Bill Graham isn’t happy. It’s February 1971 and the J. Geils Band have just taken to the stage of the Fillmore East in New York on his recommendation. But the crowd don’t want to know. As the band snap into their opening number, the throng strike up an impatient chorus of “Sabbath! Sabbath!” in anticipation of headline act Black Sabbath. The Geils sound is all but drowned out. Annoyed, promoter Graham strides forward.

“Bill had asked us down sight unseen, which he never did,” recalls singer Peter Wolf. “But he had heard such good things about us. So he told the crowd: ‘I invited this band here and they deserve some respect. If you’re not being polite, then leave now and come back later.’ Very few people left. We went on and ended up getting four or five encores. That was the start for us.”

Their debut album had just emerged. A bratty blast of livewire blues and R&B, it pitched originals against rowdy covers of John Lee Hooker, Otis Rush and Smokey Robinson. It was a decent start but, as the Fillmore crowd discovered, the band’s real strength was onstage.

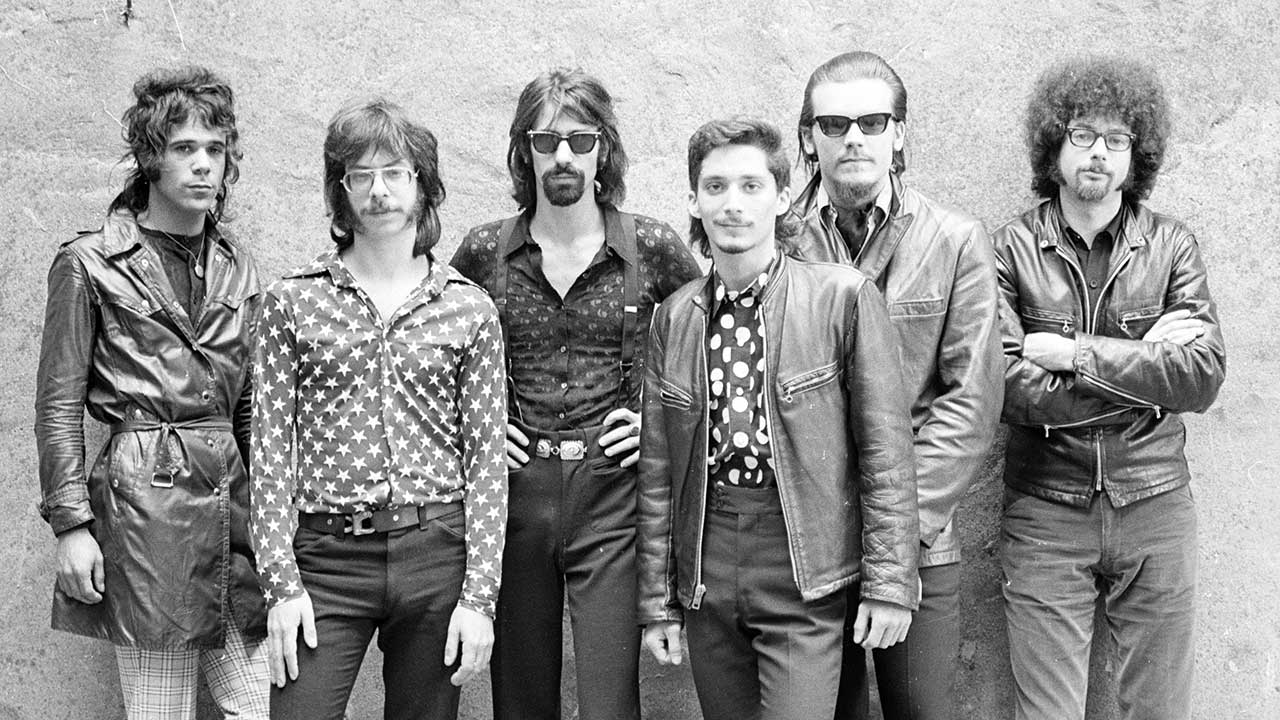

Even then, the Boston six-piece were on their way to becoming dynamic party-starters in 70s America. Guitarist John Geils provided the swinging riffs, harmonica player Richard Salwitz (Magic Dick) laid out fearsome jazz-blues runs, while bassist Danny Klein and drummer Stephen Jo Bladd held a slippery groove topped off by jive-talkin’ Wolf, a hyperactive stringbean who started out as radio DJ ‘The Woofa Goofa’. At a time when their peers were peddling acid jams and extended blues-rock, The J. Geils Band felt like a filthy blast from rock’n’roll’s past.

