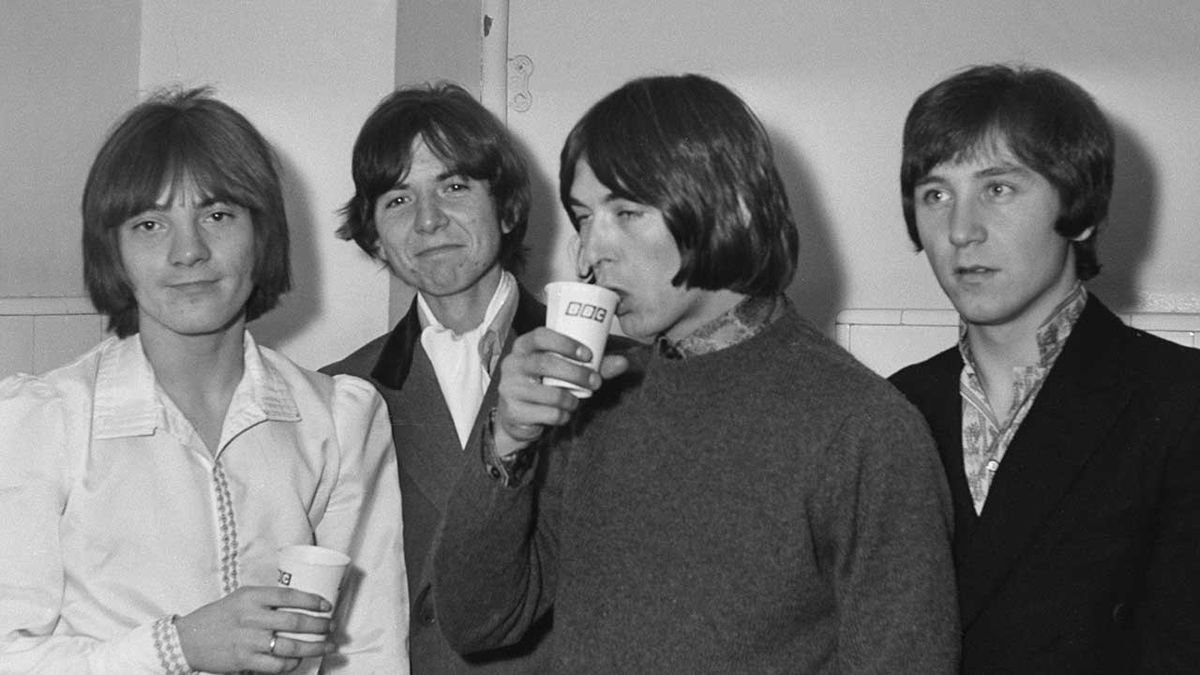

In 1966 The Small Faces were the ultimate embodiment of the metropolitan mod ideal. Four diminutive Jack-the-lads perpetually decked out in razor-sharp threads fresh from Carnaby Street. Rail-thin, hyperactive, mischievous; it was blatantly obvious to every ticket on the street that you didn’t get cheekbones like that from early nights and All-Bran.

Mum-friendly pop stars or not, The Small Faces were clearly quaffing large on whatever chemical indulgences Swinging London swung their way. To alleviate the boredom of a heavy provincial touring schedule, The Small Faces invariably took to the road with as many stimulants as were necessary to render rain-lashed Manchester club dates bearable: at first a little grass or hash; on occasion something a little speedier.

Then, shortly after Steve Marriott (guitar/vocals), Ronnie Lane (bass/vocals) and Ian McLagan (keyboards/vocals) moved into a shared Westminster apartment, a new drug entered their orbit that expanded their artistic remit almost beyond all recognition: LSD.

“We took our first trip in Westmoreland Terrace in early ’66,” remembers Ian McLagan. “And almost immediately started experimenting, using Chinese instruments and all sorts of sounds, to try and recreate a trip.”

By the following year the band’s singles output painted them as full-blown, unashamed drug evangelists. Though interestingly, July ’67’s lyrically blatant Here Comes The Nice concerned scoring speed rather than acid; yet another weapon in the Faces’ extensive pharmaceutical armoury.

“It was weird that they allowed Here Comes The Nice to come out at all,” smiles McLagan. “We were dabbling in all kinds of chemicals and Methedrine was one of them. We were wrong to have written about a speed dealer. They weren’t the nicest people. The guy you bought your hash from was usually just a head, but a speed dealer – like a coke or heroin dealer – was only interested in getting your money. It was quite different. They weren’t your friends.”

Just two months down the line from Here Comes The Nice, The Small Faces delivered one of the Summer Of Love’s defining statements, a psychedelically-inclined slice of quintessentially English whimsicality, characterised by a phasing effect courtesy of Olympic Studios engineer George Chkiantz. With a melody Marriott lifted straight from the hymn God Be In My Head, it concerned a nettle-swathed, rail-side bombsite in Ilford called Itchycoo Park.

