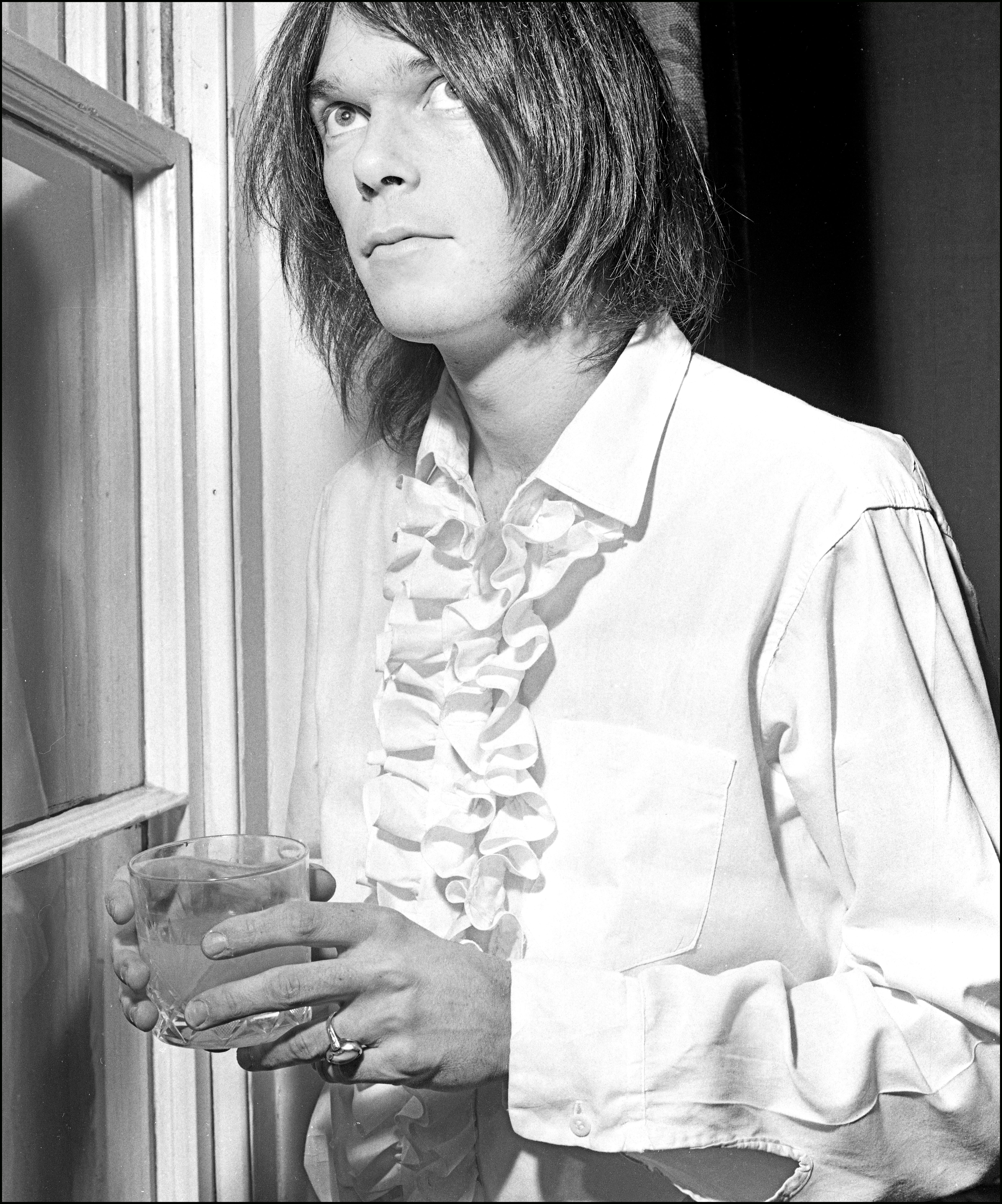

Neil Young’s most mysterious song has its beginnings in the wilds of Peru in 1969, where an out-of-control Dennis Hopper was directing The Last Movie, his follow-up to Easy Rider. With Hopper was his friend Dean Stockwell, a minor child and teen star of the 1940s and 50s, later famous for the 90s time-travel TV hit Quantum Leap.

“In Peru, Dennis very strongly urged me to write a screenplay,” Stockwell recalls, “and he would get it produced. I came back home to Topanga Canyon [in the mountains outside LA] and wrote After The Gold Rush. Neil was living in Topanga then too, and a copy of it somehow got to him. He had had writer’s block for months, and his record company was after him. And after he read this screenplay, he wrote the After The Gold Rush album in three weeks.”

Stockwell’s screenplay is long lost. Young’s biographer Jimmy McDonough was told that it was “an end-of-the-world movie”, which ended with a tidal wave crashing towards its hero as he stood in the parking lot of the Topanga hippies’ favourite hang-out, the Corral, whose regulars included Young and Joni Mitchell. Stockwell’s friend Russ Tamblyn was set to play a rocker recluse living in a castle, and wild-haired local artist George Herms was meant to haul a “tree of life”, like Christ with his crucifix, across the Canyon.

“It’s not a linear, regular storytelling kind of film,” Stockwell explains. “Really what was in my mind was that the gold rush in effect created California. And the film took place on the day California was supposed to go into the ocean. So that’s what happened after the gold rush.”

“I read the screenplay and kept it around for a while,” Young wrote in his 2012 autobiography Waging Heavy Peace. “I was writing a lot of songs at the time, and some of them seemed like they would fit right in with the story.”

Stockwell brought producers from the company Hopper was contracted to, Universal, to Topanga, introducing them to potential local cast-members such as Janis Joplin, and Young, who was keen to write the soundtrack. But the execs were having enough trouble with Hopper, and ran a mile from the chaotic hippie utopia.