“We wore leather jackets and boots: ‘We’re bluesmen, we’re not hippies!’” remembers Geils. “It set us apart. Everybody calls Aerosmith the bad boys of Boston, but we were the originals.”

Peter Wolf was born and raised in New York, but by the mid-60s he’d headed up the coast to Boston. As a child, his older sisters would regularly take him to The Apollo, the venerated soul and R&B venue in Harlem. It was there, watching James Brown, Otis Redding and Jackie Wilson, that he’d witnessed the art of stagecraft up close.

“It was an incredible learning experience of how the artist made himself connect with the audience,” he says. “The performer and the song became one. They were almost preaching to the audience. If someone was singing a love song, it was like high opera. They’d tear their jacket off, get down on their knees. And you really believed it; it was total credibility.”

Geils, another New Yorker, had arrived at Worcester Polytechnic Institute as a student in the mid-60s. There he met Dick and Klein and set about forming “a bluesy, folky jug band”, influenced by The Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Studying the songwriting credits on the latter’s first album led to the discovery of Little Walter and Muddy Waters. By the spring of 1967, they’d dropped out of college and moved to Boston.

“We were pretty much modelling ourselves after the Junior Wells-Buddy Guy quartet,” Geils says. “We ended up being the house band at the Unicorn coffee shop downtown.”

The Hallucinations were another young outfit making local waves, who counted Bladd and Wolf among their number. In need of a new drummer and singer, Geils drafted the duo in. With the addition of student and piano player Seth Justman, the J. Geils Band were born.

“It was a fusion between a straight blues band and mine,” Wolf recalls. “The Hallucinations did blues and R&B and were like neo-punks. We had 20-foot guitar chords and we’d jump into the audience. The show was an important aspect of what we did. It was my job to entertain, to make people get up and dance.”

Wolf estimates the first J. Geils Band album was cut in 18 hours, the band bringing their road-tested tunes to the studio. A cover of The Contours’ R&B ass-shaker First I Look At The Purse was released as a single, but business was hardly brisk. The follow-up, 1971’s The Morning After, fared slightly better, yielding a minor hit with a version of The Valentinos’ Looking For A Love. Still, it was hardly a breakthrough.

Aside from debuting at the Fillmore East, 1971 also found them supporting Black Sabbath across the US – the result of both bands being signed to the same Premier Talent agency.

“It really was apples and oranges,” Wolf recalls. “We were coming off as this R&B band playing with tiny, funky, beat-up Fenders. The first place we played was in St Louis, in an old cattle stockyard. It was a dirt floor and you could smell the manure. Our dressing room was the infirmary where they’d put people if anybody got hurt, so they had all these cots. We were sitting there trying to get changed and they’re dragging all these kids in who’d taken too much or were OD’ing. It was almost like we were playing in a foreign language.”

June 1971 also saw the Geils Band return to the Fillmore East for its final night, sharing a bill with Albert King, Edgar Winter, the Beach Boys, Mountain and headliners the Allman Brothers. It was a marathon evening, broadcast live by two New York stations. By the time the band left for their hotel at four in the morning, the Allmans were still on the radio.

“We must’ve done 50 or 60 shows with the Allmans,” says Wolf. “Phil Walden, who managed them at the time, always wanted to manage us too. I remember the Geils Band were rehearsing in Dick and Danny’s apartment in Boston when all of a sudden these two guys walked in: ‘Yeah man, we’re musicians too.’ One of them picked up a guitar and started singing The Beatles’ Blackbird. The other got another guitar and played along. It turned out to be Gregg and Duane. So we became friendly with them even before we started playing together. There was a kind of brotherhood between us.”

