Recently U2 gave their Songs Of Innocence album not just to everyone who wanted it, but to also everyone who didn’t want it. It felt like the moment that the music business had finally jumped the shark, given up any pretence of control of its future. If one of the world’s biggest bands was promoting the message that music was essentially valueless, what hope was there for everyone else? The once-mighty LP had been reduced to the status of junk mail to promote the launch of a mobile phone. The sense of music as commodity rather than art had never been higher.

Yet the same moment that Songs Of Innocence was landing unbidden in 500 million iTunes accounts, pressing plants across Europe and America were working flat out to meet a new and ever-rising demand for vinyl albums, the prehistoric form that had apparently been consigned to the same dustbin that contained black-and-white television, the C90 casette, the pocket calculator and the digital watch.

Ours is the only generation that will know this dichotomy, because we have lived through the change, and understand the difference between music in a physical form and in a digital one. The vinyl revival is about more than just an emotional connection to the past. It’s not pure nostalgia. Instead it’s about reclaiming the importance of music, of making it a more central experience in our lives again. Vinyl, more than any other form invented, reinforces the bond between artist and listener. It rejects superficiality and makes music cherishable. Looking back through a vinyl collection can be like looking back through an album of old photographs: there’s a lifetime held within it.

A glance at the market shows how strong the love is right now. Jimmy Page’s epic series of Led Zeppelin remasters have just emerged in handsome new editions; Pink Floyd’s The Endless River will be available as a double album in ‘heavyweight’ 180-gram vinyl with gatefold and full-colour inner bags; Black Sabbath’s 13 – one of 2013’s biggest-selling vinyl releases – is now out as a Super Deluxe Box Set; and so on. Almost every landmark rock record has been given the treatment or is due for it, in lavish style and at premium price. New albums too: current ones by everyone from Mastodon to Stephen Dale Petit are being released on those big black plastic discs that once bordered on extinction.

The first half of 2014 saw vinyl sales in the US rise to four million units, a growth of 40 per cent on 2013, which in turn was 30.4 per cent higher than 2012. Total US sales for 2014 are now projected to be 8.3 million. In the UK, BPI analysis shows a similar pattern, albeit on a smaller scale. In 2013, vinyl album sales reached almost 800,000, the highest since 1997, and an increase of 101 per cent on 2012. These are still tiny slices of an overall market worth £1 billion annually in the UK and $7 billion in the US, but the contrast with the falling popularity of CD means that sales have become commercially significant. The albums that drive those sales are a good indicator of the different groups of buyers. In the UK, 13 was credited as a key release, alongside records from Arctic Monkeys and Daft Punk. In the US, Jack White’s album Lazaretto became the first record to reach No.1 on the Billboard chart with significant vinyl sales since Pearl Jam’s Vitalogy in 1994 (40,000 of the 138,000 copies of Lazaretto sold in that first week were vinyl).

Stephen Godfroy co-owns Rough Trade Records, whose shops hold large stocks of vinyl, and are selling the majority of it to younger buyers: “What we’ve found, if anything, is that digital music – download and streaming – has led to the growth in vinyl sales because they’re very complimentary formats. The disposable nature of digital music tends to add more value to music as an artefact. And vinyl, being the quintessential example of music as an artefact, is benefiting from that.”

Long before Mikael Åkerfeldt found fame as the leader of Opeth he was an angry young kid trying to clear himself a space in the world. Buying records helped him to do it, and his vinyl collection is ongoing and vast – “obsessive” as he describes it. “I am,” he says, “a product of my record collection.” He even jokes that he doesn’t like the vinyl revival because it “increases competition” for him in his endless search. In turn he has been able to release Opeth’s records on vinyl, and loves every part of the process. “I even like the way you can tell the slow parts of a record by the darker colour,” he says. He is probably the only man in the world to have successfully traded an Arnold Schwarzenegger poster for a copy of Sodom’s Persecution Mania.

