This article first appeared in The Blues #4, November 2012.

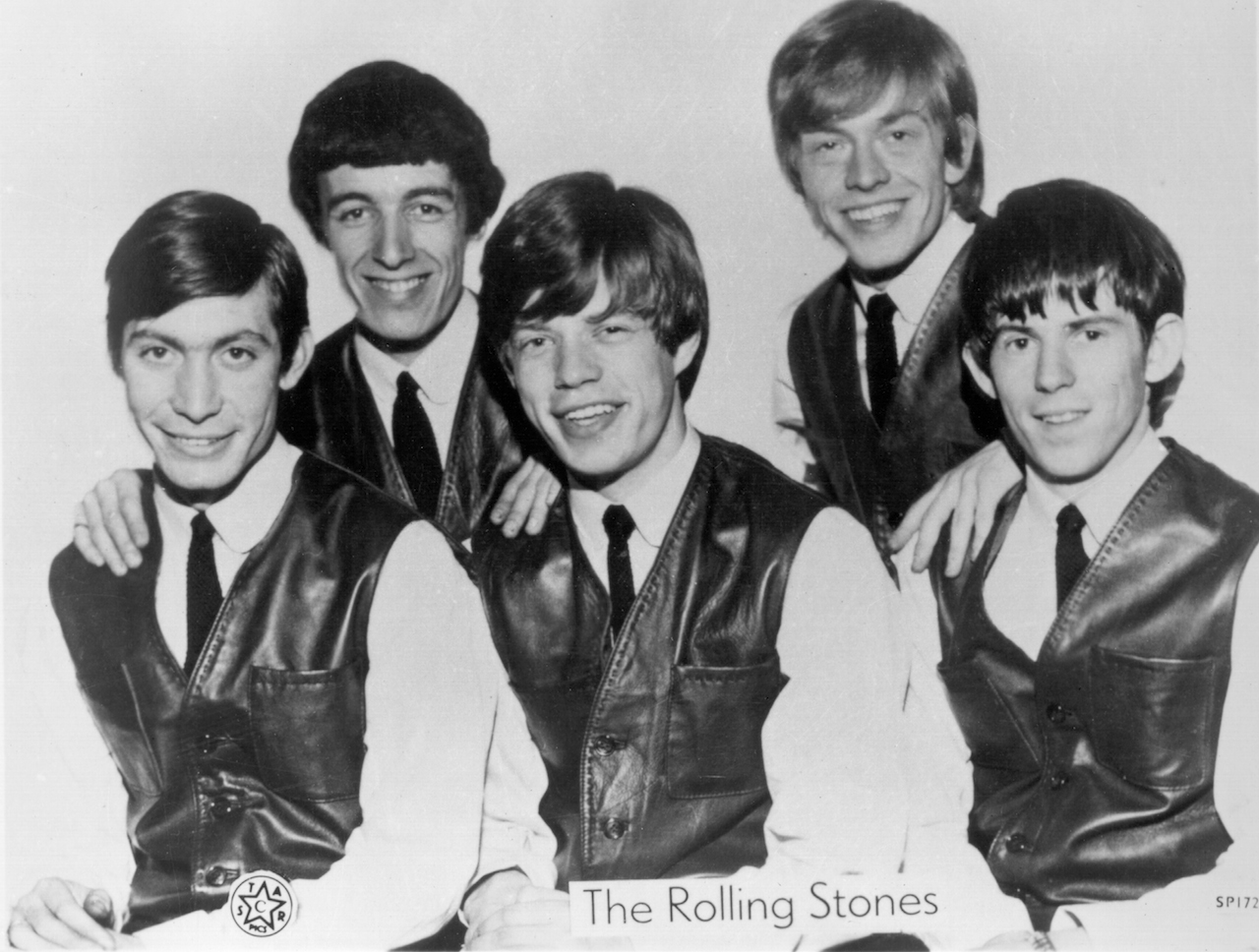

The Rolling Stones are going backwards to go forwards. The miscellaneous effects of a long separation, a major anniversary and the sheer advancing years have mysteriously combined to make them take stock and remember what got them noticed in the first place: being the tightest little blues unit you’ve ever seen.

