There were several reasons for Slade’s success,” the band’s guitarist and fabled ‘Superyob’ Dave Hill informs Classic Rock, in a Black Country accent thick as treacle. “Most importantly, we had great songs. But the whole country recognised us as four working-class guys who’d got glammed-up, stuck their fists in the air and were telling everyone to have a good time.

"We were no-nonsense. We didn’t take ourselves seriously, and we were proud to be British. I think people could relate to that, whether you were a granny, a teenager or a three-year-old. And of course we had a violin. Until then there were no rock records with violin.”

Fronted by the foghorn-voiced Noddy Holder, always resplendent in ever-changing outfits that included a top hat bedecked with mirrors, between 1971 and ’76, Slade notched up 17 consecutive UK Top 20 hits of which six – including Cum On Feel The Noize, Mama Weer All Crazee Now and Take Me Bak ’Ome – reached No.1.

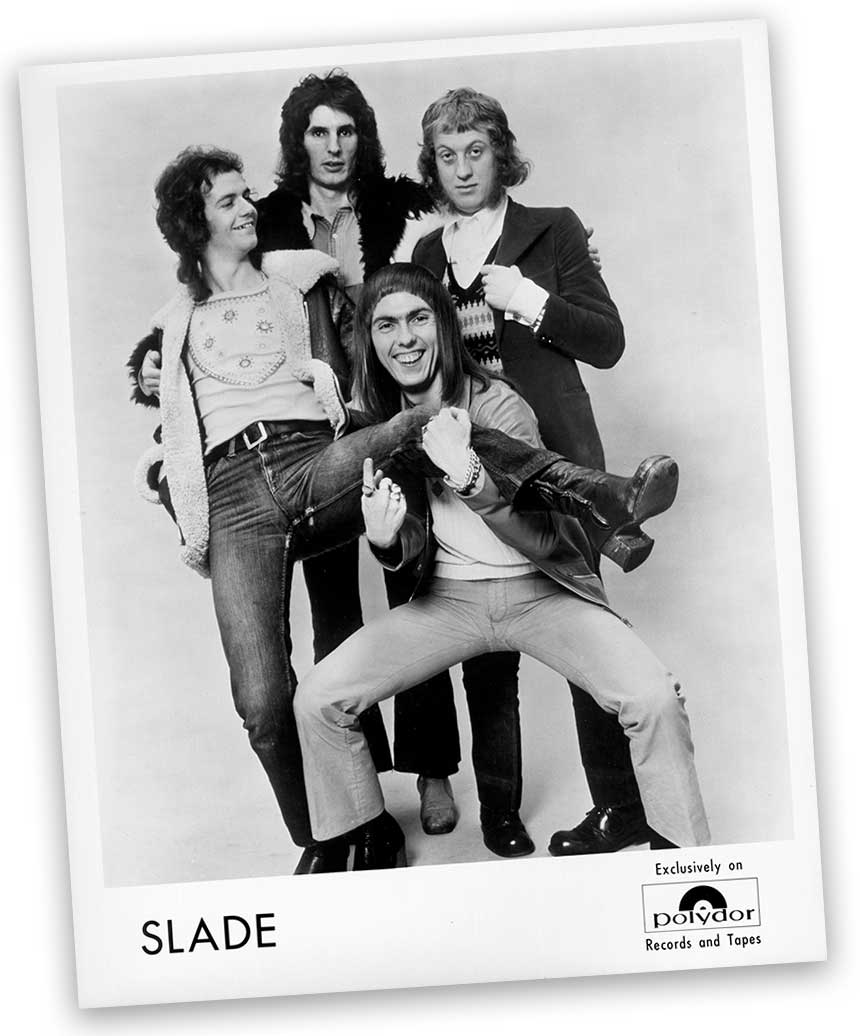

Classic Rock spoke to all four original members to get the band’s roller-coaster story – their journey to the top and back… twice – told in their own words.

Dave Hill: I first met Noddy on a ferry heading to Germany in 1965. He was with his band Steve Brett & The Mavericks, and Don [Powell, drums] and I were with the ’N Betweens. We asked if Nod wanted to join the ’N Betweens and he said no.

Noddy Holder: I was earning good money with the Mavericks. We were doing R&B, soul and Chuck Berry and Little Richard-type songs. The ’N Betweens were about blues and very little else.

