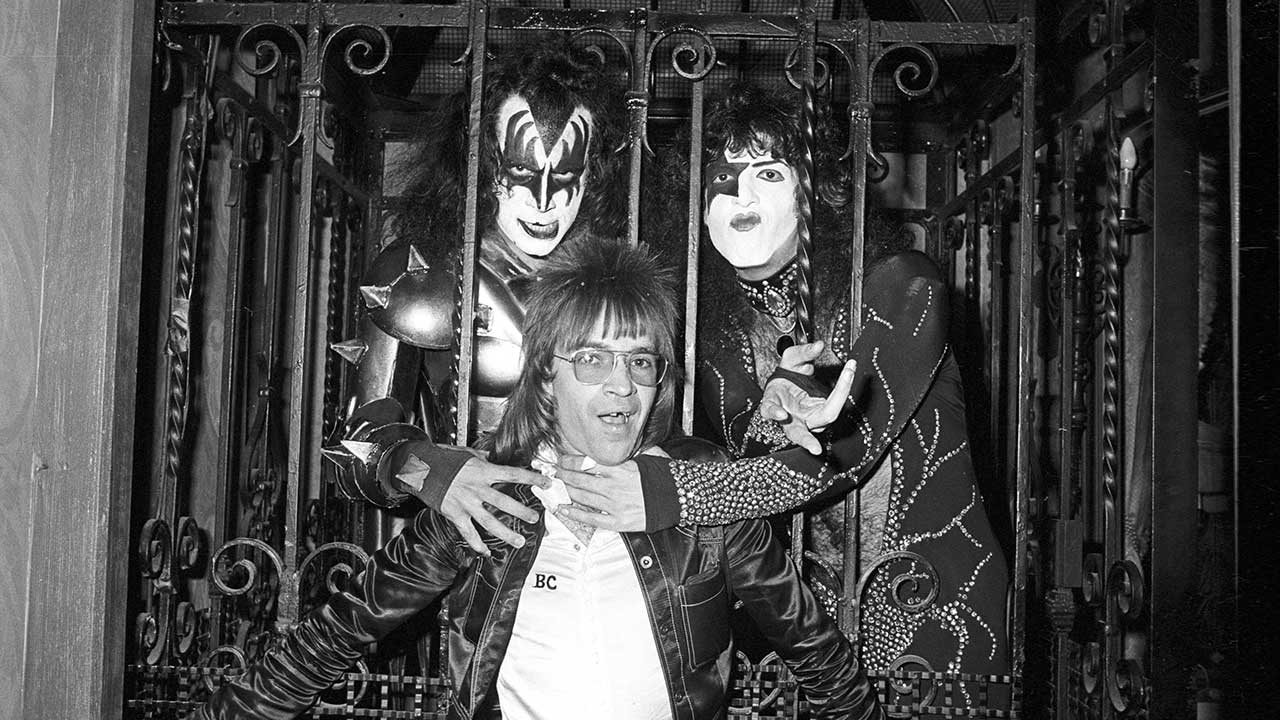

Mayors used to be easy to recognise: the ceremonial robe and three-cornered hat were a couple of clues. If that wasn’t enough, there was always the bling dangling from the neck. You certainly don’t expect to see one wearing black drainpipe trousers, a black jacket and a black shag hairdo.

But then Rodney Bingenheimer is not your typical mayor. He’s Mayor Of The Sunset Strip, that famous and infamous tawdry slither of Hollywood hedonism. That title is an unofficial one (which explains the lax dress code) bestowed upon him years ago and adopted by director George Hickenlooper as the title for his new documentary about Bingenheimer’s extraordinary life.

As a central figure in the Los Angeles music scene for the past 40 years, Bingenheimer has befriended just about every rock star who ever found themselves at the end of Route 66. The walls of his modest apartment are testimony to a lifetime spent in the company of legends. Every inch is adorned with gold records and photographs of the Zelig-esque Bingenheimer alongside the likes of Elvis Presley, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, John Lennon, Andy Warhol… you name them.

