Ronnie Montrose’s bulldog Lola is dead. The man who created the blueprint for American hard rock, gave Sammy Hagar his first big break, then saddled him with such an inferiority complex about his abilities it took him years to overcome it – is on the phone. He’s explaining that both he and his wife/manager Leighsa are bereft over the loss of their pet and they would like to cancel our scheduled interview.

Given the circumstances, that would be a perfectly understandable reason to call it off, except that for the past two years, the guitarist has dodged my attempts to chronicle his remarkable yet strangely untold story. A man who truly does want his music to do the talking. The problem is, it hasn’t spoken loud enough to allow this self-taught guitar savant – who didn’t pick up a guitar until he was 17 – to get his proper due.But the odd thing is, I don’t think he really cared.

Ronnie Montrose would do anything to get out of an interview. His list of excuses included being “on tour”, “scheduling”, “travelling”, having had “very little sleep” and even mixing me up with a Nordic death metal writer. The death of this most mysterious man on March 3 [2012] is just the latest tactic to avoid talking about a life that most rock stars would be eager to shout about.

“The thing that I cherish the most is that I fucking survived,” the guitarist told me in one of a series of short phone conversations we did manage over the past couple of years. He wasn’t just talking about the prostate cancer that sidelined him from 2008- 2011 and would, sadly, unexpectedly, finally claim him.

“I survived this gauntlet of life… Your life is a series of obstacles thrown at you that you ducked and weaved and figured out how to navigate, and what happens then is just the luck of the draw. It’s the turn of a friendly card. You either get it or you don’t. The things I’ve been through in my life, I actually wouldn’t change now. There were certain times that I said I wish I could change them but now I realise they’ve made me what I am.

”What is that exactly? I asked.

“A survivor,” he said quietly. “I put a quote on one of my records that said: ‘The only path to here and now is the one you’ve travelled.’”

Ronnie Montrose travelled a long way. Born in San Francisco in 1947, his family moved to Denver, Colorado before he was two. By the time The Byrds had released Eight Miles High he was making regular visits to the city of his birth. By the next year he had moved there. Some say he was transporting nefarious substances between the two cities; others say it was just happen-stance and cheap airfares. But whatever it was, there was a sense that the 20-year-old knew that a cultural groundswell was just about to happen and he wanted to be at the centre of it.

