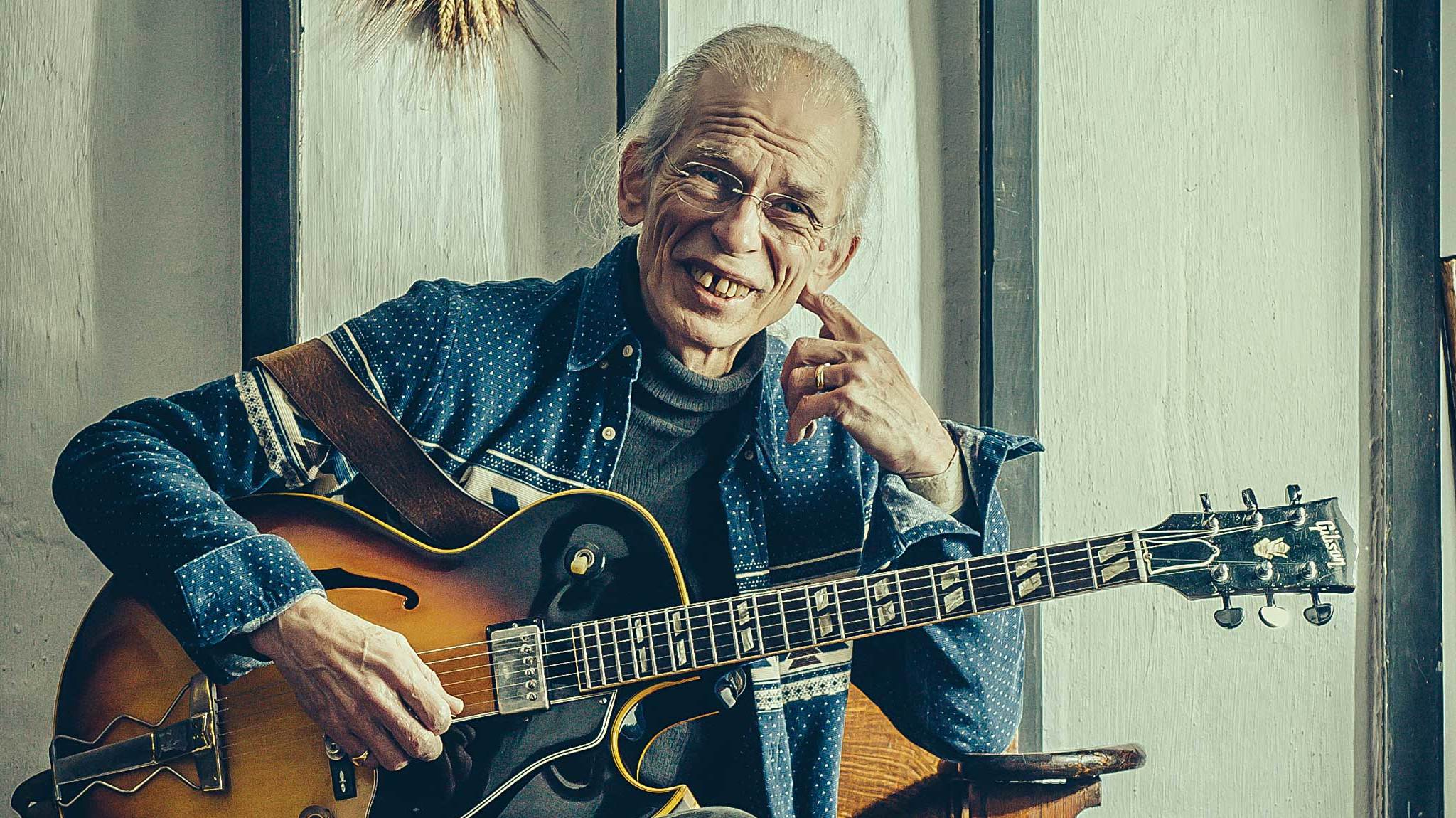

Steve Howe is quick to confess that he’s not someone who can easily sit still.

So just how many make up his voluminous collection these days? “I hate to say but it’s about 100,” he admits with a laugh.

