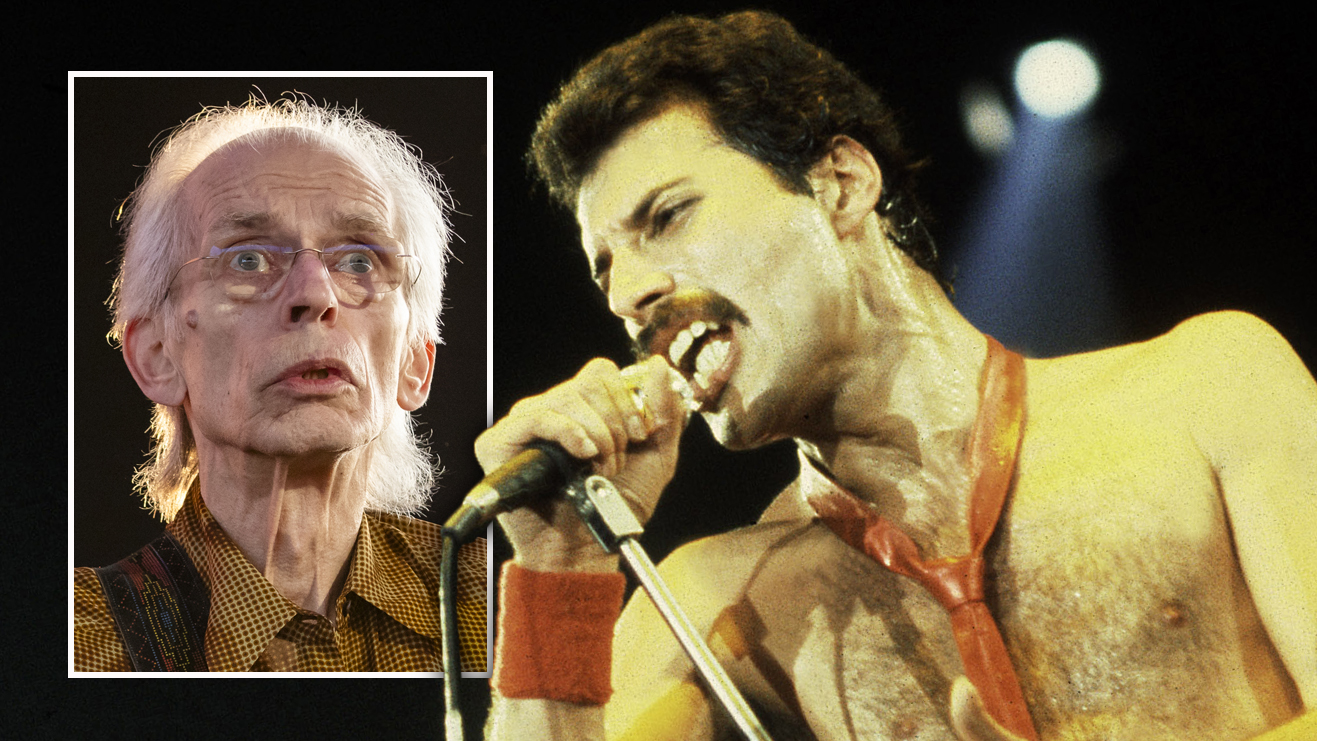

“I lie to them and change the goalposts… you build up techniques of throwing the curveball of discomfort. If it gets comfortable I change it”: David Thomas calls Pere Ubu “avant-garage” – but how prog are they?

They’re unmistakably American, but their lead visionary names Henry Cow, Soft Machine, Gentle Giant and Van der Graaf Generator among his motivators, and explains why his band is definitely not punk

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

They may have jokingly dubbed their music “avant-garage” and been lumped in with the punks, but they’ve proved an entity unto themselves. With their frontman David Thomas claiming they “refocused” prog rock in the 70s, in 2014 we asked: how prog are Pere Ubu?

Pere Ubu fixes things – that’s what we do,” says Pere Ubu vocalist David Thomas on a video broadcast uploaded to their Ubu Projex website. “The English prog rock scene was truncated by the corporate arrivistes of punk rock.

“I was determined that we were going to fix that. In the real world, the real Sex Pistols was a band called Henry Cow. It’s said that Pere Ubu refocused rock music in the 70s, but in the real world what we did was refocus prog rock. Carnival Of Souls then is the album that we do 40 years later. Understand?”