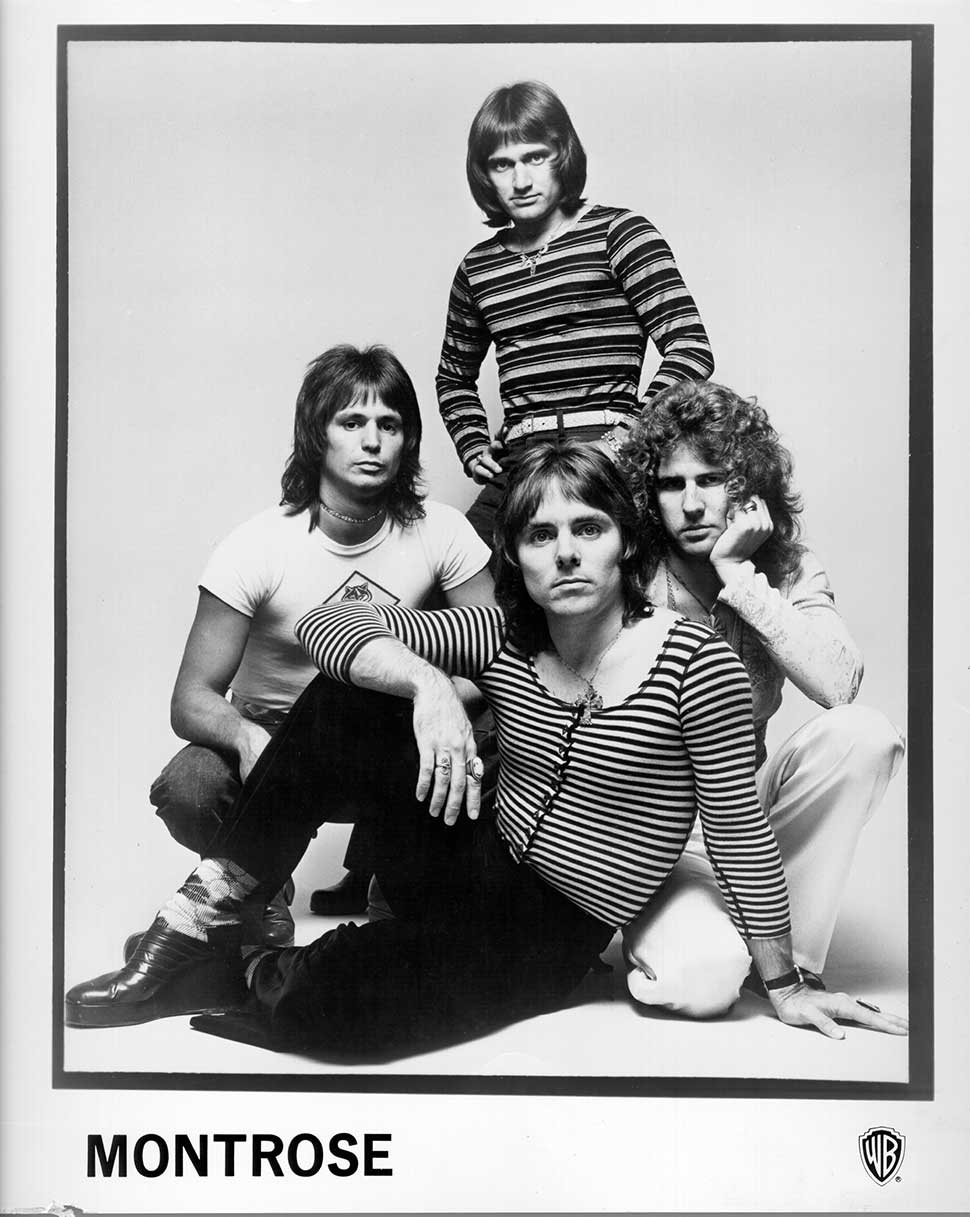

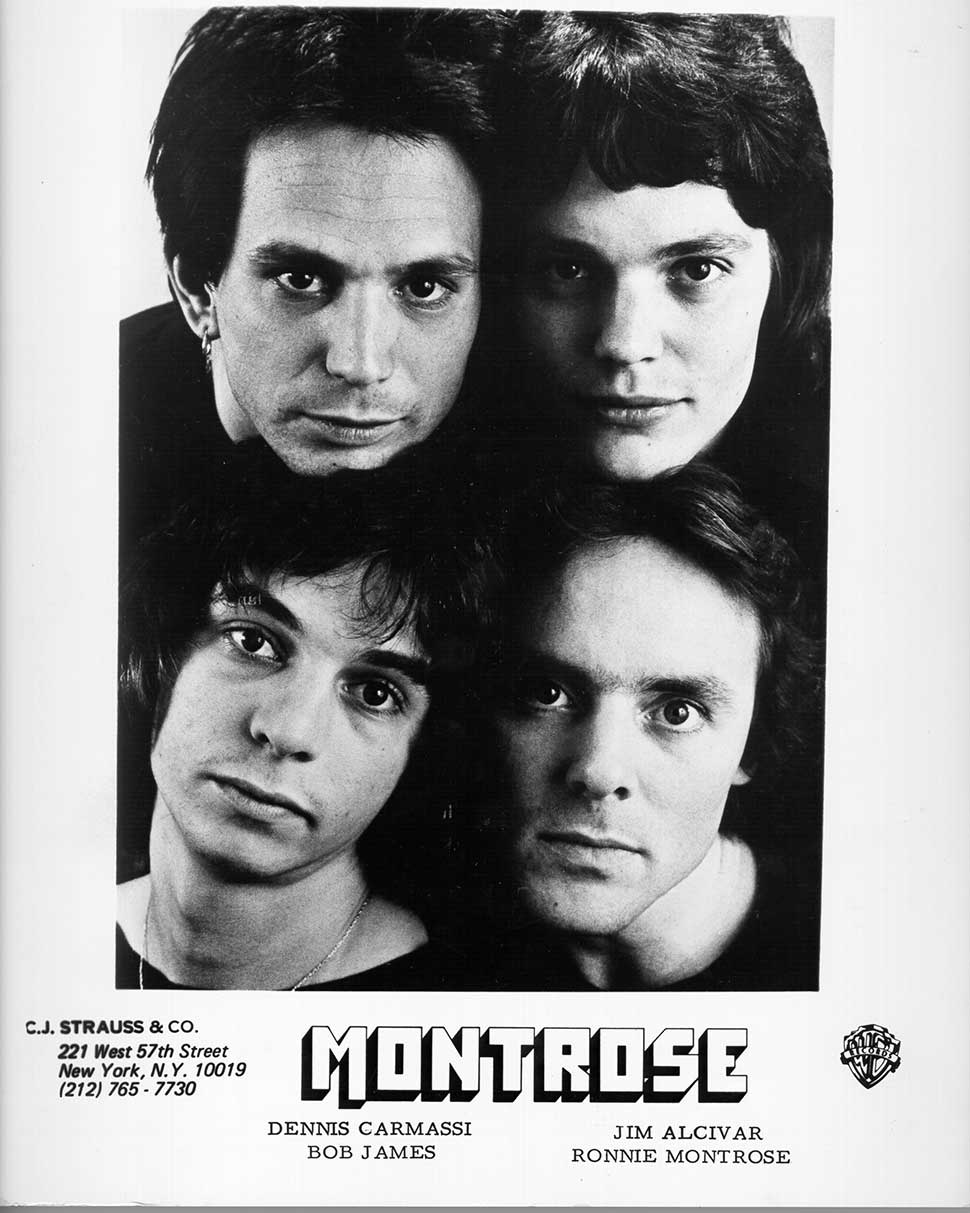

“He’s always been a kind of a visionary,” former Montrose drummer Denny Carmassi tells me on the phone from Oregon. “It’s something he should be proud of. At one point he had everything figured out. The playing, the chops, the chemistry. And you can’t forget the haircuts. He was a visionary with a great haircut.”

There is one thing you need to know about Ronnie Montrose: he had an uncanny command of place and time – a sixth sense about where he should be, and with whom. You could almost call it geographic or maybe musicological ESP. It’s what led him to arrive in San Francisco just as they were passing out the blotter acid and the beads during the Summer Of Love.

It was the same sense of providence that impelled him to get an apartment in a Victorian house called Thin Blue that housed his original Bay Area band Sawbuck, where one night Buddy Miles brought Jimi Hendrix after they’d played the Fillmore in the Band Of Gypsies.

It was certainly serendipitous when Montrose got a gig doing carpentry work for rock impresario Bill Graham and his partner, producer David Rubinson, when they had the Fillmore record label in San Francisco. Building wall partitions for their shared office space was exactly the right place to be when Van Morrison called the office looking for a new guitarist. He auditioned and got the gig.

“I didn’t have total confidence in my guitar playing then,” said Montrose. “Not at all. But I went to audition. How could I not? This was Van Morrison. Gloria, Van Morrison. Them, Van Morrison. There were probably 10 guitar players out there and they all had their little amps and their guitars and they were sitting in chairs out in front of the Lion’s Share where the audience would sit.

“He called us up one at a time. It was the weirdest thing but even before he called me I knew I had the job. Because I knew I belonged there, and it was like this supernatural thing. I knew it from the minute he asked me where I was from. I told him: ‘Denver, Colorado.’ And he told me, ‘Okay. You’re in.’ What I didn’t know at the time was, he loved cowboys – he loved the whole Western thing. It wasn’t until later that I knew that. Peter Wolf told me later that Van called him and said, ‘Wolf, I got myself a cowboy.’

“I had the same feeling when I went out to audition for Edgar Winter’s band. I played on a friend of mine’s demo and Edgar heard it. The friend called me up from New York and said Edgar Winter wanted me to fly to New York too, he’s looking to put a rock’n’roll band together. ‘I’m a California hippie. I don’t want to do that,’ I told him. ‘I don’t want to go to New York, and you better give me a round-trip ticket so I can come back home if I’m not happy.’ I asked for it, but I had that feeling that they were going to hire me, and I secretly knew I’d never use that return portion.”

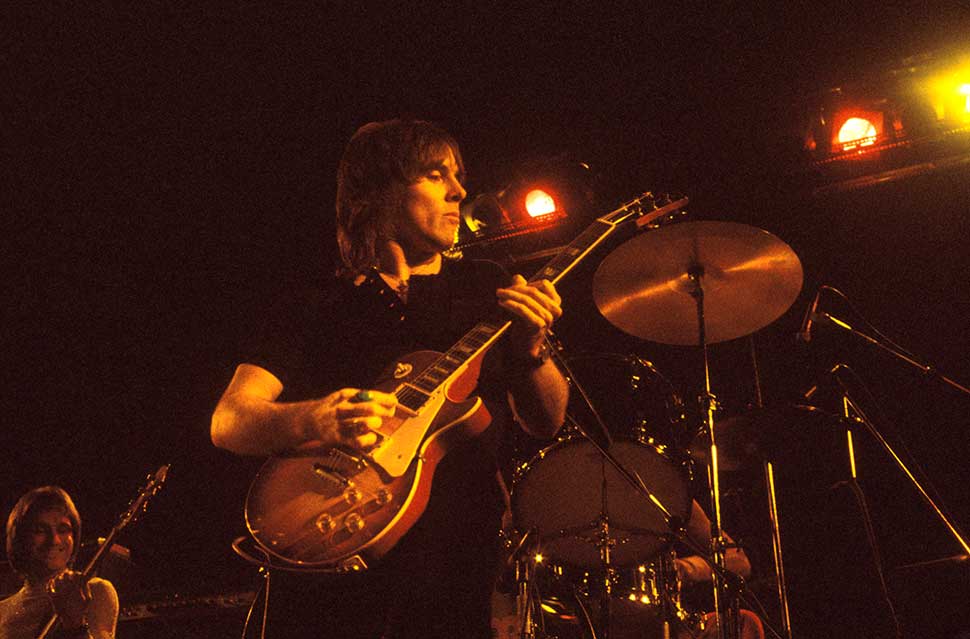

Through his work with Morrison, Montrose met former Harpers Bizarre drummer Ted Templeman, who was producing Van’s Tupelo Honey, only his third job as a producer. The soon-to-be-famous Templeman told Ronnie if he ever wanted to do something on his own to call him. Ronnie never forgot the offer. “Ronnie has always been a very creative guy, ” Templeman says, from his home in Los Angeles.

“If you listen to the Van Morrison records it really foreshadows a lot of Ronnie’s brilliance in music. The song that I really love is Listen To The Lion.”

Templeman then sings Montrose’s guitar part.

“Ronnie was so great at those octaves. I told him, ‘Get together with Sammy [Hagar]’. Sammy was working in the Fillmore in an R&B thing; I thought the two of them together made perfect sense. And it did. I loved doing those first Montrose albums. In fact, Van Halen took everything from that first album. They even wanted me to use Ronnie’s amp,” the iconic producer laughs. “Even Billy Idol’s guitar player Steve Stevens took a lot of stuff from that album. Especially from Space Station #5. You can hear it on that early Billy Idol album. And Ronnie was real creative in Edgar Winter’s group…” Templeman trails off.

