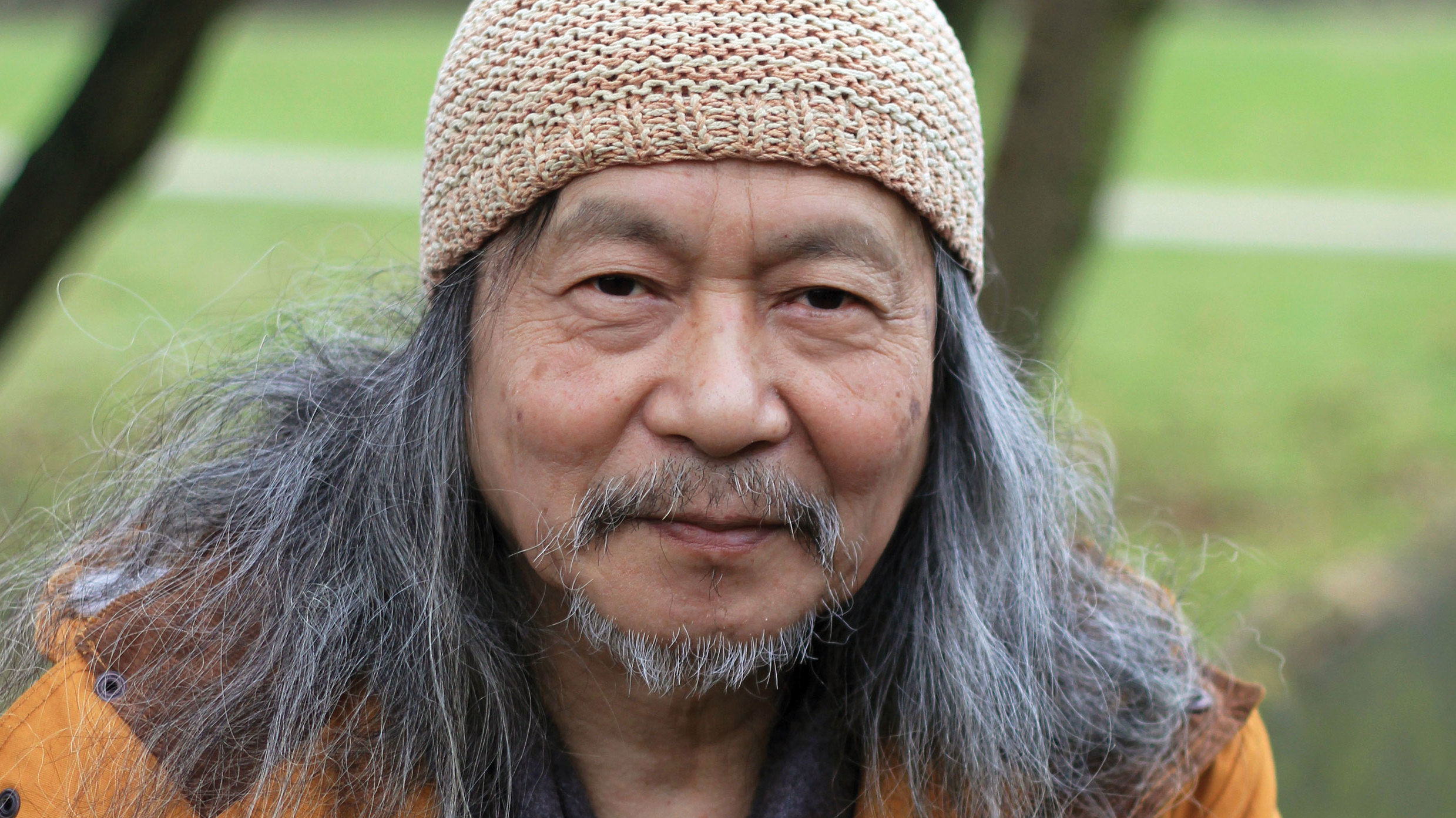

The Prog Interview: Can's Damo Suzuki

Japanese singer Damo Suzuki is best known for fronting German Krautrockers Can during their peak era in the 1970s after being plucked from the street as a busker by the band.