Tucked away in his eight-track home studio, he’s spent a bit of time lately sifting through various concert tapes of the Steve Howe Trio, featuring his son Dylan on drums and Ross Stanley on Hammond organ, for a future live release. “It has more of a proggy element to it, even though we like to swing,” he says. “We’re going to hone down to a final mix and then we’ll look at how we should release it.”

Not that he’s short of things to release. Howe proudly notes that the sixth instalment of his Homebrew home demo series is due to find its way into the eager hands of Howophiles sometime in April. And, of course, he’s continually writing and recording ideas, any one of which might possibly end up on the follow-up to 2011’s Time, his last official solo album, or perhaps as part of a new track for Yes. “I think it is a need that I have, a need to invent music in order to feel that I am a guitarist…”

Heaven & Earth was done in a slightly chaotic way and if people have got criticisms of it, I’ve got no problems with that because I’ve got my own.

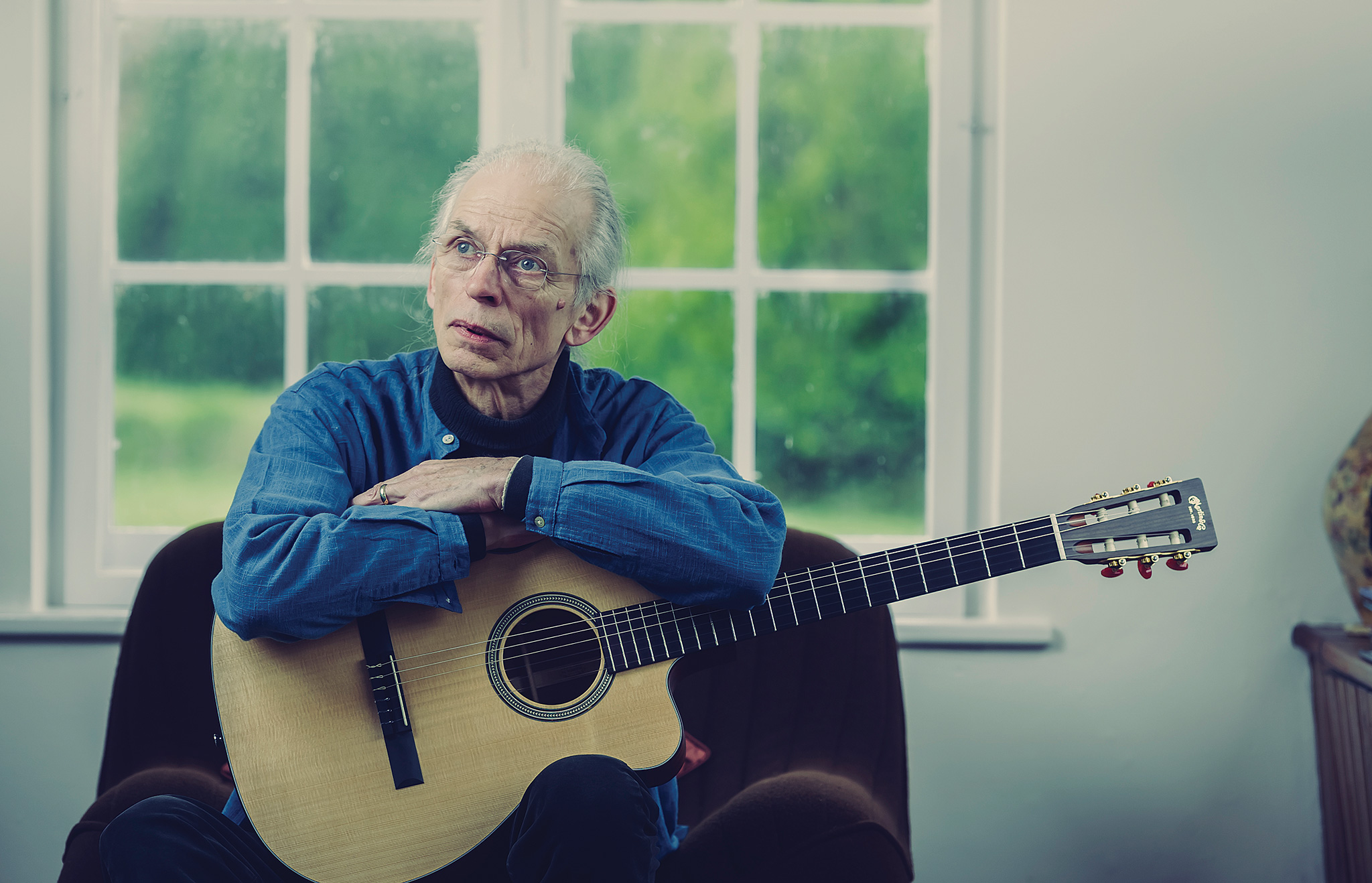

That apparent compulsion, doubling as a means of validating his sense of who he is, hints at both self-deprecation and a surprising vulnerability. That latter notion seems odd when you consider the strength and depth of Howe’s contributions, not only from a technical point of view in the sphere of his chosen instrument, but in the world of rock and progressive music in general. Hailing from an era largely defined and dominated by the electric guitar and the fretboard fireworks that accompanied it, Howe’s unwillingness to serve up reheated, well-worn licks set him apart from many of his blues-based contemporaries. An almost professorial approach to solo construction, encyclopaedic technique and eager embrace of less than obvious influences all form Howe’s singular voice.

Whether turning on a dime from clanging, bell-like tones to hushed, jazz-infused intimacy, his propulsive playing and soaring compositions helped take Yes from the top spot in a provincial polytechnic to filling entire stadiums. Not bad for a self‑taught lad from Holloway.

Prog found Howe at home just as he was about to go off on holiday, but still willing to talk candidly about his career and the band in which he now, with Chris Squire’s passing, represents the last of the original, animating spirit. Howe wouldn’t be comfortable with that description but understands things have irrevocably changed. “What I’ve learnt about bands over these last 10 years is that it’s a lot more difficult than people think. Running a band, keeping it going, organising it and getting the musical satisfaction out of it, takes a lot of commitment.”