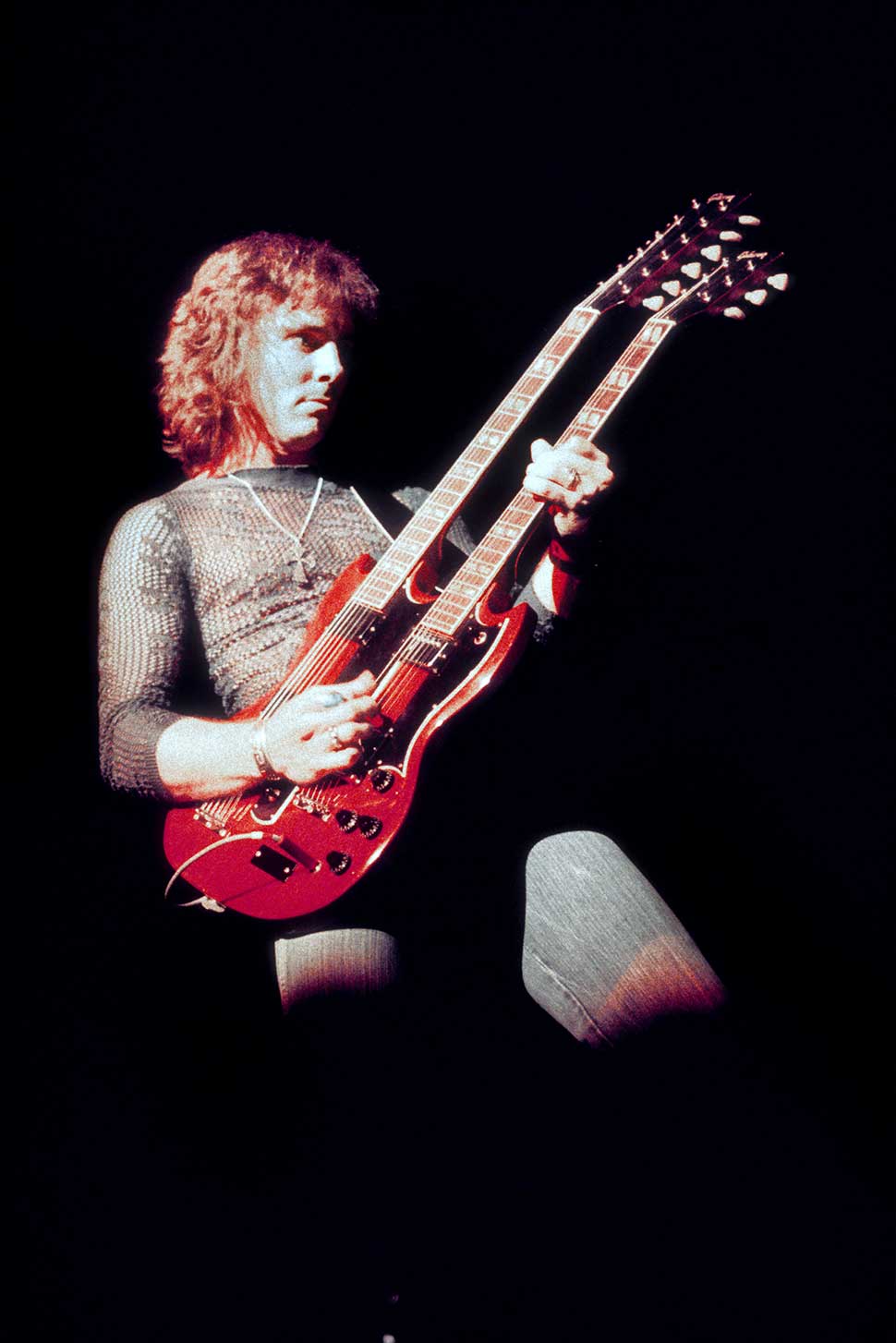

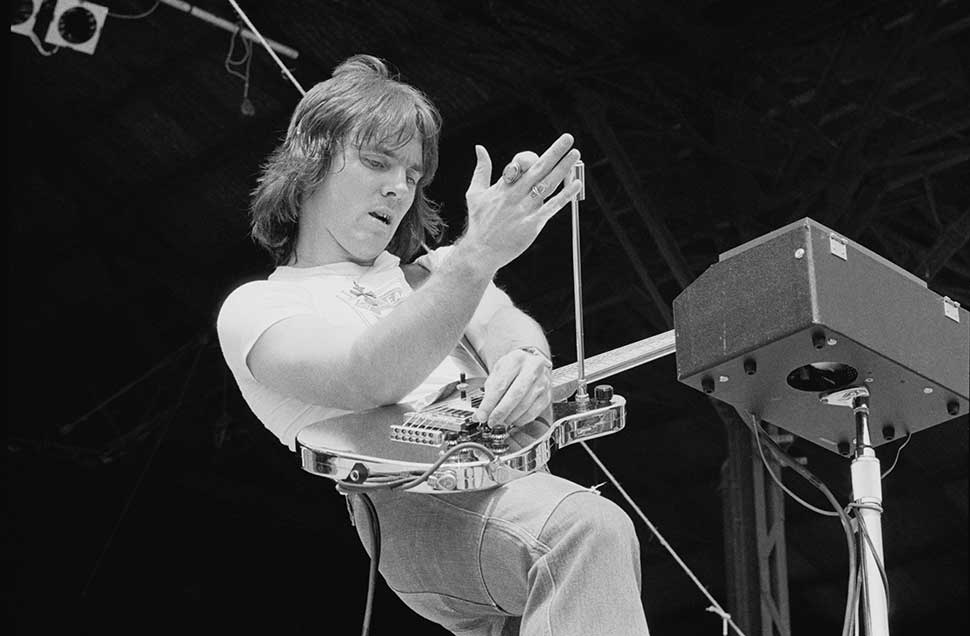

As the guitarist for Edgar’s group he played two solos simultaneously on the band’s second single Free Ride to give it an Eric Clapton feel, and turned Frankenstein into a mathematical thrill ride up the Billboard chart with its psychedelic embellishments and finessed guitar runs – earning its instrumental freak-out a place in the classic rock pantheon along with Free Bird and Stairway To Heaven.

This is where Montrose developed his signature sound. Rock guitar wasn’t Montrose’s forté when he joined the Edgar Winter band. “He so much wanted to do that whole rock thing that he encouraged me,” Montrose confessed. “It was the most exponential jump I made, and I had to do it. I don’t want to call it a struggle. It was a sense of need, that I needed to survive this gauntlet that had been dropped. For me, it literally was sink or swim. My grasp of the reality of the fact that I was in the Edgar Winter Group, and I had better start delivering this heavy guitar music. Now. Because I hadn’t done it before. I was with Van Morrison. I was, like, Tupelo Honey.

“My watershed was when we were in Pittsburgh we did this song Tobacco Road. I was playing my rudimentary scale stuff and I heard some guy in the crowd go: ‘Play some fucking vibrato, man.’ And it hit me so deep, I go: ‘You know what? You’re right.’ So then I started realising that this was a voice that needed to be brought out.”

- Every song on Van Halen I ranked from worst to best

- Sammy Hagar: "What do you do with $80 million? Anything you want!"

- Q&A: Edgar Winter

- Montrose: Reissues

It was a serious dive into rock guitardom. While a sonic innovator and an important component of the success of Edgar Winter’s They Only Come Out At Night, the guitarist was not casting his lot in with rock’s albino futurist jazz-funk fusion for any extended period of time. “Edgar used to say to me: ‘Ronnie, I’m just trying to do my thing and then you always take me somewhere else,’” recalls Montrose.

Pretty soon, the guitarist realised that he actually needed to be somewhere else.

It would be safe to say Montrose was in Winter’s band, but not of it. There was always something removed about the guitarist, holding himself at a distance from the rhythm section, bassist Dan Hartman and drummer Chuck Ruff. As for Edgar Winter, those feelings were complicated. It was the latest in a repeating pattern of interactions between the guitarist and the singer in whatever band he happened to be in.

Former Montrose bassist Bill Church, who was both in Sawbuck with Montrose and in Van Morrison’s band, remembers that dynamic very well.

“We got along great, are you kidding?” Church tells me. “On the personal side of things he and I were a lot alike. We became great fishing buddies. We would bring our acoustic guitars and go up to Eagle Lake, places like that to fish.

“But Ronnie and Mojo Collins – the so-called star of Sawbuck, the songwriter and lead singer – they hated each other. So that was friction. That was the start of that pattern. It showed up in Van’s band, too: Ronnie does one album with us, and does half a tour. Then it all ends with Van’s famous quote: ‘Hey Ronnie,’ Van says. ‘When the bus stops, somebody’s gotta get off.’