To talk to them in late 2012 is to realise the same thing they’ve realised themselves: that if they were to have a future, they needed to go back to where they came in. “Okay, you want the blues band, you want the rock‘n’roll, stripped down?” asks Keith Richards, enticingly. “You’re going to get it. It’s going to be fun, man.”

I got together for the latest of many chinwags with the old devils as they prepared for the release of the 50th birthday GRRR! compilation, the premiere of the Crossfire Hurricane documentary and their endlessly teased return to the live stage in London and New York. I’ve rarely seen them as focused as this.

Yes, it’s been five years since the last gigs. Yes, seven since a new album. Yes, there are precisely two new tracks on GRRR!. But, also yes, if Doom And Gloom and One More Shot strongly suggest a back-to-basics attitude and approach, the confirmation is there in what they tell me: that fans who love the Stones at their bluesiest are in for a treat.

“Charlie said we should have the stripped-down thing [on stage],” confides Richards, convivial as ever, in bandana and leather jacket. For once, the obligatory cigarette is not accompanied by the de rigueur vodka and orange. The tape playback almost misses the chink of ice in the glass. He sounds sharp and looks lean, steely-eyed almost.

“I said ‘Charlie, do you realise how much pressure that puts on the guitar line-up?’” It’s easy to say, but at the same time, it’s a challenge, and he’s right. Also, you got the drift, several drifts over the years: too many people on stage. What we try to do on stage is deliver what’s on the record, and there’s a lot of horns and a lot of voices, except they don’t want to see ’em.”

Last year, when I met Ronnie Wood and Charlie Watts to talk about the deluxe reissue of the Stones’ vintage 1978 album Some Girls, the future of the Stones was far from certain. But Wood was being his usual optimistic self. “It’ll be 50 years well spent, I reckon, the Stones’ 50th,” he said, anticipating the anniversary. “A year-long royal wedding, I want.”

Another year on from that, there’s no doubt that the landmark helped them get ship-shape again, even if the anniversary is a little open to interpretation. “In a way, there’s a sense of timing with this band that you can’t really put your finger on,” says Richards, “but there’s a scratch and an itch that comes up, and you say ‘come on’.

“I suppose the 50-year thing is an added spur, not that the Stones think in terms of zeroes. To us, next year would be 50 years because Charlie didn’t join the band until ’63. So we’re celebrating the conception here,” he cackles, “and next year would be our idea of 50 years as a band together. “But the pressure from people, from fans or whatever, from all you guys out there was unrelenting, that ‘come on, we’ve got to do something, man’.”

When the quartet showed up in unison at London’s Somerset House in July for a party to celebrate 50 years since The Rollin’ Stones first played the Marquee Club, it may have seemed more of an enforced photo opportunity than a spontaneous moment. But, after the deep freeze between Richards and Mick Jagger that set in when the guitarist’s autobiography was published, the ice had been broken when they reconvened for jam sessions in New Jersey in the spring. It led to the intense rehearsals in Paris in the weeks leading up to the 02 Arena shows and, to some surprise, new recording.

“I never gave up,” says Wood, often the agony aunt in between the Glimmer Twins. “I knew it would happen , but it’s just such a bloody relief to see we’re all in the fold together. You’d love the atmosphere in the studio in Paris,” he says, conspiratorially. “We’re out in the sticks, but when we get in that room, it’s a lovely warm room to work in, musically.

“You hear Mick pick up the harmonica or something and Charlie joins in with the thunderstorm. Even though it doesn’t look like he’s even touching the drums, it sounds like a firework display, still. Keith and I are rocking, and Darryl Jones and Chuck Leavell are absolute magic.

