It’s a rare day of sunshine in the Welsh countryside. Since the band had arrived it had been slabs of grey skies and low clouds over the green hills.

Seen from above, the residential Rockfield Studios in Monmouthshire is a block of buildings – the old stables, filled with glass sheets, act as a real echo chamber – set as a quadrangle around the main courtyard.

Spotting a rare interlude in among the constant drizzle, drummer Neil Peart is quickly out on the cobbles, toying with some percussion blocks, their repercussive zing bouncing sharply off the surrounding bricks.

Somewhere above the collective heads of Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and producer Terry Brown, a light bulb sparks into life.

Brown brings a stereo mic out to the centre of the courtyard and wires it up as Lifeson looks on, strumming his acoustic guitar. It’s quiet, birds chirrup, and in the distance, a nonplussed herd of sheep stand at the fence. “Those knocking sounds at the beginning of Xanadu,” says Lee, rapping on the oak table between us for effect, “that’s the sound of the courtyard, the natural sound of that square. We got such a nice reflection off the buildings, we knew we could use them in some way.

“The guitar at the start of A Farewell To Kings, the title song, was recorded outside too. The acoustic was recorded out there to get that really crisp sound and I remember Alex was walking around this mic that Terry had set up while he was playing. He was just like a troubadour – he was playing as he walked around and, naturally, every troubadour has his guy trailing behind him playing a Minimoog!

“So I’m playing the Minimoog outside and Neil’s hitting the twinklies or whatever he was hitting off the front of that – he was always hitting something – and Alex is walking around this mic recording the opening to A Farewell To Kings, so it was quite fun. You can hear the Welsh birds singing in the background, unless they flew in from somewhere else – they could be accidentals, as they’re called in the trade.

“Farewell… was quite a different piece for us, because of the way the intro’s structured, and then it comes in with a bang and there’s this weird time signature going on. It’s a tough song to play.”

“We set up on the cobblestone courtyard with a pair of mics and created our own stereo spread,” says Lifeson. “I do recall walking back and forth, trying to concentrate on my playing while not crashing into Neil. It was a complex song to write. In many ways, it’s simple and direct, but we could never accept that, so dropping a note here or inserting a weird note there made things more interesting for us and for the listener. Odd time signatures were a great way to keep the listeners scratching their heads and counting on all fingers.

“I liked the organic nature of that recording and it was one of the few days that it didn’t rain… though I think it did start again later.”

It had been a tumultuous ride up to A Farewell To Kings. Rush were following the acclaimed 2112 album, which they had released after the poorly received Caress Of Steel and the threat of being dropped by their label. The success of 2112 had given them their creative freedom, and the quickly assembled live album All The World’s A Stage was their stopgap. Lee reveals: “…Stage was definitely something we used to buy us more time.”

Though …Kings was to be their fifth studio album, the band members were still barely in their mid-20s.

So how do you follow a concept album about a dystopian future where music is banned, civilisation is domineered by a hierarchy of priests and the lead protagonist commits suicide in order to free society? Good question. For Rush, you create a record informed by socialist polemic, the movies Mr Deeds Goes To Town and Citizen Kane, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poetry, a nod to Don Quixote and what passed for a fiery death in the heart of a black hole. And in Madrigal, they even wrote a love song, albeit one that referenced dragons. It was a Rush album, after all.

It was springtime in Toronto and Rush were wondering what to do next. The band were toying with going back into work at Terry Brown’s Toronto Sound Studios (where they’d recorded their four previous albums), but as the band’s success escalated, so did demands on their time.

“We were doing well in Canada,” says Lee, “and things were getting more hectic. Frankly, we wanted to go somewhere where there were less distractions. Rockfield was our first residential record – we’d never done that sort of thing before – so Terry suggested: why don’t we look for a place where we could stay and work. We were all up for the adventure.”

For his part, Lifeson is a little more circumspect: “Did I mention the rain? I mean, all the time. That said, it was exciting to be in another country for an extended period and focus on making the record. I don’t think we took any days off, but we never really wanted to. Living together, working together, it’s what you dream of when you’re young and starting out with a band. It was so much fun.”

“You have to remember, we were these dazzling urbanites at the time!” says Lee, laughing so hard he almost spills his glass of Riesling. “And here we are on the farm in Wales. It was… how do I put this? It was quite different. I remember when we first arrived, we had a bunch of our crew guys helping us load in, and one of the guys who worked for us at the time, his nickname was Lurch – he was 6’11.

