"All this is worth it!" - The Pineapple Thief and Your Wilderness

Bruce Soord tells how he overcame extreme stage fright to push The Pineapple Thief onwards to album number 11

Bruce Soord used to get terrible stage fright. The sort of crippling sense of dread and panic that partly explained why his band The Pineapple Thief only used to play a handful of gigs a year. It manifested itself as a nagging, foreboding tension deep in his stomach that only got worse as stage-time approached. It provoked the sort of existential crisis no performer wants to go through. “You think, ‘Why am I doing this? Why am I touring? Why am I going on stage?’” he says today. “It’s horrible.”

All that changed a few years ago when TPT were booked to play a festival in Germany. It was one of the biggest shows they’d played to date. “I don’t know how our agent got it,” says Soord. “It was a mainstream festival. Before we went on, there was this ‘Whooah-oah-oah’-type band playing, and everyone was into it. And we were following them with our prog rock. I was at the side of the the stage going, [puts face in hands] ‘Oh god.’ And we went on and fucked it right up. It went down like a lead balloon. Someone even threw a bottle at me. That’s the only time that’s ever happened.”

When the band came off stage, they knew something had to be done. They were booked to play another festival a couple of weeks later, and Soord knew that if that happened again, then “that would be it, it’s going to be over”. He decided to take drastic action. He decided to tap into his inner rock star.

“The next gig I went onstage and just went ‘COME ON!’ It was, like, ‘Fuck you, I’m Bruce Soord, like it or fuck off,’ rather than [apologetic voice] ‘I hope you like it.’” He smiles sheepishly. “It sounds really cheesy.”

He’s right: it does sound cheesy. But it worked. He got over his stage fright.

Soord makes for an unlikely rock star. Sprawled on the bed of his hotel room, the day after The Pineapple Thief’s headline appearance at Barcelona’s Be Prog! My Friend festival, he looks more like a typical Englishman on holiday: stripy T-shirt, scrawny legs poking out the bottom of his shorts (although his tan is surprisingly healthy for someone who describes themselves as “a bit of a studio nerd”.) In truth, he doesn’t carry himself like a rock star either. He’s unfailingly polite and thoughtful, and always seems on the verge of apologising for something, even when there’s nothing to apologise for.

But 18 hours earlier, a rock star is exactly what Bruce Soord looked like. Onstage at the Be Prog! My Friend festival, backed by a vast screen that pulsated with colour, Soord was magnetic. Restless and electrifying, wrangling his guitar like it had a thousand volts pumping through it at any given time, this was as far away from prog’s usual introspection as it gets. His face lights up at the memory.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“When we came off that stage, we were, like, ‘Why can’t we have this more often?’ We’ve paid our dues. We’ve toured the shit holes in a crappy bus, playing to 50 or 1000 people. You’re just chipping away at the surface when you do that. But this felt like going to another level.”

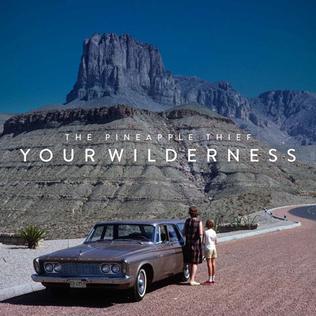

Its ironic that Soord has stepped up to the plate just as his band have made an album that delves into their prog past. Where 2014’s Magnolia was a brazen and unashasmed rock record, the follow-up Your Wilderness – their 11th album – is all moods and textures. It’s a 21st century prog record for sure, but a prog record it undeniably is.

“I grew up listening to prog, but also to mainstream rock,” says Soord. “And for the last three Pineapple Thief records, we tried to crossover to rock.I think a lot of people heard it who weren’t into prog rock really loved it, but a lot of people in the prog rock world have gone, ‘This isn’t prog!’”

So has he backpedalled with the new album? He laughs.

“No. I felt like I’d written those rock songs – if I tried to do another Magnolia, it would have been the same songs but not as good. So I said to the guys, ‘I’m going to remember what used to excite me when I was a kid growing up in the 80s, which was prog rock.’ So I put myself into the mindset of having a prog rock attitude.”

Which is what?

“Not giving a fuck what people think. Or that it’s OK to have play notes on a guitar longer than you would in a rock song, before the money shot comes in. It’s our 11th record. I can do whatever the fuck I want.” As soon as he says it, he looks a little sheepish.

A few things have changed for Soord in recent years. He released his first solo album in 2015, a record which was inspired by his love of Beck (“Half of my brain wanted to take the songs in a direction that wasn’t The Pineapple Thief, so I decided to take half my brain and put it over there, and that was the solo album”), collaborated with Jonas Renske of Swedish doomy prog metallers Katatonia on The Wisdom Of Crowds (“He loves singer-songwriters, which you wouldn’t guess to look at him”) and began to remaster other band’s records, most notably the reissue of Opeth’s Deliverance. But the biggest change in Soord’s life was that he finally got chance to quit his day job in IT and take up music.