“So the whole thing is just earthy, and very sparse, as shows in the Doom And Gloom and One More Shot records. There’s some kind of simplicity in the magic of keeping it raw, not overdoing it too much and not trying to get too technical or airy-fairy and over-indulgent about the whole thing. Mick is writing up to an incredible standard with his words. We’re just trying to do what we do, earthy music.”

If One More Shot is a spirited late-period Stones entry, Doom And Gloom can make a strong claim to be a latter-day classic, with reviews to match.

“Doom And Gloom was quite new, just a few months old,” says Jagger. “I did it with Matt Clifford, who I often do demos with, he does the programming and I do guitars… and singing, of course. So it was kind of

good that it was fresh, it wasn’t something that I had to dig up out of the sack.

“I worked on it with Don Was and Jeff Bhasker, you know Jeff? He’s done a lot of rap records. I sent tunes to Don and Jeff, and I was going ‘This is the one, you’re going to love this one,’ and they’d go, ‘Yes, it’s very nice, Mick. Got any more?’ So I’d send another one. ‘Well, maybe we should do this in another way.’

“So I sent them Doom And Gloom and they went ‘Wow, this is great.’ I said, ‘Okay, I thought that was a bit obvious, but there you go.’ Then they started working on it, and it didn’t come out, to be honest, a million miles away from the demo. The form of it, and the sound, is very similar, so it ended up sort of a deluxe version of how I’d done the demo. Which is the way it should be, really.”

By Keith’s own description, 50 years on the road can be “a pretty dark area” and when you look at the new Crossfire Hurricane movie, with its extended footage of the drugs, deaths and disasters of the band’s first decade, you remember exactly how dark. But the 50th anniversary is also a chance to go back to a more naive time, one that Charlie Watts remembers before he was even in the Stones.

“Bill and I joined on January 2, ’63, I think it was. He’s adamant about that,” says Charlie. “I remember the Marquee gig on July 12 because Alexis Korner’s band, of which I was the drummer, did a radio broadcast, and I remember coming from Broadcasting House and going down the back stairs, or side actually, to the Marquee, and standing in the doorway looking at Brian [Jones] doing his Elmore James stuff with the slide.”

Aficionados won’t be surprised to know that every song in the Stones’ 18-track set list that historic night was a cover. What might be more surprising is that, among the numbers you’d expect such as Chuck Berry’s Back In The USA, Leroy Carr’s Blues Before Sunrise and no fewer than six Jimmy Reed numbers, they did one by teen heartthrob Paul Anka, and not even a recent hit, 1957’s Tell Me That You Love Me.

“I’d played with Mick a few times with Alexis, because Alexis never had a [regular] singer,” Charlie recalls. “He had Ronnie Jones, an American guy, and Paul Jones sang with Alexis then, and Mick did a few gigs. Keith sat in with us at Ealing, I remember that, and Brian and I played a few times. I used to play with a few bands, as well, like Art Wood’s band.”

Can Watts remember the first time he saw Jagger sing live? “The time I must have really been impressed was when we used to do the Crawdaddy, when it moved from the pub [the Station Hotel, in Richmond]. This is looking back, so I could be completely wrong, but we moved from the pub to the athletic thing [Richmond Athletic Ground].” His memory is admirably intact.

“I can remember Mick dancing in there, and we got used to it, we used to play every Sunday. We used to play at Ken Colyer’s club opposite Leicester Square tube station, and we’d go from there to the Athletic Club. They were our two gigs that kept us going, actually, for a while. But we always got more and more people. We’re very fortunate like that.”

Even in the enormodome tours of recent decades, there have always been clues strewn about the stage that the Stones remember and respect their blues roots. Or, to be more accurate, on the B-stage, the small set that first popped up, as if by magic, in the middle of stadia around the world on the Bridges To Babylon tour of 1997. Fans who previously had a pretty average view of the massive stage suddenly found, to their amazement, they were almost within touching distance of the Stones, as they turned back into the rhythm and blues unit of their youth to perform songs such as Little Red Rooster, I Just Want To Make Love To You and Little Queenie.