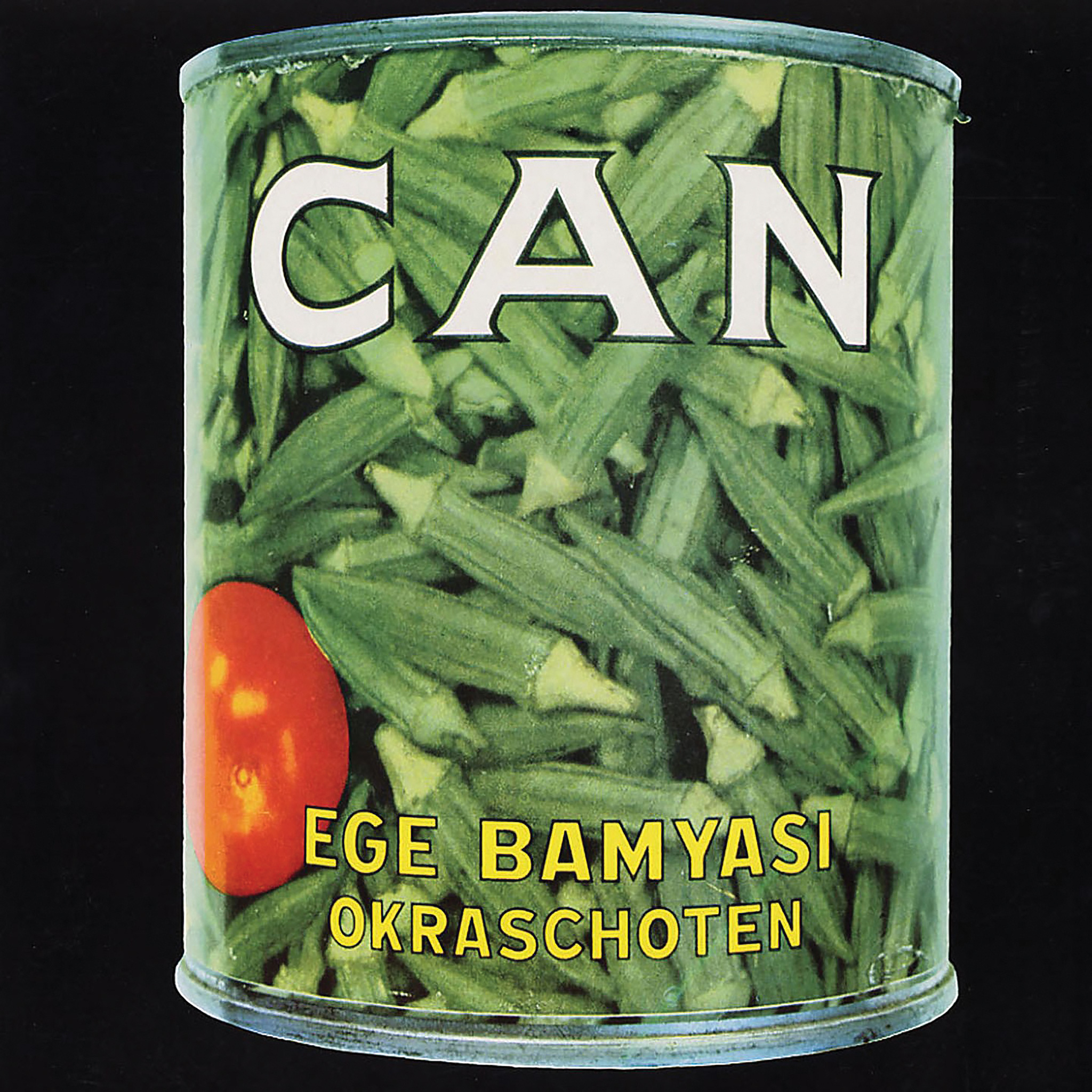

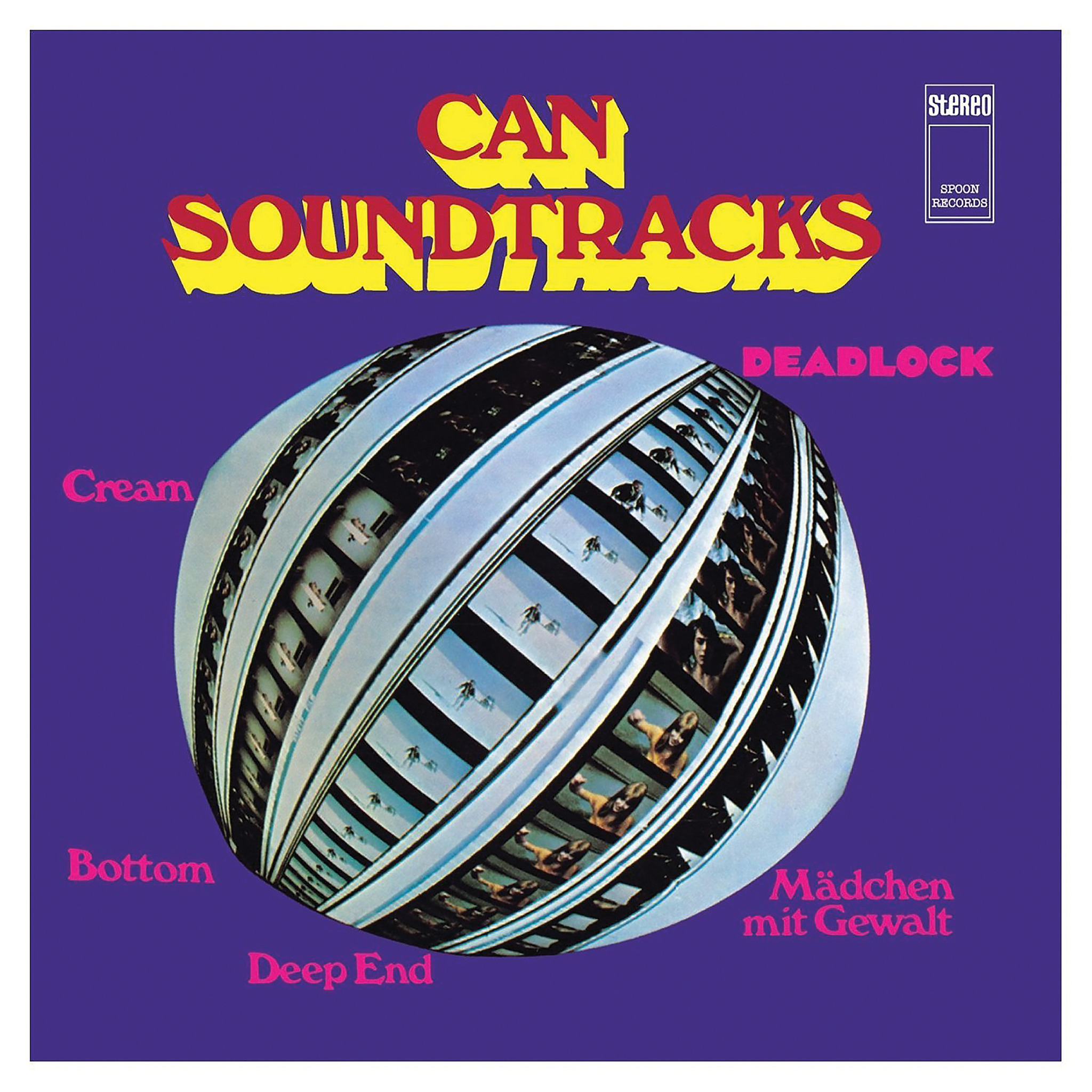

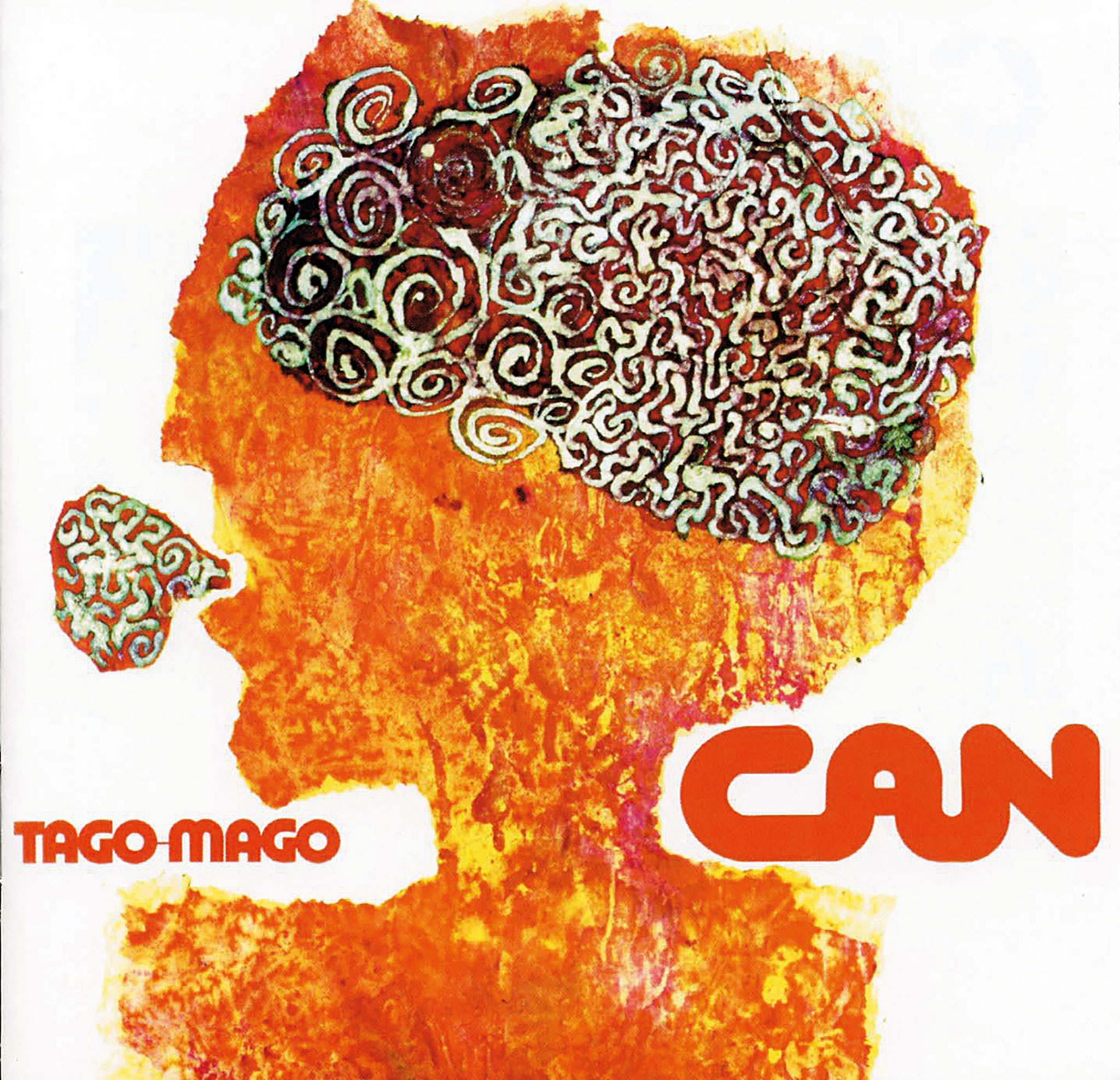

Interviewing Damo Suzuki is a curious experience. Much like his improvised live performances, which he calls “instant compositions”, you’re never quite sure where it’s going next. The only thing that’s certain is his reluctance to discuss Can, the seminal German band he fronted between 1970-’73. It was a time span that produced their greatest albums – Soundtracks, Ege Bamyasi, Tago Mago and Future Days – records that continue to shape generations of experimental rockers and avant-garde musicians.

Past endeavours may belong in the past in Suzuki’s eyes, but his unquenchable appetite for life means that his conversation roams as wild and free as the music he’s made over the past five decades. During an hour-long interview at his home in Cologne, the 66-year-old discusses the forces that drive him, why he never goes near a recording studio, his affection for Hawkwind and The Kinks, plus Brexit, politics and Premier League football (he’s a keen admirer of Liverpool boss Jürgen Klopp: “He’s such a great manager. With a kind smile, very natural”). As it turns out, there’s even talk about his old band.