Having delivered the East End Good Vibrations, The Small Faces prepared to record the Cockney Sgt. Pepper. But first there was the small matter of an Australian package tour (alongside The Who and Paul Jones) to take care of.

“[The Australian press] gave me hell from the very beginning, because I’d just been busted,” Mac continues, “I was on my way to Athens for a holiday but never got further than Heathrow. As I was showing my passport they smelt the hash on me, searched and busted me. As soon as we landed in Australia we had a press conference, so we’re all lined up in front of the television cameras and the first guy goes: ‘Steve Marriott, Ronnie Lane, Kenney Jones, Ian McLagan… you’re the drug addict right?’”

Controversy continued to plague the tour to its conclusion. “On our way to New Zealand we had to stop off in Sydney. You couldn’t drink on internal flights back then, but one of Paul Jones’ Australian backing band passed a bottle around and the police were called. We weren’t even drinking but they arrested and held us in the first-class lounge where a waitress came straight up to us and said: ‘What would you like to drink?’

"So we drank. The police arrested us as soon as we arrived in New Zealand, but we ended up having a great time. Steve had his 21st birthday party; Keith [Moon] wrecked his room; it was business as usual.”

Some of the material eventually included on their seminal Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake was already in the can by this point, but not enough for an entire album. So in the spring of ’68 The Small Faces hired cabin cruisers and took to the River Thames to write some more.

“We found a camaraderie we hadn’t had before; I was even allowed to be involved in the writing. Long Agos And Worlds Apart was only my second song. It was all about being high. My first song was Up The Wooden Hills To Bedfordshire and that was all about… being high. I think I only had two modes at the time, one was being high and being awake, and the other was being high and being asleep.”

So what, other than the very liberal usage of a cocktail of psychoactive substances, was driving this period of unprecedented creativity? According to McLagan, not the influence of the then blossoming American West Coast psych scene, that’s for sure.

“Most of the music that came out of San Francisco at that time gave me a bad trip,” asserts McLagan. “I thought it was wet; hopeless frankly. It seemed like they’d forgotten the groove, the soul. It was totally boring; we had nothing in common with those guys apart from the drugs.”

There’s no escaping the fact that Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake defines a uniquely Small Faces brand of psychedelia. Above all, it’s very mod, and very English. The cover (a round tobacco tin mock-up), lyrical imagery and subject matter are all symptomatic of the Edwardian nostalgia so prevalent in London as mod went psychedelic. While iconic boutique Granny Takes A Trip dressed the era, Ogdens’… provided its soundtrack: a seamless collage of hallucinogenic blues shouting, pop-art ingenuity, agrarian folk whimsy and music hall chirpiness.

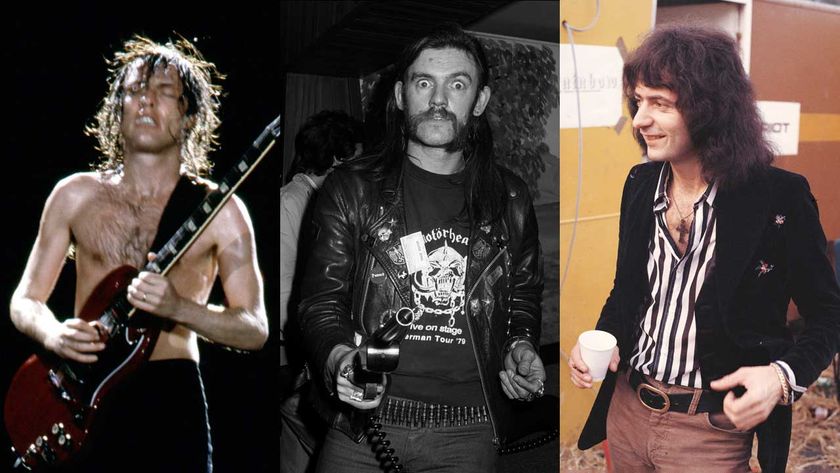

“Coming from the East End the other three had more of a link to the music hall than me,” admits Hounslow-born McLagan, “I’d seen Max Miller, The Crazy Gang when I was a kid, but Steve was a throwback. Apart from being a great blues and soul singer, he was a natural music-hall entertainer and that side was always bursting out of him. It’s a particularly English thing: The Kinks had it, The Who had it. Steve couldn’t help himself, he always had that sense of humour, while we thought we were all blues men, we were Max Miller wearing denim.”