The diminutive dignitary might be known only to a few outside of Los Angeles, but there almost everyone with a pulse is aware of ‘Rodney on the ROQ’. Since 1976, Bingenheimer has been a DJ on LA radio station KROQ. As a pioneer of new music, over the years his late-night show has done much to shape America’s musical landscape.

The long list of groups who first got exposure on US radio thanks to Rodney includes The Ramones, The Sex Pistols, Blondie, The Smiths, Nirvana, Coldplay and Oasis.

“I was playing Oasis on a cassette before they were ever signed,” he boasts. “When I was in London, I got it from one of the record companies. They said: ‘It’s this new band, but we don’t think we’re going to sign them’, so they gave me this cassette. It was amazing.”

The word ‘amazing’ is gushed out as though coming from the mouth of some awestruck teen. Bingenheimer retains a youthful sense of wonder. His excitement about the latest band is akin to a kid with a new toy. His tiny frame, boyish looks and unassuming manner are hard to reconcile with his iconic status. Cripplingly shy, with a reluctant line in dialogue, the wonder is how he keeps such exalted company as he has done for four decades. “I don’t know. I’m quiet. I don’t bug people. I don’t hang out or hang on to them.”

Cher, who with Sonny Bono became like surrogate parents to the young Rodney, has said of him: “He’s very genuine. You don’t have to worry about an ulterior motive."

After moving with his mother from his Northern California home town of Mountain View, the young Bingenheimer immersed himself in the LA scene. With The Beach Boys and The Doors putting the city in the eye of the Swinging 60s storm, every night was a party – and at every party was Rodney.

For all his reticence when it came to meeting women, hanging out with celebrities certainly didn’t harm his cause. Nor did the fact that he was once hired as Davy Jones’s stand-in after Bingenheimer failed an audition to join The Monkees. Robert Plant was quoted as saying Bingenheimer got more girls than he did, and in the documentary Mick Jagger refers to him as a “famous groupie”.

It’s not a term Bingenheimer embraces. In fact he doesn’t like to think of himself as a famous anything. He prefers to see himself as “the designated driver between the famous and not so famous”. And in that capacity, his life has been quite a ride.

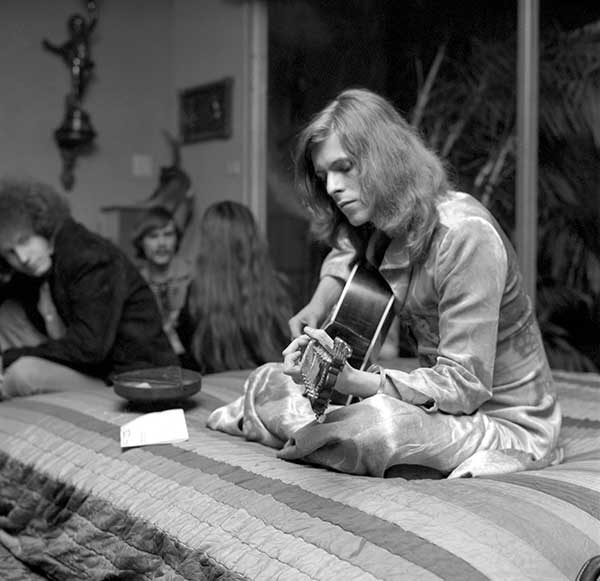

At one time his role of driver was literally that: “My job was to take David Bowie around to the radio stations and get him played.”

At the time, Bingenheimer was working at Mercury Records, and few in the US had ever heard of the young English singer. “I picked him up at the airport and had him stay at my friend Tom Ayres’s house.”

When the The Man Who Sold The World-era Bowie sauntered through customs he made quite an impression on waiting chauffeur Rodney. "Well, I thought, ‘this is quite different’,” Bingenheimer laughs at the memory. “The guy’s wearing a dress, he has a cap, a long purse and long hair.”

Since their first meeting, Bingenheimer and Bowie remained close. Rodney is credited with helping Bowie secure a US recording contract. Bowie returned the favour when he suggested to Bingenheimer he turn his love of glam rock into an LA club. And so began, in 1972, Rodney’s English Disco.

