join Asia while Horn went on to, well, invent the 80s – if anything, Adventures… sounds better today; more radical than ever. It’s ironic given their twin reputations – pop lightweights and prog behemoths – that Yes’ Drama and Buggles’ Adventures… flow together so seamlessly.

“Yeah,” notes Horn, ever the dry northerner, “but you know, we always had aspirations…”

The credits to Adventures… read like a who’s who of 80s sonic architects, including as they do future members of Art Of Noise and many of the sessioneers and studio bods who would help Horn give the new decade a bold, multilayered and lavishly textured new sound via the output of ZTT and the records of ABC, Dollar, Frankie, Propaganda and Grace Jones. You might even recognise the name of Chris Squire on those credits, just as Steve Howe’s name would later appear on the credits to Frankie’s Welcome To The Pleasuredome and Dave Gilmour’s would appear on Jones’ Slave To The Rhythm. Get close to the edge of either pop or prog and you’ll find the other staring you in the face.

“I always thought they were two sides of the same coin,” reckons Horn, who cites Yes’ Owner Of A Lonely Heart as his shiniest, most towering prog-pop edifice to date. “Pop is one of the few art forms that is progressive. And the whole idea of progressive rock was to not be formulaic and try to stretch the format. On the surface, what Buggles did was pop. But look a bit deeper and there’s some quite progressive stuff going on.”

YOUR SHOUT

Video might have killed the radio star, but just how prog were Buggles?

“Considering the prog influences they brought into the group, and the structures of some of the songs with different movements, I would say they were pop prog at least. More so on their second LP than the debut. Stuff from their first album, like the title track, were prog to me, but the delightful Elstree is more of a pop song.”

Eric Lowenhar

“They were prog when they recorded as Yes.”

Terje Embla

“Not in the slightest? Geoff playing with Yes doesn’t change what The Buggles actually was.”

Derrick Babb

“About as prog as Simple Minds/Tears for Fears etc who have also had good coverage in your mag. They’re the type of act who when they’re reappraised by prog fans, they unveil a level of talent on album tracks that was missed the first time around due to being perceived as chart acts. The Age of Plastic is fantastic by the way, and Drama is still my favourite Yes album.”

Jason Richards

“Not very – probably more so on their second LP. Definitely up there with Yellow Magic Orchestra as one of the most ‘fun’ synth-pop bands though”

Simon Slator

“Are we talking about the duo that added a few members and became the Yes of my generation?”

Max Brighel

“Proto-pop-prog really – the electro drums/synthesised side of their work less prog than some of the lyrics/concepts IMHO.”

Titus Jennings

“Up there with Elbow. Make of that what you will!”

Morto

“The Buggles? YES! But in a poppy way.”

Bas Langeris

“They were in my humble opinion. On their first record they were leaders in sound design and using technology or making things sound as if it was made electronically but really wasnt. On the second album they were experimenting with the fairlight and other devices even though all in all the second one is weaker than the first one. To me they were progressive in a more literal sense. They made music with a progressive approach rather than the prog rock sound of Yes and co. To me they were more progressive in the way Kraftwerk was progressive.”

David Merz

“You wouldn’t be asking if they hadn’t joined Yes. Not very prog.”

Mike Sargent

“They drew inspiration from JG Ballard etc – proggy enough for me!”

Andy Funnell

“Meh… Not that much, despite the heritage of Horn and Downes.”

Steven McCarthy-Hunt

“They were pretty progressive compared to most synth pop!”

Luis Echeverria