“I was restricted to buying one or two albums per year, which made it feel like you’d won the lottery and you treated the record like a piece of gold,” Akerfeldt says of his childhood. “I listened to each new album till I knew it by heart. It became part of my life. It wasn’t like it is today, when consumers just download a few songs and then you can discard them just as easily because there was absolutely no effort put into obtaining it. The format has become worthless in the sense that the availability is there wherever you are – for free. Vinyl feels, looks and sounds like it’s got some history and value that you simply don’t get with any of the other formats.”

It would be easy to see the rebirth of vinyl as a virtuous circle of good business, a realisation of the notion of a ‘portfolio’ of revenue streams that will enable the new, leaner music industry to survive. Yet that would be to disregard both the roots of the revival, which began with tiny independent labels meeting a need that vibrated at street level, and the feeling that fed it, which is one of anti-establishment rebellion.

“I believe it’s a form of resistance to the established music industry as a whole,” says Derek Oliver, who runs the cult reissue label Rock Candy alongside his long career in A&R and as a music writer. “Fans have been told by the corporations what to buy for years and what format to listen to it on. You had to listen to their music on the format of their choice. I think consumers are totally disillusioned with the notion that music doesn’t have to come in physical form or with any packaging.

“The popularity of vinyl among young consumers is tantamount to a revolt. In effect the proletariat have not only usurped the corporations by forcing them to return to exotic physical packaging, they’ve also frustrated their desire to exterminate physical distribution. The corporations would much rather deliver content down a phone or satellite connection than sell it via a brick and mortar record store or the postman.”

It’s true that the major labels were seduced by the arrival of CD in the 1990s, and then subsequently blind-sided by the digital revolution, yet it’s also fair to say that they have embraced the renaissance of vinyl as a part of their own heritage.

