No one was more taken aback by the euphoric, near-awed reaction to Lift To Experience’s triumphal performance at London’s Royal Festival Hall in June last year than the band themselves. That night their set reached a high-water mark as the three-piece navigated the tumultuous twists and turns of Into The Storm, the mammoth, 28-minute track that closes their solitary album, The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads. As they preached hellfire, damnation and possible salvation to a sold-out house of 2,500 acolytes, singer-guitarist Josh T Pearson, bassist Josh ‘The Bear’ Browning and drummer Andy Young might have stopped to pinch themselves, just to make sure the entire evening wasn’t a figment of their imagination.

The fact that this was by far the biggest audience they had ever headlined to was unfathomable enough to them. Then there was the fact that they had never before had the means or cause to use their own lighting or sound system, or even written out a set-list. Truly, though, the most remarkable thing about the show – which was part of the Meltdown Festival, this year curated by an admirer of the band, Elbow frontman Guy Garvey – was that it ever took place at all. For at the point Pearson began Into The Storm, it had been close to 15 years to the day since Lift To Experience had last played the song on British soil, and then at a poky club, King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut in Glasgow, on another sticky summer’s night. Shortly after that the band ran aground, breaking up on the rocks of drugs, despair, near-poverty and a sudden, terrible bereavement.

