They’re progressive without descending into manic free-form eight-minute solos or mental time signatures,” says Tom Anderson of prog-folk combo Common Tongues. He’s eulogising the music and methods of Australian cult band The Church, who have just released their 21st studio album since forming in Sydney in 1980.

“What they do is on the more accessible side of prog, where the song shines through,” attests Anderson. “You can hear how the song might have begun on acoustic guitar, before the sonic embellishments and experimentation. They’re like Pink Floyd in that respect. Their songs take you on a journey, and they keep you on your toes sonically. A lot of the songs seem to come out of extended jams, which is quite a prog way of working. They operate with the creative freedom that prog allows, at the limit of their own imagination.”

The Church are nothing if not broad (geddit?). They can do succinct three-minute melodic rock, but they also know how to stretch out – look no further than grandiose mini-adventures such as Grind from 1990’s Gold Afternoon Fix, or half-hour expressways to your skull such as The Sexual Act from 2004’s Jammed, which neatly bookend mainman Steve Kilbey’s heroin phase. In their 35-year existence, they have made music that could variously be termed post-punk, indie, goth, shoegaze, psychedelic and, of course, prog.

They started out as 60s-worshipping peers of Echo & The Bunnymen and REM, and at certain points threatened to become majestic stadium rockers as massive as Simple Minds and U2. But they ended up ploughing their own furrow, with a small but devoted following that hangs on their every release, up to and including new album Further/Deeper, which is as fine as anything The Church have ever done.

What they do is on the more accessible side of prog, where the song shines through.

When it comes to tags, given that The Birthday Party, The Go-Betweens, The Triffids and The Saints are no longer active, Prog suggests that an appropriate one might be Australia’s ‘Greatest Living Cult Band’.

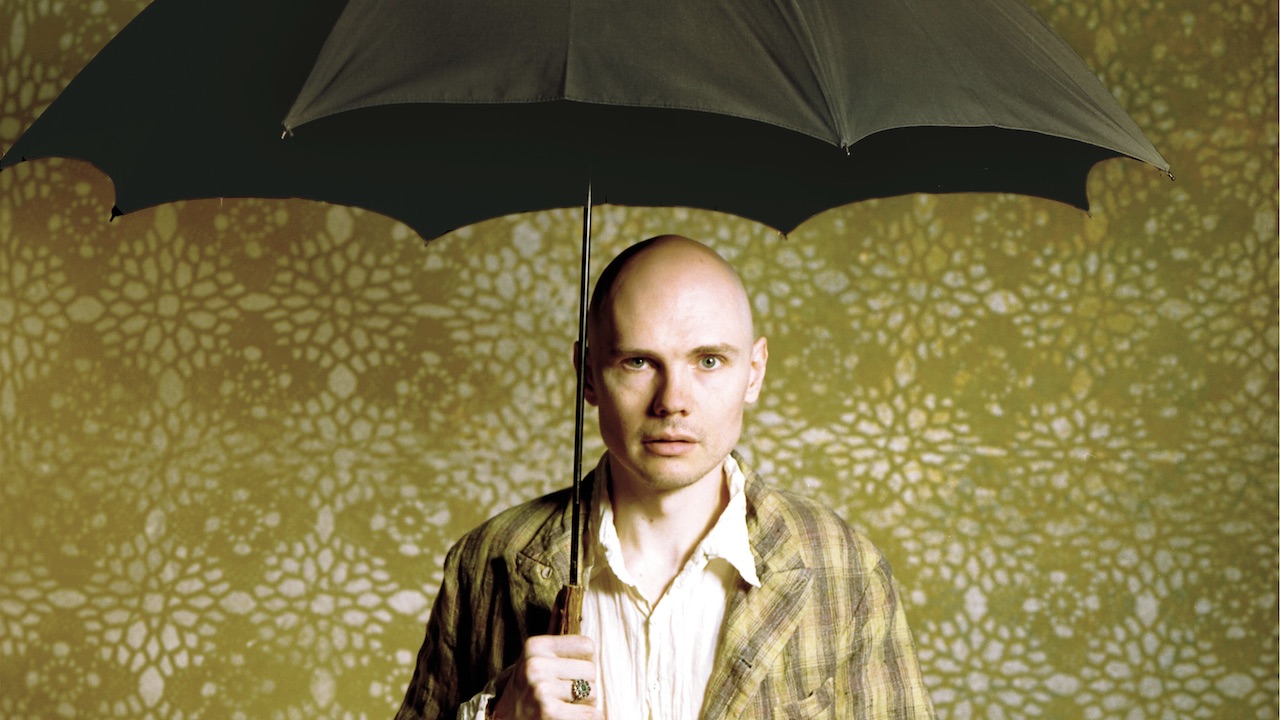

“Ha ha!” laughs Kilbey from Sydney via Skype, somewhat taken aback, skinning up to celebrate the accolade and repeating the phrase with some relish. “Australia’s greatest living cult band? Wow.” He pauses, then considers his response. “You can put that on my tombstone.”