“It was just the result of a guy who wants to be Jimmy Page, meeting a guy who is a jazz singer and doesn’t even consider guitar a frontline instrument.

“The show when it all came to a head is when we played Pauley Pavilion at UCLA. Normally in Van’s band we’d stay back behind him and just support him. But at this particular show, Ronnie and I decided we’re going to go to the front of the stage.

“Van didn’t get too mad at me though because I had had an eye injury and I was on heavy painkillers, but that was the end of Ronnie right there.

“But everything has a silver lining because immediately Bill Graham hooked Ronnie up with the connection with the Edgar Winter Group.” Once in Winter’s group, that same dynamic reared its head. “I used to fly out to see Ronnie and Chuck Ruff – who was my oldest friend,” remembers Church.

“They both were in Edgar’s band. I didn’t know really at first what he was up to, but he was plotting leaving Edgar because, of course, he and Edgar hated each other.

“I’ll never forget how he pried open his gold record for They Only Come Out At Night, and took a little Exacto knife and cut out the little picture of Edgar’s face – you know how they put a little album picture on the gold record – and then hung it on the wall that way.

“One day he called me up and goes: ‘Hey, I’m quitting Edgar Winter.’ I told him he was crazy. ‘You got the biggest album in the world and you’re leaving?’ He goes: ‘Yup. And if I got the guts to do that, you got the guts to quit Van…’” Until that day came, Montrose shared a house in the upscale suburb of Byram, Connecticut with Dan Hartman and Chuck Ruff. He didn’t live in the main house with the other two, but instead bunked in servants’ quarters that were situated to the left of the main house.

It was another repeating pattern of Ronnie’s.

When he lived in Thin Blue in San Francisco, he stayed with his wife Jill and their infant son Jesse, behind the Victorian house in a refurbished garage apartment, only interacting with his fellow band members when Sawbuck practised in the bright blue house’s upper floors.

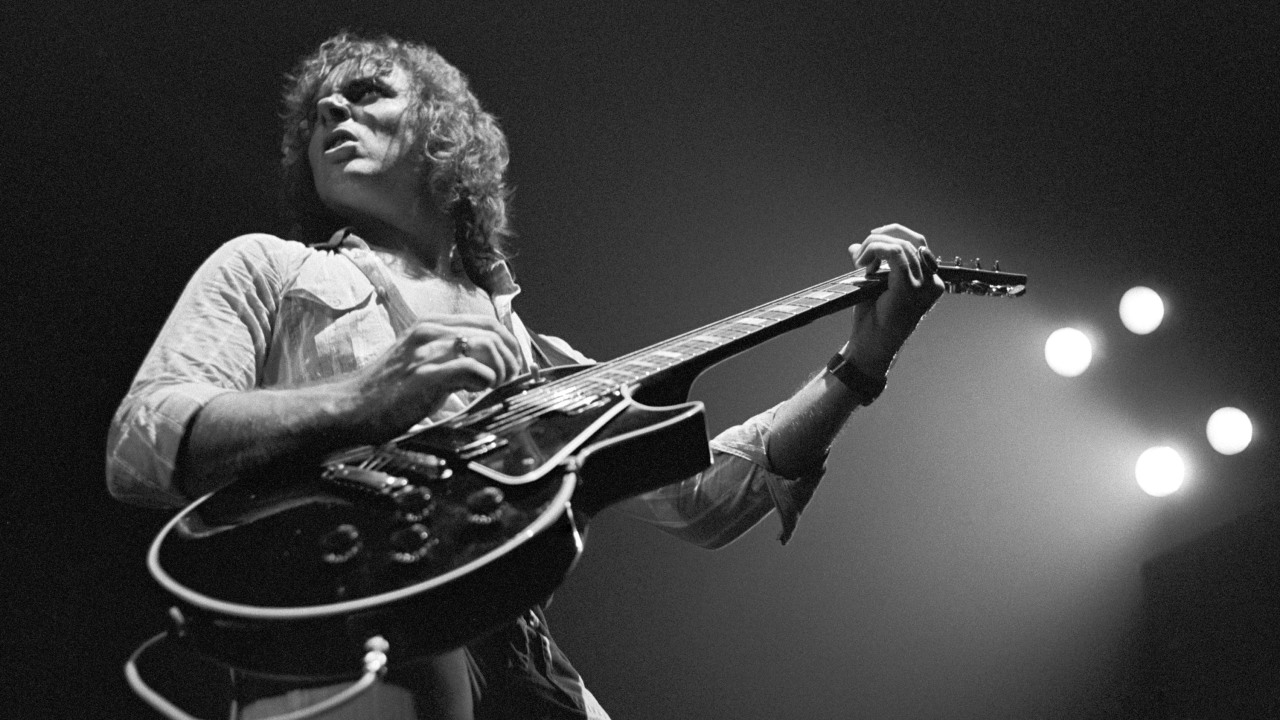

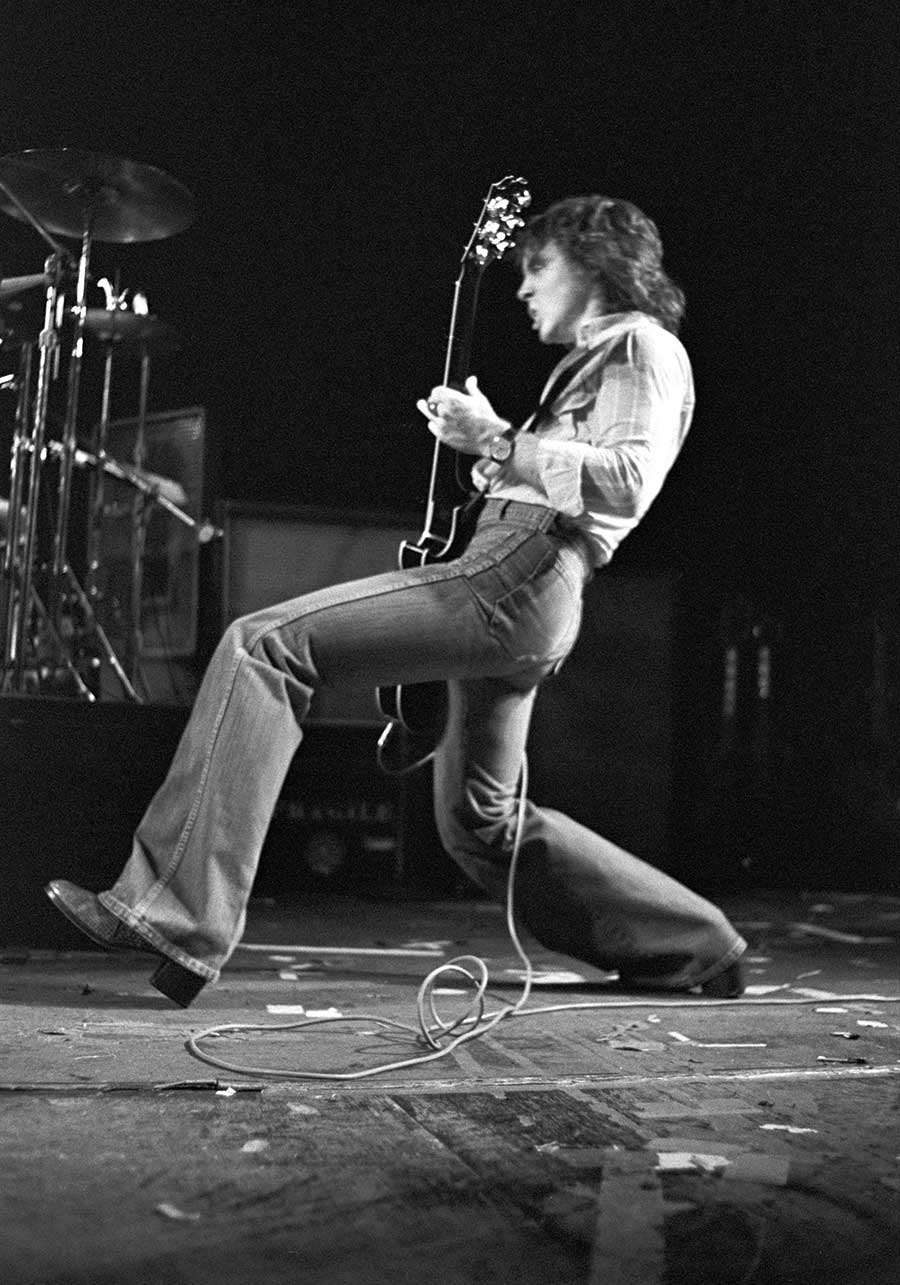

It was outside those two-room servants’ quarters in Bryam, on a bitterly cold day in March 1973, that I got my first glimpse of Ronnie Montrose. Standing just under 5’8”, he could have been a member of the Small Faces, with chiselled cheekbones sharp enough to cut a block of cheese, and a grown-out mod haircut that brought to mind a better-looking Steve Marriott.