Well, not entirely, we must admit, but we’re certainly intrigued…

Formed in 1975 in Cleveland, Ohio, Pere Ubu hit the UK scene with a triple whammy in 1978, their powerful and dark vision already fully formed on Datapanik In The Year Zero, a collection of early singles; their debut album The Modern Dance, available on import on Blank Records; and a second album, Dub Housing, released on Chrysalis. “We knew it at the time that The Modern Dance was such a new thing coming out of nowhere,” Thomas says.

Their style, which he later dubbed “avant-garage,” married the rock’n’roll clout of the MC5 with unpredictable currents of electronics and saxophone, all buckled into unusual shapes and structures. They carried a peculiar vein of dark humour and absurdity into something ominous, jarring and extraordinarily powerful. “We aren’t experimental – we know what works and what doesn’t,” says Thomas now, but they were back then.

They have produced 14 albums, which have veered stylistically from the dual percussive complexities of The Tenement Year (1988), on which former Henry Cow drummer Chris Cutler teamed up with Scott Krause; the poppier Cloudland (1989); the eclectic, adventurous Ray Gun Suitcase (1995); and now Carnival Of Souls.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“What marks this band apart from everything else is the bravery of what they do,” says Ubu fan Matt Stevens of The Fierce And The Dead. “You can define prog in the nostalgic way, of being steeped in the 70s. Or you can see it as a chance to push boundaries and try something new. If Yes are icons of the former, then Pere Ubu are heroes for the latter.”

Interviewing Thomas is as disconcerting as listening to the group’s music. He’s articulate and keen to explain his idiosyncratic takes on the world, which are spiked with humour. He seems almost diffident, but he can suddenly turn prickly. “All journalists are scum,” he announces. “No offence. I used to be one myself.”

None taken. So could you expand on your views on prog and punk?

Pere Ubu songs don’t make a speck of sense, but there is this organic wholeness to it

“The first things that come to mind about English musical traditions are the sort of solo English folk voice of the early 20th century, like Walter Pardon. And then Norma Waterson, Martin Carthy and Eliza Carthy, all of that. The second thing is English prog rock: Soft Machine and Gentle Giant, Henry Cow, Van der Graaf Generator, Incredible String Band, Genesis.

“I don’t think there is anything more English than Soft Machine,” he continues. “It screams ‘This is England!’ and I was always attracted by that. I remember going to see a lot of those bands when they came by Cleveland in the early 70s, so I think that was a great tradition that basically was killed off.

“Each national or racial group has their own strengths and weaknesses, and one of the weaknesses of the British is that they deprecate their own culture. Henry Cow was doing totally revolutionary stuff with vastly talented musicians and it had what I would call an English naïve socialism to it. Not that you believe in it, but damn it, these people believe – they’re strong!”

Thomas says that when punk broke, he was already one of the naysayers, prophesying that people would regret it in years to come. One might have thought his group’s visceral music and its influences might have made it a fairly close relative – but evidently not.

“I admire John Lydon; he’s done wonderful work,” Thomas says. “But with the Sex Pistols it was more of the English imperialist notion, where the music wasn’t their music, it was the fashion and the appearance and the surface things that were English. There’s no difference between the Sex Pistols and Simon Cowell; and the whole notion of pop idolism is simply punk taken to its logical conclusion, where anybody can do it – we’re all talented. Well, fuckin’ hell, no!”

Thomas doesn’t want to be nostalgic about prog, but although artists like Peter Hammill, whom he admires, are still doing good work, he feels its heyday is gone. “It’s a voice from an extremely strong geographical, temporal, cultural world that no longer exists, but it does speak to you and it has that Atlantean quality to it.”

So was Thomas serious about “fixing prog rock?” “I’d suggest that in some way we do carry on the spirit of it,” he nods. “Not in any stylistic way. I mean, Pere Ubu is based over here and is really more an English band at this point than American, but it’s still driven by this Mid-western rock groove.

“If you sit down and really analyse Pere Ubu songs, they don’t make a speck of sense, but there is this organic wholeness to it – some of the beats have been flipped around, dropped and picked up again later and you have to remember all that, but it all sounds natural. I think that’s a prog rock idea. But I wouldn’t want to go out and ‘pastiche’. It would be as false as some white band from Birmingham playing reggae,” he laughs..

