B.B. King released more than two hundred singles and fifty albums in a six-decade recording career. He is a towering figure in popular music. Yet, many casual fans can identify only one B.B. King song, The Thrill Is Gone, a 1969 release that reached #15 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

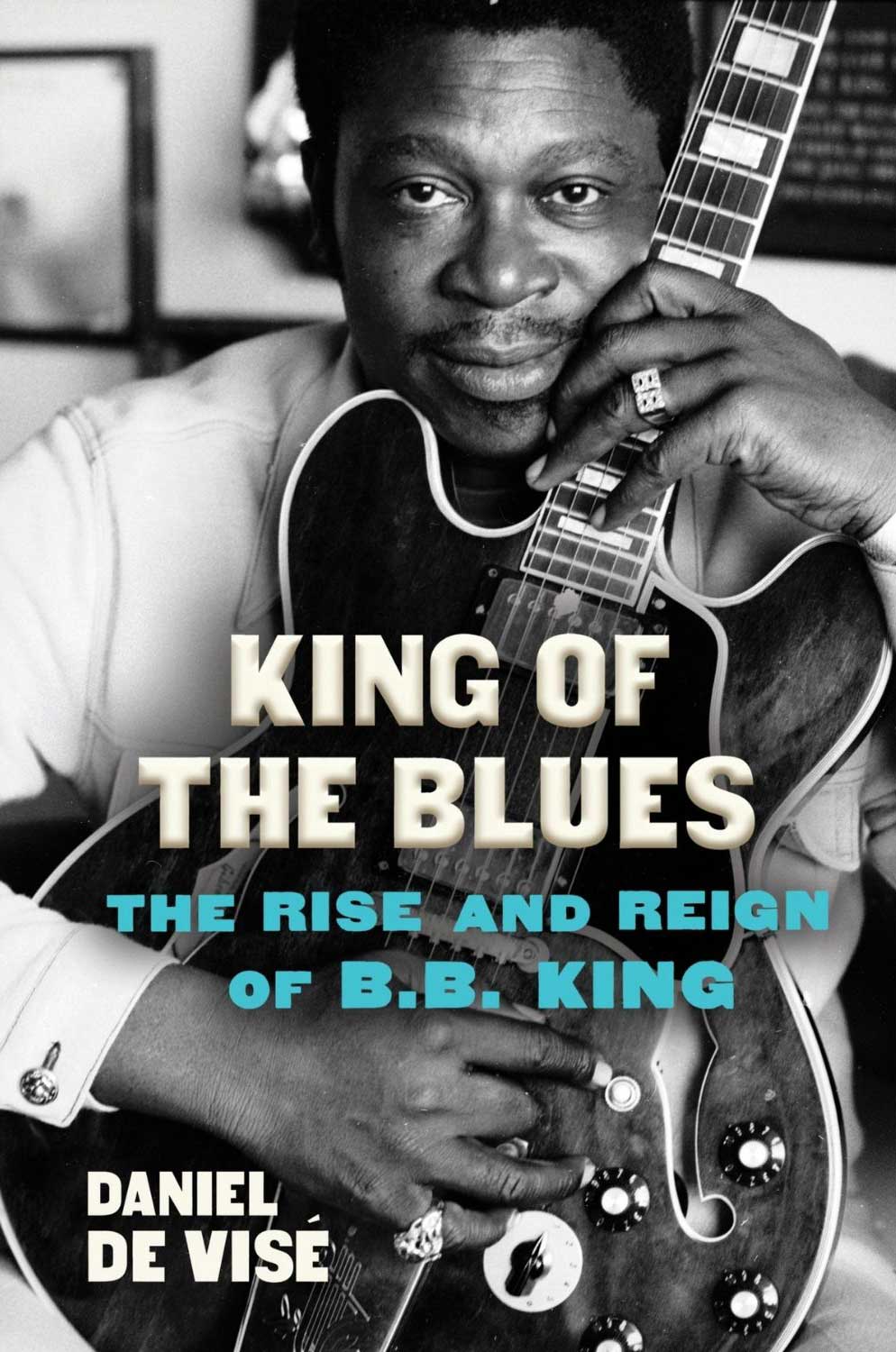

I listened to nearly all of those singles while writing King of the Blues, the first cradle-to-grave biography of the man Eric Clapton called “the most important artist the blues has ever produced.”

