"I was driving, Steven Tyler had a gun and we were on some mission": The scandalous story of Alice Cooper's Billion Dollar Babies

The Alice Cooper Band's outrageous behaviour prompted a statement in Parliament while their songs thrilled a generation

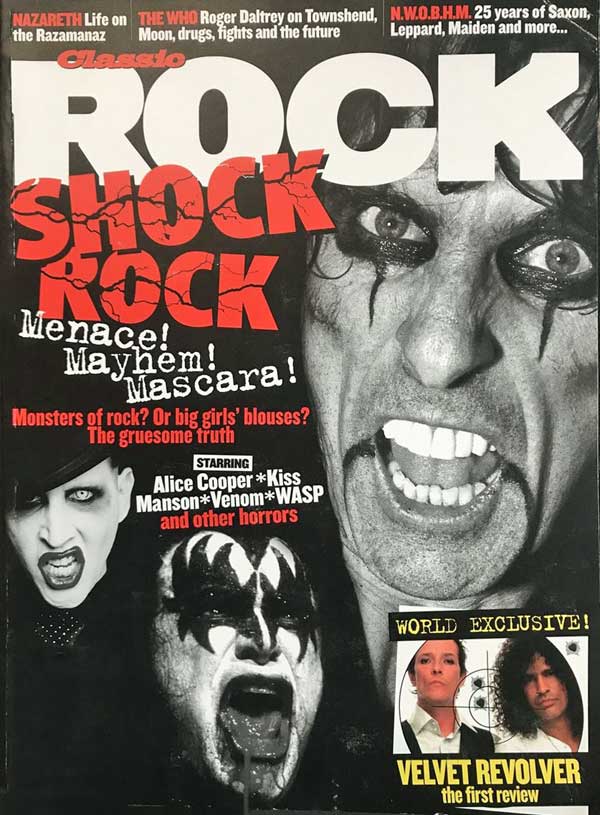

Forget Marilyn Manson, forget the Sex Pistols; when it came to shocking the self-appointed guardians of international morality to the core, Alice Cooper pretty much wrote the handbook.

Flaunting a sketchy past swathed in urban legend and cunningly fabricated falsehoods concerning witches, ouija boards, dismembered chickens, blurred genders and necrophilia, Alice Cooper succeeded in outraging the forces of decency to an unprecedented degree over the course of his casual early-70s transition from cult notoriety to mainstream ubiquity.

Cooper’s infamy was such that in May 1973 Leo Abse, the incumbent Labour MP for Pontypool, spluttered in the House of Commons: “I regard his [Cooper’s] act as an incitement to infanticide for his sub-teenage audience. He is deliberately trying to involve these kids in sado-masochism. He is peddling the culture of the concentration camp. Pop is one thing, anthems of necrophilia are another.”

The nation’s leading censorial nanny figure, Mary Whitehouse, head of the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, offered eager support to Abse’s campaign to ban Alice Cooper from returning to the UK. But as public reaction veered in the general direction of hysteria, sales of Billion Dollar Babies (Cooper’s most provocative recording to date) soared stratospherically; then, as now, controversy sells, and in 1973 nobody was selling more than Alice Cooper.

Of course, back in those days Alice Cooper were a band; five individuals who had translated a shared fascination for the mop-tops and the macabre into a million-dollar industry that had not only brought them universal vilification as depraved, corruptive pariahs, but also celebrity beyond their wildest dreams.

The quintet’s story begins innocently enough in Phoenix, Arizona, when track athlete Vincent Furnier is volunteered to organise the Cortez High School’s autumn 1964 Letterman Talent Show.

Unfortunately, no one seems to boast any discernible talent, so Vince encourages some friends to take the stage as The Earwigs where they mime along to Beatles records while wearing Beatles wigs. Guitarist Glen Buxton can actually play his instrument. And while drummer John Speer fumbles his way around the rudiments of percussion, bassist Dennis Dunaway hones his craft with the benefit of some valuable lessons from Glen.

The Earwigs metamorphose into The Spiders; they play local Battle Of The Bands shows; and they replace their departing rhythm guitarist John Tatum with ex-Cortez High football star Michael Bruce of The Trolls.

Following a move to LA in spring ’67, the fledgling Coopers, now known as The Nazz (but not for long, thanks to Todd Rundgren’s band of the same name), replace John Speer with fellow Phoenix émigré Neal Smith and set about endearing themselves to the Sunset Strip in-crowd by hosting regular séances.

