The quiet life and sober times of Peter Frederick Way

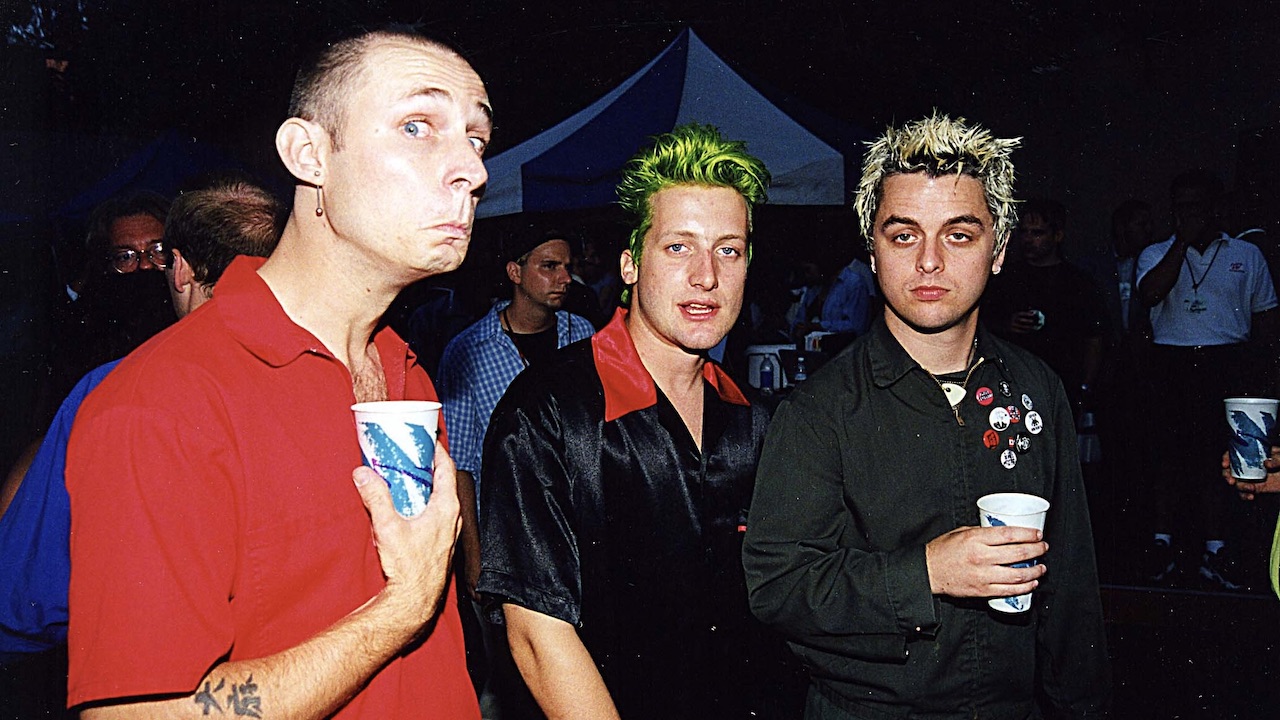

In 2013 former UFO bassist Pete Way sat down with Classic Rock to discuss his extraordinary life... and four decades of hellraising

Before we start, let’s get one thing straight: Pete Way is off the drugs – he’s off the coke, off the smack and off the booze. Well, more or less off the booze, he adds. Except for the odd night, when he might have a glass of wine. Or maybe two.

“But that’s okay,” he says, sounding suspiciously like a man trying to convince himself as much as anyone else. “No, really, it is. I can handle that. It’s fine.”

Put that down as well, he says: off the booze. He clasps his hands together and puffs out his chest. He looks proud, pleased with himself, like he’s done something he never thought he would. He’s clean. Well, clean-ish.

This is a strange new feeling for the self-proclaimed king of the junkies, a man whose forearms were so scarred by needle marks that he had them surgically repaired, a man whose leg veins were so damaged from injecting smack that they leaked blood into his feet. Those veins have now been removed. Somehow, he still walks.

“When I think of what I’ve done – the drugs, the drink, the damage I’ve caused to my body – I feel blessed. I shouldn’t be here,” he says. “Someone up there, I don’t know who, but someone up there is looking after me.”