The influence of the music hall on Marriott’s work was never more obvious than on Ogdens’… most celebrated track, Lazy Sunday: “Lyrically, that was all about Steve’s problems with his landladies, landlords and neighbours, which were ongoing,” Mac reveals, “He really was the worst neighbour, with dog shit everywhere and music all hours of the night at full volume.

"And musically, well, while we were on the Australian tour Bob Pridden, The Who’s sound guy – who was a very funny and humorous chap – had this little dance he’d do when we were hanging out that he’d accompany with this little ‘rootdedootdedoo’ tune, which ended up being part of Lazy Sunday.”

Making a feature of one’s cockney accent simply wasn’t done in ’68. Every vocalist in the UK seemed to have been in denial of their natural burr since the initial importation of rock’n’roll from America in the mid-50s, with a mid-Atlantic twang uniformly adopted by all. But Marriott (formerly the 13-year old Artful Dodger in the West End production of Lionel Bart’s Oliver!) not only reclaimed his linguistic heritage on Lazy Sunday.

His rollicking performance on Rene – the bawdy tale of a dockside prostitute – was so strident as to be almost mockney. Here’s the song and performance Damon Albarn plundered for Blur’s career-reanimating Sunday Sunday single. How ironic is it that 1995’s Britpop crown was contested so fiercely by a pair of apparently diametrically opposed bands who were so clearly basing their careers on two different incarnations of the same core band: Blur as The Small Faces and Oasis as the band that would later grow out of them: The Faces.

“I like the fact that people have listened to us and taken something from us,” says Mac, “I’ve heard some of Blur’s stuff and really like it, and I like Oasis, but our biggest champion is Paul Weller. Our biggest champions back then were probably Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood. They told us that Ogdens’… kept them going on their American tours with Jeff Beck. Rod and Woody’s sense of humour is just as mad and rooted in vaudeville as ours."

Further compounding Ogdens’… matters was the other half of the Marriott/Lane songwriting partnership: “Ronnie, on the other hand, was more of a folkie,” McLagan continues, “Song Of A Baker, The Hungry Intruder, Mad John; they all came from him more than Steve. He was already floating in the direction of the folkie he eventually proved to be.”

While Ogdens’… first side was only distinctive for the excellence of its material, the album’s entire second side was given over to a six-part song cycle, mostly written on the Thames, which told the tale of Happiness Stan’s search for the other half of the moon. Hardly grand opera, but in formative concept album terms, this missing link between The Who’s A Quick One While He’s Away and Tommy predated The Pretty Things’ S.F. Sorrow by six months.

“It was Ronnie’s basic idea,” says Mac. ”The story was very thin but we soon made the songs fit. A Quick One was the light: Pete [Townshend’s] little rock opera convinced us that it could be done, so we did one of our own and Pete loved it.”

While the deeply psychedelicised story of Happiness Stan (who lived inside a rainbow in a small Victorian charabanc, by all accounts) was obviously pretty straightforward. After all, what could possibly be confusing about a saga made up of brief musical vignettes concerning grateful flies that band together to form makeshift aircraft, mad tramps, and that concludes with the philosophical assertion that: ‘Life is just a bowl of All-Bran, you wake up every morning and it’s there’?

It was felt that – for the benefit of the slightly less medicated – the services of a clarifying narrator should be engaged. With Marriott’s first choice for the role, ex-Goon Spike Milligan, unavailable ‘Professor’ Stanley Unwin, an unlikely television star of the day (famously fluent in his own particular brand of gibberish known as Unwinese) got the job.

He turned out to be an inspired choice. “I don’t know who suggested Stanley, but boy, what a brilliant stroke,” says Mac. “He came down the studio and we were thrilled to meet him. He’d just hang around while we were going about our business, recording and chatting, and make notes. He picked up on the way we spoke – ‘Cool, man’ and all that – and although it was like a whole new language to him, he totally got it.

"We pointed out what we needed in the way of links and after a while he came back and tried a few things. [producer] Glyn Johns must have trimmed it down a bit because he couldn’t half rabbit on, but he was brilliant.”

A side from the often dizzying mix of musical styles and sound effects etched into its grooves, Ogdens’… was housed in a perfectly circular sleeve based on a vintage ’baccy tin, that was just right for clamping between your knees and rolling a recreational doobie on. The title, meanwhile, came as a byproduct of researching the artwork.

“Ogdens’ tobacco very kindly sent over all these scrapbooks with original labels pasted in,” remembers Mac, “We browsed through them and as soon as Steve saw this rectangular label for Ogdens’ Nut Brown Flake he went: ‘There it is: Nut Gone Flake, perfect.’ Someone copied and adjusted it into a round tin by hand and my pals from art school – Nick Tweddell and Pete Brown – painted the wonderful psychedelic collages inside with all the butterflies.”

Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake topped the UK charts for six weeks in the summer of ’68, with Lazy Sunday stalled at No.2 in the singles charts behind Louis Armstrong’s Wonderful World.

Yet despite outward appearances, all wasn’t wonderful in the world of The Small Faces. Firstly, the band weren’t pleased that Immediate had released Lazy Sunday as a single without their consent. Marriott considered it little more than a novelty song, and certainly not representative of Ogdens’… as a whole. Secondly, while there was pressure on the band to play live, much of Ogdens’… and their more recent singles (Itchycoo Park, Tin Soldier) were almost impossible to replicate outside of the studio.

In February ’69, just a month after The Small Faces’ live US debut, Steve Marriott quit the band.

“We were recording for the next record and things were falling apart bit by bit. Then he left,” says Mac. “It’s a shame because I think we could have made a better album than Ogdens’… We were well on the way to doing it. He and Ronnie were writing beautifully, but we’ll never know.”

So was the Happiness Stan concept a flash in the pan, a passing flirtation with the rock opera format, or perhaps the ex-Artful Dodger had ambitions to branch into musical theatre?

“If The Small Faces had stayed together I think that we probably would have done a whole concept album,” opines Mac. “I don’t think it’s ever been done properly. Tommy is a bit (snores)… long. I know (ex-Small Faces drummer) Kenney (Jones) is keen to animate Ogdens’…, but it needs to be developed and it would be great if someone could write some more songs. I’d be keen to look at developing the second side of the Ogdens’… album into a proper show; a West End or Broadway thing, or maybe a movie.”

Ultimately, though generally accepted to be a high watermark of the English end of the genre, is Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake actually psychedelic?

“No,” Mac states matter-of-factly. “We were over that; we weren’t taking acid when we were making it; you couldn’t get decent acid at that point. The age of acid was very short-lived. It was like the mod thing: mod was two years, max. The clothes weren’t there after a while because the fashion industry caught on and killed it with cheap, crappy imitations.

“Psychedelia was here and gone. For me personally it was that one big night we had in Westmoreland Terrace where I spent five hours or so drawing self portraits on the carpet and having the most wonderful trip. I was thinking: ‘Great, my whole life has changed.’ Then I went to sleep, woke up the next morning, felt a bit odd and then just went back to being ordinary again.”

So while much of Ogdens’… creation was informed by the band’s experiences of LSD, it was very much forged in the afterglow of The Small Faces’ acid experimentation. In fact, at this point the whole notion of a cohesive psychedelic rock scene was little more than a journalistic contrivance to link all the bands together. It was a convenient, generic pigeonhole in which ingenious, progressive music of a certain vintage can be placed.

“The psychedelic scene was about as united as the punk scene,” says Mac. “Punk wasn’t just about one thing and neither was psychedelia. I was always into the blues, rock’n’roll, soul and r’n’b, acid didn’t change that, it was more like an excursion; a left turn before going back on track, and once we’d got over the initial rosy glow of acid it was back to soul music for us, because that’s what we did.”

So, in retrospect, did acid’s influence enable The Small Faces’ to create their defining moment in Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake?

“Ogdens’… was pretty good, it was adventurous, but we could have done a lot better.” Mac concludes, “Acid did change my life temporarily, but as far as the music went, acid was the worst thing that could have happened; because everyone was trying to recreate a trip, which is like trying to catch a cloud."

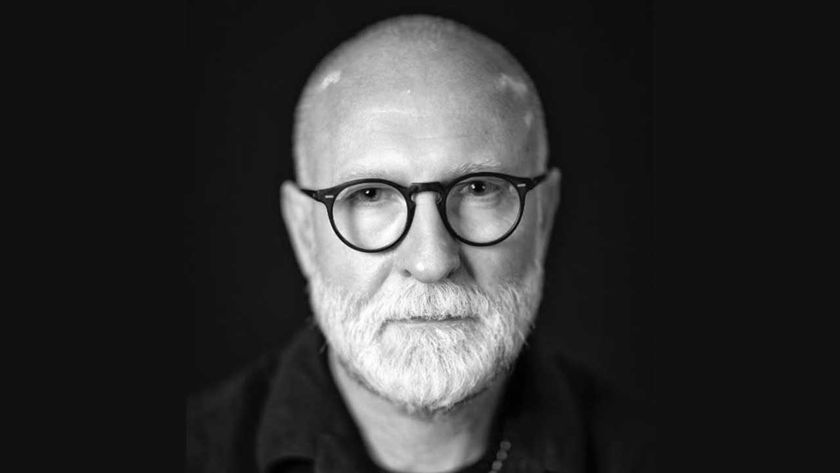

This feature originally appeared in a Classic Rock Psychedelic Special in 2008. Ian McLagan died in 2014.