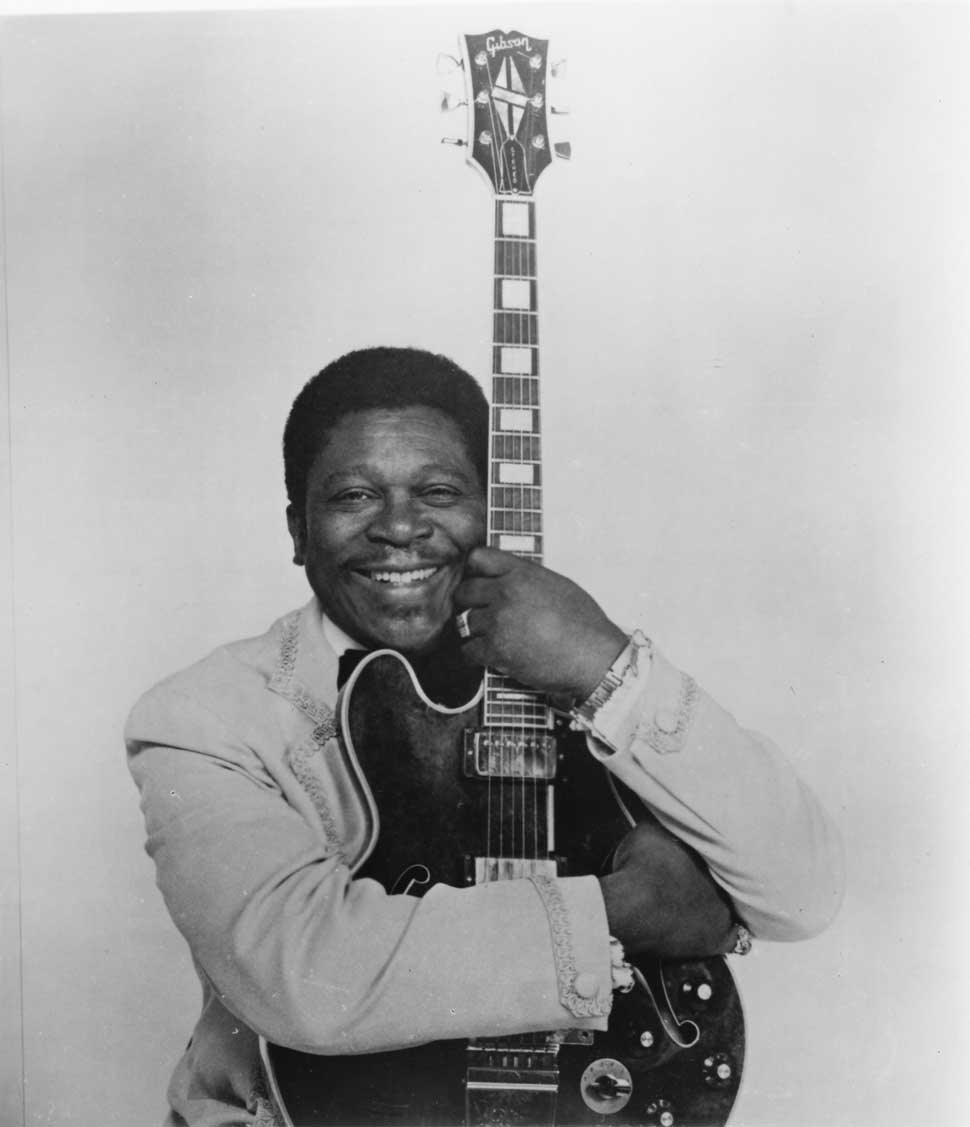

B.B. King started out in the 1940s as a sidewalk busker in the Delta folk-blues mould, singing and accompanying himself on acoustic guitar. Then he went electric, moved to Memphis (in 1949), formed a band and learned to play single-string solos in the style of his idols, jazz-blues master Lonnie Johnson and R&B sophisticate T-Bone Walker. In time, he developed a style all his own, harnessing amplified vibrato and sustain to render solos that sounded like a human voice: Lucille.

B.B. King and his guitar burst onto the rhythm and blues charts in 1952 with the No. 1 single 3 O’Clock Blues. This was three years before Chuck Berry and Maybellene, a decade before The Beatles, a time when guitars and guitarists seldom cracked the charts. Ironically, even as B.B. created a new lexicon of solo guitar virtuosity in the 1950s, the R&B world mostly ignored Lucille and recognized him primarily as a singer. But a new generation of guitarists heard B.B.’s singles and spread his sound. By the close of the 1960s, seemingly every lead guitarist in pop wanted to play like B.B. King.

This playlist traces the evolution of B.B. King as a singles artist, from his first – and occasionally embarrassing – forays into Memphis recording studios in 1949 through his crossover breakthrough, twenty years later, with The Thrill Is Gone. I’ve ordered the songs as they appear in King of the Blues, so the playlist can be used, in effect, as a soundtrack to the book.