“The weather was warm, wet but warm, but road crew tends to wear shorts whether it’s warm or not. Anyway, some of our guys went to town with Lurch and you know, maybe it’s changed, but back then you didn’t see a lot of men wearing short pants, just children usually. Grown-ups didn’t wear short pants a lot. So they’re walking down the street with this guy who was a tough-looking character, is nearly seven feet tall and wearing short pants, and every time they passed someone, people would turn and giggle and laugh and point.

“So it was a bit of a culture shock for us. It was June, but you’d never know it was summer – it was Wales. I think we had three sunny days the entire time. It was perpetually grey, and the schedule started fairly normally: we’d start at midday and then we’d work, we’d take our meals together and they cooked for you and that was our first experience of anything like that… it was an adjustment.

“After about three weeks, we were working later and later into the night and sleeping later and later until eventually we got our schedule completely back to front, where we were having breakfast at supper time and working all night long and crashing after the ‘baa, baa’ [he offers a full-throated and pretty convincing impression of a sheep] was happening in the morning. The birds and the baas! That was bedtime for us. That’s why you hear so many birds when we recorded outside. I’m amazed there aren’t any sheep on the album.”

Lifeson adds: “It was quiet at Rockfield, to be sure – very conducive for working, except for the constant bleating of sheep…”

![Double Vision: Alex Lifeson [left] onstage with the famous double-necked guitar](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/zH7FLFQBM9a2XoRbAw9PX.jpg)

As a band that averaged around 250 shows a year, Rush, as was the case with their three previous albums, had very little material worked up before they went into the studio. Lee says: “You get 10 years to write your first album, 10 days to make every one after that. It’s the same for every band.”

That said, they had road-tested a few of the songs before going into the studio, including one that would become the record’s cornerstone and a live staple for the rest of their careers – and it was recorded in one remarkable take.

“We had played Xanadu before we recorded it,” says Lee dryly. “You know, the easy songs an audience can take in and appreciate without knowing what the hell they are. We certainly had the parts of that and I think Closer To The Heart might have been written. Not much else beside that – the rest of it was done on the spot. It was sort of how we were working back then, because we didn’t have time – you’re on the road all the time, so you have to write as you’re moving.”

“Xanadu was well rehearsed before going to Rockfield, I remember that,” adds Lifeson. “On the day we recorded it, Pat Moran, the resident engineer, set all the mics up and we ran the song down, partially to get balances and tones. Because it was a long song, we didn’t need to complete that test run.

“We then played it a second time from top to bottom and that’s what you hear on the album. Needless to say, Pat was shocked that we ran an 11-minute song down in one complete take. Practice doesn’t always make perfect, but it sure helps!”

Did they realise how magical and inventive Xanadu was?

“Xanadu was too difficult to play to feel magical at the time!” Lifeson says. “But it did feel like we were moving on into another direction and this whole other level of performance.”

“I don’t think we ever think of our music in that way – maybe later,” says Lee. “You have an idea and you have a soundscape you’re trying to create. With Xanadu, I’m not sure people realise this, but even though it’s loosely based on Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, it’s also very influenced by Citizen Kane.

“If you look at the opening of the newsreel of Citizen Kane, they quote that poem: [he adopts the opening tone of the original voiceover] ‘In Xanadu the pleasure dome did decree…’ and that whole sort of animated opening to that, so I kept that in mind when we created the soundscape to the opening of that song. I always had that visual in my brain as we were making the music, I always had a connection to that whole thing. They’re intertwined for me.

“Xanadu was also one of the greatest live songs we’ve ever done, it was tour de force, it was a moment for the lights, it was a moment for the double-neck guitars. It was a big moment! Though not so much for my poor back.”

Those double-necks took on a life of their own: on the R40 tour, there was a sort of happy pandemonium as the band strapped them on.

“Frankly, we’ve never lived those guitars down,” says Lee. “Can’t get past it, mate! And you’re right, when we brought them back on the last tour, people lost their minds – the double-necks, they’re back, alert the media!

“But form follows function, right? We had those double-necks for a reason, because it was always imperative for us to be able to reproduce our records as accurately as we could. And we were doing more overdubs and experimenting with sounds, so we needed more strings on stage, we needed more flexibility. Alex plays a six-string and a 12-string in Xanadu, so he needed that guitar.”