Soon enough – now that they’re mixing in a social circle that includes The Doors’ Jim Morrison and Love’s Arthur Lee – Miss Christine (of The GTOs: Girls Together Outrageously, the world’s first all-female rock band) arranges for the band to audition for Frank Zappa’s Straight label. The somewhat over-eager Coopers famously turn up for their 6.30pm appointment at 6.30am, but find their naïve tenacity amply rewarded when Zappa offers them a record deal.

Two days after changing their name to Alice Cooper they are taken on as the house support band at the 20,000-capacity Cheetah Ballroom, where they gradually build a following in spite of the fact that their vocalist – having ditched the name Vince in favour of the infinitely more noteworthy Alice – had taken to wearing full make-up and a pink clown costume.

Gradually, the winning Alice Cooper formula takes shape, and after recording a brace of feet-finding collections on Zappa’s Straight imprint (1969’s Pretties For You and ’70’s Easy Action) the band sign to Warner Brothers and, with Canadian whiz-kid producer Bob Ezrin at the controls, hit the peak of their form with three set-piece collections released in rapid succession: June ’71’s Love It To Death (the album that shocked America), December ’71’s Killer (the album that conquered America) and July ’72’s School’s Out (the album that conquered the world).

School’s Out, bolstered by the enormity of its anthemic title track, quickly attained the accolade of being the biggest-selling album in Warners’ history and, thanks to a frenzied tabloid press virtually foaming at the mouth with a level of hyperbolic vitriol unseen since the advent of the Rolling Stones, Alice Cooper became the most newsworthy and controversial band on the planet. But now came the difficult bit.

In the face of blanket condemnation from the great, the good, the humourless, the pious and the post-pubescent, the band needed to consolidate their position. Specifically, they needed to make the greatest album of their career: an over-inflated Grand Guignol masterpiece; an ostentatiously offensive, flashy, crass and unbelievably expensive combination of Herschell Gordon Lewis and Busby Berkeley positively guaranteed to expand the generation gap to Grand Canyon proportions.

In short, they needed to make Billion Dollar Babies. Following School’s Out was always going to be a daunting task, but with band morale at an all-time high no one involved harboured a shred of doubt that they could not only do it, but also do it in style

“I knew we had a great team,” Alice remembers today, “and when you’re that age you think you’re indestructible. I don’t think we really conceived of how big School’s Out was. We were really flying by the seat of our pants back then. You’d do two albums a year in those days, and two world tours to go with them. But, again, we considered ourselves indestructible, so we didn’t feel pressure at all.” “

We had other people doing the doubting for us,” Dennis Dunaway smiles. “It was us against the world, basically. Even after we were successful and surrounded by people telling us how great we were, there were always plenty more ready to share their opinion that we weren’t.”

Reflecting the dogged buoyancy and inner confidence that kept their spirits high in the face of blanket media condemnation – and also in the grand show business tradition of ‘if you’ve got it, flaunt it’ – the band elected to celebrate their newly elevated status in the album’s title itself.

"The Billion Dollar Babies concept was simply making fun of ourselves,” Alice Cooper says in retrospect. “Here was a band nobody would touch three years ago, and now we’re the biggest band in the world. We’d look at each other and go: ‘We’re like billion dollar babies’."

“We were getting voted best band in the world over Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles. We’d look at that and laugh. I almost called up McCartney and said: ‘Listen, we didn’t vote on this’. Led Zeppelin we would give a run for, but when it came to The Beatles and the Stones we were embarrassed to be ahead of them in anything.

“Billion Dollar Babies was our most decadent album. It was reflecting the decadence of a time when we were living from limousine to penthouse to the finest of everything including… well, the finest of everything. We couldn’t believe people were actually paying us to do this. We would have done it for free, because we were just a garage band who happened to be at the right place at the right time.”

Despite gigging themselves to a virtual standstill, appearing in every print publication in existence and working on a movie project titled Good To See You Again Alice Cooper (finally released in 2005 through Rhino Home Video), the band were still on a creative high and writing songs of exceptional quality.

“We’d been writing pretty much constantly since Easy Action,” Michael Bruce recalls. “So by this point we had really started to come into our own. We were on an upward spiral.”

And with this confidence came a desire to push the envelope even further into the arena of the bizarre.

“Dennis Dunaway had a lot to do with the insanity of the band,” Alice admits. “I let Dennis be as surreal as he wanted to be. He and I were both artists in school and were both really into Salvador Dali. Also, Dennis did a lot more… let’s just say experimental stuff, than I did.”