“We always carry a little bit of Chuck Berry with us,” says Wood, with some inside information about the recent rehearsals that saw them work up about 80 songs inside a month. “It’s good to have ‘new’ old stuff too.”

“Did Mick tell you that we’re doing I Wanna Be Your Man? The Lennon-McCartney song, that’s a very important piece of Stones history, and Beatle connection. John and Paul actually approached them in Wardour Street.

“They were at different points in the street, and they said, ‘Oh, we hear Mick and Keith are up the road, get ’em down, we’ve got a song for ‘em,’ and they both went ‘Oh, we hear you’ve got a song for us?’ ‘Yeah, it goes like this, do-do-do-do, I wanna be your lover baby…’ but it was great, and they both recorded it.

“It’s brilliant, and I get to play slide on it. I love all the tools of the pedal steel, and the slide and lap steel. I’ve got a new Les Paul, I’ve never been a Les Paul man, but I’m playing that more and more now, combined with my Fender Strats and all that.”

- Q&A: Keith Richards

- Ronnie Wood: Diary Of A Mod Man

- Top 10 Exhibits At The Rolling Stones Exhibition

- The Rolling Stones Quiz

I Wanna Be Your Man became the Stones’ second hit late in 1963, in the first example of how the two soon-to-be-superstar groups scratched each other’s backs. John and Paul gave them the track as a single, which climbed to number 12, then released their own version, with Ringo’s customarily approximate vocal style, just three weeks later on the Fab Four’s second album, With The Beatles.

“When I was a fan of the group in college, the Stones were known for Route 66 and everything, in those early Eel Pie Island days,” says Wood. “I think that’s got to be logged, paid tribute to and seen as part of the big picture.”

Richards laughs when I playfully suggest they should go all the way back and play their first single, Chuck Berry’s Come On, which soon came to sound almost painfully innocent as they honed their skills.

“I think we’ll leave that one,” he laughed, making fun of its choppy, awkward rhythm.

When I ask Ronnie if any other early Stones tracks re-emerged in the Paris rehearsals, another one pops out, to my surprise. “Yeah, Tell Me!” He taps his foot excitedly. “All kinds of songs, Not Fade Away… very important links in the 50 years.”

Tell Me is indeed an important, if unsophisticated, milestone as the only Jagger-Richards composition on the band’s self-titled UK debut album of April 1964. It was also the first Mick and Keith song to become a US single.

The long-lost film Charlie Is My Darling, made during the Stones’ Irish tour of 1965 and newly reactivated, in includes some fascinating backstage footage of Mick and Keith on the cusp of establishing their songwriting telepathy. We see them working up Sittin’ On A Fence, which they would then “donate” just as The Beatles had done to them, giving it to the British duo Twice As Much, who took it into the UK top 30. The connection was that the group were signed to Immediate, the label launched in 1965 by the Stones’ co-manager Andrew Loog Oldham and his business partner Tony Calder.

“Look what happened to the bands that didn’t write their own songs,” Oldham said recently. “I mean, you’re like a plane without parachutes. It’s a voice. It’s a very necessary part of a band to have a voice. Or else you’re just duplications.”

But in the days before the voice became audible, the Stones were in thrall to any number of American bluesmen and early rock‘n’rollers, and they never lost the affinity. To this day, one of the greatest achievements of the group’s early years, perhaps even all 50 of them, arrived in 1964 when they cut Willie Dixon’s Red Rooster.

“It’s the only blues record to make number one,” says Watts, “which I never knew, but Bill Wyman said it, and it is amazing when you think about it. I don’t know how many blues records I play and love, and they’re nothing in chart terms.”

Berry’s influence, too, was immense.

“I mean, he’s the Shakespeare of rock‘n’roll,” Richards told me a couple of years ago, when I visited his home in Connecticut just before Life was published. “It was rock‘n’roll poetry. I mean, School Days, Too Much Monkey Business, and the subject matter coming out from every different angle. Memphis, Tennessee itself, beautiful record. I admired the man so much. It was just a bit of a disappointment for me to find out he was human.”