Kilbey, who describes himself as a “very immature” 60, isn’t ready for memorials yet. He’s got too much dope to smoke and too many records to make. And too much prog to listen to.

“There’s a lot of prog in what we do,” he concedes. “I’ve always liked prog. I unashamedly love Genesis – especially with Peter Gabriel, they were fucking amazing – and some of Yes, up to Tales From Topographic Oceans. I like Krautrock, Be Bop Deluxe, Sigur Rós… You Took [from 1982 album The Blurred Crusade] was definitely an early stab at prog. And things like Operetta [from 2009’s Untitled #23] or Globe Spinning from the new record are pretty prog. I really like King Crimson – the first albums and even when they were doing Starless And Bible Black. I have a lot of respect for Fripp. Eno, too. All our records have had prog ambition or pretensions.”

Prog read that The Church started playing snippets of Yes’s Roundabout and And You And I at a gig. True? “I don’t think we’re clever enough to play either of those,” he chuckles. “We’re more likely to quote Wild Thing than Roundabout it’s my favourite Yes song, but it’s too hard to fuckin’ play.

“The one thing about prog that I never liked was the outrageous time changes,” he continues, adding that former Church guitarist Marty Willson-Piper was “the one with all the Barclay James Harvest B-sides”.

“It’s like on Heart Of The Sunrise, you’ve got this really great bit where Jon Anderson goes [starts singing], ‘Sharp… distance… How can the wind…’ And you go, ‘Wow, what a beautiful song.’ Then suddenly it goes [mimes dense barrage of technically complex instrumentation]… You know, all this complicated stuff. I like music that flows naturally.”

When The Church emerged in the early 80s, they were aligned briefly with the ‘Paisley Underground’ acts from the States – Rickenbacker-wielding 60s heads “disgusted” (Kilbey’s word) by the synth fops of the new romantic scene. He notes that fellow Byrds maniacs The Smiths were alleged to have formed after seeing The Church play in 1982 at The Leadmill in Sheffield.

For their first few albums – 1981’s debut Of Skins And Hearts, 1982’s The Blurred Crusade, 1983’s Seance and 1985’s Heyday – The Church enjoyed “our bright and shiny period”. Then in 1988, Starfish, aided by the hit Under The Milky Way, propelled them on to the next level of fame, with its attendant diversions.

“Drugs and sex and money were kind of in abundance if you wanted them,” Kilbey recalls. “It wasn’t like Bon Jovi or anything, but if you wanted those things, they were on offer. It was pretty mild stuff that I did. It’s like in Keith Richards’ book where he says he’d go to bed with women but was fucking lonely so he just wanted to kiss and cuddle – I was the same as that. I wasn’t a pussy-hound whipped on by my libido.”

The success of Starfish caused pressure in the ranks and things turned sour. Follow-up Gold Afternoon Fix was, judges Kilbey, “a mediocre record”, and although 1992’s Priest=Aura remains a highlight of their catalogue, it was too late. “I still think that’s an amazing record, but the philistines in 1992 couldn’t dig it,” he gripes, although he remembers a rave review: “‘The sound on this record will have all the shoegazers running to mummy to beg them to ask for new effects pedals.’”

Asked whether The Church could have been stadium rock contenders but instead got derailed by circumstance, he replies: “Nah. We derailed ourselves by making Gold Afternoon Fix. We were treading water when we should have landed the killer punch. But we were never destined for the arenas. We weren’t vivid enough.”

There was also the small matter of Kilbey’s introduction to the joys of smack, courtesy of his best mate, Grant McLennan of The Go-Betweens. He recalls: “I was very anti it, and then suddenly I had this best mate in the whole world, and we were sitting in a pub one night and he said, ‘Fuck it, I’m going to get some heroin.’ Talk about peer pressure – as Mr Rock’n’Roll I had to pull out a 100-dollar bill and say, ‘Get me some too.’”

Kilbey will never forget that first hit.

“As soon as that first snort hit my nostrils, I was gone,” he admits. “I was like, ‘Wow, this is how I’ve always wanted to feel.’ And the feeling was that I liked myself. It made me feel comfortable with myself. Suddenly Grant and I were in this stupid heroin brotherhood. I had a lot more money than him, but he had the contacts. We were showing off to each other, egging each other on with bravado. Within a very short space of time, we were surrounded by heroin. I had this house in Surrey Hills and everybody renting the rooms was using heroin.”

