It might have had a powerful hook and a monumental groove, but Making Plans For Nigel was not an obvious chart contender. In fact, with its cavernous drums, jagged guitar riff and nagging melody it was like some mutant hybrid of dub reggae, post-punk and chirpy pop. And yet it became Swindon band XTC’s first Top 20 hit.

But it didn’t start off as a skanking nursery rhyme. When it was first presented to the others by bassist Colin Moulding, not the group’s regular writer, it was rather less shudderingly propulsive.

“It sounded like the Spinners,” laughs Andy Partridge, XTC’s chief songwriter. “When Colin brought it to us and played it on an acoustic guitar, he might as well have had a dress on and some horn-rimmed glasses like Nana Mouskouri.”

For the aspiring songwriter it was tough having to prove himself in public. “It was like what George Harrison said,” Moulding notes. “‘John and Paul were able to get their rubbishy songs out of the way before The Beatles became famous, whereas I had to do it in the public eye.’ On some of my early stuff I was aping Andy a bit too much. This was me trying to write something more ‘me’.”

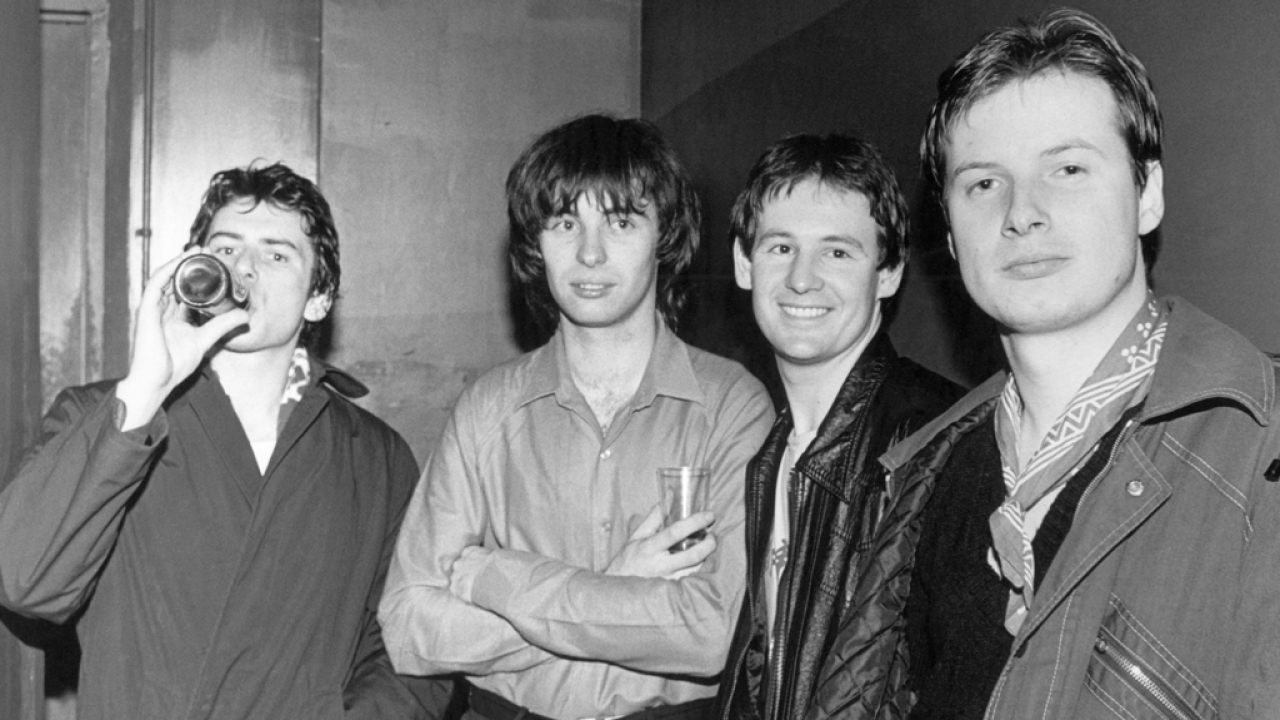

A song about a boy being pushed by his middle-class parents into a life of crushing work tedium, Making Plans… reflected a real dread among the band members, who, as Partridge puts it, were “four kids off a council estate”.

“I remember going with the school around this factory,” Partridge groans, “traipsing round these work benches and production lines. It felt so angry in there. One bloke looked up at me in my school uniform and said [low, grumbling voice]: ‘You don’t wanna fucking work here, mate,’ like one of the people suffering in one of the circles of hell.”