Hill: Don and I wanted to form a band that was more like The Beatles. At the auditions this very young lad arrived carrying a Paul McCartney bass. He looked about fifteen years old. He said his name was Jim Lea.

Jim Lea (bass, violin): I was still at school. I looked like a boy and I was a boy, but I played like a man. I was self-taught on bass. At the audition I was so intimidated. I had turned up with my bass in a carrier bag. They asked: “This is a professional group, where’s your equipment?” I lied and said I had some but couldn’t bring it on the bus.

Hill: When he started playing I’d never seen anything like it – it was like Jimi Hendrix had got hold of a bass guitar.

Lea: I played really, really fast just to show what I could do. I’m a very unconventional player; I was bending strings and using distortion. When Dave realised what was going on he wanted it too.

Hill: Just after we found Jim, I bumped into Nod inWolverhampton. He’d left the Mavericks. I said I was looking to form a band with three lead guitarists, including Jim who played like a guitarist. Nod lived opposite a pub called the Three Men In A Boat, and he suggested a ‘secret rehearsal’ there because the ’N Betweens already had a singer, Johnny Howells. At his front door Jim was holding a violin. I thought: “Blimmin’ hell, he plays bass like Hendrix and violin too!”

Lea: When I was first introduced to Noddy at the door I misheard his name. I was calling him ‘Nob’ for the first three months. Hill: We ran through some soul songs that everyone knew, and the chemistry between us was instant. It felt right.

Don Powell (drums): The first song we played was Mr Pitiful by Otis Redding. It just clicked straight away. We were like little kids giggling.

Lea: But with Johnny Howells that made five. Johnny decided to leave after a gig in Cornwall, and we thought about finding a replacement. When they asked my opinion, I pointed out there’d be more money as a four-piece. And that was that.

From 1966, The ’N Betweens released a run of singles that sank without trace outside ofthe Midlands, including a cover of the Young Rascals’ You Better Run that was produced byKim Fowley, the American svengali who went on to mentor The Runaways.

Three years later The ’N Betweens signed to Fontana Records, who demanded a name change to Ambrose Slade. Adebut album, Beginnings, and two further singles all flopped. And then the band met Chas Chandler, the former Animals bass player who had managed and produced Jimi Hendrix.

Lea: Kim Fowley saw us at a club in London. He was six feet tall with a feather boa. He got us to record You Better Run but, coincidentally, Robert Plant had just recorded the same song with his band Listen. Neither was a hit.

Holder: Despite the knock-backs we never thought of stopping. We knew we were good. From day one we were a great live band, and that carried us, and being paid cash-in-hand for gigs got us through some hard times.

Powell: If one song failed we’d just go on to the next one. Splitting up never even entered our minds.

Hill: We’d had no idea of how to get into the charts. We were going into shops and buying our own records, but that got us nowhere. Chas Chandler took us on, and among the first things he did was tell us to become skinheads. He said: “You’ll make millions, you’ll be stars.” My reaction was: “Oh no! I love my hair.” Skinheads were into ska music, and there’s us playing rock with a violin player. It was never going to work.

So Chas let us re-grow our hair. That’s where I got the famous fringe I had. We had been ending our gigs with the Chuck Berry- [popularised] song Get Down And Get With It, and Chas said to record it. The boot-stamping helped to define our sound.

Holder: Nobody liked the name Ambrose Slade, so when Chas suggested simplifying it we were relieved. Chas could be a hard taskmaster, and one day he told us: “You’ve got to write your own next single.” He paired Jim and I together. Jim came to my mum’s house with his violin, and we knocked off Coz I Luv You in twenty minutes.

Hill: When Chas heard it he said: “That’ll be top three, definitely.”

Powell: We were just four scumbags from Wolverhampton but we made it on to Top Of The Pops, and it stampeded to Number One. After that, Jim and Nod just rattled them off.

Holder: I had scribbled down the lyrics in Black Country phonetic spelling, and that became a gimmick. Before we knew it we had this treadmill of hits. Chas was constantly on Jim’s back for the next single. But we’d go on Top Of The Pops, and the following day the whole country would be talking about us.

Hill: A lot of effort went into my Top Of The Pops outfits, especially the ‘metal nun’. I think Stevie Marriott nicknamed that one.