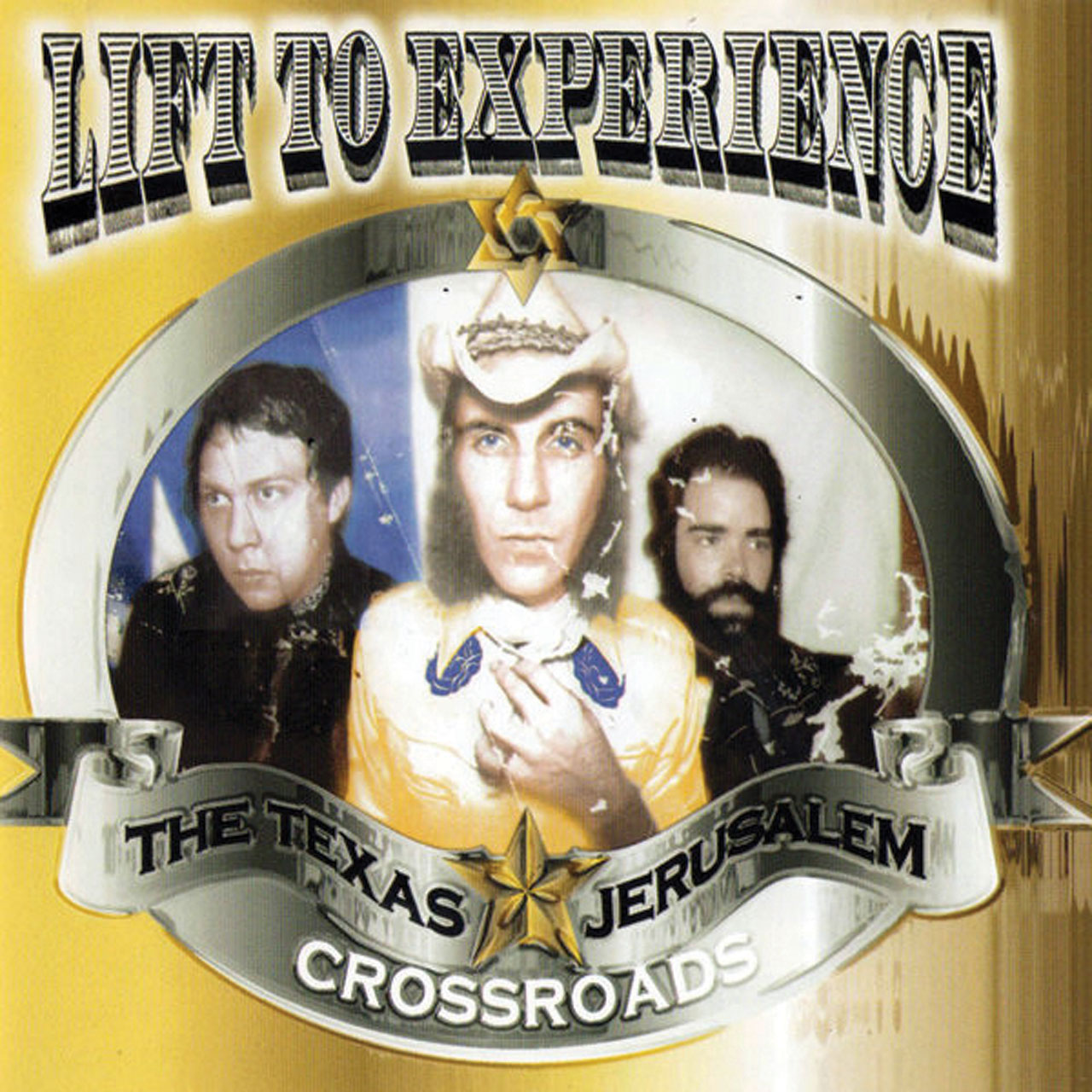

Their comeback, as unexpected as it was protracted, was sparked by the now-imminent reissue of a remastered version of The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads by Mute Records, Pearson’s label as a solo artist for the past six years. A concept album, and a double at that, the record portrayed their native Lone Star State as the setting for the Second Coming of Christ and the last refuge in a Biblical apocalypse, set to a brooding, meandering, lysergic kind of music that shifted like sand across a blazing hot landscape.

Back in 2001, this heady cocktail had received rave reviews in the British music press but otherwise passed almost unnoticed, never having had a release in the US. Indeed it’s only now, as they return from self-imposed exile, that Lift To Experience have begun to be discovered in a broader sense.

Even still, the morning after the Festival Hall show, which won glowing notices in the broadsheet newspapers, Josh Browning had to pack his bags and fly straight back home; a handful of days were all he’d been able to wangle off from his day job making sandwiches at Skeet’s Grill, a fast-food joint off the highway outside Sweetwater in West Texas.

Browning and Pearson were both raised further north in Denton, a small city of some 113,000 souls on flat, arid Texan plain lands. Each came from devout, God-fearing stock, Pearson’s father being a fire-and-brimstone Pentecostal preacher. They first met as kids at their local church, where Pearson sang in the choir. He was drawn to music by the Sunday services, hour-long communal epiphanies during which a full band would summon the congregation to raise their voices, dance and give praise, and by the age of 12 he was picking the strings on his first guitar.

To start with he taught himself to play the opening chords to U2’s Sunday Bloody Sunday,and then a handful of entirely secular songs by the Sex Pistols. Later he grew enthralled by the billowing noises being made by the shoegaze bands of the late 80s and early 90s, such as Slint, Spiritualized and most especially the Irish quartet My Bloody Valentine. By his early 20s he had alighted upon a grand vision of his own.

“My goal was to combine a Jimi Hendrix-style power trio with My Bloody Valentine,” the soft-spoken Pearson says today, sat alongside the more garrulous Young in a basement studio at Mute’s west London HQ, the pair of them f facial hair and denim. “My southern religious upbringing also gave me the impetus to really try to prove myself to a higher being. Such things are important when you have a real, fervent belief in the concept of an afterlife and hell – salvation is free, but you’ve got to earn it. What I really wanted was to try to make a symphony to God.”

Pearson’s master plan extended to the idea of making a trilogy of interlinked albums that would together tell of a final battle between good and evil, fought beneath the big Texan skies. Browning was an immediate and natural ally, but they went through five drummers before settling on Young, another son of a preacher, who had grown up on jazz and also, more unlikely, NWA and the nascent sounds of West Coast gangsta rap. The newly minted trio then holed up in a cramped rehearsal room in Denton and for months on end practised and honed Pearson’s ideas into shape.

In 2000, using $700 Pearson had saved from his wages working in a wood shop, they cut a demo version of The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads. Pearson’s guitar enveloped the 11 drawn-out, restless songs like a storm wind. Feeding gusts of dense, rolling chords and flurries of notes through a battery of effects pedals and a single Leslie speaker, he conjured a maelstrom that was all at once ethereal, off-kilter and powerful.

They mailed copies of the tapes to record companies, then waited for a response.

“The recording was the easy part,” Pearson elaborates. “It wasn’t like we went into the studio and had to work out the kinks. No, this was not experimental music, but cold, hard fact – science. I had planned out everything – the sequencing, the gaps between the songs. It was endgame stuff.

“We sent it out to every kind of label. We got a little PO box. I checked it every day for six months, and then the heartbreak set in.”