We were getting voted best band in the world over Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles

Alice

“I was always the crusader for the avant-garde,” Dunaway agrees. “Anything that we would come up with that sounded like anyone else, I was always there to change it. So the songs would always be under attack from me if they didn’t sound unusual enough.”

Making sure that the Coopers’ collective vision was realised in the recording studio (no matter how unusual it became) was a man generally regarded to be the band’s sixth member, producer Bob Ezrin, who had helped to hone the Alice Cooper sound since Love It To Death.

“It was like two trees growing next to each other.” Alice explains. “Bob Ezrin was ready to produce a band, and we were ready to get a producer. He was a young guy with a theatrical background, and we were a rock’n’roll band that wanted to be theatrical. Bob Ezrin was our George Martin.”

“I don’t want to underestimate how important Bob was,” Neal Smith cautions, “but I don’t want to overestimate it either. In getting our sound on record Bob was hugely important, but Billion Dollar Babies was a team effort. His biggest achievement, I think, was helping create Alice’s character. Because between Easy Action and Love It To Death a character evolves vocally that pretty much solidifies into the real Alice Cooper, and Bob had a lot to do with that.”

“Bob definitely came along at the right time,” Dunaway says. “Mike Bruce’s songwriting had improved leaps and bounds, Neal and I had improved across the board, and Alice’s voice had matured – gotten much stronger and less nasal than the early days – but when Bob came along we were still trying to fit a million ideas into each song. It took him to come in and say: ‘No, this isn’t a song, this is a whole album’ to finally focus our direction.”

The Billion Dollar Babies album was recorded in three stages. Initially a mobile studio from New York’s Record Plant was parked up outside The Cooper Mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut, and the basic backing tracks were laid down. After a couple of months of furtive recording in between their myriad other commitments, the band flew to London’s Morgan Studios to record overdubs and vocals, then returned to the Record Plant for mixing.

Unsurprisingly, given the band’s penchant for partying and their choice of friends, the Morgan Studio sessions in London soon played host to drunken, after-hours jams featuring some of the greatest – and indeed the most indulgent – stars of the day.

“We had access to a lot of the stars here,” Alice remembers “In fact T.Rex, Donovan, Harry Nilsson, Ringo Starr and Keith Moon are all on that album somewhere, but none of us know where because the session was so drunk.”

“Keith Moon would come down with Marc Bolan,” Neal Smith recalls. “In fact Alice, me, Keith and Marc were sitting at a table one time when Marc kept on pushing at Keith to be in a band with him, which was so funny because I couldn’t imagine a worse combination of two musicians.”

“Harry Nilsson had a really negative effect on the session,” Dunaway says. “We could have got a lot of great things out of that group of individuals jam-wise, or even for use on the album, if Harry Nilsson hadn’t been there, falling drunk on to the mixing board and wrecking it up. The guy could hardly walk, but he’d sit down at he piano and out would come this beautiful voice and beautiful melody. Jeez, I never figured how he could do that.”

Also present at the Morgan sessions were a pair of session guitarist colleagues of Bob Ezrin: Dick Wagner and Steve Hunter who, unknown to many contemporary fans, were often called in to cover for an increasingly ailing and erratic Glen Buxton.

“Hunter and Wagner were definitely on the album,” Alice says. “And we wanted everybody to know it. We weren’t going to pretend like Glen was playing everything, and be phoney about it, so we gave them a credit. Later on I used them exclusively for Welcome To My Nightmare.”

“We knew Dick from Michigan,” Michael Bruce says. “There were always musicians that were better than us in every studio we went. Having him and Steve on the album wasn’t seen as some dark portent of things to come, they were just incredible players. If a library doesn’t have the book you want, you just go to another library. We’d already used Dick on School’s Out and Under My Wheels.”