Mistreated Woman (1950)

To my ears, this early single marks the recorded debut of B.B.’s signature vibrato. He had recorded four songs in 1949, performances that sound amateurish in hindsight. He practiced hard over the winter, and he entered the Sam Phillips studio in July 1950 armed with a distinctive, stinging tremolo.

3 O’Clock Blues (1951)

Just about every musician in Memphis claimed to have played on this track, recorded at the “coloured” YMCA. The first song to feature B.B.’s fervent vocals and impassioned guitar in equal measure, this mournful dirge shot to No. 1 on the R&B charts, his first national hit.

My Own Fault, Darlin’ (1952)

This performance points to the future of electric guitar in popular music. Freshly divorced and despondent, B.B. turns his guitar all the way up, yielding one of the loudest sounds yet committed to acetate.

You Know I Love You (1952)

Rebounding from divorce, B.B. delivers a mournful shuffle about his departed lover. It became B.B.’s second No. 1 hit on the R&B charts, proving the first had been no fluke.

The Woman I Love (1954)

This obscure single illustrates geometric growth in B.B.’s guitar craft. Lucille mounts a savage, reverb-drenched assault on the blues scale, overwhelming the sidemen. The overall effect is something like Jimi Hendrix fronting a big band.

Everything I Do Is Wrong (1954)

Another overlooked side shows B.B.’s guitar technique reaching glorious maturity. Lucille’s top-heavy tone boasts a new richness, a timbre as urgent as an air-raid siren yet warm and melodic. A decade later, Jimmy Page would ride this sound to global fame.

You Upset Me Baby (1954)

To me, this song marks the emergence of B.B.’s unique voice as a blues singer. In prior years, he’d channeled R&B shouter Roy Brown. Here, he finds his own pace: relaxed, ribald, conversational, lagging gently behind the beat. This was the mature B.B. King.

Every Day I Have the Blues (1955)

Released as B.B. debuted as leader of his own big band, this song became a sort of B.B. King theme song, an opener to thousands of shows in years to come. If you’ve seen B.B. perform, you have probably heard it.

Sweet Little Angel (1956)

This is B.B. at his virile peak, conjuring lyrical images of angels suggestively spreading their wings. The song celebrates B.B.’s new love, Sue Carol Hall, a girl of fifteen who would become his second wife.

Sweet Sixteen (1960)

Big, bold and long (clocking in at more than six minutes), “Sweet Sixteen” ushered B.B. into the 1960s with a commanding vocal set against a floor-shaking bass, anticipating recording techniques of the Woodstock era.

Rock Me Baby (1964)

This single established B.B. King in Great Britain, whose guitar heroes would reintroduce his music to white people in America. The song hinged on a simple riff that would become one of the most familiar hooks in blues.

How Blue Can You Get (1965)

B.B. had recorded this song before, but his spellbinding performance on Live at the Regal rendered it immortal. The big payoff came when B.B. lamented that he had given his woman seven children, and now she wanted to give them back.

Don’t Answer the Door (1966)

This release broke B.B. out of a half decade of doldrums with his new ABC label, which had tried to market him as a big-band crooner. The single was a triumph of mood, a showcase for Lucille and evidence that ABC had finally discovered the great guitarist on its roster.

Lucille (1968)

This ten-minute story-song anchored the Lucille LP and seeded the legend of Lucille, queen of guitars. Oddly enough, B.B. had scarcely mentioned her before outside of his inner circle. Five decades on, a YouTube recording of the song has garnered thirty million views.

Why I Sing the Blues (1969)

This aural explosion of anger and hurt marked B.B.’s first overtly political statement, both longer and angrier than James Brown’s Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud. The song anchored Live & Well, the first of four strong albums with producer Bill Szymczyk.

So Excited (1969)

Completely Well is one of my favourite B.B. King albums. This standout track, anchored by an ear-candy organ riff, ventures into the polyrhythms of funk. Such experiments horrified blues purists but helped B.B. maintain currency across several decades, much like his friend and fan, Miles Davis.

The Thrill Is Gone (1969)

B.B. had carried this Roy Hawkins song around in his head for years before he presented it to producer Bill Szymczyk at the Completely Well sessions. B.B. had raised the key, lifted the tempo and recast the rhythm as Otis Redding-style soul. The bassist and drummer laid down an inspired rhythm, and Szymczyk added suspenseful strings. Thrill would endure as the B.B. King song, the one any casual fan could identify after a few bars.

Daniel de Visé's King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of B.B. King is out now.