Last year, for the first time ever, Yes played without Chris Squire being on stage. What was that like?

Well, it was something we certainly held our breaths about. We didn’t quite know how it was going to feel. The rehearsals went well so we were fairly confident that we had the show together musically. What we didn’t know and couldn’t anticipate was how the audience would feel. There was the feeling of support and afterwards at the meet and greet, as they did all the way through the tour, they said thanks for carrying on. Which is another way of saying, “You’re not doing too bad.”

Did you ever consider calling it a day when Chris became ill?

There was a trying time when we were wondering what to do, but we’d had some dialogue with Chris about him being ill, and needing a replacement so that we could pick everything up when he was well again, which was the hope at that time. Chris didn’t want us to stop but there was a time when we had to think that through.

It still must have been a difficult decision to make. Carrying on without him, there wasn’t a very broad river for us to cross though, especially since we were so hopeful that Chris was going to come back. So we were halfway there really. We were already thinking that as great as Chris is, and as important as he’s been, we, including Chris, felt that for Yes to lose momentum and not do the things we’d committed to was going to be very negative, even though everyone would’ve understood if we’d have pulled out of those gigs.

How’s Billy Sherwood fitting in?

There aren’t too many people who could play those basslines and also sing Chris’ vocal parts. He doesn’t give me or the audience any feeling that he’s trying to emulate Chris. In a strange sort of way he’s always been ready to step in if he needed to. In one way it’s not unlike when Alan White joined in 1972 after we’d finished Close To The Edge and Bill [Bruford] quit. We kind of looked round the room and there was Alan. You couldn’t have asked for a more easy solution to our problems back then. Billy really was ready. He loves bass, he loves singing and he loves Chris.

Heaven & Earth came in for a rough ride from some fans and it had a mixed critical reaction. What are your thoughts on that?