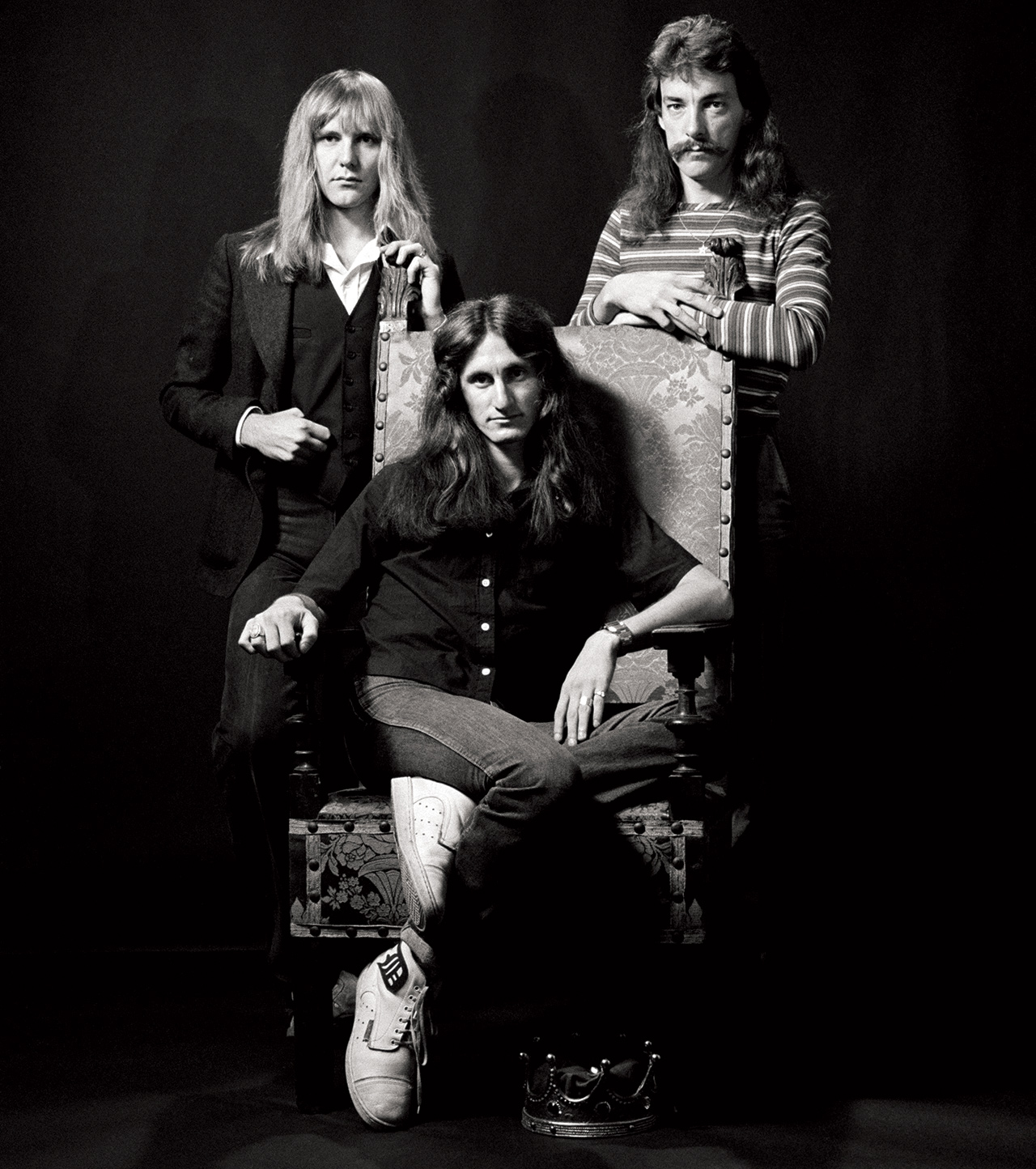

“That’s certainly where it began in earnest,” says Lifeson, “but I’d been incorporating 12-string since the first album, and to have the flexibility to switch between the 12- and six-string opened other doors to our sound and songwriting. It’s funny because we didn’t use them much, yet they became these iconic images for the band. I probably see at least as many double-neck photos of us as regular ones.”