Still then reverberating to the sound of nu metal, the American heartlands were not in any way welcoming to a psych-prog-rock extravaganza, much less one with pronounced religious overtones. Undeterred, Lift To Experience set off for the first time to play outside Texas. They had just got to the other side of the state line and into Arizona when their pickup truck blew a rod.

“It was almost as if a lightning bolt struck us, like, ‘What the fuck are you trying to leave for? Go home,’” Pearson recalls with a gallows laugh. “Our first show ended up being in some dive bar in Flagstaff. We’d been drinking all day in there and it just happened to be open-mic night. The kind of place it was, there was a neon sign hung outside that was meant to say ‘Cocktails’, but the last four letters had burnt out so it just read ‘Cock’.

“I remember after we’d played, some old lady walking out onto the street. She didn’t see it was me behind her, and shouted back: ‘I think that’s the worst band I ever heard!’”

Early the next year, Lift To Experience travelled to Austin, for the city’s annual, week-long music jamboree, South By Southwest. It was there that Simon Raymonde and Robin Guthrie – one half of Brit avant-gardists the Cocteau Twins and founding partners of indie label Bella Union – caught them playing another bar gig, on this occasion during a violent thunderstorm. Impressed, the two men signed them on the spot, and The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads was mixed for a European release that June.

After its release the band toured Europe, playing at the Reading and Leeds Festivals, and on bills with the then Pavement mainman Stephen Malkmus, and in France with Elbow. “I guess we made a strong impression on Elbow,” says Pearson. “At all events, we bonded. One night off in Paris, we had a drinking contest, which both bands agreed ended in a draw. We finished up in some gay dance bar, with one of us on his knees and a belt around his neck.”

The record was well met, like an invigorating bolt from the blue, but also spectacularly ill-timed. On September 11, three months after it came out and staked out a moral battleground, two planes were flown into the World Trade Center in New York City. In response, it was a Texan US President, George W Bush, who rushed to war.

“Yeah, well, I don’t want to get into all that, but it definitely sort of clouded things for us,” Pearson says, sighing deeply. “I guess it was confusing for some people who thought we were somehow involved in the whole thing or not.

“Simon Raymonde was also acting as our manager at the time, which was not in the best interests. He wouldn’t licence the record to a subsidiary label in the States because he didn’t want to split the money, so it hadn’t come out there. If you wanted to buy The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads in Dallas, Texas you had to pay double for it, and our fans were broke college kids. This was pre-internet, and so for us there was no encouragement coming in to even have a frame of reference that anyone gave a Goddamn.”

The band returned home to Texas to lick their wounds. Pearson had managed to scrape together $10,000 to buy a small house in an isolated township of 300 people in Limestone County, and he retreated there to write the second instalment of his trilogy. Close to penniless, Browning and Young had to take day jobs just to get by. Their ruinous financial state soon caused other tensions between the three of them.

“It was all just pressure,” Pearson reflects. “You’re making art and not selling out, but you’re not able to buy anything either. This stuff started to infringe on the innocence of before and there was some external expectation there now too. Also, I had felt an absolute responsibility that I had to do this and I didn’t feel that way any more. I’d got it out. I did get about two-thirds of the next record done, but the weight of it was pretty hard for me to lift.”

The final, devastating blow was the death of Browning’s young wife Diane from an accidental overdose, after which Lift To Experience shattered and splintered. Young says: “Most people can make it through a substance problem or a death, but for us, all of those things came along at once.”

They went their separate ways. Young spent time in Manchester, playing with Garvey in a short-lived project they christened Western Arms, and then moved to Austin, and later Portland. Browning formed another band, Year Of The Bear, but in the main knuckled down at Skeet’s Grill. Pearson at first got work doing odd jobs and then, in his own words “went and walked the earth for a while”. He spent six months in Paris and then two years in Berlin, having been drawn to the city by a typically esoteric challenge.

“I went there to compete in the World Beard And Moustache Championships,” he explains. “I entered in the Full Beard Freestyle category as the Texas Tornado – wound my beard up like a twister and stuck a toy car and a plastic cow in it. Turned out I was too avant-garde for the judges, but I met a hot young German girl, and she’s now my wife.”

Eventually, Pearson circled back to Texas, but only fitfully reared his head above the parapet. He played the odd solo show, guested on Bat For Lashes’ Mercury Prize-nominated debut album of 2006, Fur And Gold, and conceived an album of cover songs exclusively about loneliness, though ultimately released just one single, a version of Hank Williams’ I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry. In January 2010, he revisited Berlin and over two frigid winter days, he recorded Last Of The Country Gentlemen, his first album under his own name.