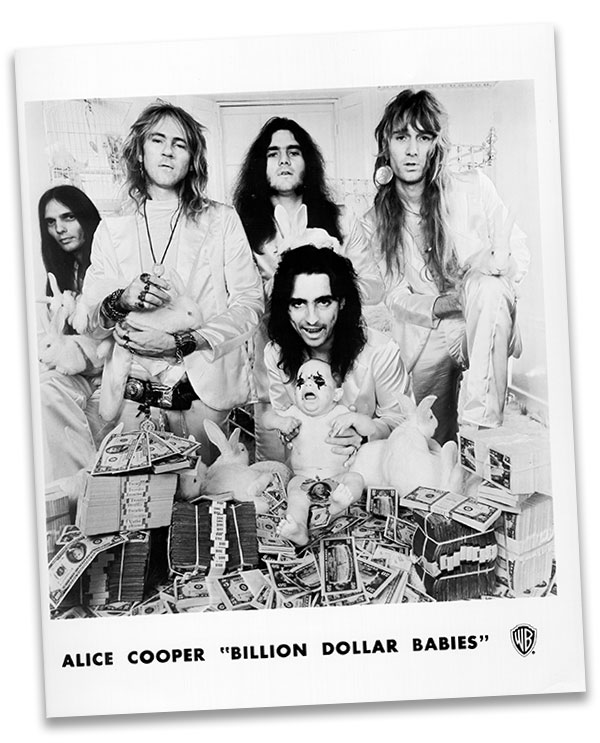

While in London the band were photographed by David Bailey for the inner sleeve of Billion Dollar Babies. It presented yet another golden opportunity to gleefully taunt their legion of apoplectic detractors, and the band rose manfully to the challenge.

Dressed in diaphanous white silk and surrounded by literally stacks of cash, the musicians casually caress albino bunny rabbits, as their singer presents to the camera a live human baby which is naked except for a splattering of trademark Alice Cooper eye make-up.

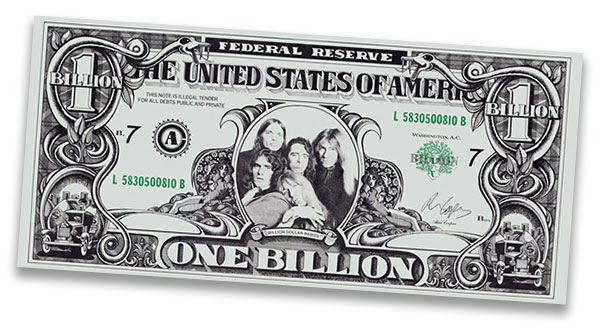

“Any chance we got to exaggerate anything, we did it,” Alice says when considering the revolutionary cover design of Billion Dollar Babies. “We made a giant, billionaire’s wallet, and inside it there was a billion-dollar bill: very American; everything big and expensive. And we used the best photographer, the guy we were sure was the guy in Blow Up, because we thought there was going to be models laying naked around the place… and there were a few.

“We brought in a million dollars of real money from Brinks. What you didn’t see in that picture were the two guys with machine-guns who were guarding the money. Everything we did was overblown and the British audience loved it. They loved this big American band that the MPs just hated. The fact we were flaunting it was even better, because we suffered so much at the hands of the press.”

“That cover shoot is actually a recreation of one we did for Love It To Death,” Dunaway points out. “We brought a photographer into the farm we had in Pontiac, set up a brass bed in the living room and posed with some white rabbits that my wife Cindy had. Of course, we didn’t have the million dollars then. In fact the reason those shots never got used was because we couldn’t even afford to pay the photographer’s bill.”

Directly prior to the release of Billion Dollar Babies, a promotional flexi-disc single was given away with the February 17 issue of the New Musical Express. The B-side was short excerpts from the album, while the A-side boasted the exclusive track Slick Black Limousine.

“That was one of the few songs we had laying around,” Neal Smith explains. “It was supposed to be an Elvis Presley, rock’n’roll kind of thing, but in the end it got more Alice Cooper-ish, with rolling drums and dark psychedelics.”

Finally released in March 1973, Billion Dollar Babies, despite being critically crucified for its apparently unprecedented lack of taste, entered the UK chart at No.1. Within days, and with the band already out on the road promoting it to the hilt with their soon-to-be record-breaking Billion Dollar Babies Show, the album had replicated that chart-topping achievement in the USA.

By now the press were in meltdown. Just four days into the tour Melody Maker announced that Alice had been killed due to a fatal malfunction during his I Love The Dead guillotine finale. Almost as soon as this story was eventually adjudged to be false, yet another urban myth had arrived to take its place around water coolers the world over: apparently the baby in the B$B cover shot had been rendered blind by incautiously applied eye make-up. (But before you all rush to tell your friends, obviously it hadn’t.)

The Billion Dollar Babies Show may have been the largest-grossing rock tour in the history of mankind, but it was also one of the most gruelling. Flying from city to city for months on end is one thing, but being beheaded twice a night is something else again.