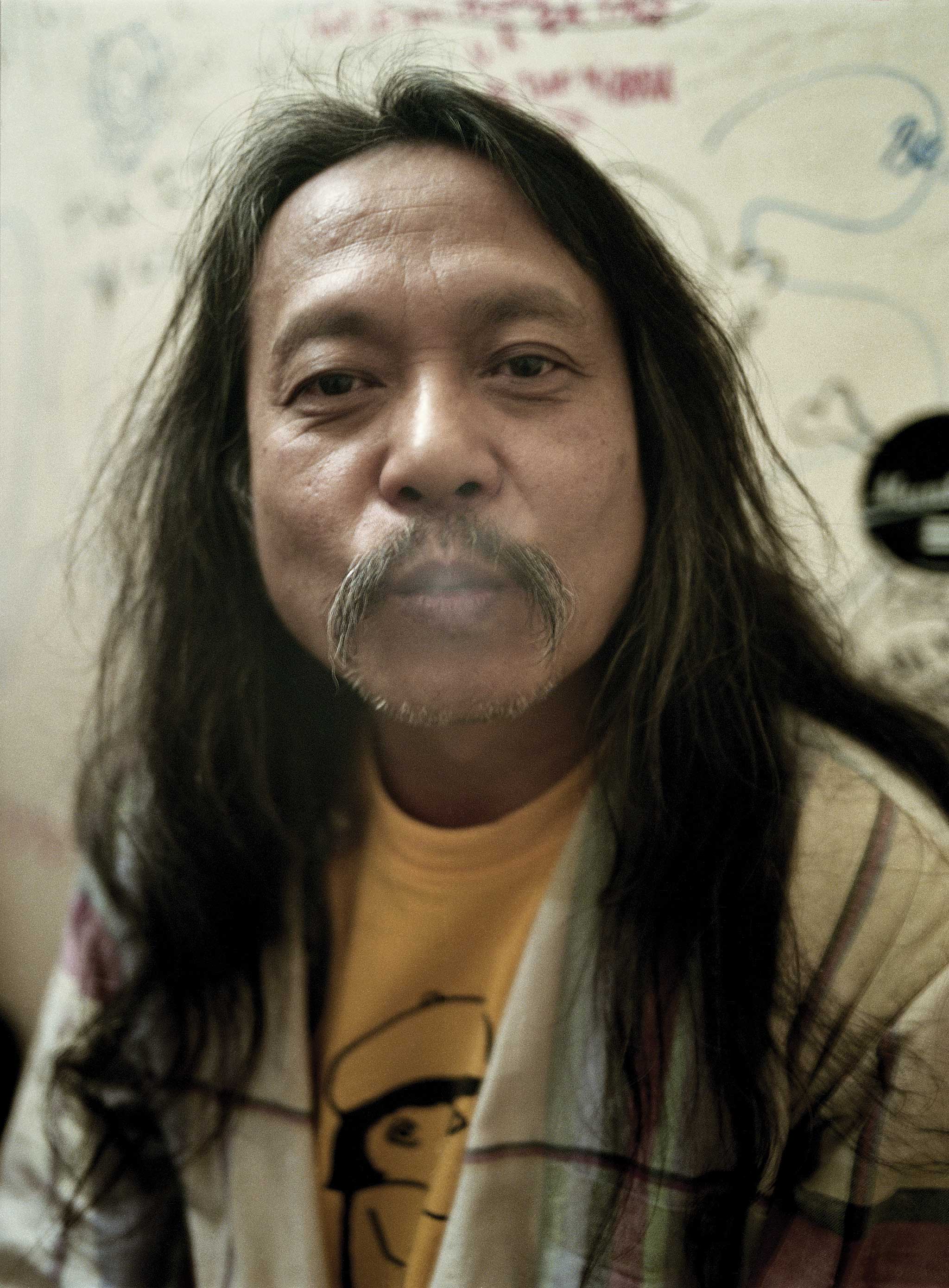

Suzuki was barely 18 when he left his native Japan for Europe in 1968. He briefly formed a folk duo in Sweden, before busking his way through Denmark, France, England, Ireland and Germany, causing a stir with his exotic looks and free-form songs. In May 1970, while performing in a Munich street (sometime after landing a part in the German stage version of Hair), he was spotted by Can members Holger Czukay and Jaki Liebezeit, then seeking a replacement for departed vocalist Malcolm Mooney.

“Jaki and I were sitting in a cafe and saw Damo coming down the street,” Czukay tells Prog. “He was somehow praying to the sun and making loud noises, singing or chanting. I turned to Jaki and said: ‘This is our new singer.’”

Czukay introduced himself and asked if Suzuki might be interested in joining the band for that night’s sell-out gig at the Blow Up club. “I told him there’d be no rehearsal, that we’d see him on stage and he could just go ahead,” continues Czukay. “And it worked out in a totally unexpected way. On stage he started out very calm and peaceful, then suddenly – like a Samurai warrior – he switched and became the exact opposite. The audience were frightened by him. It was like when the Sex Pistols first came out.”

This became a template for Suzuki’s entire career, a spontaneous presence on stage and in the studio, a charismatic figure concerned with living purely for the moment.

Suzuki’s exit from Can was the start of a 10-year hiatus from music itself, during which time he became a Jehovah’s Witness. He returned in 1983, fetching up at gigs by Dunkelziffer and subsequently cutting a couple of albums with the Cologne collective. In 1986 he formed the Damo Suzuki Band, whose line-up included Jaki Liebezeit, before eventually founding Damo Suzuki’s Network, an umbrella label for his live performances with local musicians from all over the world. He calls these improv collaborators ‘Sound Carriers’.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