Against a sparse, hushed backdrop of acoustic guitar, piano and the violin of long-time Nick Cave sideman Warren Ellis, Pearson documented the course of a tempestuous, doomed love affair in unflinching detail, each note harrowing and haunted by regret. It was picked up and released by Mute in 2011, to great acclaim from critics and peers alike. Mark Lanegan hailed Pearson as a “one-of-a-kind artist”, while his most reliable cheerleader, Garvey, described him as “the greatest male vocalist of our time”. Pearson toured Last Of The Country Gentlemen and then vanished once more

It was late 2015 when Pearson and his manager of the last few years, Peter Sasala, began the process of remastering The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads, hiring an engineer from Denton, Matt Spence, to spruce up the original recordings. The result, Pearson insists, is LTE’s music as he always meant for it to be heard.

However, a band reunion didn’t become part of the equation until Garvey took on Meltdown duties and Sasala established that there would be a budget to bring them to London. At that point, Pearson, Browning and Young had been in a room together just once since 2001, and then inadvertently when they all found themselves in the same bar one night. Pearson went back and forth between Young and an initially reticent Browning before the Festival Hall gig was finally confirmed, alongside three more intimate warm-up shows in Texas.

“We started practising just a matter of weeks before the first gig,” Pearson says. “For several years we hadn’t even spoken. We were just sore from the car crash of it all and it was easier not to talk – we had to go through our own soul-searching stuff. I mean to say, we’re very sensitive men, volatile and emotional. But I for one am much healthier and happier now. I got a hair and beard cut.

“I still thought there’d been some mistake when I realised we were meant to play Festival Hall on our own. I’m pretty out of touch, and you don’t know how much people are being nice when they say they really like your old band. It was with fear and trepidation that we did it, because we’re purists and respect the past and we didn’t want to stink the place up. But what an honour.”

The Festival Hall show was originally conceived as a belated full stop. However, though it amounted to just eight songs, the show was so intense and so striking, it’s been suggested that there might be a future for the band. Pearson for now remains adamant that their definite horizon stretches no further than the reissue, but he doesn’t rule anything out. After all, he believes in miracles.

“Our endgame was right now, but so far the friendships have maintained so we’ll see what happens, one day at a time,” he offers. “We live now in a new world of light where everything is Google-able, and with the death of romance, but I believe our record stands as a good work, a treasure. And it’s still audacious, daring stuff, man. We’re declaring Texas the Promised Land, not Israel. But then again, Texas is the only state where you don’t require a licence to shoot feral hogs…”

“You can just sit up on the porch and blast them,” interjects Young, beaming, as if this was the most wondrous thing on all of God’s earth.

The reissue of The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads is out now via Mute Records.

First and last and always?

Five more debut albums still awaiting a follow-up…

Blind Faith - Blind Faith (Polydor, 1969)

Combining the talents of Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker and multi-instrumentalist Ric Grech, Blind Faith topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic with this mix of hard rock, plangent blues and pastoral folk, all of it enfolded in one of history’s most unpalatable album covers. One tour later, the band dissolved, yet to return.

Sex Pistols - Never Mind The Bollocks (Virgin, 1977)

The apex of Britain’s so-called ‘Year Of Punk’, Bollocks also proved to be the Pistols’ singular statement. The band’s original line-up have reunited for live shows in 1996 and then again in 2007 and 2008, a shadow of their former selves, but never made it back into the studio – which is perhaps for the best.

Operation Ivy - Energy (Lookout, 1989)

Featuring future Rancid men Tim Armstrong and Matt Freeman, this ska-punk crew out of Berkeley, California split just months after Energy had appeared on vinyl and cassette. Its influence on the blooming SoCal punk scene was indelible, though.

**Temple Of The Dog - Temple Of The Dog (A&M, 1990) **

Conceived by Chris Cornell as a tribute to his former housemate, the late Mother Love Bone singer Andrew Wood, the Soundgarden-Pearl Jam supergroup played their first live shows together in the US last November, but there’s still no word on a second record.

**Them Crooked Vultures - Them Crooked Vultures (Interscope, 2009) **

Relatively recent in this company, it has nonetheless been eight years and counting since Foo Fighter Dave Grohl, Queens Of The Stone Age’s Josh Homme and Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones joined forces for this hulking riff-fest. There’s no sign of there being another chapter.