Orson Welles’ iconic Citizen Kane wasn’t the only cinematic note to be introduced into the A Farewell To Kings mix. In terms of songwriting credits, Closer To The Heart was co-written with poet Peter Talbot, while Lee brought in the lyrics for Cinderella Man.

“That was inspired by one of my favourite movies, the original Mr Deeds Goes To Town, where he’s referred to as a Cinderella man. I was a big film guy as a teenager, and as a young man, I was really a film buff – I watched films all the time. I studied directors because I sort of secretly wanted to be a film director. It was just one of those dreams for when I grow up. And when I realised that most directors have to be part megalomaniac, I think I sort of went off that idea. But I loved film, I still do. The old films, my wife and I used to watch them all the time together, and so the Capra movies were big with me – lot of heart, lot of soul, lot of showing the best and worst of America and its people.

“So that song is really just about that movie and the kind of themes that movie resonated with. It was my thing that I brought in and Neil helped me clean it up a bit. One thing in Rush is that we’ve always allowed ourselves to go where we want to go as individuals and see it how flies. We all have to be behind it to use it. But there were no real boundaries in our band.”

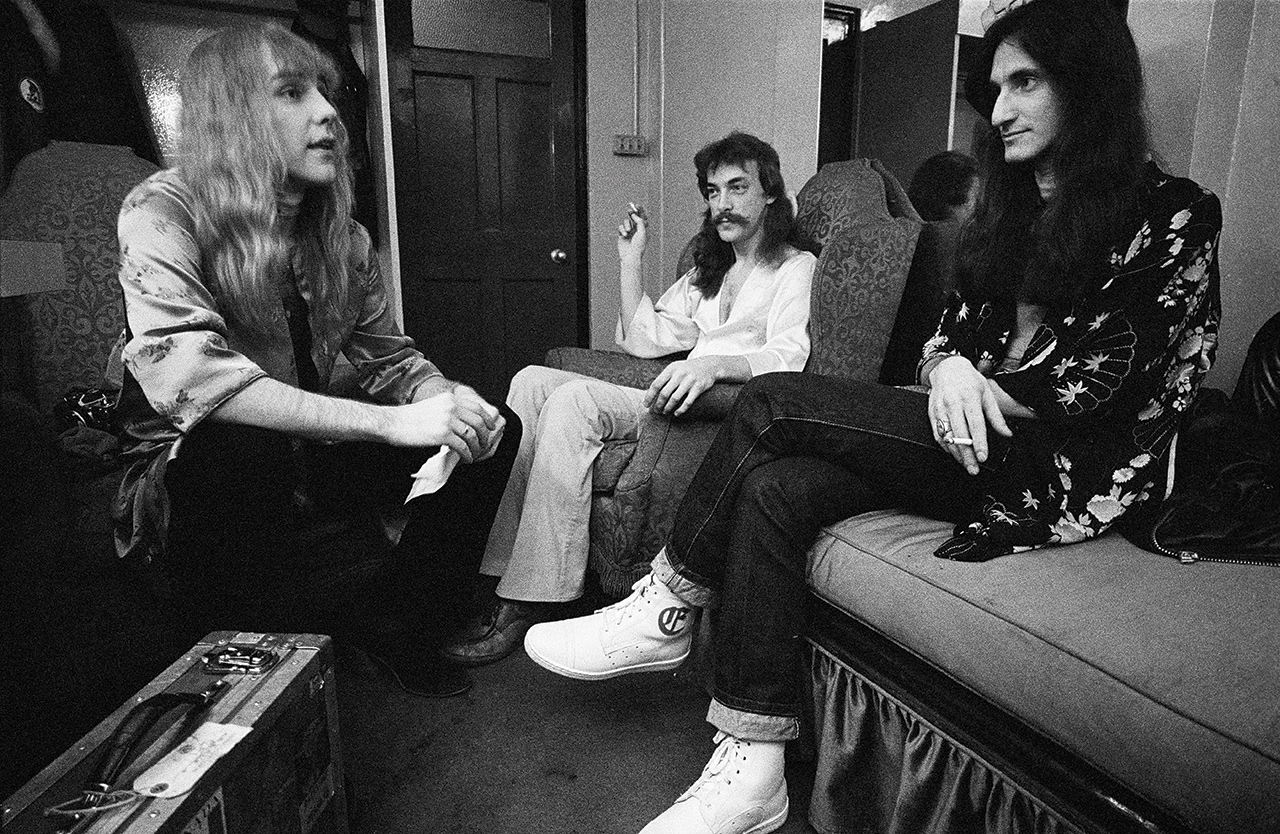

Much later, the band would record their albums in shifts, Lee during the daytime and Peart and Lifeson late into the evening, Lifeson cracking open his Tupperware box of weed and going to work on his guitar parts. In the 70s, though, all three members would crowd into the studio to study the others’ work and throw ideas around, producer Terry Brown keeping a watchful eye through the glass.

