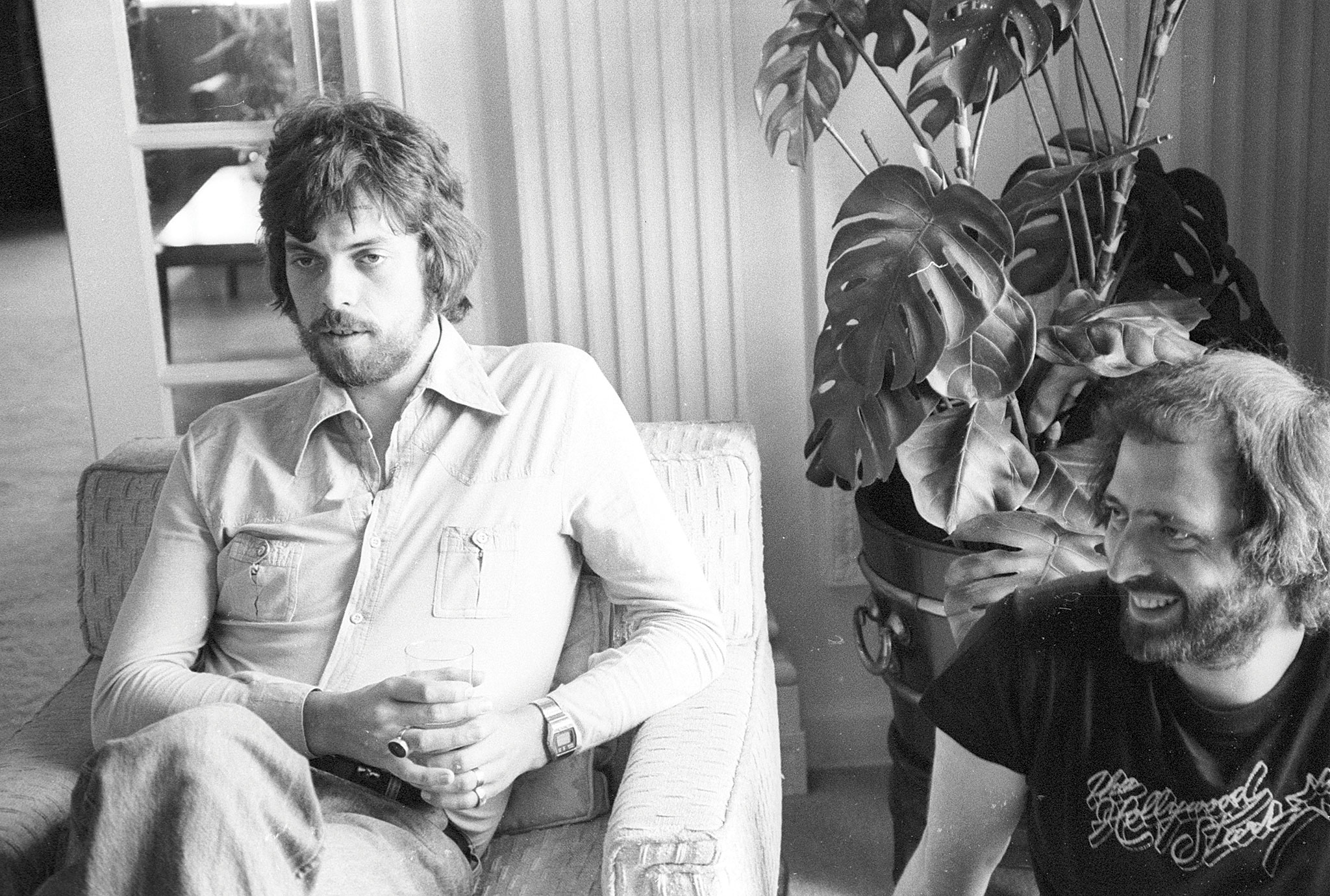

When Alan Parsons walks into the lobby of his London hotel on a recent visit from his adopted home in California, he carries a sheaf of papers and a bag of recordings from another day of his latest masterclasses and talks at Abbey Road.

Talk about being back in the office. Since he first ventured there as a teenager, the historic temple of sound in St. John’s Wood has been part of the great British producer-artist’s very being, for the better part of half a century. He returned there late in 2015 to impart his wisdom to eager acolytes, in both Master Class Training Sessions and Sleeve Notes: From Mono To Infinity talks.