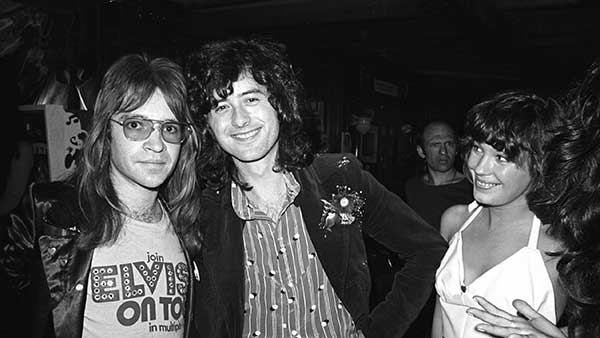

With family roots in South Shields, Bingenheimer was a self-confessed Anglophile obsessed with everything that glittered in music. His English Disco, located in a small shopfront on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip, soon sparkled to the sounds of the likes of T. Rex, Slade, The Sweet and Roxy Music and became the place to hang out. The list of stars who dropped by reads like a Who’s Who of rock: “Led Zeppelin, Marc Bolan, Suzi Quatro, New York Dolls. I did a party for Suzi Quatro and a party for T.Rex. Iggy Pop would always be there and actually played at the club.”

On other nights, the likes of Warhol, Bowie, Elton John or Lou Reed might be found on the VIP side of the velvet rope separating the deities at the club from the worshippers.

One evening, the man anointed the King of Los Angeles Radio played host to the King of Rock’n’Roll when Elvis Presley showed up: “I’d send out pitchers of English beer – Watney’s on tap – to RCA and he liked it. He said he hadn’t had English beer since he was in Germany. Then one time he came to my club with [stepbrother] Rick Stanley and his girlfriend and bodyguards. I was playing Suzi Quatro’s All Shook Up: and his girlfriend said: ‘You do that better, Elvis’.”

At heart, Bingenheimer is a fan. A huge fan. And one who was lucky enough to turn his adulation into a career. It comes across in the way he drops names and talks about people, and it’s never more evident than when he’s talking about meeting Presley: “It was like God or something. The whole room lit up. It was really weird. He had a presence. You know he’s in the room.”

Rodney describes Presley as “a real sweet person. Very funny. He was really nice,” and recalls attending a party in Las Vegas with him when “he introduced me to Frank Sinatra”.

One of the most prized possessions in Rodney’s extensive memorabilia collection is Presley’s driving licence.

‘Sweet’ and ‘nice’ are words bandied about frequently by the quietly spoken Bingenheimer, who, perhaps surprisingly, doesn’t haven’t a bad word to say about anyone. And if he did, he wouldn’t utter it in public – which is the reason a proposed biography was scrapped. Following Rodney’s refusal to oblige a publisher’s request to dish the dirt on his celebrity friends, the book idea was abandoned in favour of the documentary.

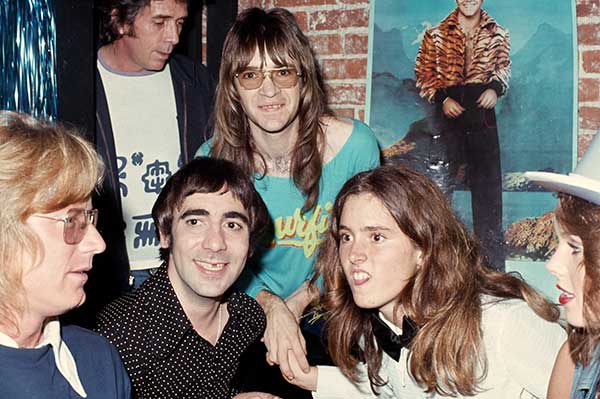

Perhaps the closest he comes to telling a scandalous story involves The Who’s hellraising drummer: “Keith Moon came to my club once in a Gestapo uniform. I was closing up the club and he wanted to go get something to eat. So we went to Canters Deli on Fairfax – it’s like the Jewish deli. So we went there, and he was wearing a Gestapo uniform! Shocked a lot of people. He was wild.”

The vision of Bingenheimer sipping matzo ball soup with a Nazi-attired Keith Moon is as unlikely as it is indelible. He seems to have a wealth of such stories. They don’t exactly roll off the tongue, but if you throw him a name and pull, they come pouring out.