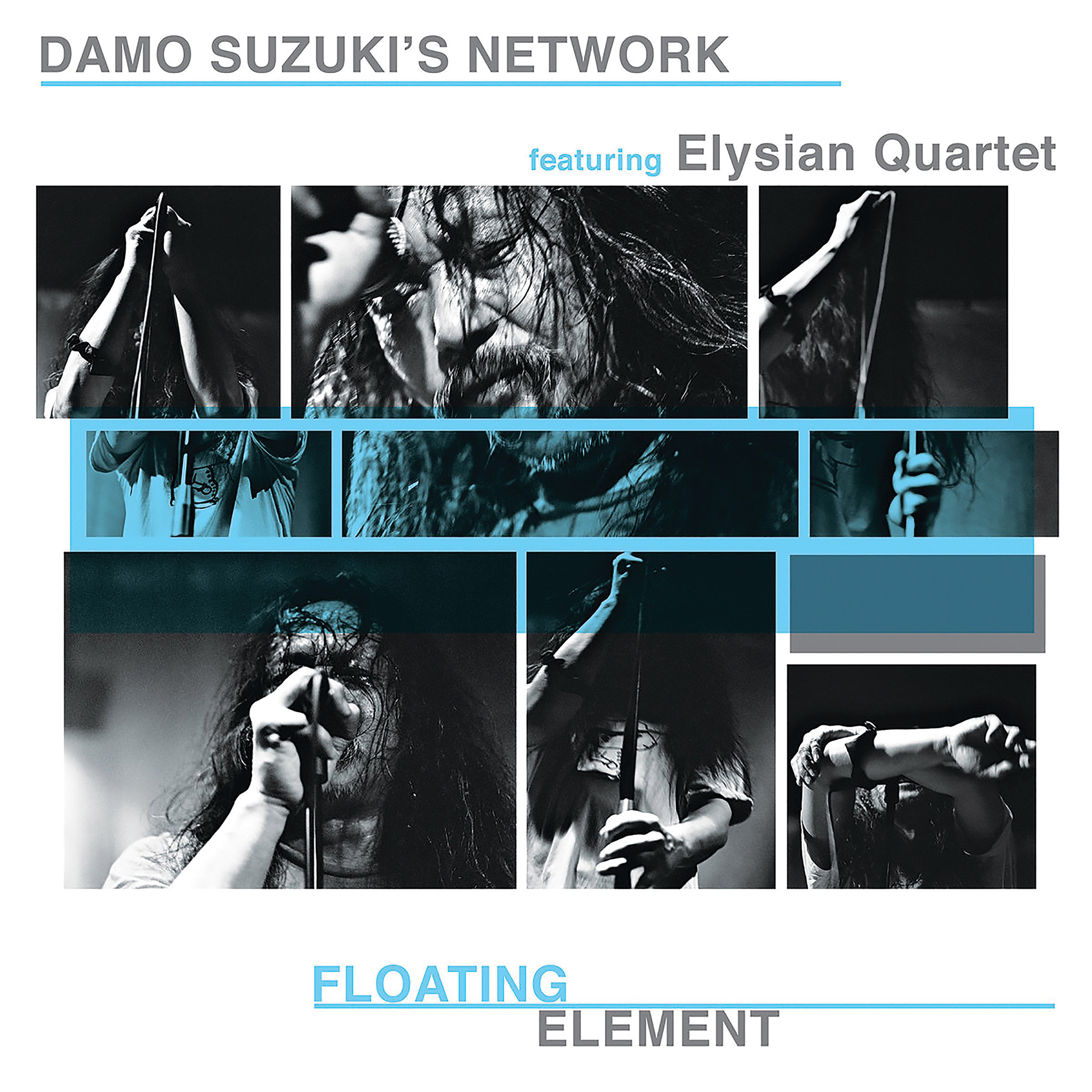

The latest release from Damo Suzuki’s Network is Floating Element, recorded at London’s Purcell Rooms in 2007 with classical string ensemble the Elysian Quartet. A vast collage of moods and textures, it features Suzuki at his extemporising best.

He stopped gigging two years ago, after the return of the cancer that he was first diagnosed with in 1983. Happily though, he’s now back in the saddle…

How is your health now?

It’s okay. I’ve had an illness for the last two years. In September 2014 I was diagnosed with colon cancer. They operated directly and afterwards they found two holes in my small intestine. So my stomach has no muscles, which means I cannot carry heavy things.

That’s why I haven’t done many concerts since then. I’m waiting for another operation later this year, then two or three different surgeries later. In a situation like that, I’ve just enjoyed being lazy and getting enough sleep. But

I did two concerts in August and September, in Germany, before going over to England.

What do you remember of recording Floating Element with the Elysian Quartet?