But his eyes said it all. Green with dangerous glint, you knew that he was capable of pinning you to the opposite wall if you did something untoward.

“A friend’s mom once told me: ‘Well, honey, gosh darn it, you’ve got some eyes that, when they look at you, you know you’ve been looked at,’” Ronnie Montrose said. It was that kind of look that fed the rumours that one of the reasons that he had been ousted from Van Morrison’s band was that Morrison’s wife, Janet Planet, had taken a shine to the guitarist when they were recording Tupelo Honey, and she wasn’t the only one.

Which was exactly why I was there. I had been staying 10 minutes down the road in nearby Greenwich, Connecticut at the Alice Cooper band’s 40-room mansion where they had just recorded Billion Dollar Babies. I was on assignment to write about the release, and was staying a few extra days at the rambling, Spanish-style mansion with a friend from high school who was the titular girlfriend of Cooper guitarist Glen Buxton. What she really was, was in love with Ronnie Montrose.

Alice and his girlfriend were nowhere to be found, living a more public life in a New York penthouse, and Buxton was back in Phoenix recovering from pancreatitis, making it easy for my beautiful friend Linda and I to make stealth visits in his vintage Grand Prix to nearby Byram, a town more famous for supplying the stone for the base of the Statue Of Liberty than it was for housing most of the members of the Edgar Winter Band.

I was there the week that Frankenstein had entered the Billboard chart, beginning its rapid climb to the top, and the band members were in a rather jubilant mood. All except Ronnie. He seemed curiously nonplussed by the accomplishment, as if he had other things on his mind. It turned out that he did.

Two months later, he would be on his way back to California to form his own band. But no-one knew it at the time. Especially not my friend Linda, who hooked a proprietary arm around his neck and kissed him full on the lips.

“Are you ready to go baby?” she asked him.

“Almost. Let me grab something.” Montrose disappeared into the bedroom, returning with a brown leather bomber jacket and a pair of cowboy boots. The three of us squeezed in the front seat of the guitarist’s compact and headed forManhattan. They promised to take me to the apartment of a fellow rock critic in Chelsea. But traffic was appalling on that Sunday night and they were running late for their rendezvous at Johnny Thunders’ apartment. So Ronnie made a unilateral decision to drop me off in Times Square instead, an idea that terrified me, given that this was my very first trip to New York.

“You’ll be alright,” he told me blandly, brooking no room for argument, before depositing me in this stewing nest of brilliant neon, fast-food joints and scowling humanity.

Until this year, that was the last time I ever saw Ronnie Montrose. ‘See’ being the operative word.

My search for Ronnie Montrose has been nothing short of a quest. Video gamers know there are several types of quests. Typically, there’s the slay-the-dragon quest, the rescue quest (where you find someone and bring them back to safety), the fetch quest, where you find an item – a weapon, a sword, or maybe a key – and retrieve it, and the escape quest, where you are captured and must find a way out.

If I look at it honestly, I think mine was a combination of at least three of them. As for the slay-the-dragon quest, if anything, Montrose – the debut album his own band released in 1973 – is Ronnie’s own personal Loch Ness monster. Until maybe three years ago, he would do anything in his powers to drive a stake in its heart.

“Ronnie said to me: ‘I’ve been talking about this record for 35 years, I’m tired of talking about it,’” Montrose drummer Denny Carmassi tells me. “I think he’s making a big mistake by looking at it that way. It’s something he should be proud of. “But Ronnie Montrose is proud of other things.

“The main thing I felt, when I did my first record, was I just felt happy about my sense of accomplishment, that I had done something. Even with Van Morrison it was like that.”

This quest began a little over two years ago in the winter of 2010. Classic Rock had heard that Ronnie Montrose lived near me outside of San Francisco and asked me to track him down and see if he’d consent to an interview. He’d been off the grid for a few years and people were starting to wonder if the guitarist was still with us.

He was, although he had gone underground for about 18 months after a fight with prostate cancer, not even picking up a guitar for over two years. But he hadn’t perished, and had beaten the disease – without undergoing chemotherapy. Which, given the musician’s formidable will and complicated belief system, seemed entirely possible.

After about two months of phone calls, internet searches, calling acquaintances of acquaintances and querying venues where Montrose had recently played, I got my first break from a friend whose wife is a wedding photographer. I had complained to him that I was about to hire a private investigator to find the missing musician, when he told me to save my money.

“I see him at weddings all the time,” my friend told me. “His wife is a florist and an event planner and he helps her carry in the flowers.”

My friend gave me her contact info, and the next day I Googled her and found that she was indeed an award-winning florist. We exchanged cordial emails and she promised that her husband would contact me soon. To his credit, he did, and we planned to meet for an interview. But somehow the date came and went. I emailed again. And again.

Plans were tentatively made and not-so-tentatively broken, when all the while he would play local shows and appear on hard rock radio stations, telling the same rather sanitised story of the time when Montrose was at the top of rock’s slag heap.

It was as if he wanted to downplay his own legacy.