At this stage, Kilbey wasn’t injecting. That pleasure came later, when a medic friend showed him what he was missing. “She saw me smoking a big line and she said, ‘What a waste.’ So my first shot wasn’t in some back alley, it was from a very intelligent, very friendly doctor. It was something I looked upon with abhorrence, but now there were people shooting up.”

Was his house like Jesse Pinkman’s in Breaking Bad – epic squalor?

“No, it was rundown and iffy, but it never reached epic squalor,” he says. “But it wasn’t a pleasant place to be. That was a really awful period for me, although I was still making music. I was a functioning junkie, mostly.”

Nevertheless, he reveals, he couldn’t properly make music unless he’d taken heroin. He was, he adds, “sick… trapped…” He tried cold turkey and different rehab treatments, but nothing worked. Until the turn of the century when, after a decade of addiction, he “miraculously managed to slip off the hook”. He felt as though “a curse had been lifted”. “It’s insane that I was so obsessed with it – totally obsessed for 10 years.”

Did he still have any of the money – the millions – accrued by Starfish? “No, none,” he says. “My studio with loads of great gear, all my guitars, my piano, my house, my car – I put everything up my arm. Even relationships and friends.”

How about his kids? (He has several children by different partners.) “One of them hasn’t really forgiven me and probably won’t, and the other one is working on forgiving me,” he says. “It’s certainly no fun having a junkie father – I was flakey, unreliable, either panicking or nodding off, with undesirables around the house, just being hopeless.”

He doesn’t agree when Prog ventures that some of his 90s releases such as Magician Among The Spirits (1996) and Hologram Of Baal (1998) were “heroin follies” (it was meant as a compliment), but he does concede that he was “lax and lazy” on smack. He compares this phase to Big Star circa Sister Lovers, when it was anything goes. “There’s a sort of nasty haze over those records, which I can’t work out if it’s just in front of my eyes or tangible to people listening out of curiosity,” he ponders. “They conjure very dark feelings.”

Is he lucky to be alive?

“Well, I never OD’d, but I did get involved in some sticky situations,” he offers. “There were criminals looking for me, and knives, and being assaulted and running away from coppers and being locked up. I don’t recommend it to anybody. I was never the glamorous wasted character, I was the bloated embarrassment. If I was on heroin now, I’d be saying to you, ‘Hey, mate, do you want to put 100 dollars in my PayPal?’ I was outrageously rude and stupid.”

By contrast, the Steve Kilbey of 2015 is a funny, candid, affable interviewee. Since he quit, he’s discovered a new him. “I found myself to be – surprise, surprise! – a reasonable old guy,” he laughs, citing The Flaming Lips when he describes his persona at the height of the junkie madness as “ego tripping at the gates of hell”.

Since 2003’s Forget Yourself, he has been back on track, making terrific music, some of which, notably Untitled #23, has been highly acclaimed – one newspaper, Kilbey tells Prog proudly, gushed that it was one of the best albums ever made, up there with Abbey Road and The Dark Side Of The Moon. “I don’t believe that myself, by the way,” he adds, just in case.

He’s delighted that people are rediscovering The Church, and struggles to fathom why their latest album, Further/Deeper, sounds like the work of a much younger band. It has the shimmering energy of a debut.