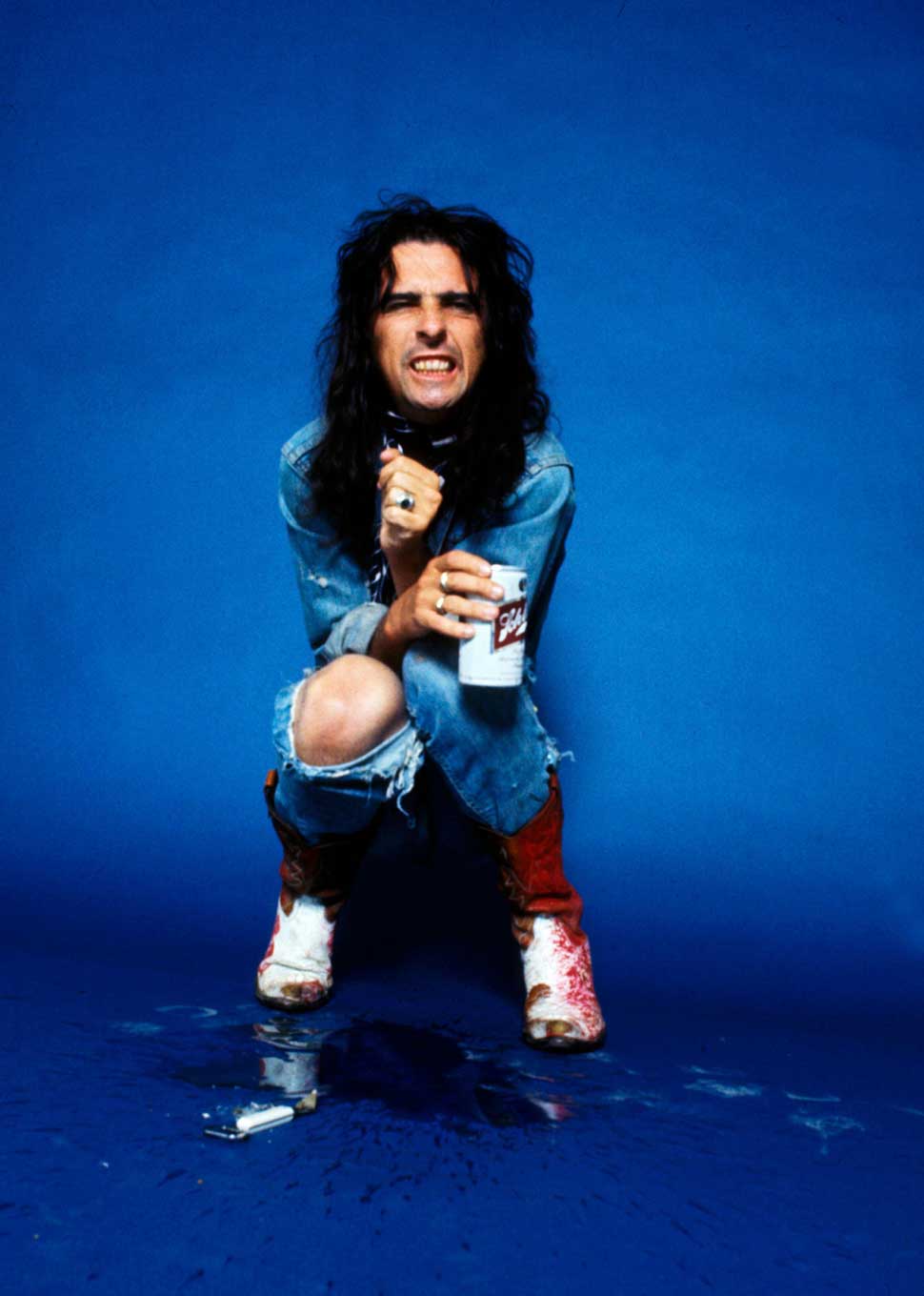

“Again, you’re indestructible,” Alice explains. “When you’re selling out six nights a week and every night there’s 15,000 people out there you feel no pain. But underneath I was eroding. You couldn’t tell by the stage show, you couldn’t tell by my personality, but every night the alcohol became a little bit more like medicine and a little less like fun.

“By the time I was doing …Nightmare I was ready to die, go into hospital or have a nervous breakdown. There came a point where every time I saw my costume I would almost start crying and almost throw up.”

“The Billion Dollar Babies tour was horrendous the way that it ended up,” Mike Bruce grimaces. “It was supposed to be sixty dates in ninety days, but I think it ended up at almost eighty.”