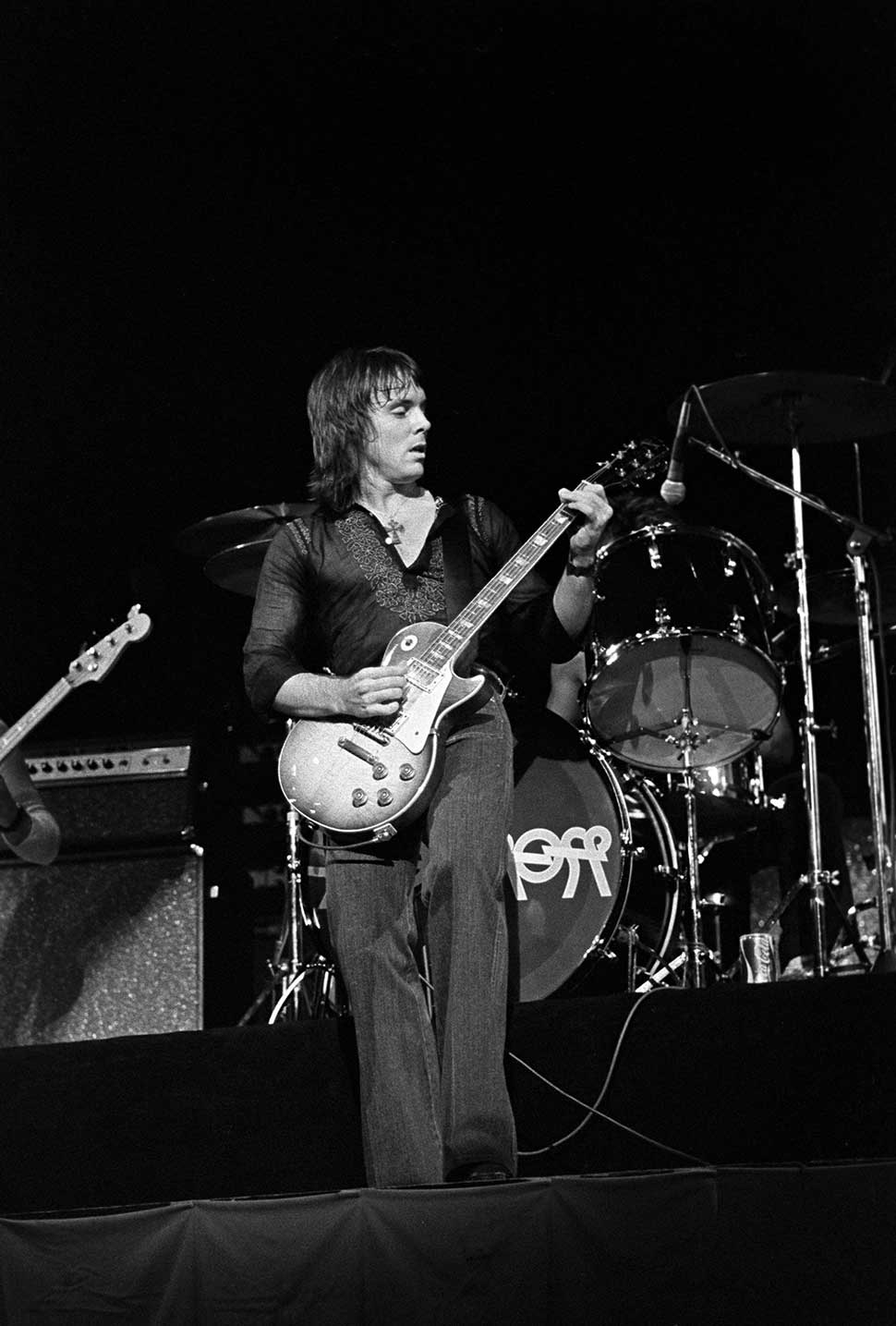

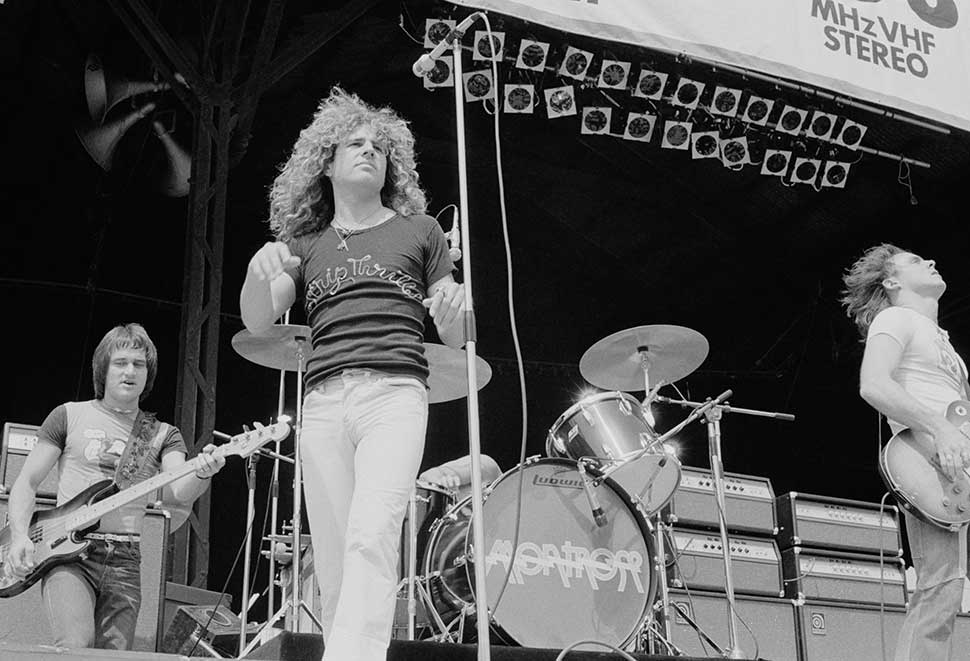

I wondered how he could discount the impact that the fully realised debut Montrose album had on creating the blueprint for what was to come. It left clues as to where rock should be headed in a post-Altamont future – looking forward instead of back for inspiration. Montrose has been called “a pillar of stone that holds up the house of rock” and, in Sammy Hagar biographer Joel Selvin’s words, “a song like Rock Candy is a cornerstone of hard rock upon which a whole school of music was built”.

Not to acknowledge the album’s enduring influence seemed like heresy.

I was appalled when I heard Montrose call in from his car barrelling down California’s freeways to banter with some radio DJ in Oregon, blithely skipping over the reason he dismantled a band that was poised to challenge rock’s mighty élite.

A band that had enough firepower, audacity and talent to knock bands like Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple off their exalted perches on rock’s Olympus. Montrose even attracted the attention of the then often-comatose Keith Richards with their version of the Rolling Stones’ Connection.

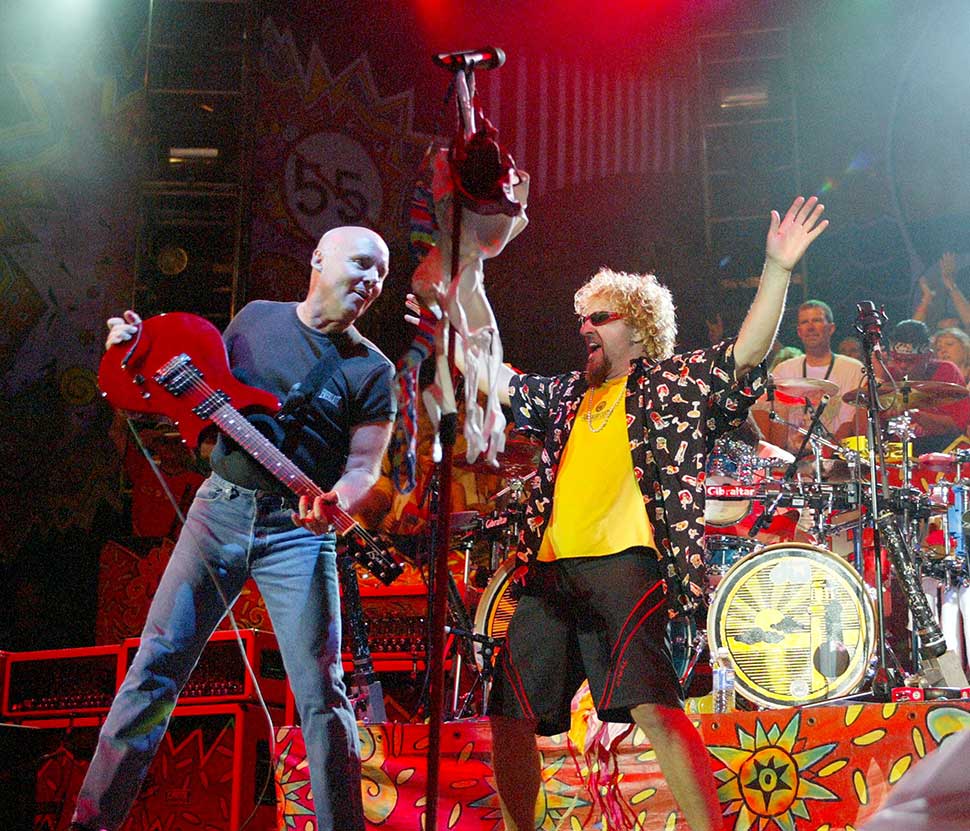

Richards came to see the band when they were opening for Little Feat in Amsterdam, and left singing their praises. Ronnie’s downplaying of this legacy is something that confounds Sammy Hagar to this day.

“I was so sure that we were going to go all the way that I had an astrology chart drawn up the day Montrose was formed,” the singer tells me over the phone from his home in Marin County, California. “I thought it was going to the next Led Zeppelin, Rolling Stones, Beatles, whatever. I mean that was my ambition in that band, and if Ronnie wouldn’t have fired me, I was definitely a lifer there. I was just naïve. I didn’t know what I was doing and I was really pushing for it to go all the way to the top.”

But after two albums, Montrose fired the man who came to be called the Red Rocker.

“Between you and I, Ronnie ruined that band. He killed that band. It wasn’t anybody else’s fault,” Hagar huffs, still rankled almost 40 years later. “I rubbed him wrong by accident because I was ambitious and I wanted to be a star. I wasn’t trying to step on him or prevent him from being one himself. I wanted him and I to be the stuff. But for some reason Ronnie didn’t want to share that with anyone. He didn’t, and he ended up firing everyone and becoming a solo artist. We always joke, the other guys in Montrose and me, Denny and Bill. I say that Ronnie fired me – fired everybody – and finally fired himself.”