The titular name was another trace of their school days. “There were Nigels about,” explains Moulding. “Some of them were quiet types. Bullied, perhaps. I guess I was writing a song for the bullied.”

As for why he chose a nationalised industry for the lyric, British Steel was in the air at the time. “You couldn’t get away from all the industrial disputes, the three-day weeks and all that,” he reflects, recalling that said organisation’s union official got on the blower when they heard the track, wanting him to “join the cause”. “British Steel seemed to fit right in.”

Making Plans For Nigel had an appropriately metallic tone, a dub-spacious one. It was a transitional record, and a mark of what could be achieved with XTC’s new two-guitar line-up (guitarist Dave Gregory had recently been brought in as a replacement for keyboardist Barry Andrews). “It was like: ‘Let’s see if we can do something new with this rather tired format that had been bored to death by people like Wishbone Ash.’”

It freed up XTC rhythmically. They had already experimented with dub on their second album, Go 2. In charge of sonics this time, at the newly built Townhouse Studios in London, were Partridge, drummer Terry Chambers, producer Steve Lillywhite and engineer Hugh Padgham. And they found an unlikely source for the dubby effects: “Don’t laugh, but I’d been listening to David Essex’s Rock On,” Partridge says of the teen heartthrob’s bizarre 1974 smash hit. “I’d never heard anything so echoey, empty and dreamlike. As soon as I had access to a mixing desk it was like: ‘Ah, that’s what you can do: put in loads of reverb!’”

The striking drum pattern was influenced by Devo, XTC’s Stateside oppos in the rhythmically twitchy stakes. “Andy was forever torturing Terry to come up with more weird and wonderful rhythms,” says Moulding. And as for its brute force, Moulding says: “We may look like a load of wimps, but we were pretty impressive when we got going.”

“It’s the thrill of the mechanical,” Partridge continues. “Later, people would tell us we sounded like The Beatles. But at this point we were more concerned with sounding savagely original.”

‘Savagely original’ had been XTC’s concern from the off. When they formed, in the proggy mid-70s as the Helium Kidz, Partridge insisted they get their hair shorn and wear boiler suits to achieve his desired “mechanics on a space station” look. He also had a ‘short, sharp songs and no solos’ policy. “I wanted us to look forward,” he says. “Something different to the previous generation.”

After changing their name to XTC, in 1978 they released White Music and Go 2, two albums of tense, nervous oddities. On the first of those two, the quirkily rhythmic Statue Of Liberty and This Is Pop confirmed XTC as brainiac Brit cousins of Talking Heads and won them acclaim as the idiosyncratic, intelligent wing of punk. It wasn’t until third album Drums And Wires that the band became a serious critical force. And with Making Plans… they became a commercial one too.

Moulding remembers the sessions for that track for their “terrific camaraderie. We had lots of laughs.” But how did Partridge feel about his ‘underling’ writing what remains XTC’s biggest hit to date? “How would anyone feel when one is the principal songwriter in the band and along comes this upstart and spoils everything?” Moulding replies. “I think he took it as best he could. I did feel a bit of a cold chill from the others with all the attention that I was getting. And I felt a bit of a fraud. But on the other hand I was totally intoxicated with it all. I think I drank the wine too fast; others might say I savoured it a little too much. In my defence I can only say that I was young and eager for experience. Andy said I turned into a Caligula-type figure for a brief period. Caligula? Never. Claudius, maybe.”

“He started acting differently,” Partridge suggests. “He got a bit imperious. He even moved into a flat with our manager. We thought: ‘Fucking hell, this has gone to his head.’ But he calmed down after a bit.”

The nuclear drums on Making Plans… seemed to usher in the 80s (the Lillywhite/Padgham team later worked on records by Phil Collins and Peter Gabriel). The song also paved the way for a successful decade for XTC, with albums such as English Settlement, Mummer, the Todd Rundgren-produced Skylarking and the psych-y Oranges & Lemons. Their last album is 2000’s Wasp Star (Apple Venus Volume 2).

According to Partridge, it was Making Plans For Nigel that “helped jemmy the door open for us and public acceptance”. For Moulding it was proof that the esoteric and strange could be widely embraced. He has been particularly pleased by the way the song has seeped into the national consciousness. “In a way that means more to me than anything,” he says. “There’s not a week goes by without it being associated with some Nigel or another. I see Nigel Farage is getting the ‘making plans’ treatment just lately.”

Not that it has proved his passport to the glamorous life. “The first thing I bought with my royalty cheque was a pine wardrobe – there’s glamour for you,” he chuckles. “I haven’t set sail for Monte Carlo yet.”