One of the masterclasses was with Belgium’s Fish On Friday, featuring seasoned British bassist Nick Beggs. During their visit, there was a genuine surprise visit from Alan’s old friend Nick Mason. Fish On Friday have now confirmed that Parsons will collaborate with them on their fourth album.

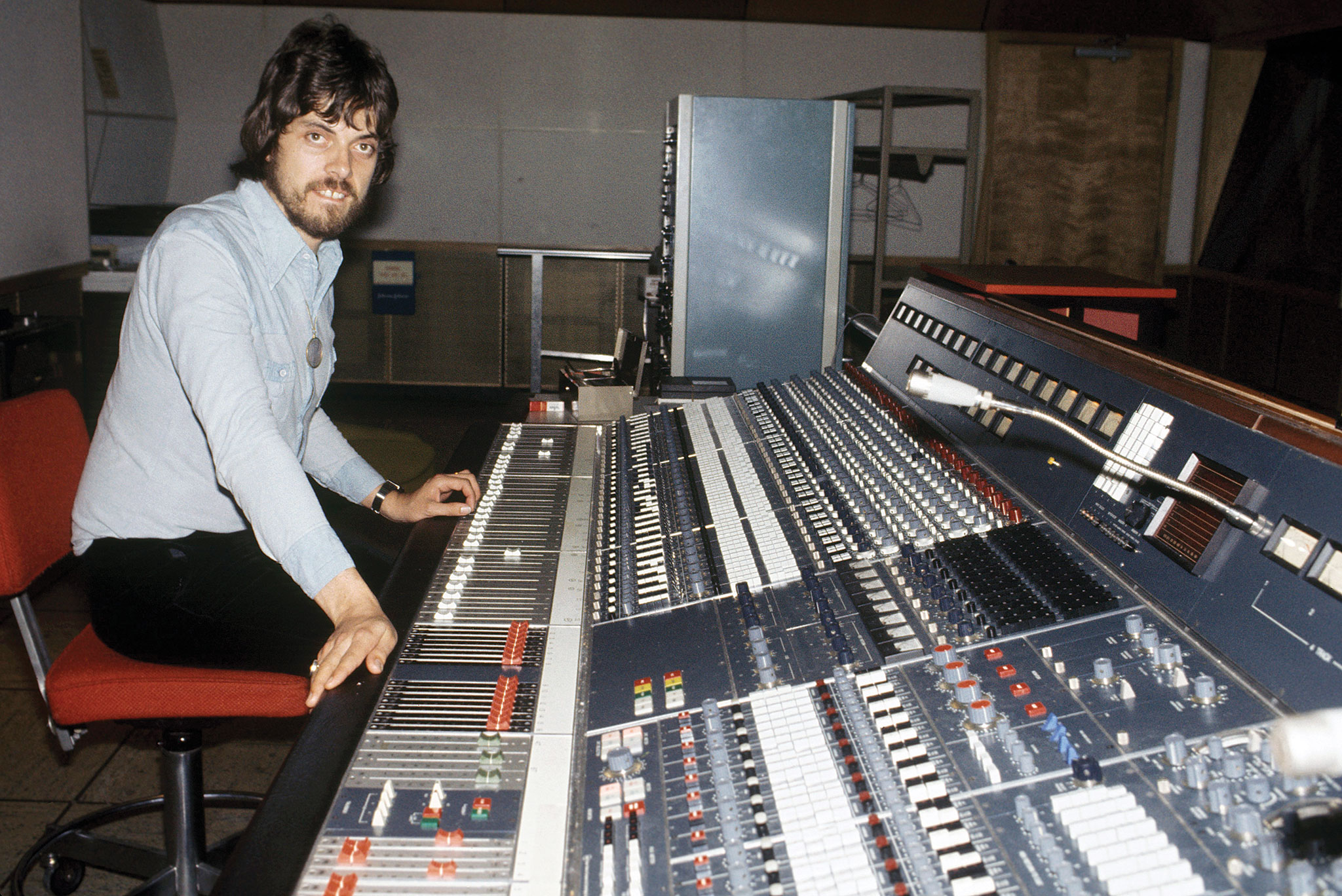

The sessions afforded a paying audience the opportunity to watch the great man at work in the very place where he famously got started with The Beatles and Paul McCartney, engineered Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon, produced Al Stewart’s Year Of The Cat and then teamed up with the late Eric Woolfson to create the groundbreaking grandeur of The Alan Parsons Project. Never envisaged as a live entity in their recording heyday, the latter‑day APP now tour regularly in North and South America, and in Europe.