Jimi Hendrix: “I saw his first show. I was walking down Sunset Boulevard with Chas Chandler [Hendrix’s manager], and he said: ‘I’ve got this new artist you gotta see. He’s playing the Whisky A Go-Go.’ So he got to me into the Whisky.”

One thing Rodney prides himself on is his eye for talent – “I have a vision of what’s going to be the next big thing”. It’s why so many bands are in his debt. It’s a gift he’s always had, and why, he says, he knew instantly that Hendrix was “going to do something. He was really going to change the world, especially musically.”

When John Lennon’s name is brought up, Bingenheimer recounts the time he was covering the 1969 Rock’n’Roll Revival festival in Toronto for his It’s All Happening column in Go magazine. The bill included The Doors, Alice Cooper, Gene Vincent and The Plastic Ono Band, all of whom he knew personally. “The guy who did the concert sent me out in a limo to pick up John and Yoko from the airport.”

Shortly after, Rodney found himself introducing the ex-Beatle to his long-time hero Gene Vincent. “He was really jazzed about that. John asked Gene for his autograph, and Gene asked John for his autograph.”

A witness to numerous musically historic occasions, the proud owner of a stash of gold records and artifacts from appreciative artists, a DJ on one of the biggest radio stations in America… Many might consider Bingenheimer’s life a success. But in one of the more poignant moments of Mayor Of The Sunset Strip, director Hickenlooper asks him if he wished his life had been different.

After a pause Bingenheimer mumbles: “Yes”. It is a telling confession from someone who never likes to dwell on anything negative and has spent a lifetime devoted to the pursuit of happiness. It’s what first attracted him to music. “It was just this happy, happy sound.”

Bingenheimer, the only child of a marriage that ended when he was three, would hole up in his room, excited and mesmerised by the glamour and joy promised by the sleeves of the Cameo Parkway label and artists such as Bobby Rydell and Dee Dee Sharpe. His quest for happiness has taken him on a remarkable journey. But it’s difficult not to feel that true happiness has somehow eluded him, although he’s quick to deny it.

When asked if he considers himself a happy person, he replies: “Oh yes, yes. I’ve always had the best life. I’ve always had the best-looking women, the best music and the best knowledge of what was happening. I don’t know how that could be unhappy.”

Anyone watching Mayor Of The Sunset Strip, however, is likely to come away with a distinctly different impression. The documentary portrays Bingenheimer today as a somewhat sad and lonely figure. His glory years and womanising behind him, he still clings to the hope of finding “that right girl”. But in LA, a city obsessed with youth and wealth, neither of which he possesses, it’s difficult. “I’ve been on dates where they actually say: ‘I can’t see you any more because you’re older’.”

Asked how he would have liked life to have been different, he replies: “I can’t really define that.”

On whether perhaps all that partying had got in the way of him doing more with his life, he concedes: “Maybe.”

Does he wish he had achieved more? “Yes.”

In what way? “Did more things than just my once-a-week radio show.”

He cites doing more writing or “something in management or involved with record companies”. There might have been the hope that after six years in the making, the documentary would have changed Bingenheimer’s fortunes, but apparently it hasn’t: “No, everything’s exactly the same. Nothing’s changed.”

Would he have liked it to have changed things? “Yes.”

But who doesn’t have regrets? At least Bingenheimer got to fulfil his childhood dream. “I always wanted to be a disc jockey. I used to lay in bed at night hearing the DJs on the radio playing the hits.” His passion for his profession has never waned, even if he still treasures the music of those long-faded disco days.

“It was magic,” he says. “Now the magic has gone. That’s why I’ve got my show, to try and revive the magic.”

And it’s tough to feel sorry for someone who spends his time hanging out with the likes of Paul McCartney, Gwen Stefani Brian Wilson. “I talk to Brian every day. He comes to my house.”

The two men often go to Canters Deli (although presumably neither of them wears a Gestapo uniform these days) and chat about a certain 60s vocal combo. “All Brian talks about are The Ronettes.”

Still, Rodney’s there, as he’s always been, to hear it first-hand.

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 82, in June 2005.