“It always felt productive,” he says. “You spend seven hours a day doing something you don’t want to be doing while your brain wants to make music. When you get home, you’ve got so much energy: ‘Come on, let’s write this song!’ Weirdly, going full time, that’s gone. I remember thinking, ‘I’m going to have so much spare time that I’ll be able to write 10 albums a year. It’ll be so easy.’ But it isn’t. Even with this album, it was hard to get started. You should be careful what you wish for.”

If he sounds downbeat, he’s not. Seventeen years into The Pineapple Thief, and Soord has carved out a niche for himself alongside the Steven Wilsons, Anathemas and Opeths of this world. But is he happy where he finds himself these days?

“The stock answer is that I’m really grateful that we’re where we are. Commercially, I wish that more people knew about us. It’s not about the money, although the money would be nice. The thing that frustrates me is that so many people haven’t heard of us. I don’t know why that is. We’ve been around for 17 years, and seen people like Steven Wilson and Opeth break through.”

How have they managed that where The Pineapple Thief haven’t?

“The difference is that they really busted their arses touring. I didn’t do that. I guess you get what you deserve. I stayed in my studio, stayed in my day job, writing records, and I wonder if you can break through if that’s what you do.”

You tell us.

“I don’t know,” he says. “We’re on an upward curve, but we haven’t made the breakthrough. We’re burrowing our way to the surface.”

Is this down to lack of ambition? Or lack of hunger?

“I think that I was quite ambivalent when it came to taking that risk. I fell into that comfort zone. I said to my wife, ‘I just want to make music – I’ve got my day job, we’re doing 10 gigs a year.’ And you’re never going to breakthrough doing that. What we should have done is bet everything on this album, doing a loss making support tour and just going for it. But you don’t know that at the time.”

At the Be Prog! My Friend festival, Soord looked like he was truly enjoying himself, and there was the whiff of the Matt Bellamy about him in his slightly skew-whiff guitar heroics. And while prog has never had much truck with rock star fripperies, it has had its characters, fron Daevid Allen to Rick Wakeman to Peter Gabriel and his wardrobe of weirdness. The question is: does Bruce Soord fancy himself as

a rock star?

“No,” he says, wincing slightly. “It’s very awkward for me. Mike from Opeth is very similar. He doesn’t court that. He doesn’t want to be put on a pedestal. Sometimes I feel like a rock star. But then I feel guilty about it.”

But isn’t being put on a pedestal part of the job of being a musician, prog or not. Peter Gabriel, Jon Anderson, Fish from Marillion – they all embraced that aspect of things.

“[Unconvinced] Yeah. We used to get people coming up to us after gigs going, ‘Oh Bruce, your last album was amazing. And I’d be, ‘[bashfully] Oh, no.’ And my keyboard player came up to me and said, ‘People don’t want to hear that. They want you to be that man they’ve heard on the record.’ That was when I realised, yeah, maybe there is part of me that needs to embrace that. I do enjoy seeing the impact what we do has on people. At the gig last night, I said to Jon [Sykes] the bass player: ‘I can’t believe we’re doing this. This is an extraordinary experience.’ Because it’s a positive impact.” He laughs. “Just not for my ego.”

He’s right. There’s no obligation for anyone to start behaving like Bono. But as Soord has grown more confident onstage and off, you can’t help wondering why more musicians aren’t stepping up to the plate or even stepping out of the insular confines of the prog scene. Even Steven Wilson – one of the big success stories of the 21st century – is still largely preaching to the converted. He’s broken through, but he’s not broken out.

“It’s certainly very easy to stay in that comfort zone,” says Soord. “You know if you pander to that crowd, you will sell records. But what do you do? When we did Magnolia, we had really high hopes that it would resonate with people in the wider world. Artistically, I think it worked, but there weren’t that many people who were prepared to go out and seek out new music.”

Does the fact that you haven’t broken beyond the boundaries of prog get you down?

“Yes, in a way. When people ask me what my expectations are, I go: ‘I haven’t got any.’ And that probably sums it up.”

If he seems defeated, he shouldn’t be. The Pineapple Thief aren’t that far away from doing a Steven Wilson and taking their music to a wider audience. And if they don’t, well, Bruce Soord will lose sleep – but not that much.

“Yes, we’ve got our 11th album coming out and, let’s face it, we’re still in the prog underground,” he says. “But at the same time, I’m quite rare in that I’m still doing it. That’s why all this is worth it.”

This article originally appeared in issue 69 of Prog Magazine.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.