Work done for the day, save for addressing the inquisitiveness of a Prog reporter who played his copy of Tales Of Mystery And Imagination into submission in 1976, Parsons retires to the hotel’s club lounge, where we will later be joined by his charming American wife Lisa. Here, the question randomiser will land variously on the latest APP deluxe anniversary reissue, his work on some true landmark recordings of the past 45 years, his Beatles and Floyd memories and his lesser-known days as a teenage guitar frontman playing at the Coffin Club.

So how was it being back in your old manor once again?

It’s a real thrill to go back to Abbey Road – it’s hallowed ground for me. I’m getting a kick out of it, to be back there and seeing the old faces. Most of them have gone, but one or two are still there. Collette, the bookings manager, she’s retiring. I can’t believe it. She was a pretty young 23-year-old when she started. Not that she’s any less pretty now.

What do people get when they enrol for one of the talks or masterclasses there?

[Music writer] David Hepworth asks me certain things, and there are audio and practical demonstrations. We’re showing the ‘before and after’ of [Pink Floyd’s] Money loop with separate bits of tape, and with the edits. The masterclasses are recording sessions and they cost a lot more for people to attend. It’s a lot of studio owners, and people who just have a genuine interest in watching a recording session and perhaps haven’t had the chance to do that before.

We start off the day by introducing everybody, because everybody has a certain amount in common, and most people have some kind of recording facilities. Then I say, “Please, I encourage you to pitch in ideas, to say things, and give this band the worst possible nightmare they could ever imagine: 20 producers.”

I had a great relationship with Pink Floyd, and they seemed to respect me. I certainly respected them. And they were all getting on with each other.

Those of us who’ve been lucky enough to spend time at Abbey Road still sense that unique aura about the place. You must feel that more than most.

Absolutely, and that never goes away. Even when I was there 365 days a year [Parsons was briefly VP of EMI Studios Group in the late 1990s], it was like “Wow, this is where it all happens.”

Were you worried when EMI was being divided up that Abbey Road might be sold?

Yeah, that was worrying. There was a rumour that Andrew Lloyd Webber was going to buy it, all kinds of funny rumours. But I think it’s okay now. It’s a shrine.

I remember being there for a birthday party for the studios – I think it must have been its 75th anniversary – and you were there.

Yeah, and Norman Smith [‘Hurricane’ Smith, the Beatles’ original engineer and early Floyd producer] was there. I knew him quite well. He kept friendly with Paul, when Paul and I were living pretty close to each other and socialising. I remember Norman saying, “I think at 30, I have the experience necessary to know what I’m doing in this business,” and he was probably 48 or something at the time!

He had a spell in the early 70s as a pop star, of course, with Don’t Let It Die and Oh Babe, What Would You Say.

Yes, he was fulfilling a dream, and he wanted to do that. He kept doing Beatles covers and failed at that, then in the end made it with one of his own songs.

Where were you living when you joined Abbey Road?

I was in a one-bedroom apartment in Hampstead, one of those converted rooftop flats, with a window that stuck out through the roof.

For a while, you’d had designs on being an artist yourself, hadn’t you?

Yeah, in fact, when I joined the studio, this album, which is about to be released [he pulls out an opulently packaged vinyl disc titled Elemental, by a band called The Earth. Listening to a clip later, it sounds very much of its time, 1968, and is especially reminiscent of Cream], we recorded that just after I started at Abbey Road, at Regent Sound. I hardly ever talked about it. It’s just being released now. I’m the lead guitar player.

It’s never been released before? How has that come about now?

The singer, a guy called Ian Harris, who was going through hard times, discovered that he had an acetate of the album, called the label and said, “I used to be in this blues band in the late 60s. We made an album, it never got released, are you interested?” And they jumped at it.

So you were a guitar figurehead for a minute?

It’s very bluesy – that was what I was into, and a lot of people were into. It was that 1967-’68 blues boom. Fleetwood Mac, with Jeremy Spencer, and John Mayall – I followed all the various incarnations of his band. I always remember with John, the compulsory stage breakdown: “Sorry, we’ve got a little breakdown on stage. I’m just going to play some harmonica.” Happened every night.

What happened to The Earth?

Basically, when I got the job at Abbey Road, I knew it was only a matter of time before I’d have to give it up because I needed to be available, and I was happy to do that. We already had this offer on the table to make an album – I’d literally been there a matter of weeks when we made it – and then I said, “Sorry guys, love the album but I can’t afford to do this any more.” I certainly wasn’t making any money at the time. I played in this dungeon of a place in Gerrard Street called the Coffin Club, a basement. It was a good name for it. I think we got paid £10 a night to play there.