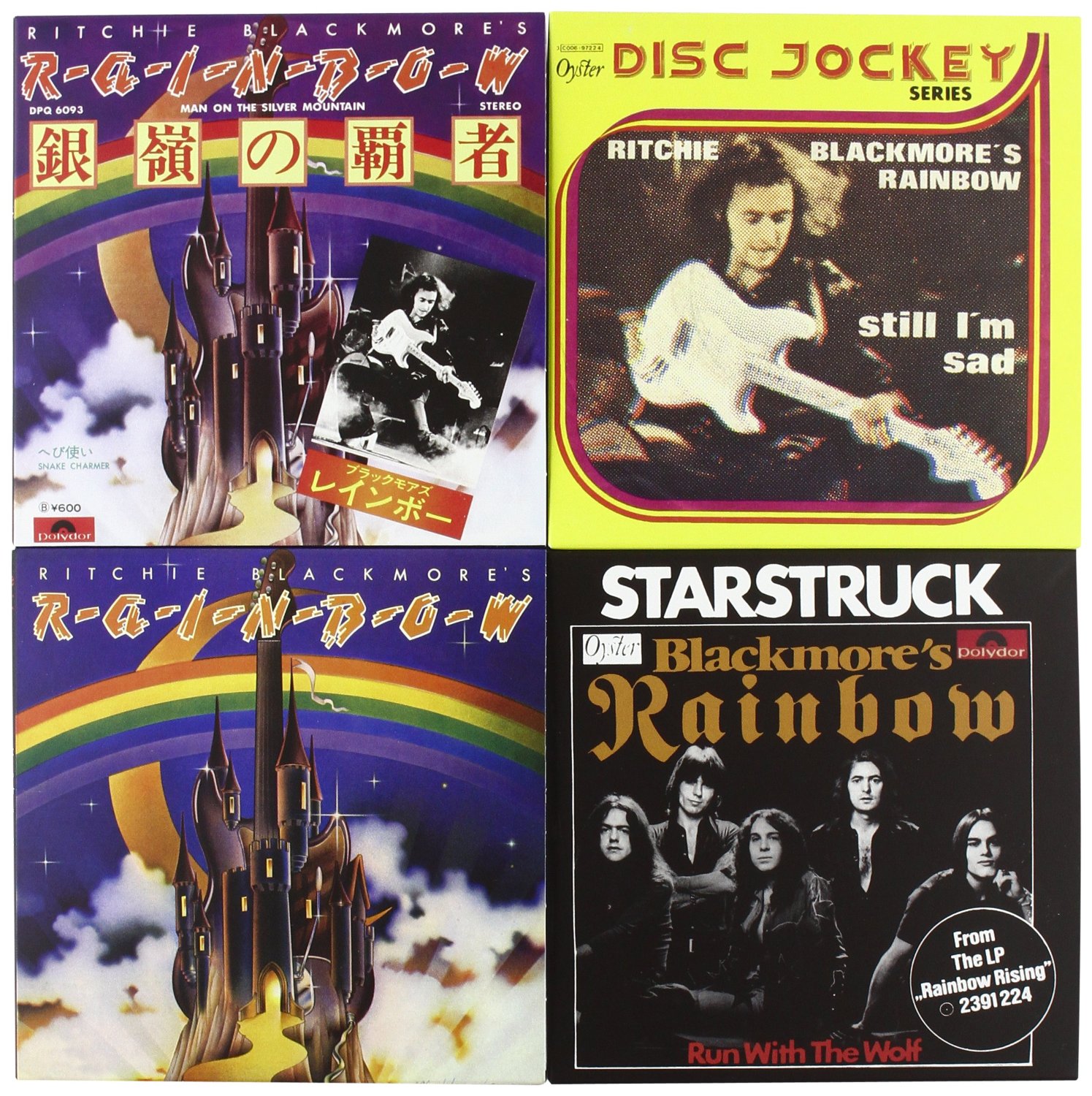

“We never completely stopped producing it,” says Andrew Daw, who has been head of Strategic Marketing at Universal since 2007. Although a confirmed rock fan, he arrived there from a background in dance music, a genre that has always had vinyl at its heart, and so he understood the format implicitly. Under his stewardship, Universal’s Back To Black programme of vinyl reissues has flourished . The highlights of a crammed current schedule include studio album box sets from Rainbow and Lynyrd Skynyrd, a series of picture discs from Megadeth and Rob Zombie, and a deluxe vinyl reissue of Queen’s Forever which features previously unheard material from the Freddie Mercury era.

“Vinyl was a sort of dormant format,” Daw says. “When I took over we had put out Johnny Cash’s American V. I got out my old turntable, and my nephew, who was 13 at the time, just stood there with his mouth open when I was playing the record. You get so used to compressed files that you forget how a record sounds. We started Back To Black, where we issued vinyl with the MP3 files. It seemed out of order to me that you could side-load a CD into your MP3 player without extra cost, but you can’t with vinyl. We started that up in 2007 and we’ve done masses with it. I flatly refuse to let us make vinyl at less than 180 grams. As far as possible we want to reproduce the original rather than worry about the cost of the product.”

Daw sets great store by the detail, organising training sessions for staff so that they can understand better the process of producing vinyl, buying back examples of sleeve artwork on eBay and working closely with a design team that goes to great lengths to recreate exactly the original releases. Interestingly, he points out that the revival has its greatest hold in France and Germany, which are behind only the US in terms of the demand for vinyl.

Universal aren’t unique. Every major label is back in the vinyl game. As was the case in the glory years, they are orbited by a growing number of clever and adaptable independent labels that have seized their own sections of the market, usually in issuing new product from smaller bands.

Third Man, established by Jack White in 2001, “excavates rarities” via a subscription club and presses bigger artists such as Seasick Steve and Neil Young in a variety of colours and styles. California’s Alive Naturalsound offers limited editions in coloured vinyl for fans of punk and garage rock, with the pressing process often making each individual record subtly different and more collectable. Recent releases include new albums from psych-riffers Radio Moscow, and Paul Collins, the former leader of LA power-pop band The Nerves, who wrote Hangin’ On The Telephone, later covered by Blondie.