I was beginning to feel like maybe I’d gotten the boot too. But then out of the blue, Montrose mailed me and told me that he was performing at the Marin County Fair with Robben Ford. I made plans to go, but events conspired to keep me on my side of the Golden Gate Bridge that night. Fatal mistake. The emails stopped and I realised that was probably a test that I hadn’t passed.

Months later Classic Rock started nudging me again about getting Ronnie Montrose to talk. I picked up the search again, and they tried to make contact through official channels. After a heartfelt email to Montrose’s booking agent, the magazine got a response within days from the guitarist’s wife-cum-manager, who agreed to set up an interview.

This started another round of emails and appointments made and broken. Until the Sunday before Halloween 2011, when the musician and I finally spoke on the phone.

About five minutes into the conversation he said:“I know you, don’t I?” “I’m not sure I’d say that we know each other,” I answered. “But we have met.” “From a long time ago?” he asks, but I’m sure he knows the answer. “Yes, from a very long time ago,” I say simply, not sure if any elaboration would help or hurt.

“Oh, in that case, why don’t we meet and do this interview in person,” the musician suggested, as if all my requests for an in-person interview had never made it through.

“That would be lovely,” I agreed, half-realising I had just made another tactical error. I should have pressed on and insisted that we continue on the phone as previously planned. But I agreed to meet with him at an editing facility owned by a friend of his in downtown San Francisco, where he assured me we could talk without being disturbed.

Convinced that I had finally made a breakthrough, and that the great, in-depth story of how this guitarist had anticipated the future of American rock back in 1973 would finally be told, I began to transcribe the interviews with the other members of the dream team. The composite picture I get of the man is markedly different, equally complicated, but the one thing they all agree on is that he was preternaturally talented. And because of that, despite the psychological ramifications, they all decided to cast their lot with him. And make no mistake, there were ramifications.

“I don’t know if Ronnie will ever let you interview him,” Sammy Hagar warns me. “You can never forget that he’s a mind-tripper. At least I can’t.”

Neither can Bill Church, who was the first person Montrose contacted about forming a band, and the last to finally get hired.“I think it had something to do with their old ladies,” Sammy Hagar confides. “They were friends,but I think Ronnie just wanted to torture him.”

Which he did for three weeks. He had his old pal from Sawbuck and Tupelo Honey days at the rehearsal place, while he auditioned a string of bassists. “I kept saying, oh, he’s cool, man, let’s use that guy, when we were looking for bass players,”Sammy says. “And Ronnie made Bill Church sit there in the rehearsal studio while he tried out Pete Sears, and Ross Valory who ended up in Journey.

“He tried out at least five or six bass players right in front of Bill, and every night after the other guy would try out I’d go to Ronnie: ‘You know, that guy was cool.’ Like Pete Sears was good and I’m going: ‘That guy was cool, but Bill Church, man, he’s like our buddy, man. He’s like cool, he’s fun.’ Finally, he got Bill in the band. But after the first album and tour, he fired him.

“Nobody even asked why, because Ronnie was just becoming quiet. We all feared him because we knew he was wacky and we didn’t know who would be next, and nobody wanted to get fired because that was our meal ticket, number one. Number two, we all believed in the band.”

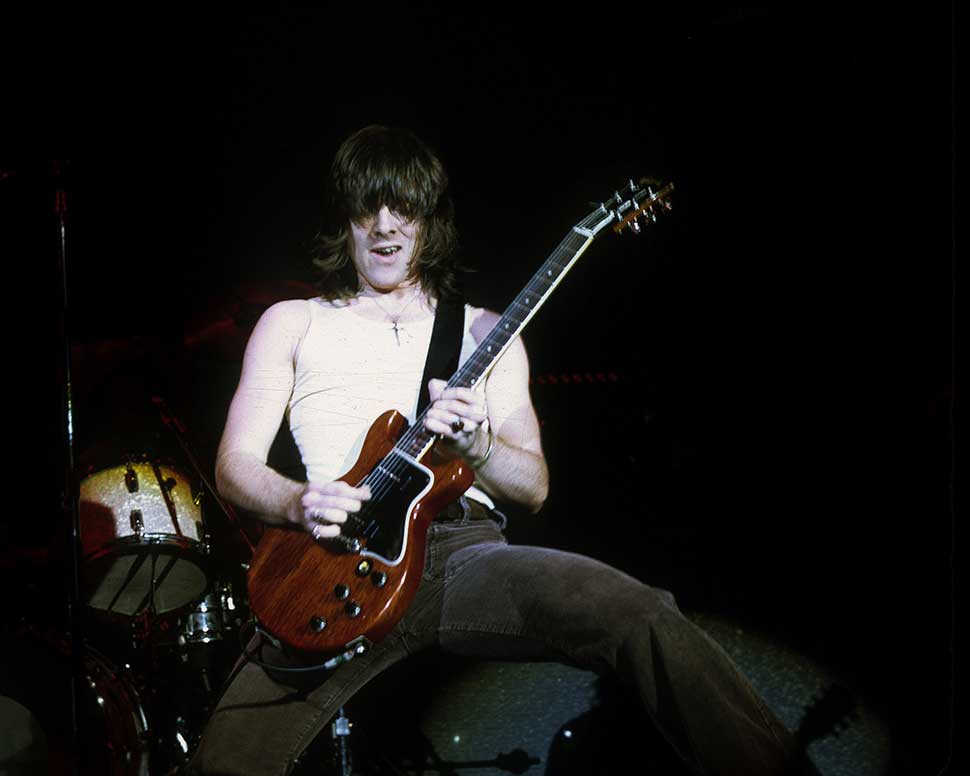

Montrose was Sammy Hagar’s proving ground.“The biggest lesson I learned was how to perform,” he says. “I learned how to go out on tour. I learned how to make a record, I learned how to write songs, and I learned how to deal with a major producer like a Ted Templeman. We had Dee Anthony, one of the biggest managers, so I learned from him. I learned everything but I really learned a lot about playing guitar from Ronnie.

"He was my first real guitar teacher because he didn’t allow me to play guitar in the band so I just watched him every night. And I’d go back to my room and I had my little Les Paul in there. I learned how to play heavy metal guitar from Ronnie Montrose.” It wasn’t to last though, and during the band’s European tour Ronnie had decided that the flaxen-haired singer, who people were starting to refer to as “a pint-size Robert Plant”, was commandeering too much attention.

Bill Church recalls that things began to unravel between the pair during a meeting about the band’s percentages. Out of the blue, Uncle Dee [Dee Anthony] turned to Sammy and said: “Young man, you’re going to be a star.” Ronnie came unglued.

And that, says Church, was the final nail for those two guys.

Hagar remembers it quite differently.

“All of a sudden Ronnie started wearing a white, straight, like a business man’s white shirt – long-sleeve with the sleeves rolled up right above his wrist. He started wearing blue jeans and pair of tennis shoes. And I’m going, wow, the dude’s looking like a street guy, like a business guy just got off the job, sports coat and tie off, put on some tennis shoes and came on stage. I wasn’t digging it. Then he started telling me: ‘Hey, man, you’re getting too dressed up. I want us to be rough and tough, I want to strip it down’. He just did everything the opposite of what I wanted to do.

“Finally he told me in London, at Wembley Stadium opening up for Status Quo, not to come any farther than where your microphone stand is on my side. He didn’t want me running around stage, so instead of saying, ‘don’t run around on stage,’ he just said, ‘don’t come on my side of the stage.’

“Finally, after enduring so much, I started getting pissed. I said to myself: ‘I’m going to kick this guy’s ass if he keeps fucking with me.’ He was just really trying to keep me down and back and prevent me from shining. Then a week later I got this review in a magazine in Belgium, where we were starting to get real big. It had a picture of me in the newspaper and was giving me a lot of love in the band, ‘the new shining star frontman’ or some shit. The next day Ronnie fired me in Paris.

“I swear, I’m not exaggerating,” continues Hagar.