Holder: Jim said: “I’m not going on television with you dressed like that.” He actually walked off photo sessions when he saw what Dave and I were wearing.

Hill: My response was always the same: “You write ’em, I’ll sell ’em.”

When Mama Weer All Crazee Now became their third UK chart topper, Slade’s graft and self-belief had paid off. They were the most popular band in Britain. Just as things were looking rosy, on July 4, 1973 drummer Don Powell was involved in a car crash. It left him unconscious for six days, and his fiancée Angela Morris was killed. In the aftermath, the band almost tore apart.

Powell: Even today I’ve got no memory of what happened. Your brain switches off, and that’s probably a good thing. Afterwards the band had to put up with a lot from me.

Lea: The crash affected Don’s memory. One night, leading into Skweeze Me, Pleeze Me, he said: “Jim, I don’t remember how it goes.” I told him to count four beats and just keep going.

Hill: We responded with a song that we thought could become a moderate hit. But it took on a life of its own. I loved that Merry Xmas Everybody doesn’t have jingle bells plastered across it; it’s a song about family, presents and fun. That song lifted a nation.

Lea: Nobody in the band wanted to record that song. When I first played it to Noddy he told me to go away and have sex with myself. But after Nod added his lyrics it came to life.

Powell: Ah yes, ‘that song’ as we call it. It’s true, nobody wanted to release it. But Chas told us: “I don’t care what you lot say, this is coming out.”

Holder: The miners, gravediggers, electricians and bakers were all on strike, and the telly was going off at ten p.m. Glam-rock was a response to that. Merry Xmas was the height of it all. I still can’t believe we sold 350,000 copies in a single day.

Powell: It went gold on the first day of release. In an elevator this bloke said: “I’m so fed up of this record.” When I turned around and looked at him he went blood-red.

Lea: Early on I’d instigated a conversation with the guys about how we’d deal with fame when it came. We’d been driving around with no hits for five years, and we vowed to stay exactly the same. Everyone agreed with that.

Powell: The four of us were all living with our mums and dads at the time, and each of us kept the others’ feet on the ground.

Holder: Yes, we were making lots of money, but don’t forget that tax [for top earners] was at ninety-three pence in the pound.

Hill: In 1973, outside of America we were probably the biggest band in the world. We had ticked all the boxes. It was time to try something new.

The first of these was the band’s film, Slade In Flame, a dark semi-autobiographical piece about a fictional group called Flame. At around the same time, Slade’s singles became mellower and less gonzoid. And it was decided to take a genuine crack at the US market.

Holder: America was the golden goose, but you had to break the place by touring.

Powell: Our records were too heavy for AM stations and not quite hip enough for FM.

Holder: We slogged and slogged there for two years, but it didn’t translate into record sales. Big bands that came out later on, like Van Halen, loved us. Even Kurt Cobain. But it didn’t work for us until the following decade.

Hill: Kiss were there in the crowd, watching us and gathering ideas. I mean, listen to Crazy, Crazy Nights.

Lea: I’ll tell you who else was in the audience – the Ramones.

Hill: We were monster big [at home] but [US] audiences didn’t know what to make of us. With our platform boots we looked like we’d dropped out of the sky. When we got home the press called us Yankee doodle dandies. Some fans said we’d deserted them. British people don’t like that, do they?

Holder: We came back a changed band. There was no point in re-living glam-rock, and top hats with mirrors.

Hill: Everyday came out in early 1974. It was our equivalent of [The Beatles’] Yesterday, showing a more reflective side of Slade. Far Far Away and How Does It Feel were also different for us. [DJ] Alan Freeman said he really wanted to hear an album of Slade songs that sounded like Far Far Away, but sadly we never made that album.

Lea: As non-actors, Slade In Flame [1975, the soundtrack album of which included How Does It Feel and Far Far Away] was a big risk, especially as the subject matter was so dark, but in recent times it has received a lot of credit. The BBC’s Mark Kermode called it “the Citizen Kane of rock movies”.

Holder: Suddenly, although we could still fill smaller venues, we weren’t coming up with hits. We knew they were good songs, but they weren’t selling anywhere like they had done before. Lea: When you’re used to your records getting to Number One, Number Two is a miss. That presents a lot of pressure.