Unlike the Allmans, the J. Geils Band had yet to translate the power of their live shows onto vinyl. “We had what they used to call in the business ‘turntable hits’,” says Geils. “They’d play ’em on the radio but nothing was really becoming a hit.”

Enter manager Dee Anthony, then overseeing rock heavyweights Humble Pie, Emerson, Lake & Palmer and Joe Cocker. “He came to see us play,” continues Wolf, “and said: ‘You’re a great live band, but I listened to your albums and I’m just not getting it. Why don’t you just do a live record? Just capture what you’re doin’ on stage.’”

In April ’72 the band headed for Detroit, a favoured stronghold, and pitched up for two nights at The Cinderella Ballroom. The result was the kinetic Full House, which featured strutting takes of First I Look At The Purse, Looking For A Love and Otis Rush’s Homework, alongside two-fisted originals Whammer Jammer and Hard Drivin’ Man. The best of the bunch was a monumental version of John Lee Hooker’s Serves You Right To Suffer, a song that folded everything vital about the J. Geils Band – wailing harp, churning organ solos, pungent blues licks and the irrepressible Wolf – into the best part of 10 glorious minutes.

The album may have failed to crack the Billboard Top 50, but it was a huge critical success with a potent presence on underground radio. It remains one of the finest live documents of its era.

If sales at home were minimal, in Europe they were non-existent. Their manager’s decision to send them on the road with another of his charges, ELP, didn’t help.

“They booked a tour of opera houses and we were the opening act,” says Wolf. “Most people had no idea who we were. ELP were more cerebral, whereas we’d come out at 90 miles an hour. They didn’t even know what had hit the stage.”

“We presented ourselves not unlike some of the famous R&B shows,” adds Geils. “The band would come on and do an instrumental, then I’d get on the mike and say: ‘Now ladies and gentleman, our main man: Peter Wolf!’ And Peter would come dancing out and we’d immediately hit on something like First I Look At The Purse.”

Wolf’s charisma didn’t go unnoticed in Hollywood either. In September ’72, he was introduced to actress Faye Dunaway after the band played San Francisco’s Fillmore West. Instantly attracted to one another, their ensuing romance resulted in a Beverley Hills wedding two years later. Although the couple eventually divorced in ’79, citing pressures of work, Dunaway always seemed to keep a flame burning. In her 1995 autobiography, Looking For Gatsby, she wrote: “When I think of Peter Wolf I always remember the Portuguese proverb: ‘Never say you will not drink from that glass again.’” Despite sometimes being lumped with the most inappropriate acts, the band’s reputation began to snowball. Their fourth album, Bloodshot, was their most satisfying studio outing (Wolf describes it as “our greasiest album”). It made the US Top 10, bolstered by the success of Top 30 single Give It To Me.

A couple of patchy releases followed – Ladies Invited and Nightmares… And Other Tales From The Vinyl Jungle – but albums were now secondary to the band’s live status. In January ’75 they filled the famed Boston Garden, returning in November for a taped show issued as double LP Blow Your Face Out. By 1977’s Monkey Island, they were headlining Madison Square Garden. The R&B band from Boston were superstars.

Mention the J. Geils Band today and it elicits a single word: Centerfold. A huge UK hit in 1982, it also gave them their only US No.1. Yet by then they were a whole other beast, their songwriting dominated by keyboard player Seth Justman. Both Centerfold and subsequent hit Freeze Frame were far from their sizzling early years, positing them in the realm of new wave pop. It didn’t last long: Wolf quit the next year after creative tension with Justman. “Yeah, that’s a whole story,” the singer notes wryly. “The next chapter can be called ‘The Great Divide’.”

For a time at least, the band revelled in the success they’d strived so long for. Long-time Geils fans the Rolling Stones took them around Europe on their Still Life tour. In the summer of ’82 they became the first band to play three sell-out nights at the Boston Garden. And there was a triumphant return to Madison Square Garden in New York.

“I felt we deserved it,” says Wolf. “After many hard years of being in debt, doing seven nights a week and driving all night, it was like a collective celebration. It didn’t feel like we were coming in through the back door any more. This one felt like we were walking down the red carpet.”

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 188.