I always try to do something different in performance, to go a different way to other musicians or artists. It’s my speciality and trademark, really. That night was so special because it was the first time I’d performed in a classical music venue with classically educated musicians. It was totally different from the normal rock formation of guitar, bass and drums. I never talk about the music before the concert so I didn’t know how they were going to instantly compose. Normally, classical musicians don’t improvise; they study notes and have some form of structure. But I didn’t worry about that because this is my occupation. This is the kind of thing I like.

When did you first begin to feel comfortable with your style of instant composition?

I wouldn’t say it’s ever comfortable because every experience is different. Sometimes it’s not really a good sensation because I don’t know the musicians on the stage. The first time we meet is when we play together. I don’t like to have any system or information before I make music. This is a natural way to do it because all music begins this way. Even the Sound Carriers I use on stage don’t know what’s going to happen.

That’s why you go to see Liverpool play football, to hope that they score goals and win. But if you know the result already, then it’s quite boring. For me, music is also like this. That’s one of the reasons why I don’t go into a studio, then go out and play the same thing 200 or 300 times. That’s more like business. It’s really hard for me to act like that.

Can you trace that attitude back to your days busking in Europe?

Yes. Because I couldn’t play guitar and only knew two or three chords, I had to improvise to get some money. It was the end of the 60s and there weren’t so many Asian people in Europe, especially Japanese. So it was strange for people. Also I had long hair and was quite small. They must have thought I was someone from another planet.

I didn’t make a lot of money, but people would be standing and watching. I had many troubles with the police. Many times I was put in jail for one or two days because I’d stop the traffic wherever I was. Police would either arrest me or send me somewhere else.

Had you decided to pursue music as a career by then?

No, I didn’t actually want to be a musician. I wasn’t so much in contact with other musicians – I just liked to visit different countries and meet other people. I was much more interested in the process of studying other human beings, so music was a tool that helped me do that. I made music with local musicians – sometimes country and western players, or experimental musicians, any kind of form – because I didn’t want to make music that had anything to do with current rock.

I like to have many different personalities in my music. Music is communication. That’s why I do instant composing. I’m just trying to live in the moment, which is something you can only do with improvised stuff. It can be a very intense, special moment with an audience, where music is the most beautiful thing. Every day I can express how I’m feeling about living.

How were the British audiences when you first toured with Can in the early 70s?

The audiences were always the nicest in England, much nicer than Germany anyway. That’s the reason why I’ve played far more concerts in England. A German audience is more like when somebody is buying materials in a supermarket or something like that. They’re more orientated in trends and mainstream things. In England, the audience feels more like people buying some special thing in a small shop. They have their own philosophy.

Did the same go for some of the bands you met, like Hawkwind?

Sure. At that time, the music scene in England was totally different from Germany. The musicians were much more open and friendly and easier to communicate with. England was always really good to play.

Did I hang out with Hawkwind for a time? Yeah. Hawkwind were actually more of a German band, much more Krautrock. I knew Lemmy for a while, and also Nik Turner and Stacia. And we had the same label, United Artists. I think we went to a party together somewhere, but I never performed together with Hawkwind. I did perform in concert with Nik Turner this century though. I heard recently that he was making a science fiction movie, acting in it. Someone in the US asked me if I’d like to take a part in it, but I said no. I can’t travel much at the moment because of my health.

And I don’t like to go to the States for many reasons, because they have a manipulative system. I don’t like the police system there, or the politicians and the politics. After my 2007 tour of the USA, I said that I wasn’t so much interested in going back.

Are you a political animal?

I think everybody is political. You can’t escape it, because what happens tomorrow is maybe based on a political decision today. A recent example of that is Brexit. There are no really good politicians here in Germany. It’s quite egotistic, so in the European Union it’s Germany who always decides what happens. And other European countries must follow.

You might be surprised when I say this, but I think Brexit is a good thing. Because this is the form that every nation must take. Actually, I like the idea of the Ancient Greek style of a city within a city – a city nation.

So Brexit wasn’t the disaster many people thought it was?

No, because people must think about local things. If you use local materials and buy local stuff, then there aren’t so many people losing jobs. The economy would be much better. I really don’t like globalisation because it’s based on industry and banks. The major companies, oil companies and the others, try to make a big profit by producing stuff in cheaper countries, like Vietnam or Africa or somewhere else. That’s why I like the idea of Brexit, not just for the UK but for every country.

This isn’t racism – it’s nothing to do with racism. Everybody must be proud of themselves and their local product. We have to support the local community. Globalisation is a complacent way for the world to be.

What kind of music did you listen to while growing up in Japan?

Lots of totally different things, but I began with mainstream classical music, people like Tchaikovsky. Then I started listening to soul and British music. I really liked The Kinks at that time. I even started a Kinks fan club in Japan, before they’d even released a record there.