I would totally not argue that with them. For me, that was a hellishly tricky album to make, partly because there was an old fashioned pressure on us: we had to finish it before we moved on to the next thing already on the books that was coming up. It was done in a slightly chaotic way and if people have got criticisms of it, I’ve got no problems with that because I’ve got my own. I’d have preferred another scenario where we didn’t finish it so early, did some touring and came back to it. I’ve found with my solo work that this is the best approach. If I leave it for a little while, when I come back I’ve got fresh ears and I can listen to something anew and say, “That’s never going to work,” or, “Let’s build on that.” You see the strengths and weaknesses of it a lot clearer but you don’t have that chance when you’ve got a tour booked and you’re trying to finish a record. I think there’s a fundamental flaw, not so much in the texturing but the way the songs were taken forward. Sometimes it was kind of hard work not only with the producer [Roy Thomas Baker] but with the band as well on agreeing how we were going to do this or play that. I wouldn’t call Heaven & Earth a record that all the band have the same degree of emotion about in the way that we certainly did when it comes to our earlier records.

How do you respond to the criticism that it lacked the kind of musical ambition that Yes are best known for?

Well, there are the kind of shorter, moodier pieces that we do. Wonderous Stories is nice, lots of short songs can be nice, but somehow there is something more expected from us. Here and there on the album we did arrange stuff up a bit more but something was lost in the mix. I think Subway Walls is good at the end because it does send it off – it’s more like a big ship of Yes.

To what extent do you think the prevalent technology determines these outcomes?

Let me say that the technology is great – I love Pro Tools and I love the way we can work on records and sometimes not even meet! [Laughs] You can basically change anything you like – put the beginning at the end, change the key, anything you want to do. That’s all very well, and this is a major point – we didn’t used to work like that at all. The thoroughbred records we made, The Yes Album, Fragile and Close To The Edge, were all done through a rehearsal period which was arduous and kind of tough but we ploughed on and got some remarkable songs – that’s when you’re collaborating truly. Back then the thing to do was to go in with a version of a song, hear it and change things to make it better.

I don’t kid myself that we could make albums now like we used to, even though it would be ideal. It would take a different mindset and I think that’s where the mindset of most musicians have changed.

It seems as though Yes have always been about people arguing their corners.

There’s a role that people in Yes adopt and we’d all preside over the control room occasionally. I think producers find this kind of intimidating that any one of us can and does suddenly go, “Well, actually, I’m tired of this,” or, “That’s wrong.” We have our say and lots of producers would prefer it if it was just the singer or just the keyboard player. But when it’s five people… [Laughs]

What’s the challenge for you as a person now in your 60s playing parts you created when you were in your 20s?

We’re going to be playing Drama on the UK tour and I actually said to Geoff [Downes], “Do you think we can do it?” [Laughs] Geoff said, “Well, we did then!” We’d already played Machine Messiah and Tempus Fugit considerably in the last five years but the rest of it has not been played since 1980, so it’s really a fascinating challenge. Touch wood, my hands are doing absolutely great and I do look after them – I nurture them and I project that they’re going to be good. They’re not letting me down at all.

How do actually go about the process of relearning an album? Presumably there’s more to it than just sticking on the CD.

Well, I hunt my file of charts for Yes and I came up with some but they were a little bit vague. They weren’t all titled because some of them were written while we were still working on Drama. But here and there I had a little note that said ‘Into The Lens’ and you know what, we’d changed the key by the time we’d finished it [laughs].

Is it important that what you play live on stage sounds just like it does on the album?

You have to do it very much by the book. The book on Drama was written in 1980, so that’s our blueprint. I’m revisiting it, finding out how to do things. I can’t reproduce three guitars at once playing in three-part harmony perhaps like on the original, so how do I do that? Well, simple – I play a chord [laughs]. That means the texture occasionally might not be the same so I’m producing a musical adaptation, if you like.

Fortunately Jon Davison plays a good rhythm guitar. He’ll be playing bits in Machine Messiah and Run To The Light and there may be other times when his work can add something to a piece. The nice thing about Jon is that he can see opportunities to sing it better, last a bit longer and expound a bit more here and there in his vocals.

How often do you practise? Is it several hours a day or is it a more relaxed regime?

What I do every day is I improvise. I sit down and play. Playing a guitar is fundamentally listening to a chord or picking something, seeing if this line is nice and off the top of my head playing. That’s how I’ve written as well over the years – if I think something’s nice or has the germ of an idea, I record it.