How Richards came to be Berry’s musical director for the 1987 film Hail! Hail! Rock‘N’Roll is a hair-raising story for another day, but the wider point is about how the Stones’ original heroes are still giants in their eyes, and how certain early blues and R&B numbers have underpinned their working lives.

Route 66 is one such number, fit for interpretation as the group did in the 1960s, right up to recent live revivals and even an interpretation by Watts last year on his splendid live album with his ABC&D Of Boogie-Woogie outfit.

“Ah, Bobby Troup [songwriter of Route 66],” glows Charlie. “It’s difficult to say how you do it differently with a jazz group. What you play fits those particular set of players. The Stones one was Chuck Berry guitar-based, with Stu [road manager Ian Stewart] trilling over the top, or rumbling underneath. The jazz one is piano-based, with a swinging bass, which gives a different feel. Sometimes when we get Jerry Lee Lewis or Little Richard-ish, I’ll play like I would with the Stones.”

But it’s not just those American greats from the Stones’ early years that continue to inform what they do. It’s touching to see how these multi-millionaire rock superstars still doff their cap to Stu, the man who did more than any other musician to orchestrate their early rise. Even if he did affectionately refer to the group as “my little shower of shit”.

The extended band of the 21st century should get far more credit, Richards says, and sees a direct link back to their 1960s origins. “I want to give Mr Darryl Jones his due here, and Mr Chuck Leavell. After all, we used to have Ian Stewart, and he went many years ago [27, to be exact]. But before Ian died he said, ‘If anything should happen to me, Chuck’s the man.’ And we still work for Stu, and Chuck’s been with us for years and years now.

“Darryl is an incredible bass player. He and Charlie together lock in, and to me the most important thing is a rhythm section. Darryl and Chuck very rarely get mentioned, because the focus is on the Stones, these four white British guys… for whatever reason, marketing or whatever. But it’s necessary to mention these two cats, they’re just as important as the rest of us.”

Just as Richards says the band still play for Stu, Wood emphasises the creative presence of his forebears.

“As a guitar player, I still respect what Brian Jones and Mick Taylor did, and I try to echo to this day what they contributed,” he says. “It’s great to have Mick around, I’ve played with him recently a few times.

“He’s an absolute magician with the guitar, and I still learn a bit from our exchanges, and he’s always learning from me, too. It’s a great rapport, and Keith has a lot of respect for him in the whole realm of guitar players, such as Eric Clapton, who we may ask up as a guest during the 02 gigs, and maybe Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, whatever. But we just love to keep that fellowship going, and it’s great to see the respect between Darryl Jones and Bill Wyman.

“It’s been five years since we last played, at the 02, funnily enough, and those gigs we did there were so incredible, we didn’t want the tour to end. We left on a high, wanting more. Now, I see the band’s chemistry is stronger than ever, and we’re still willing to learn and aim high, learning and re-learning. Looking at songs differently, and in my case in a really focused way, focused like I’ve never been before.”

Whether or not we’re starting on the last chapter of a mighty volume, the important thing is that it’s a new chapter. Wood and Richards, at least, think the recaptured spirit could lead to more shows and recording next year but, for now, Keith is raring to hit the stage again.

“It could just be my version of butterflies, but I don’t feel queasy about it, it’s like, ‘Open the cage and let the bugger out,’” he says. “I have no fear of that at all. My idea at the beginning was that, oh God, we’re going to have to knock off a load of rust, then we’re going to have to go to the oiling. But I was totally wrong.

“I love playing with Charlie, that’s my panacea for everything. Once I’ve got him there and we’re playing together, we just give each other a look. ‘Yeah, yeah, this is the band and this is great stuff.’ And you want to pass it on.

“We wouldn’t do this if people didn’t want it,” he concludes. “I was amazed when the London and New York shows sold out, millions of people. I’ve been at home with the kids, walking the dog but there’s something inside going ‘I’ve got to get this thing together.’”