“You’re pushing yourself on exhaustion,” Dunaway adds. ”You’d be lucky to get to bed by four in the morning, then you’d have to get up to catch an early flight or drive to the next city. But Alice and I were long-distance runners – that’s how we met – so we had this keep-going-at-all-costs mentality that pulled us through some situations where a lot of other bands would have given up.”

“It was gruelling,” Smith concludes, “but it wasn’t unbearable… This band lived for the road."

And, of course, road-life did have its moments: “The groupie scene was beyond anything you can imagine,” Alice leers. “Go backstage now – if you want to see a bunch of fat guys move amps. But back in the seventies if you went on tour with Rod Stewart and The Faces you’d see anything. It was the golden age of decadence.”

Of course, over the years Alice Cooper has ceased to be perceived as a band at all, and is now popularly considered to be an on-stage persona adopted by the artist formerly known as Vince Furnier – a kind of evil Dame Edna, if you will; a Mister Hyde-styled alter ego so immensely dominant that it’s all too easy to forget that Vince’s golf-loving Doctor Jekyll even exists. Until he chums up to Ronnie Corbett on TV, that is.

Yet although the former Furnier retains exclusive custody of the lucrative Cooper brand – and legitimately so, as it was he alone who initially coined the moniker – the actual development of the finer points of the Alice Cooper character was very much a team effort.

“Alice came up with the name,” Dunaway says, “and I thought it was a genius idea. It shocked me when he first suggested it, but when I ran it by my parents and saw their mouths drop open I knew it was the name for us.

“The name did belong to the band, but we didn’t want people to know that we’d helped Alice develop the character. However, the make-up was my idea, the snake Neal’s idea, and the executions were band ideas.

“The Alice character was born of necessity; in the early days of Pretties For You Alice was shy. He had a temporary case of stage fright, where he’d stand with his back to the audience for the whole set, and we weren’t sure what to do about it. Then at one rehearsal, when the band was still starving in California, I suggested that he develop a different character for each song, because he didn’t have a problem when he was on stage being Keith Relf or Mick Jagger, it was only when we started doing original material he was at a loss as to who he was and what he wanted to project.

“So during Nobody Likes Me he was a lonesome guy singing through a window; for Levity Ball a kind of Gloria Swanson, Sunset Boulevard character that developed into a strong part of the Alice Cooper persona. We had a song called Fields Of Regret that had this sort of dirge-like sermon in the middle that I think was influenced by Alice’s father being a minister, but Alice became this darker, more sinister character for that particular song. And people loved it, so I said: ‘We should write more songs that have that character in them’. It didn’t happen overnight, but by the time we got to ‘Love It To Death’ that concept of the Alice character had really taken root.”

Alice, meanwhile, has rationalised his need to attain Cooper-ism thus: “Alice came out because there were all these Peter Pans and no Captain Hook.”

He also admits to having based Alice’s singular sense of style on Anita Pallenberg’s sadistically seductive Black Queen character from Roger Vadim’s classic cult fantasy Barbarella: “I saw the Black Queen and went: ‘That’s Alice right there’. Black gloves with switchblades at the end, black make-up, with the eyepatch over her eye… that is so good. Then I’d see something else in a comic book. And as I stitched all these characters together, pretty soon there he was.”

Somewhat surprisingly, Alice Cooper were never really perceived as a drug band. “We were way too American for that,” Alice insists. “Too mid-West and too wholesome. We drank, watched football, baseball and horror movies, called our moms, had Thanksgiving dinner and were the most all-American, homespun guys you had ever seen in your life. All on the track team, cross-country team, lettermen, we were just as wholesome as you could get. Church on Sunday…”

Okay, enough already. But is Alice’s memory entirely reliable?

“Put it this way,” Neal Smith says: “Alice is the one who went through rehab. I tried everything that was ever around in those days. Michael, Dennis, Glen and I all did. You didn’t have to buy it, anywhere we went it was always there. But I never liked anything as much as drinking beer, and we probably consumed more alcohol than any other band on the planet.”

Alice had started drinking in Los Angeles and had drunk constantly ever since. He and Glen Buxton would routinely split a case of beer a day, and Alice would never take to the stage with less than a six-pack inside of him. But, as luck would have it, he was an uncommonly ‘functional’ drinker.

“I could get up, drink beer all day, but when it came to interviews I would never slur a word and when it came time to do TV I knew every line.”

“Alice was a real professional drunk,” Mike Bruce agrees. “He was always where he was needed to be, and never complained. So it was a bit of a shock to me when he spoke of his alcoholism. I mean, he was always really thin and ghastly looking, so it didn’t really sink in.”