“Back then it was all for one and one for all,” says Lee. “We were always in the room at the same time, we were always leaning over each other and making comments and it was very congenial and we were super involved. Whereas 30 years later you want more space and you’re less nervous about leaving Alex alone to do his guitars! It was fun. In later and more recent years, we each have our own hours we like to work, like I don’t like to work in the evenings, but Alex does because he can smoke a joint and get lost in the underworld!”

“Ged and I generally worked together during the days but I always enjoyed the quiet of the evenings on my own to catch up on tracking and exploring other layers for what we had written,” says Lifeson. “Over the years, we’ve developed a great deal of respect and trust in each other’s strong points during our writing sessions. We give each other space to initiate and develop our individual ideas within the partnership and that’s rare. You’ll hear of the petty arguments and jealousies that can tear bands apart, but we were never those guys. It takes a level of maturity and confidence to rise above that and accept a partner’s ideas and how to improve them for the good of the song. And we were always about what was good for the song.”

And A Farewell To Kings had them in spades. It would be their first gold album in the US and would give them their first hit single, in the shape of Closer To The Heart, the polar opposite of Xanadu in scale, scope and structure, but destined to become as much a part of their live show as the Coleridge‑inspired epic.

“I remember when we had to bring it back into the set for the Rio shows, as there was such a demand to hear it and we’d stopped playing it for a while,” says Lee. “It’s always resonated with people for some reason, and it was a hit as far as we’ve ever had a hit. It got us on the radio, the kinds of radio that would never normally associate with us, so it was as close as we ever came to a pop song, especially at that point. Over here in the UK it had that effect, and in the US too.

“It has that folk protest song vibe too. That’s the first time Neil had collaborated with another writer, Peter Talbot, so it was pretty pivotal in all sorts of ways. I don’t recall how we met Peter – he lived on Vashon Island in the Pacific North West, and he had a real West Coast, hippie lifestyle. He was married with a little kid and we’d go visit them on the island and watch them smoke dope with their kid, and I thought that was really strange, being high with a young kid. That just seemed different somehow…

“Neil and Peter got real close: they became real pals, they had lots of things in common,” Lee continues, “they thought about a lot of things in the same way. He gave some poems to Neil and Neil took them away with him and one of them he eventually hammered into Closer To The Heart. So really, Closer To The Heart was inspired by that guy.”

The album also saw the band’s ever-escalating interest in synthesisers and Minimoogs bearing fruit. Electronic instrumentation was adding colour and textures to the band’s songwriting.

“That’s true, and it was liberating and exciting to hear more sounds and textures coming from the band,” says Lifeson. “That grew to become a monster in the ensuing years, especially when we played live and Ged would be stuck at his keyboards at some points in the show, but it was always satisfying to come off stage knowing you worked extra hard to create that wall of sound and hear the appreciation from the audience.”

“We were in the embryonic stage with the synths at that point,” says Lee, refilling our glasses of wine, swirling his gently, taking a sniff and then a gulp. “There’s definitely more Minimoog on …Kings, but it’s mostly bass pedals, synths and some white noise, not a whole lot of string sounds by this time. We did attempt a couple of things in some of those songs, but not much. So it’s pretty Minimoog-y. That’s a technical term, right?

“The bass pedals opened up the possibility of a second guitar at times, which is what happened in Xanadu – there were definitely more colours going on and it opened up Alex to play single lines a bit more, melodic lines, because I could fill in the background with guitar or bass pedals. So that was a big sort of change in the way we thought and the way we approached our songs and the way we wrote.

“That’s partly why I think Farewell was an important album for us. We did go into new territory with that record and it was a big step down a road, sonically, that we didn’t really ever let go of. Two albums later we’d make Permanent Waves!

“When you open that door of the synthesiser and the keyboard world, that was a Pandora’s box for us, and after we’d opened it, all kinds of stuff came out over the next few years, but that’s what made it glorious as a guy who was in the middle of it all.