Can you remember the first time you set foot in Abbey Road?

I was 19, and yes, I remember it distinctly. I was granted an interview. I think maybe a year earlier, I’d walked up the steps and seen the commissionaire, who was right there in the lobby. “Any chance of having a look around?” “No, sorry, we don’t do tours,” so I wandered off with my tail between my legs. But then I was already working for EMI at this place in Hayes, and I just chose the right time as the manager wanted to fire two people. I started and two people got fired so I was little bit unpopular for the first little while, until people got to know me, because they were enormously popular guys. One of them was John Smith, who did all the assistant engineering on the White Album.

Quite a difficult start, then?

Yeah, but I considered myself extremely lucky to have been in an associated department. It was literally a personnel transfer – it wasn’t taking a new job or a new contract. The letter said, “Dear Mr. Parsons, please apply for a transfer to the studios.” [Laughs] So that was what I did.

Your work on the last two Beatles albums followed soon afterwards.

The first experience was the Apple sessions, leading up to the rooftop [gig]. So I was just there to help. They didn’t have any tape ops; they hadn’t employed anybody. On top of that, they didn’t have a studio that worked, so they went to Abbey Road to say, “Help, bring some gear down, we’re trying to make a film. Oh, by the way, we need a tape op.”

Were you on the roof?

I was on the roof, yeah. There are shots of me on there.

Did you get to know The Beatles?

I can’t honestly say I knew any of them at that particular time, and Paul [McCartney] is really the only one I did get to know, through his solo stuff and socially.

How about the Floyd?

Yeah, we got to know each other really quite well during the course of Dark Side, and touring. We had a great relationship and they seemed to respect me. I certainly respected them. And they were all getting on with each other.

You met Eric Woolfson soon afterwards. What an unusual guy he was — he’d already had a remarkable career on both sides of the business, as both a songwriter and businessman. How many other groups had one half of their creative centre who was also their manager?

We were a 50-50 relationship. Eric had a reputation of selling the Eiffel Tower to the French, more than once. He was a good dealmaker, especially the very first deal, for [The Alan Parsons Project’s 1976 album] Tales Of Mystery… That was done at [the annual music trade fair] Midem. The head of the label, his name was Russ Regan, literally signed a blank cheque. There were no demos, just the concept of the Edgar Allan Poe album.

So he’d never heard anything?

No, we did the deal, the money came in and we had all the money we needed to make the record. And, it seems, a little left over, because Eric went out and bought a Rolls Royce, almost the next day! I didn’t. He pulled up in it to my humble flat in Hampstead. I remember John Miles doing the same thing as soon as Highfly hit the charts – he went out and bought a Roller.

Did you know what the sound of Tales Of Mystery… was going to be before you made it?

Only that I knew it was going to be heavily orchestrated and big‑sounding, I knew I wanted that. We wanted to instil the emotions that film-goers got from an Edgar Allan Poe story. Then there was a slightly more mundane purpose that Eric came up with, which was from his accountancy background. He found out that no movie based on a Poe story ever lost money. “Ooh, maybe we can apply this to the music.” Always the businessman.

It was literally a personnel transfer, it wasn’t taking a new job or a new contract. The letter said: ‘Dear Mr. Parsons, please apply for a transfer to the studios,’ so that was what I did!

This is a question you probably get asked every day: do you have a favourite Project?

It’s the first one, it always comes back to the first one. New baby, first-born child. And I possibly had a couple of sounds in my head that I wanted to get out there, and that was the beginning of that sequence of events, that big ‘orchestral with rhythm section’ sound that arguably hadn’t really been done. The only other group around at the time was the Moody Blues that had really used orchestra in a big way.

The reissue programme of original Project albums recently landed on the 35th anniversary repackaging of the fifth record, 1980’s The Turn Of A Friendly Card. With the extra disc of early versions of songs, isolated backing vocals, single edits and bits from Eric’s songwriting diaries on cassette, it’s pretty exhaustive, isn’t it?

[Laughs] Exhaustive, yeah, and I have to say exhausting! But if you’re a keen Project follower, it’ll give a little bit of insight into what went on. There are plans afoot to put out Tales Of Mystery… again as another anniversary disc, but that hasn’t really started yet – they’re concentrating on this one. There have been reissued versions of all the albums now, but this is the first double disc, apart from Tales…, which had its deluxe reissue with both the original mix and the 1987 remix. Everything else has been single CDs.