We go through a roll-call of vintage rock stars with chequered pasts, some dead, some alive, big names with unhealthy appetites for destruction. He doesn’t think any of them could match him. He’s not bragging, it’s just the way it is.

When the bassist left UFO in 1982 – supposedly because he didn’t like the band’s more commercial material, because he was fed up with touring, but also because his drug intake was beginning to escalate – he joined Ozzy Osbourne’s band. It was like Eric Pickles getting a job at Greggs the bakers. It didn’t last long.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Ozzy used to say I was a bad influence on him. I was the biggest junkie of them all.”

He laughs, a thin, rasping laugh, which soon fades. He’s cracked these jokes and lived this life for the best part of 40 years. Pete Way, the party animal: first at the bar, last one to bed. A life of brilliant music and sold-out shows, all fuelled by a never-ending line of cocaine and heroin. It’s been one long wheeze.

Way didn’t just live it, he loved it: the rock, the roll, the good times, the excess. Now, though, it’s different. Those days are over. If he wants to live – with his veinless legs, his damaged liver, his lasered forearms, a body that has been battered and abused for four decades – things have got to change. Pete Way is getting sober.

So what’s Pete Way like? If I had a pound for every time someone had asked me that question, I’d have enough for a UFO-styled night out. If you really want to know, then read on – his words can tell you more than mine can. But if you want the not-so-scientific synopsis, then I’d say he was decent: an easygoing, laid-back bloke. I wanted to like him because I grew up liking him. And I did. I liked him a lot. It was a relief.

Unfortunately, it’s not always like that with rock stars you grew up admiring. If you’re asking me how he’s looking, though, or how he’s coping, then, truthfully, I’m not quite so sure. Pete Way is 62. And although he can still get away with tight tops and 30-inch-waist jeans, and his hair is still semi-long and black, he’s beginning to look his age. It’s not surprising. Forty years of excess have taken their toll.

I’m here to talk to him about his new album and his old life, machine-gunning him with all sorts of obvious and impertinent questions he’s no doubt been asked a thousand times before. To his credit, he doesn’t dodge one of them, even the really grim ones. He winces a couple of times and pulls a face now and then, but he still answers them. He doesn’t have to. He could tell me to fuck off. But he doesn’t. In a business full of bullshitters and egotists, Pete Way is all right.

It’s only when he lays it all out, this life less ordinary, that you see all the dark shadows that loom over the magazine covers and platinum records. The story Pete Way is telling today is the story Pete Way has never told before. What you have here is the abridged version. If he’s got any sense, he’ll turn it into a book. Because amid all the rock and all the roll, it’s a hell of a story.

Five broken marriages. Two deceased wives, both of them victims of a lifestyle that Pete somehow survived. Millions of pounds squandered in bad deals and divorces. Millions more snorted and injected. Numerous failed attempts at rehab. Two daughters he barely knows, grandchildren he’s never met. A new-found sobriety that he treasures but is worryingly fragile. It’s all here.

Later in the interview, he tries to find out the Aston Villa result. How did this north London boy end up draped in the claret and blue of the West Midlands football team? Was it a doting father or some other influential family figure?

“Nah, it’s from drinking round here in Birmingham.”

When UFO were off the road in the 80s and 90s and Way was living in Birmingham, he would spend his days in the pub. The all-day drinkers would ask him: “Who do you support, son?” He realised hedidn’t support anyone. “I said: ‘I support Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple.’ But they wouldn’t have that, so they introduced me to the Villa. And that was that.”

Today Villa are playing at home to West Ham. If they’ve lost, he declares, he’s “going off on one”. Is he joking? Possibly. He’s cracking jokes and laughing all the time. Maybe this is just another gag. Let’s hope it is. Maybe he means he’ll just have one, or two, and, just like he says, it will be all right.

“I take it day by day,“ he says later. “I’m always on the brink. It’s never far away, you know.” He smiles. A front tooth is missing. The trouble with the drugs wasn’t how they affected him, he says, it was how they affected those around him.

“I could handle it. I never really had a problem with drugs. I could handle the coke. I never really had a problem with the booze, alcohol was always just a social thing.”

It only really became a problem when he graduated to heroin, and only then after he’d been a fully functioning heroin addict for the best part of 10 years. And only then, really, because he found his wife dead, curled up and blue on his bathroom floor. When you see something like that, he’ll tell you, it tends to straighten you up pretty fast.