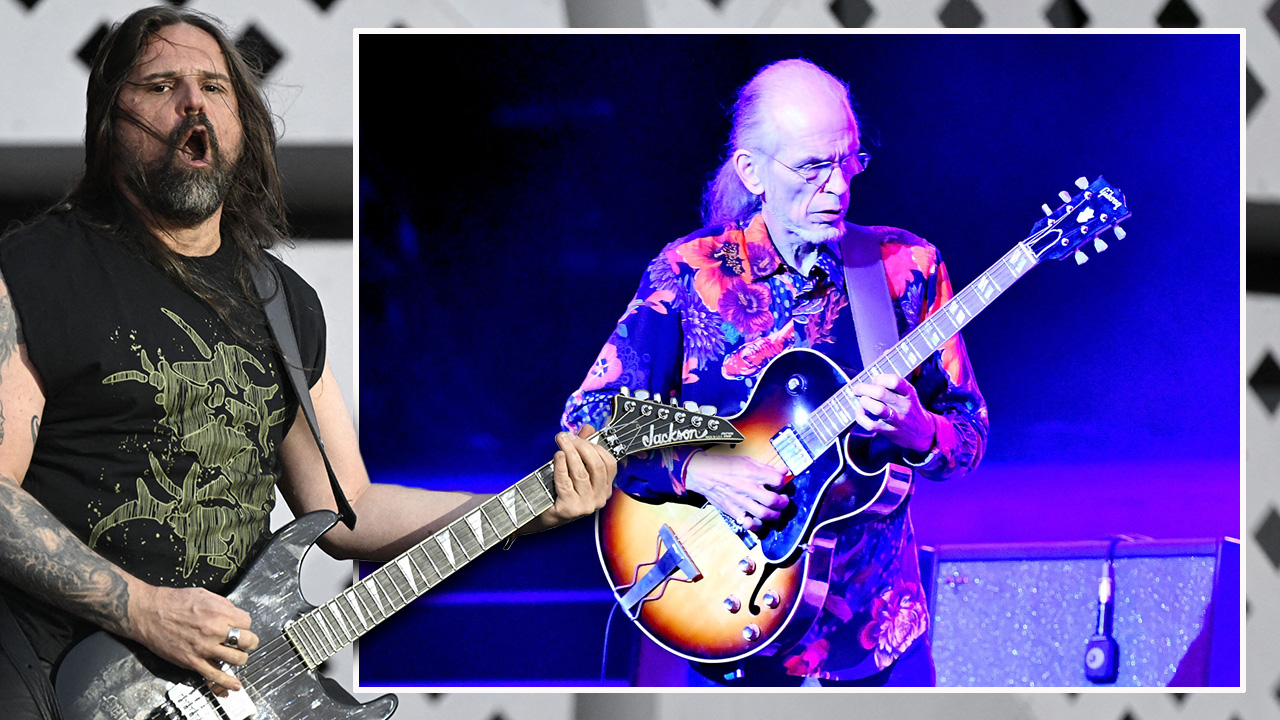

Kilbey compares The Church to Pink Floyd in the sense that everyone has an equal, fixed role. “I’m the minister of philosophy and esoteric ideas, Peter [Koppes, guitar] is the minister for musicality and Tim [Powles, drums] is the minister for production and recording and microphones, with Ian [Haug, guitar] as the new guy contributing where he can.”

Kilbey doesn’t actually believe The Church deserve a place in the pantheon alongside the Gods of Rock, but he is happy to be an apostle. “I don’t think we’re the best or most brilliant band of all time, but we’ve had some great moments. Now that the Floyd aren’t making records and Lou Reed’s dead, if you like those records, here are some disciples who are carrying on.”

Finally, out of all the epithets and genres ascribed to his band over the years, which does he think best fits? He allows himself a brief moment of messianic glory. “One great thing Jesus used to say: ‘I am whatever you say I am.’ I think that’s the way to answer that question.”

Further/Deeper is out now on Unorthodox. See http://www.thechurchband.net for details.

YOUR SHOUT

They came from the land down under, where women glow and men chunder… But were The Church prog? “They were (and are) very prog. This is the band that released an entirely improvised instrumental album, after all. They frequently turn in 10+ minute tracks, they often subvert song structure & swap instruments. Also, Steve Kilbey’s lyrics are weirder and more wonderful than anything most prog writers have ever come up with.” Dave Cooper “Not very prog at all.” Ray McCabe “1 on a 10 scale!” Harald Bjervamoen “Most of the albums they did in the 90s were quite proggy.” Thomas Gitopoulos “On a scale of 1 to 10? Hmm… Zero!” Mark McCormac “Nice one. In a scale of Slade to Keith Emerson… Kong!” Louis Botton “I don’t think The Church have a progressive bone in their body. And I really liked them back in the day, but haven’t listened to them in years.” Kevin Salyer “At the beginning not prog at all, just beautiful, atmospheric, new wave church music. Later it became more prog. The latest album is quite prog.” **Kari Hautakoski ** “The Church have some atmospheric elements to their music (for lack of a better word), so I’d say that they were just a little bit prog.” **Todd Evans ** “The Church became prog around Gold Afternoon Fix. They’ve gotten massively more prog since. Further/Deeper is their proggiest yet and also brilliant.” Eric Sandberg “The Church are a little bit prog/concept. Always great lyrics. If you like prog you would likely love The Church. I am a qualified Australian and therefore know these words to be true. Checkout Priest=Aura.” **Richard Polden ** “Their music is melodic and emotional, but not in a prog way. Great band though. I have every one of their more than 20 albums.” Inge Kuijt Hardly “Priest=Aura is a slightly proggy masterpiece.” Adam Kullén “Afternoon Church had some prog like tendencies but I would say it is very good rock music. Unlike Talk Talk that actually progressed, The Church stayed more or less on the same course. Good stuff though.” Dave Fulton Gold “Just checked them out on YouTube and I would site them more as alternative than prog.” **Daniel Black ** “Who?” **John Miller **