The material has been compiled for reissue by Eric’s daughter, Sally Woolfson.

Yes, she runs the estate so she’s the businesswoman that filled the place Eric had, dealing with publishers, labels, that kind of stuff. I think it was always known the cassettes existed but they’d never been visited properly and transferred. Who’s got a cassette machine these days?!

One of the joys of hearing …Friendly Card again is that it turns the spotlight, sadly posthumously after his death in early 2015, on the terribly underrated singer-songwriter Chris Rainbow, who’s one of the featured vocalists.

That was terribly sad. What an amazing talent he was, and an incredible sense of humour – we would be in stitches. Did you know that he had a speech impediment? Quite a serious one. When he was struggling to get a sentence out, I would joke with him, “It’s very easy for you to say that…” He laughed. He was a bit of a loner. He actually produced a very successful Scottish band, Runrig.

Chris was part of that incredible ‘cast’ of featured vocalists that you built up over the years from the very beginning of the Projects, including people like John Miles, Colin Blunstone, Allan Clarke, Steve Harley, Lenny Zakatek, Terry Sylvester…

It was a combination of people we knew and people we thought would work. I obviously worked with Terry with the Hollies. Colin was a drinking partner of mine in Hampstead. And Pilot became the rhythm section. Sadly, the keyboard player [Billy Lyall] died, AIDS related, but the rest of the band stayed on forever.

One of the greatest cameos, and an inspired piece of casting, is of Arthur Brown on The Tell-Tale Heart from Tales Of Mystery…

I had no connection with Arthur whatsoever, but I think we found a contact that did, and went for it. I was sincerely quite worried that I’d made the wrong choice because he came in and listened to the track and started humming the tune: “Ah yes, I see how it goes. You want to give it a go?” And then he goes out there and just becomes The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown. Until that moment, he’d just been Arthur.

It’s surprising the way The Alan Parsons Project has become such a live attraction when you never toured the original albums at all.

Yes, it’s interesting to note that I’ve been out there doing live shows for 20 years now. It was never the intention for it to be anything other than a studio outfit. I never thought it would come to this – I thought it would all end at the Try Anything Once period [his solo album of 1993]. But we’ve managed to keep going, and of course it’s bread and butter now because with the declining record sales, it’s paying my mortgage.

That’s like 180 degrees from the old days, where tours sold albums.

Yes, which is why labels want 360-degree deals now! But the band has evolved and grown. It started as a five-piece, then a six‑piece, then seven and eight.

How did you find playing the London show at Shepherd’s Bush Empire last summer?

It was good to be back – we hadn’t played in London for some time, and most of the band had never been to London. We just added a new member, Dan Tracey, who’s an excellent singer – he really helps the vocal sound. He plays guitar as well.

Do all of the musicians come to the band these days with a good working knowledge of the APP material?

Yeah, particularly Alastair Greene, who’s one of the most recent additions. He has a career of his own as well, with the Alastair Greene Band. I’m very pleased with the way the band work together – they’re all great players. And it’s not just musical ability, it’s the ability to get on with people. We’re a very friendly band.

But also the vocalists need to fit the mould of the original records.

You’re right, it’s just a case of fitting the mould. I’ve never heard anyone complain that my voice doesn’t sound like Eric’s, and that [vocalist PJ Olsson’s] voice doesn’t sound like whoever it is, Allan Clarke or whatever. It’s the songs they go for.

You and Lisa live in Santa Barbara with her two daughters, and many pets. [Alan’s just become a grandfather for the first time.] Are any of the family musical?

Jeremy, my eldest, has always been musical, but he’s becoming more of a technician rather than a musician these days. He would love to get a job at Abbey Road. You can print that! But there’s so many recording schools now, all you have to do is go, “Who’s your best student? Oh, we’ll take him.”

[As we conclude, Lisa wonders why I haven’t asked the question everyone asks, about the supposed synchronicity between Dark Side Of The Moon and The Wizard of Oz. It provides the final punchline to a convivial conversation.]

There’s a standard answer, and I’m using it at Abbey Road – it’ll be the last question. “What is it about The Wizard of Oz?” “Well,” I say, “the legend is there, but they got it completely wrong. It was actually Mary Poppins.”

Alan Parsons’ Art & Science Of Sound Recording – The Book is out now, written with Julian Colbeck and published by Hal Leonard. See Prog 63 for our review and visit Parsons’ website for details .