“I learned a lot; I was learning a lot,” Lee continues. “I was always challenged and I was very stimulated and the end result was A Farewell To Kings, so I guess it was a pivotal record in that regard.”

It was also the only time in the band’s career that the lead-out track would act as the introduction for the record that would follow it (though the By-Tor character that had appeared on Fly By Night did reappear on the follow-up Caress Of Steel album). Ask Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee now if they had any idea that Cygnus X-1 would be the spark that fanned the flames for the Hemispheres record and you’ll get a bewildered shrug.

“No, we didn’t know it was going there,” says Lee. “Neil may have had that in the back of his mind, this bigger thing brewing, but at the time it was just what came along.”

Listening back to it now, it’s still a dazzling, complex affair that appears to end in disarray, with the Rocinante spaceship perishing at the heart of a black hole.

To describe the arrangement as dense would be to undersell it somewhat. It’s a grandstanding example of archetypal middle-stage Rush – music that’s sublime, histrionic, fantastical and musically daunting, but still, strangely, very listenable, and almost impossible to play. It’s also a prime example of why you still see so few Rush cover bands – imagine trying to jam through that track in a rehearsal space! That, though, is exactly what Rush did.

“That was something we jammed out,” confirms Lee casually, as if he’s talking about a 12-bar blues riff the band might have worked up, “I think that grew from all three of us sitting in a room together, trying to work it out. I had an idea for the opening and Neil started playing the drum part and then, just as any band does, and perhaps that’s the organic nature of a band like Rush, you figure out the part and you put it together.

“Neil had this story in his mind and we loved it – it was really expressive for us. That whole idea of using sci-fi stuff really worked for Rush because there are no boundaries, there are no limitations, you can use all your goofy, weird sounds because that’s what’s happening out in space. Didn’t you know that?! There are all kinds of echoplexes out in space – they’re dotted around like star systems. There are always Marshall stacks and Serbian guitarists making noises through echo machines in space.”

“It was an intense jam,” reveals Lifeson, “and I loved the heaviness and dynamics of the track as it came together. I also remember being very high while we put the intro atmospherics together and, let’s be honest, it wasn’t for the first or last time!”

“Those things are always fun to do,” says Lee. “You do have that serious side that wants it to be right – like, ‘How do you know that weird sound is better than that weird sound?’ You have to have a modicum [of restraint] – this is my serious face – you have to do that, otherwise it’s just chaos. You have to have parameters to an extent, because technology is the tool and it can be the thing that destroys you. You have to wrestle with it, and I think artists of every stripe have had to do that since the beginning of time.

“Painters, your paints are your technology, your brushes, so you have to work out a way to use those things to express what you want to express, so it’s easy to go over the top, but you don’t know you’re going over the top until you’ve got there! It’s like anything – when you’re trying to get your idea down, you can’t edit at the same time, you have to put it down and let it be overblown and then take a step back and see if it is or isn’t.

“And you have to remember, it wasn’t a brutal record to make, it was fun, things came together relatively quickly. We ended it up by going into Advision Studios in London to mix it and I was so excited because that’s where all those great Yes records were made, and those ELP records. It was well respected and a well-used place by a lot of the guys that we admired, so that was a thrill for us, and it was nice to get out of the country and into London for a few weeks.”

Given the mix of songs on the record, the epically long and overblown juxtaposed with shorter and more succinct material meant that balancing two sides of vinyl was something of a challenge: the grandiose abutting the understated, but also making the whole thing fit and flow.

“But that’s the thing I really miss,” says Lee. “Back then, one of the great pleasures, and one of the toughest things, was sequencing. That was an art back then – you had two sides, you had two chances, you had a beginning and an end twice, and so that was cool because you had 15 to 20 minutes to work with and you had this whole feel, and then you could change this feel in the second half if you wanted to. And we were the kind of band who revelled in that way of expressing things. I think that really came to bear on Farewell…, the way it sits together as an album.”