But while Alice had his drinking under some degree of control, the same could not be said for his drinking partner. “Everybody was worried about Glen,” Alice has said, “because Glen was just not progressing. Everybody seemed to be getting better at what they were doing and Glen just wanted to have his drink, his cigarette and just kind of float.”

Shortly before the Billion Dollar Babies tour, Glen Buxton’s alcoholic overindulgence caused his pancreas to ‘explode’. And following life-saving emergency surgery the guitarist returned to the Cooper Mansion in Connecticut to recuperate. With regular substitute Dick Wagner unavailable guitarist Mick Mashbir and keyboard player Bob Dolan were brought in to paste over gaping cracks in the band’s live sound.

As has already been established, the battery-recharging sabbaticals enjoyed by today’s major stars were simply not an option in the 1970s, and consequently the seriously debilitated Alice Cooper soon found themselves back on the recording treadmill. On this occasion, however, not only was Buxton’s contribution seriously below par, but Bob Ezrin – who had already committed to producing Lou Reed’s Berlin – was also out of the equation.

As a result, Muscle Of Love, the eagerly awaited follow-up to Billion Dollar Babies – was a commercial, as well as creative, catastrophe. That’s relatively speaking, of course – it still succeeded in shifting 800,000 copies. But the band should have been prepared for the worst – they had been warned.

“Bob Ezrin heard the songs and went: ‘Guys, this isn’t up to par’,” Alice admits. “But we were swimming in popularity at that point, we could do no wrong. So it was a perfect example of a band being over-confident. The songs were okay, but put them all together and it didn’t work.”

“We simply wanted to do an album of great songs,” Neal Smith shrugs. “We’d also heard that there was a new James Bond movie coming up, so we wrote The Man With The Golden Gun specifically for that (the band’s contribution was ultimately passed over in favour of Lulu). The major difference with Muscle Of Love was that as it wasn’t a concept album, we didn’t have a show based around it. The previous four had all come complete with an accompanying stage show. I guess we just couldn’t figure out another way to kill Alice.”

“Glen’s problems took priority,” Dunaway adds, “so we weren’t able to work on songs as we had before. We had different musicians coming in, and the whole album sounded much more safe because Bob Ezrin wasn’t there. He’d always been very tolerant of my interest in pushing the avant garde, but that’s not really Jack Richardson’s style.”

“As a producer, Jack Richardson was about as close as you could get to a Bob Ezrin,” Mike Bruce offers. “He also came from Nimbus 9 Productions in Canada, and had even engineered a couple of our previous albums alongside Bob Ezrin. So it wasn’t as much a matter of what went wrong with ‘Muscle Of Love’ as what didn’t go right.

“We’d insisted on packaging it in a cardboard carton; that was another problem. When we toured it there was a truckers’ strike, so we couldn’t use our normal stage set; we would often just turn up and play.”

With their lead guitarist plummeting into oblivion and their sales figures apparently embarking on a similar course, the Alice Cooper group decided to take a year-long hiatus that has so far lasted for three decades. At least that’s how three of them see it.

“The guys were tired of spending all the money on the show,” Alice says. “I understand that, but it’s what got us there. And they wanted to wear Levi’s. So I said: ‘If that happens I can’t be part of it. I can’t be the lead singer in Creedence Clearwater here’.

“In the end everybody wanted to do their own album. So I went: ‘If that’s going to happen, I’ve got to let you know right now that I’m going to take every penny that I have and invest it in the next album [which was Welcome To My Nightmare]. If you thought Billion Dollar Babies was the biggest thing you have ever seen, I want this to be bigger’.

"So, worried about having to watch all of their money go down the drain, they said: ‘You’re on your own’. So I said: ‘Okay. No hard feelings’. At least we knew where everybody stood. Nobody argued, nobody yelled, everybody just went, okay.

“So they all did their albums, and I took Bob Ezrin, our manager Shep Gordon and said: ‘Let’s roll the dice. We’re either going to be totally broke after this or we’re going to be really, really big’. And that’s when I started writing …Nightmare with Dick Wagner.”

“Well it’s not true,” Dunaway insists. “Mike, Neal and I did the ‘Battle Axe’ show [billing themselves as The Billion Dollar Babies] after that, and I think spent more on that than we had on the previous Alice Cooper tour. So no, that wasn’t the reason at all. I also hate that spin about how we refused to wear stage costumes. I mean, who would believe that? Just walking down the street we looked more outrageous than most bands.