The perennial Pere Ubu trademark – apart from Thomas’ vocals – is their mix of rock music and untempered synth playing. It started off in 1975 when Thomas and a group of “urban pioneers,” as he calls them, moved from the suburbs into the run‑down inner city of Cleveland and into a large house called The Plaza. It was owned by Allen Ravenstine, who also owned a modified keyboard-less EML synthesizer, and joined the group basically because “he made cool sounds and he was a cool guy”.

While Hawkwind used synths to evoke a picture of outer space, Ravenstine’s playing conjured up the sound of roadworks, slamming doors, TV interference, passing cars and howling wind. “We were aware of the potential of sound, of the things the Velvets were doing, Can and Neu! and the synthesizer groups of the day like Silver Apples and Beaver & Krause. Some of the local rock bands thought we were morons,” Thomas says.

Now the group have two players of electronics: Robert Wheeler on EML synth and theremin, and Gagarin on digital electronics. Thomas is enthusiastic about this clash of analogue and digital and also the introduction of a new timbre into the group, jazz clarinettist Darryl Boon.

Carnival Of Souls was originally a live ‘underscore’ for a showing of the 1962 horror film of the same name at the East London Film Festival 2013, although Thomas insists it’s not actually about the film. Musically, it’s a mix of compact, aggressive songs like Golden Surf II and more loosely structured, semi-improvised songs and strange transmissions like Visions Of The Moon, with Thomas singing, ‘I live in a box on the moon’. There’s a noir feel about the album, with numerous lunar images, in which the star exerts something of a malign influence.

I think that question, ‘What does it mean?’ is critical… It does mean something; there is a very specific point of view

Thomas mentions that he uses tricks to keep the musicians fresh. “I lie to them and change the goalposts at the last minute,” he shrugs. “[Bass guitarist] Michele [Temple] is brilliant at working things out, but if she’s worked it out too much, I’ll say, ‘That’s not this song, that’s the other song‘, and, ‘For this I just want you to play two notes’. And she’ll do it and it will be perfect. So you build up techniques of throwing the curveball of discomfort. It’s always uncomfortable in Pere Ubu. If it gets comfortable I change it.”

The group’s name derives from a monstrous character dreamt up by French author and playwright Alfred Jarry, who first appeared in the play Ubu Roi in 1896. Thomas is a fan of Jarry’s work as the founder of ‘Pataphysics, the science of imaginary solutions, where exceptions are favoured over the norm and where absurdity is relished.’

On the Ubu Projex website, Thomas writes that Carnival Of Souls is about a man who discards his clothes, slips into a river and watches the moon through the water. He also says it concerns monkeys and strippers, and then imagines Peter Hammill in a George Clinton role fronting a white Funkadelic. We both laugh at the idea.

“Exactly!” Thomas continues. “But I can conceive of Peter Hammill being him, and if, in this alternate universe, that was this, then Pere Ubu is this, and then this new album is this.”

When I offer, then, that Thomas must be throwing in a few red herrings in a pranksterish kind of way to people who want easy answers to Carnival Of Souls, his response suddenly becomes rather heated. “When the album is done, I think about how I am going to explain what this means. Well, the way that you would describe a non‑logical, anti‑logical work is to use something that is in itself metaphorical or allegorical or non-logical.

“I think that question, ‘What does it mean?’ is critical. It’s not my job, but it’s supposed to be your damn job. It does mean something; there is a very specific point of view. Turn on the damn TV and they are all monkeys and strippers. What is X Factor but a bunch of monkeys?”

You can trace a line from the very beginnings to Brian Wilson to Lou Reed… we’re still on that line

Given his assessments of popular culture, it’s surprising to hear Thomas claim that Pere Ubu are actually a mainstream act. “You can trace a straight line from the very beginnings, let’s say Heartbreak Hotel, to Brian Wilson to Lou Reed. Into the 70s there was a greater maturity of narrative, of the language of music and the development of technique. Everything was evolving and moving forward. Pere Ubu joined that straight line.

“This was not a good direction for companies to go in. This is why they were so delighted when punk came along – because then they got to regurgitate this safe crap. We are the mainstream, because we’re still on the line. The rest have gone like this,” he says sweeping his hand to one side. “And that’s not our fault.”

Mike Barnes is the author of Captain Beefheart - The Biography (Omnibus Press, 2011) and A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s (2020). He was a regular contributor to Select magazine and his work regularly appears in Prog, Mojo and Wire. He also plays the drums.