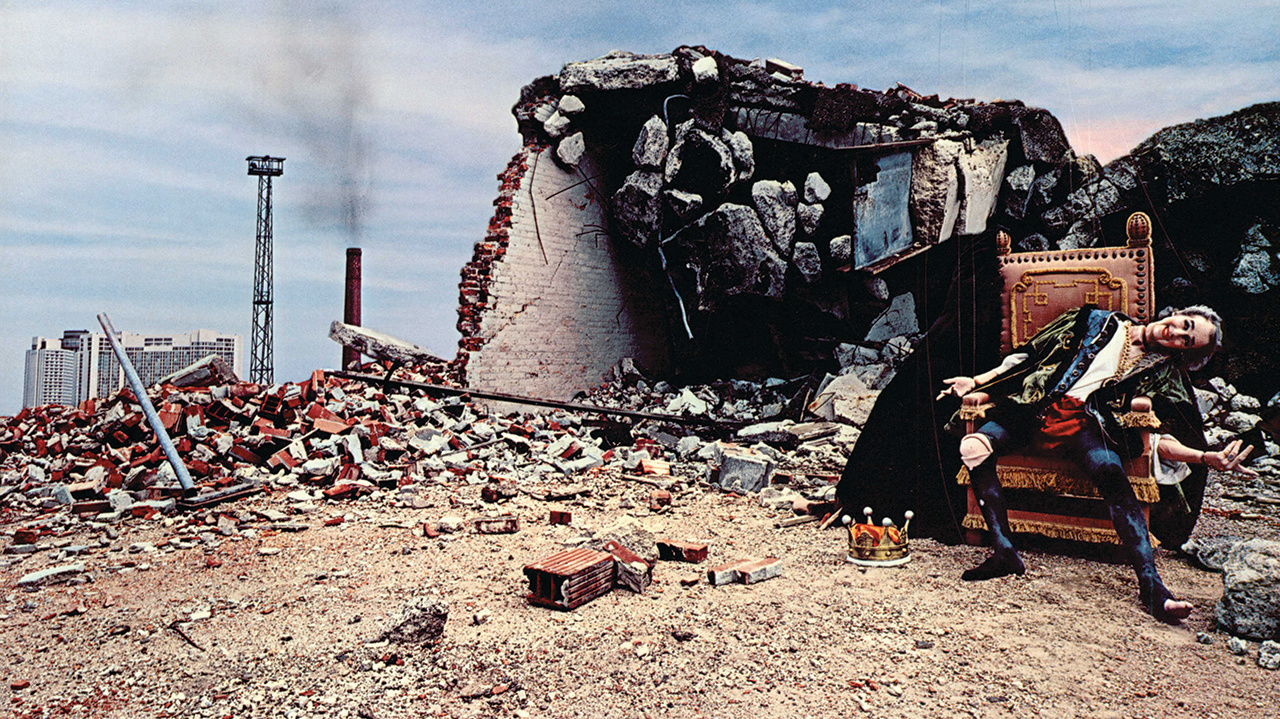

As much as the band and Terry Brown played their part, long-time collaborator and cover artist Hugh Syme’s depiction of the clown king, lost and alone in the urban wasteland, gave the whole album an unsettling undercurrent.

“That worked for us because there’s a subtle theme that goes through part of the album that’s all about loss,” says Lee. “We have this thing: where are the next people we want to look up to going to come from? Which is not an uncommon theme in Rush music – it’s something that comes and goes with us. It’s like everybody needs people to look up to, everybody needs people to emulate or be inspired by, and they’re hard to find. And so it’s that whole ‘trying to find the positive point of view when all around is not so positive’, shall we say?”

He sits back, one more swirl of the glass, a final gulp.

“The whole concept of the album is disintegrating right now, but they’re very much time capsules – where you were at musically, socially and what kind of things you were talking about. They’re frozen in time, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have said what you said – you can’t take that back. There were protest songs on there, sociopolitical comment, songs about space!”

The following summer they’d be back at Rockfield to try to recapture the magic of A Farewell To Kings on Hemispheres, their last album of the 1970s, and what would become a real turning point in their music and how they made it. 1980’s Permanent Waves sounded like a band renewed, but its seeds had been sewn with A Farewell To Kings. Though that was all to come, Geddy recalls their return trip to Wales as they tried to capture that elusive magic one more time.

“We enjoyed our time there a lot, so much so that we went back, like idiots. Never go back. You can’t do that –history doesn’t repeat itself…”

A Farewell To Kings – 40th Anniversary is available from December 1 via UMC. See www.rush.com for more information.

Nine facts about A Farewell To Kings

Rush men Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson forming new band?

Watch 12-year-old Indonesian girl's triumphant version of Rush classic YYZ