“What you have to remember with the drugs and the booze is that it all started very gradually, very innocently. I didn’t start off as a heroin addict. I used to drink shandy when I was first in UFO.

“Then Phil [Mogg, vocals] bought me a beer. I liked that, so I had more beer. And then one day you’re touching down in Los Angeles, 23 years old, the world at your feet, and someone says: ‘Hey, do you want a line of coke?’ And everyone is doing it – I mean everyone. So you have a line of coke and… Oh, hell-oooo… That’s all right… And you’re off.”

Success happened fast for the young man from north London. His first band, The Boyfriends – “Sounds a bit gay now, that, doesn’t it?” he says – was disastrous, but he fell in with Mogg and guitarist Mick Bolton and formed UFO. Before Michael Schenker entered their orbit in 1973, UFO were a plodding space-rock band who had a couple of unlikely hits with Boogie For George and a cover of Eddie Cochran’s C’Mon Everybody.

The UFO ship only really started to take off after they got a boost when their guitar player, Bernie Marsden (later of Whitesnake) missed a flight to Germany and, out of necessity, the band had to play a show with the hastily borrowed guitar player from their support act, Scorpions. Step forward 18-year-old Michael Schenker, soon to be permanent member of UFO.

With Schenker on board, a new era for UFO began. For the next five years and five studio albums – Phenomenon (1974), Force It (’75), No Heavy Petting (’76), Lights Out (’77), Obsession (’78) – the band were untouchable.

Schenker spoke virtually no English and the band spoke no German, but “the music was so good it didn’t matter about that,” says Way. “It was instinctive. We just used to nod at each other and we knew where we were. We played and played and played until we became good.” But more than anything else, he says, “it was fun. Just great fun.”

I don’t think I was sober for long enough to get a hangover

Pete Way

As the albums got better, the gigs got bigger and the tours got longer. In the States, UFO went from 3,000-people concert halls to 18,000-capacity arenas in the space of two albums and two years. “We didn’t worry about a thing,” Way says. “We were driven everywhere in limos. We stayed at the best hotels. We flew first class.”

And as the shows got bigger, so did the excess. “On tour, we used to write the drugs off as medical expenses. No one questioned that, until one month when we tried to claim $28,000 in medical expenses. That’s when someone said: ‘Hang on, what’s all this?’

“I remember one night a guy turned up with a suitcase full of coke. We didn’t think: ‘Right, we’ll have a bit of that now, save some for tomorrow and the rest of the week,’ we just had it all.

“But we did it because we felt we deserved it. We made records that I was proud of, but what I’m most proud of are the shows we did.”

UFO made millions. But they should have made millions more. “The accounts for UFO were all written in pencil. They were a work of art. I know, I saw them,” he recalls. “I could sit here and get cross about it, sure, but what’s the point? It’s gone, innit? I don’t want to feel bitter for what could have been, I want to feel grateful for what I had.”

Wherever they went, there were drugs, booze, fast cars, faster women, all the clichés you can think of. But Way will tell you that what mattered most was the music – it was all about the show that night.

“We wouldn’t get wasted before a gig. We’d perhaps have a couple, but we’d play the show pretty straight. We were always serious about that. We didn’t make many mistakes. We were so well drilled. Strangers In The Night, the live album, is pretty much as it was. I think we might have tinkered with the crowd noise, but it’s not overdubbed like a lot of those live albums were. There was no need. We were a fucking good live band.

“We had this agreement that if anyone made a mistake, we wouldn’t go at it there and then, we’d discuss it the next day.” After each show, they’d get stuck into their rider. And there’d be a party somewhere. And someone would chop out a line, then another… “And before you know it, the mistakes were forgotten. We never rowed about that. We just floated along.”

When tensions did arise, the even-tempered Way found himself in the middle of it all. “It was Michael and Phil, really. I was like a rock’n’roll Henry Kissinger, trying to bring peace, calm it all down.”

But it didn’t work. An agitated Schenker left UFO in October 1978. “Joe Perry told me years later that Michael spent a week auditioning for Aerosmith,“ says Way. In his place, UFO brought in Paul Chapman – nicknamed ‘Tonka’ because he was indestructible, despite his voracious after-show appetite – from Lone Star. Unsurprisingly, he slotted into UFO a treat. The UFO bandwagon rolled on.