“My theory is that the rebirth started around the time the economy tanked,” says Alive Naturalsound co-founder Patrick Boissel, who began the company in 1994. “A lot of people sold their old vinyl collections, and suddenly albums that were previously only accessible to a small group of collectors were now available to a new generation at a decent price. Add to this the hipster factor, the new cool kids rebelling against digital and streaming, and you end up with the current trend. The [major labels] are now saturating the market with tons of reissues. Let’s just hope they won’t wreck it.”

The vinyl format is almost mystically allied with the shops that sell it. They seemed to be disappearing together, but another of the revival’s roots lay in the shops’ appeal. The inauguration of Record Store Day in 2007 (which was in turn inspired by Free Comic Book Day) was the first intimation that all of the disparate artists, labels, buyers and sellers could come together and unite behind the wider cause. The 2008 Record Store Day was launched by Metallica at Rasputin Music in Mountain View, California, and by 2013 the movement’s co-founder, Michael Kurtz, was receiving the French version of a knighthood for his role in creating an event that now had the world’s biggest bands lining up to produce one-off vinyl singles. In one way, the idea has become a victim of its own success, creating an artificial trade in deliberately created rarities that has led to some artists pulling out of the process. But as Andrew Daw says, it “remains important for keeping the awareness of vinyl high, but it’s not representative of the whole market”.

Demand can outstrip supply. One of the side effects of this renaissance has been the need for the hardware that both manufactures the records and plays them. United Pressing, in Nashville, has just added 16 presses to its operation, upping daily output to 60,000, while, oddly, the Church of Scientology purchased at auction the last few original ‘metal mother’ machines that imprint the vinyl, apparently to preserve the speeches of their founder L. Ron Hubbard. Pressing remains a concern for labels, with demand far outstripping supply. Waiting time for a slot at a pressing plant can be as long as four months, and with vinyl becoming an increasingly important part of first-week sales, it can affect release dates.

As with the hardware needed to manufacture and play vinyl, the places to buy them are re-emerging, slowly. While online sales will always bite into their trade, the ritual of record shopping is part of the magic, and in the UK shops like Fopp and London’s Piccadilly have made vinyl a strong part of their “customer experience”. In the US the trend for vinyl has even seen it appearing in the tragically fashionable American Apparel stores. Just as record companies have had to adjust their model, so shops have too. The days of vast stores with huge stocks of back catalogue are gone, lost to the online world, but Fopp’s mix of vinyl, CD, DVD and books is a viable and attractive offer to customers.

Sales of turntables and styluses are also on the up once again. “Portability is important to people,” says Daw, “but at home we’re noticing that they increasingly want quality, be that with vinyl or with HD digital files.”

Vinyl remains an anachronism, and sales will always be limited by the constraints of modern life. Technology streamlines our existence, and it rarely goes backwards. Classic Rock subscriber Richard Mullineaux buys around 50 albums a year, but at the moment all on CD.

“It’s about portability as much as anything,” he says. “The car is one of my main chances to listen to music, so if I get a journey of an hour I’ll take three CDs. I’ve still got around two hundred and fifty vinyl albums, and I’ve got a good turntable, but there’s no convenient room at home to set it all up. I’d start buying vinyl again if and when I can do that.”

Vinyl will never again scale the heights of the 1970s and 80s, when it fitted more easily into a lifestyle that’s now passed, but it still feels more vital, more meaningful and more soulful that the random dumping of music into half a billion iTunes accounts at the touch of a button.

“There’s millions of collectors all over the world and most of these will never stop,” says Mikael Åkerfeldt. “It never went away for us, so obviously it’s here to stay. At least until all of us are gone.”