I used to import their records when I was maybe 16 or 17. Other people would be listening to The Beatles or the Rolling Stones, who were both quite mainstream. I didn’t want to be in the middle of this mass media – it’s not my living standard. So that’s why I went for The Kinks. I could be quite provocative that way.

How did you end up in the Munich version of the musical Hair?

I was living in London at the end of 1969 and didn’t have any money, so I went to Germany to get some kind of job so that I could get back to Japan. During a week when I wasn’t allowed to busk on the street, I went to the local pub in Munich and some girl told me they were looking for an actor or dancer for Hair. I went to the audition and they didn’t think twice, because I had long, beautiful hair. Most of the other people didn’t, so I got the job. There was room to improvise, but basically it was the same thing each day. So I quit after two or three months. I wanted to be outside and that’s where I ended up meeting these people [in Can]. They asked me if I would sing with them that night, at a concert in a big local discotheque.

Have you ever done any vocal training?

I never do it, because it’s not necessary. That’s the medium of better singers than me, who try to do some training every day. If you’re training then you’re learning structure and the system. Then you sound like most music, which is something I don’t like. I just go on the stage as the Damo Suzuki who’s too lazy to train vocalisation and people understand me.

Everybody has a voice and a different technique and so on, so I just try to be me. Being Damo Suzuki is much more interesting than trying to be any kind of the best singer in the world. I don’t listen to other singers for inspiration. Actually, I don’t listen to much music at all.

Did the rock star life ever hold any appeal for you?

I’ve always been anti that. I was never interested in being a star or getting stardom. It’s not being free. If I was to become a star, then I must work together with the people attached to the industry and I wouldn’t get time for myself. There are always lots of appointments and everybody is watching you. You only have to say the smallest thing and it will get into the newspaper. It’s like Big Brother is watching you.

Is that one of the reasons why you left Can? Was the band becoming too popular?

That’s partly correct. At that time we were getting quite famous and we’d be in a teenage magazine or something like that. Also we were sort of having hit songs and I was not so much interested in being involved in that. I didn’t want to be a part of that system. Another reason is because I gave it up for my family. I didn’t want them to see me as a star or be in a famous band. I was only 23 years old when I left Can, so I had so much of the future ahead of me. I didn’t see why I should be chained to the music business.

Was it also partly to do with the fact that you felt Future Days was a pinnacle of sorts?

Maybe, yes. Musically, I was satisfied.

Why did you give up music for the best part of 10 years after leaving Can?

I didn’t want to have any contact with the music business any more. I wanted to develop myself and also just wanted to stay quite silent. It was a really nice time because taking a break for 10 or 11 years meant that it was also part of my life and music. I got to do so many other things. But if I’d stayed in the music business then I would have only seen that world. I was working as a street worker and in a hotel, and also working in a Japanese company, so I had three different kinds of jobs. I could see how the system was working and it gave me a different perspective. It was a learning process.

How had that changed you by the time you returned to music in 1983?

I didn’t want to be involved in a system, like before when I was with Can. I just wanted to be free and make something different. Also at that time, I was recovering from my first cancer operation. Life itself had become much more important than anything else. When you survive such major surgery, it’s natural to have that sensation. People think about their lives much more deeply. I had survived my illness and if some people understood that feeling, then I wanted to make music in a way that I could share my energy.

Did that philosophy also play into Network?

Yes, but Network began around ’97. Between then and 2002, it was always a live performance between friends. It’s been totally different since 2003, when I’ve been trying to make music every day with different musicians.

When bands get in touch to play live with you, do you give them any guidelines beforehand?

Actually, I don’t organise anything. I don’t take any kind of responsibility. A local promoter will organise my concert and direct the musicians from the local music scene. It’s much better that way, more natural. It’s much more interesting if you don’t have any plan or schedule. This is the kind of situation I like to put myself in. If I have the idea of planning something, it always brings stress.

How do you feel on stage?

When I’m completely in the moment I can feel the breath of the audience. We’re all together in one space, creating. Actually, one of the important factors in my music is the audience. That’s why I don’t go to the studio to record anything, because I’m just recording against machines. I’m never nervous before I go on stage. I’m just happy to have the opportunity to make music together every night with different musicians and share this energy with the audience. This is the most beautiful thing I could get in my life. This happens every time, at every concert, so I can enjoy it. Sometimes I’ll be in the middle of a concert and I’ll start crying, because I’m totally happy. It’s still an adventure.

Floating Element is out now on Purple Pyramid. For details, see Suzuki’s website.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.