My practising involves improvising and writing more than it does scales. Scales are quite tedious to play, although they can help you warm up, but I don’t often use them. There are a couple I like, minor to major chromatically, key by key up the guitar. That’s enough for me. Sometimes after a tour I won’t play for five or six days. That means when I do pick up the guitar, I’m hungry.

You’ve been playing guitar since you were 12 years old, but readers might be surprised to discover you didn’t read music. Is that right?

Yes, I don’t read music. For me, taking up music was a rebellion against order. I suppose order then was maybe school and my dad. What happened was that since it was a rebellion against things, I didn’t really like order in my guitar learning. I got a guitar instruction manual and never got past page one. I didn’t understand what they meant so everything they said after that was meaningless. So I had to learn by just grappling with it. I realised I was never going to be the most studious guitarist.

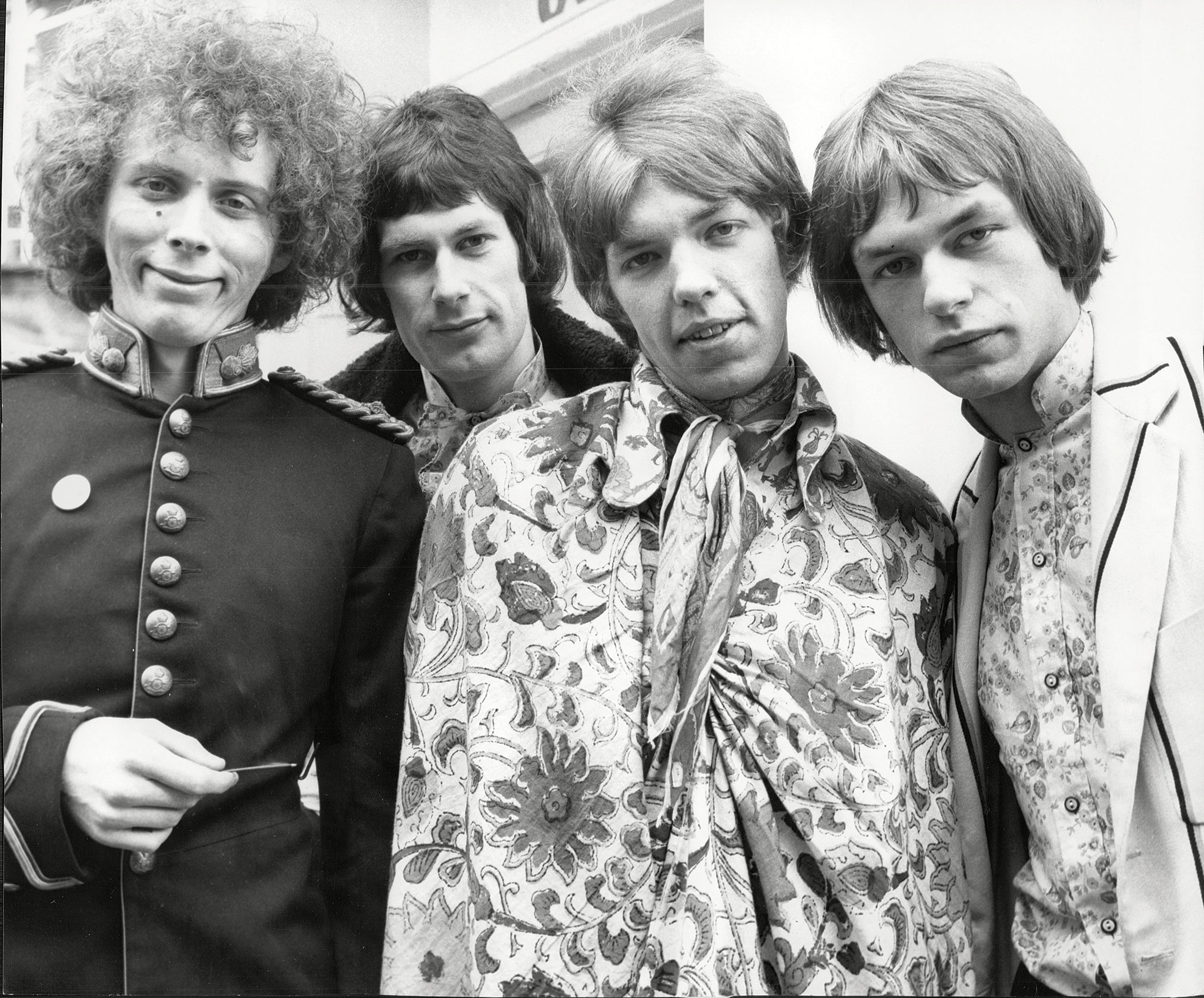

You had an amazing degree of self-confidence as a 20-year-old, working with Tomorrow and a bit later turning down job offers with some pretty serious bands.

I was having a great time. I did join Keith Emerson in The Nice for one day. It was the most beautiful thing. We both liked Vivaldi and we talked about playing some of that but something happened overnight. Not only was I put under pressure by the band I was in, Bodast, about their lives being ruined and them being out on the street if I’d left, but also I’d met some of the people around The Nice and I wasn’t too comfortable with them. So that was it.

What happened with Tull was that they made a precondition. They said, “We’re looking for a guitarist but we don’t want any songs from them.” So that was as far as it got. I didn’t even go to the audition. I spent an afternoon with Atomic Rooster but it didn’t quite gel. Carl Palmer was on drums, although I don’t think he remembers it. I’d even done a stint on tour with PP Arnold when she went out on the Delaney & Bonnie tour with Eric Clapton in 1969. So I’d had these close encounters with other bands which meant I was pretty hungry by the time the call from Yes came.

Where do you think Tales From Topographic Oceans sits in the Yes catalogue?

If there’s five or six top Yes albums then it’s definitely in the midst of those. You have to account for Tales… in our history to properly talk about what we’ve achieved because it was quite exceptional. I don’t think we’d be the same without Tales…

Was it a disappointment for you when Rick Wakeman never really got behind the album?