When Pete is asked whether he was starting to feel the effects of this playing, touring and ‘rock’n’roll lifestyle’, he shakes his head. “I never got a hangover,” he says. “I don’t think I was sober for long enough to get a hangover. I didn’t stop. I’d sleep in the afternoon, perhaps, on the way to the show. I’d get an hour or two. Then I’d just top it up again. I didn’t see it as self-destruction, I saw it as a lifestyle. My job. It was what I did. I was good at it, too. It was just being in a rock’n’roll band.”

Did you ever have a night off?

“We had night offs when we didn’t play, yeah.”

No, I mean a night off from the drinking and the drugs.

“No, I don’t think we did. We all knew that we all had a certain level, a limit.”

What was your limit?

“I don’t think I ever found my limit. I seemed to be constantly just under it. David Coverdale said to me once: ’Everything in moderation, dear boy.’ My trouble was, I didn’t do moderation.

“I do remember one night, I fell asleep on stage. I must have been up for three days, and we used to take a Mandrax, a sedative, right before the last encore to just help us to chill out. We used to time these things to perfection. But this one kicked in a bit early, and I fell asleep halfway through Shoot Shoot. They had to carry me off.“

The Five Wives Of Peter Frederick Way. If that sounds like a kind of grim, Roddy Doyle-type novel full of death and booze and infidelity and expensive divorces, that’s because it’s precisely what it is.

Pete runs through them one by one. “Forgive me,” he says, “I’m a bit hazy on the dates.”

Wife number one was Yvonne. They met before the big time arrived. When it did, and when Pete tasted it and decided he liked it, their union was doomed. “I worked with her at the Customs office, where I used to work in London. I was spending more time going from there to record offices in the city with band demos.

“I met Yvonne, we got married, and we had Zowie [his daughter]. And then the band happened, and she was on her own all the time and I was away, playing in France or Japan. That was the beginning of the end. I was discovering this other life, and it left Yvonne behind a bit.”

The marriage ended. Pete lost his first house and a sizeable sum in alimony. More than that, he lost his daughter. They’re only now beginning to repair that relationship.

Wife number two: Josephine.

Ah,” he says. “That was down to me having a relationship with her sister-in-law and her sister-in-law’s mate while she was away. I regretted that. It wasn’t her fault. She didn’t deserve that.” [After this feature originally went to press, Classic Rock established that Way's affair had actually been with Josephine's sister. We published a correction].

They were together for five years, he thinks, maybe more. They had a daughter, Charlotte. “I was never there,” he admits. “I was always on tour. We toured constantly for three years. I think I had a week off every three months and I’d go back to my house in LA and Josephine.”

Apart from the time when he went to Boston and met her sister, and word got back and, understandably, “that didn’t go down too well”. Another marriage gone. And with it another house, another big settlement, another girl who grew up without knowing her dad. [Josephine subsequently told Classic Rock that although she continued to live in the same house she shared with Pete Way, she was not "given it" as part any divorce settlement – in fact there was no settlement – and had been paying the mortgage ever since].

All the time, the UFO spaceship surged onwards.

Then along came Bethina, wife number three. Bethina was Danish. A model. “I met her in London. We were friends first. We partied together. She shared my appetite for drugs.”

The marriage went the same way as the previous two – washed up on the rocks of his career and his debauchery. Pete carried on. Bethina found it more difficult. They found her a few years ago. Her body had given up, worn out by a lifestyle Pete survived.

“I don’t know what happened,” he says. “We’d separated. I gave her money, I looked after her. I don’t know. I just don’t know. They told me that she just couldn’t take it any more. Her body just stopped.”

Wife number four was Joanna, an American doctor. “Which was handy for me, ’cos I used to nick all sorts of stuff from her – and she was good with needles,” he says. He met her after a show in the US. Brian Wheat from Tesla introduced them, and they hit it off immediately.

“It was the 90s, the band was working on and off, and I was living in this big mansion in Ohio.” It looked grand from the outside: this 170-year-old, eight-bedroomed house in a nice area of Columbus, the state’s capital. It wasn’t quite so lavish inside. Pete and Joanna were getting into heroin.