“This is the truth. I was in the backseat, really sick. I ate some mussels in Belgium and I had really bad food poisoning. We pulled up to the Olympia Theatre where we were headlining two nights, and Ronnie turns and leans over the front seat and says:‘After tonight I’m quitting the band. What are you gonna do?’“I said: ‘After I finish puking I’m gonna go start a new band. What the fuck you think I’m gonna do?’ I was so angry and that was the last time we saw each other.

"We didn’t even ride on the same airplane home. Denny and myself and [BillChurch’s replacement] Alan Fitzgerald said: ‘Hey, let’s start a new band. You know, fuck him.’ We got home and Denny and I started rehearsing some of my songs. But then Ronnie called everybody else up and said, ‘Hey, I got a new singer.’ So they of course threw in with him because I couldn’t offer them anything. I didn’t even have a record deal.

“But you know, he did me a favour,” Sammy says, drawing the phrase out a little too long.

“Actually, I’m so grateful that Montrose did break up because it threw me out into my own and made me do what I’ve done. If I wouldn’t have maybe been thrown out, I could still be in that band. We could be Aerosmith right now. Which wouldn’t be a bad thing, just that we’d be unhappy. I’d be an alcoholic, would have been in rehab with drugs over and over again, probably. And probably wouldn’t be as rich and famous as I am.”

Denny Carmassi isn’t as sanguine. “I think Sam would have loved to have stayed with that band. He talks about it to me all the time. We could have been huge, as big as Aerosmith, but it was Ronnie. Just look at his career. Look what he’s done. I mean, look how many band she’s had. Look how many opportunities he’s had. And each one ends up the same,” says Carmassi, taking a breath.

“He’s got a history of doing that. There’s a pattern there. He’s got this thing about sharing the spotlight with a singer or someone else. At some point he has to realise that he has to. All the great ones have done it. They all have a foil that they feed off of. There’s Jagger and Richards, and Steve Tyler and Joe Perry, Neil Young, Stephen Stills. Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth. They keep it together. But Ronnie just would walk away from it. I mean he walked away in the middle of a tour.

"He did that with [his next band] Gamma. Just before I went to play with Heart. We were right in the middle of a European tour with Foreigner and he called me up about three in the morning. He said: ‘I’m going home. So I just want to let you know that everything will be all right. Let the dust settle, but I’m going home.’ He’s his own worst enemy.”

But he remained one of Carmassi’s best friends.

“You know something else? Ronnie is brilliant, man. I’ve played with a lot of guitar players, a lot of guys with big reputations, and Ronnie is as good as anybody I’ve ever played with. A lot of respects better. He’s just got it. I played with Coverdale Page, and Ronnie was right up there with Page. He doesn’t take a back seat to anybody.”

I cross the bridge to San Francisco on a bright,dazzling day, the kind that makes people want to move here. I find a parking spot, and optimistically put two hours’ worth of quarters into the meter. The studio is in a charmingly weathered terracotta building, decorated in the muted colours of a Tuscan sunset. The rugs are expensive, the wood panelling is polished to a burnished glow, and the receptionist is solicitous.

Finally, after about 10 minutes, Ronnie Montrose makes an appearance. He looks very little like he did when I last saw him. His swagger and demeanour are intact; his posture perfect, but his sculptured shag haircut is gone, replaced by a shaven head. His iridescent cat’s eyes are hidden behind blue-tinted glasses and his rail-thin body is filled out to much healthier proportions. Gone are the platforms, bell bottoms and shirts unbuttoned down to there; in their place sturdy but expensive work boots, well-cut jeans and a white tailored shirt, with the sleeves rolled up almost to his elbows.

While his rock star look is gone, the attitude and bearing aren’t. While he does evince a kind of tranquillity that you see in someone who has survived a psychic or emotional trauma, there’s still a sense of… I don’t know: imperiousness. In his presence you just know that things are going to end up going the way Ronnie Montrose wants, instead of what anyone else wants. That’s often true of celebrity. Despite that undercurrent, I realise – just for my own sanity – that I need to know why he kept standing me up for the past year or so.

“You really want to know?” he says, searching my face to see how I’ll react.

“I really want to know.”

“With your name, I thought you were a Norwegian death metal writer. Those metal guys always try to claim that Montrose is a metal band, when we weren’t. So I figured that’s what you were up to.”

For the record, I am not Norwegian, a man, or a death metal fan. I get the feeling that things aren’t going to go exactly the way I want them to. The two of us settle into a windowless room, choosing two ergonomically correct chairs opposite each other.

Montrose closes the door and sits down. I start to ask him a question, and he cuts me off.

“As I was driving in I thought: ‘I have two stories. I have my life story and my music story.’ My life story is something that is so off-the-wall that I can’t share. I mean, I have to be Proust on his deathbed to tell that story. You know, dying and remembering everything that happened to him in his life. That’s not what this is about. But my music story is something I thought might be really interesting, to hear everything that happened tome and from my earliest years, which is not something I want to give up.”

He trails off, and I get the idea that I am really in trouble here. He isn’t really going to let me interview him. Sammy Hagar was right. Ronnie agreed to meet with me, but this is just an audition for an interview. A little like what he did to Bill Church when he asked him to be in Montrose, then kept auditioning other bass players in front of him.

When I asked Bill Church about that, 38 years later he admitted that was true.

“I have to say I just didn’t get it. Like I said, Ronnie had called me up and asked if he quit Edgar’s band, would I quit Van,” says Church. “We hadn’t got Montrose together yet. Then here comes Denny and Sammy, and we start writing songs, and then what happens is that Sammy and Ronnie decide they want to write the songs, not me and Denny. So I went back home, and next thing I know here’s Ronnie. He’s trying out all these other bass players. We’re best friends and I have to go with him and sit in Studio Instrument Rentals watching him audition all these other guys.”

Did that piss you off?

“Yes, of course it did. For example, my good friends Pete Sears and Ross Valory were auditioning. Andy Fraser of Free was on Ronnie’s list – but he didn’t even show up for the audition. I remember the night that Pete Sears was there. I got up and started and jamming with Denny. Pete walks up and he says: ‘You play better bass than I do. But let’s jam, because I play piano.’ We all jammed with Pete on piano and me on bass, and it all felt really stupid to me, with Ronnie’s ego walking on the razor’s edge.

"I came very close to just saying: ‘I ain’t gonna go through this. You go do your little band and I can find something else.’But after almost a month of him auditioning other bass players he finally called me up and says: ‘Hey, the time’s right.’ I know I should say forget it, but all I said: ‘Let’s do it.’ I knew all along that the gig was made for me.

“You probably are wondering why I suffered all that?” says Church, reading my mind. “Because at that time, Ronnie was the best guitar player in San Francisco. And that was enough for me. It still is.”

But it wasn’t enough for Montrose to succeed. Or at least past that monumental first album. Unlike so many infamous pairings, the tension between Ronnie Montrose and Sammy Hagar did not fuel creativity; if anything it lowered the tone.

“It detracted big time from the band,” Church recalls. “And it made for a weaker second album. Ronnie didn’t want Sammy to have all his tunes on the second record. And he iced the cake by trying to sing one of the songs – We’re Going Home. And he butchers it. Sammy is going: ‘Oh boy, I’m the singer, and that’s that.’ Ted Templeman is probably still having nightmares about the day he let Ronnie sing.”

“I don’t want to go Jerry Springer but like it’s the deepest of the deep,” says Ronnie. “My story is the real story. My name is Ronnie Montrose. The band is called Montrose, and all these other guys that we rein this band are peripherals to the real true story.”

“But Sammy Hagar wrote about what happened in his autobiography last year…” I begin.

“I guess compared to Eddie [Van Halen] I got off pretty easy [in Sammy’s book]. What I can say, we were like Jagger and Richards. Tyler and Perry. We were a team, and we worked well back then.”

And then they didn’t.

“But Sammy says…” I persist.

“Only two people know what went on between me and Sam. And I’m one of them,” he says, snapping his mouth shut.

I know nothing else on the subject will be forthcoming.

This article first appeared in Classic Rock issue 170.