At the time it didn’t help us but it didn’t really matter because we couldn’t control it. A lot of Rick’s friends were in the press and they were all saying to him that the album was really dodgy. I think Rick wanted to see cracks in it and we didn’t.

We had to learn about Rick going and coming back again. He left but then rejoined on Going For The One. We realised to a certain extent, and it’s not altogether a bad thing, that we were a kind of convenience for Rick. He could always go off and have his solo career, come back to Yes and nip back to being solo again.

Any thoughts on the Anderson Rabin Wakeman project that’s finally been announced?

Maybe there’s three things I can say about it. First, anybody can go out and play Yes music because our music can be explored in so many different ways. The second thing is obviously you’ve got to go out there like Yes have for the last eight years – we’ve proved that we can do things like the full albums show. The third thing is that getting back with people you’ve worked with before is really good, especially if they’re a musician – some of the people we’ve worked with in other fields have certainly derided the band at times and sometimes been quite greedy. That’s the only thing I’ll say.

What do you think about Steven Wilson’s latest remixes of the Yes back catalogue?

My ears and heart tell me that when I hear the original mix, that’s the one for me because that’s the one we sat down and did, but I take my hat off to Steven completely. I give the mixes he’s done 100 per cent support because it’s taking Yes further and further into the future by having these 5.1 and new stereo mixes available. They asked what I thought and if I had any suggestions or questions. I went down to see Steven at his studio, which has a huge screen with the album on it in Pro Tools and everything, and we analysed some of the music and I was able to help with a couple of things he was working on at the time.

If push comes to shove, what would be the Desert Island Yes album for you?

I’ve got to shoot for something as solid as Close To The Edge really. That record to me will never lose its intrigue and glamour, if you like. That was a pretty high achiever in my opinion.

How would you describe Yes’ contribution to the explosion of progressive music in the 60s and 70s?

We were just five crazy guys who had some chemistry, and if you can add that to the songs and the sound, with good production, then we do rank as one of the bands who did all that. And the quite surprising thing is that we’re still going, even if certain periods were quite different from others, and not least of all Heaven & Earth. When it comes to the story of Yes, you certainly get a mixed bag.