In August 1980, the Reading Festival threw Slade a lifeline. With Ozzy Osbourne cancelling three days beforehand, despite having turned them down in previous years, the promoters rang Slade. By this point Dave Hill had left the band and was renting out his Rolls-Royce for weddings.

Hill: I needed to generate some form of business. Chas had to talk me into doing the Reading Festival, so what happened that day was a great relief for me.

Holder: We had no great expectations. We’d all but broken up. Because it was short notice we had no car park or backstage passes.

Lea: It was as though we were in a cowboy movie. It was hot and there was lots of dust. It felt like we were Clint Eastwood. People looked at us as if to say: “It’s Slade, risen from the dead.”

Holder: We’d been warned that we wouldn’t get an encore but, fucking hell, we tore the place up. So they sent us back out. After I asked what everyone wanted to hear – we weren’t going to do Merry fucking Christmas in August – I got them to sing it. The next week we were on the front pages of all the music papers.

Lea: The success at Reading gave us something to cling on to. The following year we did Monsters Of Rock, supporting AC/DC.

Hill: We returned with We’ll Bring The House Down and Lock Up Your Daughters. That period in our history was nice. We’d come out of being dressed up like Christmas trees, and now we were a bit more rocker-y. We toured with Whitesnake and we wanted to appeal to the Donington crowd.

Holder: We thought we were going to have a Number One with My Oh My [in 1983], which would have given us Christmas Number Ones ten years apart. But although it topped the charts all over Europe, in the UK we were beaten to it by The Flying Pickets. That was disappointing.

Hill: Suddenly, CBS in Los Angeles began paying interest in us. Quiet Riot had had a hit with Cum On Feel The Noize, and it made them wonder: “What are Slade up to?” Sharon Osbourne became our manager and Run Runaway went Top 40 in the States. Americans liked its Scottishness. We thought it hilarious when interviewers asked whether the four of us really lived in the big castle that featured in its video.

Against all the odds, Slade were poised for a much-belated breakthrough in the US. Instead, when Jim Lea developed hepatitis C they were forced to return home after playing just the opening night of supporting Ozzy Osbourne. Slade would never quite recover from the crushing disappointment. They retired from the road in 1984, and effectively signed off three years later with the album You Boyz Make Big Noize, although a final 1991 hit, Radio Wall Of Sound, proved there was still juice in the tank.

Hill: As time went by, things just weren’t the same any more. There was a sense of running things down. The record company didn’t re-sign us. Without touring, for me there didn’t seem to be any point in being a band. I still find it difficult to talk about. Nod didn’t want to do it any more, and I understood that.

Powell: The band had run its course. After so long of being together, that felt strange.

Holder: When bands break up it’s usually to do with five reasons – egos, money, drink and drugs, women or musical differences. In Slade’s case it was all of the above. Though Dave and Don were paid for performances, Jim and I received more as writers. That became an issue when there was less money floating around. We hadn’t been getting on for a while, and then Jim started to want more and more control in the studio.

Lea: Someone else told me he [Holder] had said that. But it’s not true.

Holder: My wife filed for a divorce and my dad was extremely ill, so I told the band I wasn’t going to tour any more. They didn’t really like that. Slade had started out as a gang of four happy-go-lucky guys, and it wasn’t that any more. When it stopped being fun, that was it for me.

Hill: For the first few years I used to think there was a chance of reuniting with Nod. But his mind’s made up. There’ll be nothing live from Slade, that’s for sure.

Powell: It’ll never happen again. For me, doing so would soil our reputation.

Holder: The way things are now between Dave and Don [back in February, Hill sacked Powell from the current, post-Holder/Lea line-up of Slade by email], it’ll never happen. I couldn’t do four or five gigs in a row singing like I used to. I don’t think any of us could manage it. We’re in our seventies. And I know that we wouldn’t get on. Twelve or thirteen years ago there was talk of one final tour, but everybody fell out at the meeting. The only time I hear from Jim now is a solicitor’s letter when I’m accused of saying something [in an interview].

Powell: Things are a little easier with Dave now, and I’m planning to form my own line-up of Slade.

Hill: I’m an entertainer, and people still want to hear those songs. There seems to be interest in getting me over to America again. I’m sad at falling out with Don, and it’s hard to discuss without stirring up further animosity, but I will keep on going. I still love it as much as I did picking up my first guitar at thirteen.