“We lived in one room. We were seriously getting into the gear around this time. Before then it was mainly coke and booze, heroin occasionally. Then it got more serious. We’d sit there, in one room, injecting and watching TV. I had these two fast sports cars just sitting in the garage and I never drove them. By then I wasn’t using heroin to get high, I was using it not to get ill.”

There was a brief UFO tour. Trouble with a visa caused Pete to be late getting home. Then he missed a flight, which made him later. It was a typical UFO-style shambles.

“I got back to the house and I had to break in. I didn’t know where she was. I shouted for her. There was no response.”

He found Joanna’s body on the bathroom floor. She was cold. Her flesh was blue. She’d been dead for two days, the coroner said afterwards. “I knew she was dead, but I leaned over her and gave her the kiss of life,” he says. She didn’t move. Her lips were cold.

Way has forgotten all manner of things in a life that has been deluged with copious amounts of illicit substances. But he hasn’t forgotten that. He wishes he could. “You can’t forget things like that.” He stopped taking heroin shortly after.

His fifth wife was Rashida, also an American.

“We’re just going through a divorce now. The less said about her the better.”

It’s difficult to say how much it’s all cost him in alimony and divorce settlements, houses and bills. Eight million? Three million? Ten million? He doesn’t know. He doesn’t keep a particularly close eye on the money. He never has. “A lot,” he offers. “I try not to think about it. It’s only money, though.”

It’s a Sunday afternoon in Birmingham. We’re at a rehearsal studio not quite on the wrong side of town but close enough for everyone on the street to be wearing a hood – and not just because it’s raining.

“I wouldn’t leave your car out there, mate,” a friendly Brummie advises, as we stand shoulder to shoulder having a piss in the studio’s urinals. “You might come out and find it’s on bricks.” Like Pete, I think he’s joking but I’m not sure.

Pete’s here to put the finishing touches to his album, a batch of 14 new songs that have been three years in the making. The new record – with Pete on part-time bass and raspy vocals – will be called Walking On The Edge. He doesn’t need to explain why; the title makes perfect sense. It’s a musical biography.

He arrives late. People like Pete Way are pathologically late. He’s driven up from the south coast this morning in terrible weather with his publicist, Jenny.

“Pete had to stop for a pee at every service station on the way here,” she says. She’s only half-joking. During our three-hour interview, he’s constantly up and down the stairs to the toilets – he thinks he might have eaten something a bit dodgy.

He’s weighing in at 10-and-a-half stone these days. “My fighting weight.” During the heroin years he weighed less than nine.

He goes to the gym now, Jenny says. He eats well.He runs, too. Pete Way – jogging. You wonder how he does that, with legs that have barely any veins, but somehow he does. He’s trying, she says. He’s really trying. He’s tried before, of course. He’s tried numerous times.

The last time he was in rehab, his mates turned up with a small packet of Peruvian cocaine. The self-proclaimed king of the junkies half-heartedly scolded them, but before he’d finished with the finger-wagging, the coke was up his nose. Another short-lived shot at sobriety. Back in the saddle. Again.

This time, though, he’s doing it because he wants to, not because everyone else is insisting he should. And it makes all the difference, he says.

I don’t want to feel bitter for what could have been, I want to feel grateful for what I had

Pete Way

And then there’s the album. He doesn’t have to record another album. The royalty cheques that arrive every three or four months afford him the luxury of never having to work again if he chooses. He does it because he wants to. “Besides, what else am I going to do?

“Come and have a listen to the album. No one has heard it yet.” As a journalist, few things can be more excruciating than being taken into a room with a musician – all wide-eyed and eager – and forced to listen to their new album, as they sit by your side, nudging you, explaining “this bit” and “that bit”.

Walking On The Edge will be released some time this spring. We’re listening to the unmixed version. It will be mixed by Mike Clink, famed Guns N’ Roses producer and long-time friend of Pete’s, in the next few weeks. A young Mike Clink was the engineer to UFO producer Ron Nevison. In 1986, it was this tenuous connection to UFO that persuaded GN’R to hire Clink as their producer. You know what happened next. He went on to produce the next four GN’R albums (five, counting GN’R Lies), which sold around 90 million. Today Mike Clink is a millionaire.

Would he like to produce Pete Way’s new album? Sure, he says. If it’s for Pete, why not?