“I didn’t like the idea of bringing in schooled dancers. I thought it would make the show too slick and take away the raw edge that was our power. Neither did I like the idea of big, fluffy monsters; I wanted something more gritty – the chopped-up mannequin approach.”

“Well, Alice says that stuff,” Mike Bruce says, “and it’s like he believes it so much that it’s become his reality. But no, it wasn’t that the band didn’t want a stage show, we just wanted to tone it down a little, make it into a funkier, West Side Story kind of thing as opposed to a big, lavish, Billion Dollar Broadway Babes type of thing. We had also been touring to the point where we needed to back off on the throttle and let momentum carry us. The road had taken its toll: physically speaking, our cheques were cashed and the bank was notified.”

“We had come back from Europe,” Neal Smith says. “And because Michael had some material that he wanted to record himself, we all decided to take a year off to do our various solo projects. Michael did In My Own Way, I did Platinum God and Alice did Welcome To My Nightmare. Alice found success on his own with …Nightmare and, what with the continuing Glen situation, we never got back together again.”

And have the former Billion Dollar Babies been left harbouring regrets? Well, as you might expect, some more than others.

“I certainly would’ve loved to have continued with the band,” Smith admits. “I wish that after we’d done our solo projects we’d have honoured what we’d stated and gotten back together to record the ninth Alice Cooper album. And who knows, maybe we will one day.”

“If I had to do it over again,” Bruce reflects, “I’d probably try to keep it going longer than it did.”

“I just wish we’d recorded more,” Dunaway says, laughing. “We never had a tape recorder, and as a result we lost a lot of really good songs simply by forgetting how they went.”

“I wish I’d seen a bit more of those days sober,” Alice confesses, “so I could remember more. Every once in a while I’ll get a flashback – like, because that’s all I can remember: I was driving, Steven Tyler had a gun and we were on some mission. We ended up at my house, but all I remember is a Rolls-Royce, Tyler, a gun and a lot of alcohol. Did we shoot someone and bury them? I have no idea.”

Ironically, while Glen Buxton's premature death from pneumonia in October ’97 effectively rendered a fully-fledged Alice Cooper reunion impossible, it may well have made it easier for the four surviving members to finally regroup. After all, the band was as much Glen Buxton’s as it was anybody’s, and while he was not in any condition to tour, for his bandmates to have reunited without him would have been simply unthinkable.

But now that their former sparring partner has finally been laid to rest arguably there’s really no obstacle to the quartet sharing the same stage once more. In fact they’ve already done so: at Alice’s Cooper’stown restaurant in Phoenix during the course of the second annual Glen Buxton Memorial Weekend in October ’99.

So could this on-going détente between Bruce, Cooper, Dunaway and Smith ultimately develop into something a little more substantial?

“I would work with those guys in a second,” Alice asserts, before cautiously stipulating, “if it was the right project. I don’t know how we could ever do it authentically without Glen. Mike… [Alice briefly sucks thoughtfully on a tooth] Well, Neal and Dennis are easy. I’ll just say that. They both still play great, but I don’t know if they could do an entire tour. I mean, I’m in really good shape, but we’re not twenty-eight any more.”

“I can’t say whether it’ll ever happen or not,” Neal Smith says, “but if it does it will be something that all four of us will decide upon democratically. It won’t simply be Alice saying: ‘Hey, guys, let’s get together’. And if that time ever does come there would be nobody happier than me.”

“I said to Shep Gordon on the night that I played on School’s Out with Alice at Wembley in 2002,” Mike Bruce recalls, “that it would be nice if we got together to redo the Billion Dollar Babies Show for Europe – do the songs on the same stage set, with Mick Mashbir and Bob Dolan. We never toured Europe with that show.

“I’d love to see something happen with the four of us, but it’s up to Alice to suss it out and put it into his game plan, because he’s the figurehead. The impact of anything that we did would be most felt by him. If it were a success the critics would say he should have done it sooner, and if it were a failure it would be: ‘So, you don’t have it any more, huh?’. So I guess Alice is between a rock and a hard place.”

“Well,” Dennis Dunaway concludes with a sigh, “Neal and I have been making that offer to Alice for thirty years now. I mean, he was supposed to sing on the Battle Axe album, but we couldn’t get a return phone call. It’s certainly not Michael, Neal or I, or even Glen, that have kept this band from ever getting back together. That part I know.”

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 67, in April 2004. In 2025 the Alice Cooper Band announced a new studio album, their first together since 1973. The Revenge Of Alice Cooper will be released on July 25.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.