Jason Poole is the name of Pete’s guitar player. “I wrote most of the songs,” says Pete, “then I gave them to Jason and he helped to jazz them up a bit.” It turns out that Jason also played bass on some of the tracks. I wonder how that worked, having Pete in the band and someone else playing bass. Isn’t that like having Lionel Messi in your team and leaving him on the bench? No, says Pete. It’s fine. Jason is a good guitar player. He’s handled it all brilliantly.

Jason presses play. We’re off. He plays four songs – Narcotic, The First Shot, Forever and Love, Needles And Sympathy. There’s a story behind each one.

Narcotic is the real-life account of a man in rehab who is visited by friends who have smuggled in some cocaine. You can guess who that’s about. Pete seems especially excited by this one. I can’t really be sure what it’s like because Pete was talking to me, telling me what each bit meant, all the way through it.

The First Shot comes on like a spaghetti-western soundtrack, all leather chaps and malevolence, a lone gunman walking through swinging doors, whistling, looking for trouble and finding it. ‘The first shot is the sweetest’, goes the chorus. “I’ve tried not to make them all drug-related,” says Pete. You’d never know. It’s a memorable song full of big hooks.

Forever is the big, sweeping ballad, sung by a woman with the sweetest, clearest voice. Except it’s not a woman. “That’s Dr B, my clinician. He works at Queens in Birmingham. He sang it in one take.”

Love, Needles And Sympathy is also autobiographical. “I was a skinhead, you know, as a kid, until I met Phil and he told me not to be,” he says. If it wasn’t for the Thin Lizzy sensibilities, this would be the closest thing to a UFO song on the album.

Guest drummers include former UFO man Clive Edwards and ex-Scorpions rhythm man, Herman Rarebell. It was recorded “Here, there and everywhere,” says Pete. “There’s real variety on here. There are rockers, ballads, a song that sounds like Johnny Cash. I think it’s going to be good. When it’s out, I’ll tour it. I’ll tour it everywhere.”

All in all, it’s fine, great in parts, certainly better than anyone could have realistically expected. Does it sound like Love To Love? No, it doesn’t. But, you know, what does? I’m sure it will sound better when Mike Clink has worked his magic, too. I hope it does well.

We go back upstairs to the bar and drink coffee. Pete goes to the toilet. He’s just played me his new album, and he’s excited about it and he has every right to be. And yet I know I need to get round to The Impertinent Question That Needs To Be Asked: when is he going to rejoin his old band?

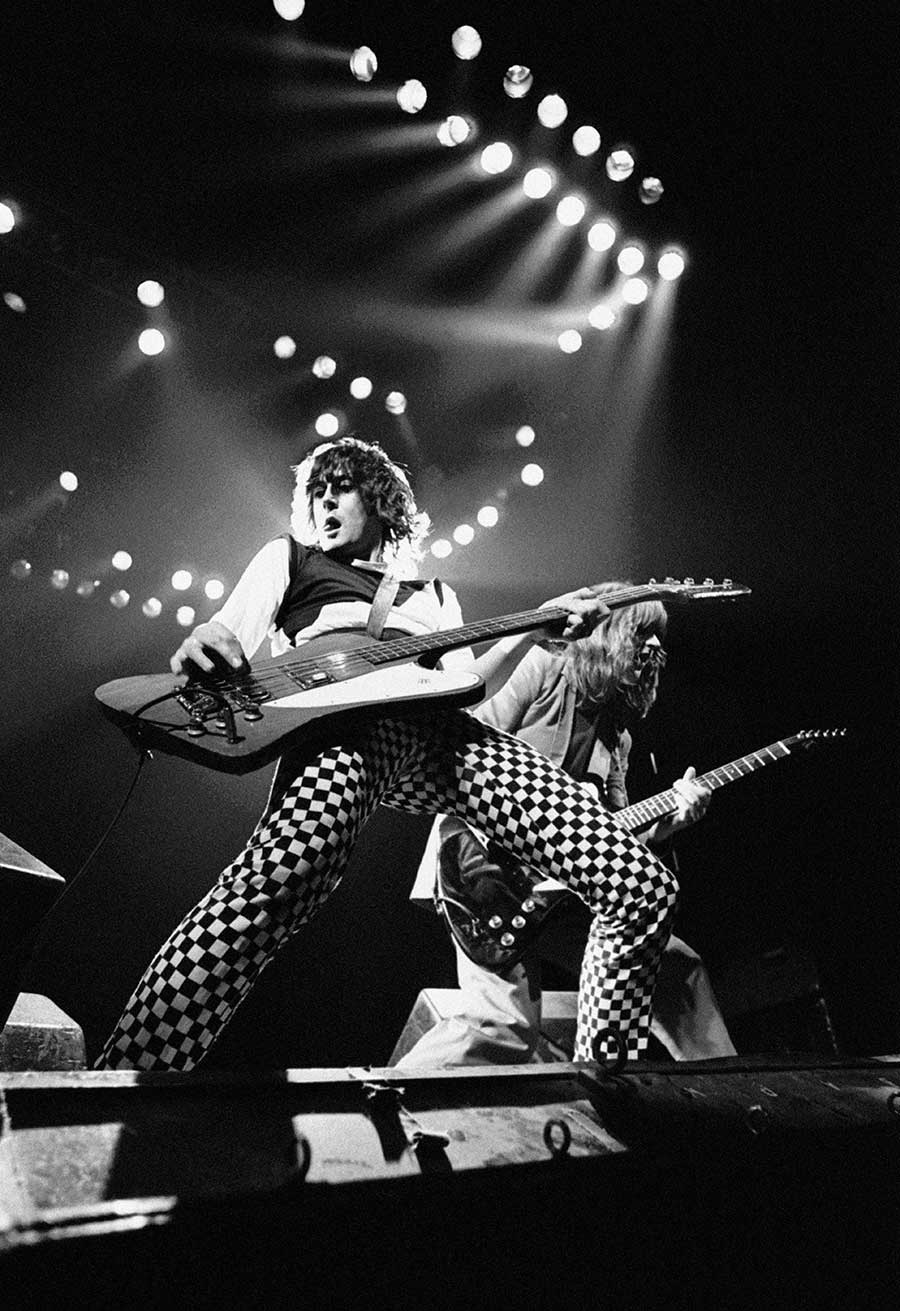

UFO without Pete Way. It’s not right, is it? One of the finest British rock bands of the past 40 years without their show-stealing, shape-throwing, stripey-spandex-wearing bass player.

So, why are you not with them? They’re your band. They miss you. We miss you. You should sort it out shouldn’t you? “Yeah but… I don’t know… It’s not a priority for me at the minute,” he says. “I don’t have a burning desire to do it. Have I been asked? Yes, I’ve been asked but I wasn’t in a place to be able to do it when I was asked. I wish them all the best, I do, honestly.

“I think they’ve had some great bass players in UFO. I’ve liked all of them. Most of them have been my mates. I’m still friends with Phil and Andy [Parker]. I speak to them a lot. There’s no animosity there at all. The only person that surprises me is Paul Raymond. He’s said a few things that I thought we’re unnecessary, a few digs. Shame, really.”

These days, he plays mainly with a pick: “I can still play with my fingers, but it’s easier with a pick.” There was a time, he says, when he would wake up in the morning, from another smack-induced stupor, and he’d have to prise his hand open, pull his fingers out, one by one. It was grim, he says. His right hand – a hand that has influenced all sorts of bass players, including, most notably, Iron Maiden’s Steve Harris – looks swollen. “It’s fine,” he says. “I can still play.”

His liver, his poor abused liver, is less fine. It’s also swollen, enlarged by hepatitis. Of all the substances – alcohol, coke, speed, heroin – the booze remains the hardest one to kick.

“It’s just a social thing isn’t it? You can’t hide from it. It’s everywhere.”

So how will he cope when he’s on tour – playing all these bars, surrounded by people drinking?

“I think it will be okay,“ he says. “I can handle that. You have to put on a show. You can’t do that if you’re out of it. You just left yourself down.”

Has he fallen off the wagon? He looks sheepish. Occasionally, he says.

His mum died just after Christmas. That was tough, he says, not just her death, but her final days. It was hard to witness that.

“I’ve put behind me the things that can destroy me. I had a choice. Did I want to live – or did I want to die? And I wanted to live. There are still things I want to do. I don’t know what’s round the corner. All I know is this – I’ve missed making music. It’s what I do. So I’m glad to be back.

“And I know this – whatever happens now, I’m not going to make a fool out of myself.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 184, in June 2013.