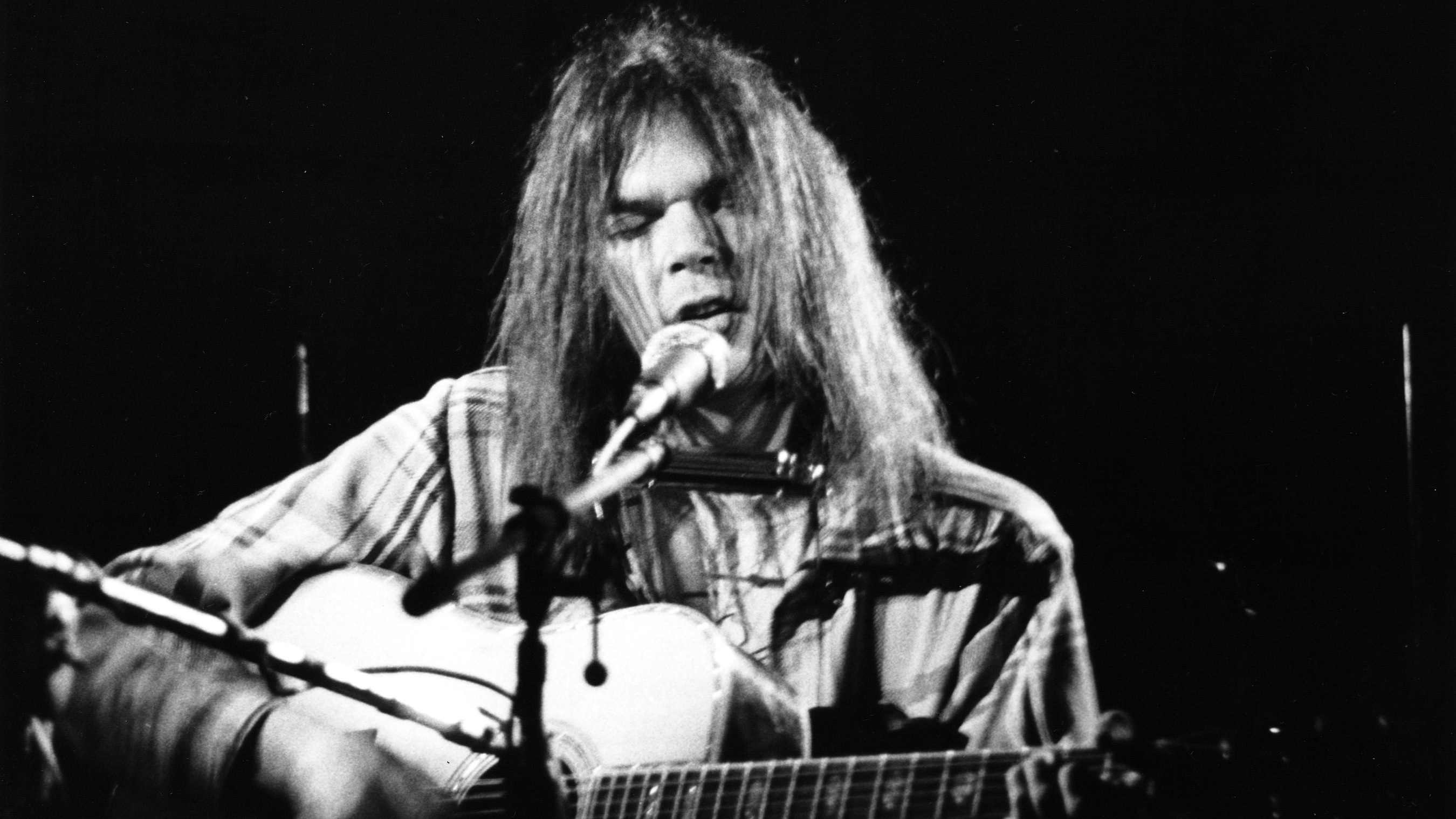

Undeterred, Young went ahead with the music. The After The Gold Rush album was recorded between legs of Crosby, Stills Nash & Young’s massive 1970 US tour, and immediately after Young’s shows that March with the grungier Crazy Horse. After early sessions in Hollywood’s Sunset Studios, most of it was recorded in the lead-lined basement of his house in the Canyon. There was barely space in the cramped room for CSN&Y bassist Greg Reeves, Crazy Horse drummer Ralph Molina, Young and his newest recruit, teenage guitarist Nils Lofgren.

“I was an eighteen-year-old who was with these twenty-three, twenty-four-year-old people, and it was all overwhelming to me,” Lofgren recalls. “I was the kid who tagged along. We did it in this little studio, with a little side control room that [producer] David Briggs managed the sound on, with a remote truck out in the driveway. Neil didn’t mind rehearsing a bit, but we didn’t belabour stuff.”

Southern Man would become After The Gold Rush’s most infamous song after Lynyrd wrote Sweet Home Alabama in response to it. But the album’s true centrepiece was its title track. Young sings alone at the piano for its first two minutes, after which he’s joined by session player Bill Peterson’s mournful flugelhorn.

Its three verses set out contrasting scenes. The first is a medieval panorama of knights and peasants. In the deeply evocative second, Young is ‘lying in a burned-out basement’ when the sun suddenly rips through the night. ‘There was a band playing in my head,’ Young responds wearily, ‘and I felt like getting high.’ In the final verse those chosen take humanity’s ‘silver seed’ into space while others are left behind, as the world dies.

“The song was written to go along with the story [of the film],” Young reflected in Waging Heavy Peace, “and the main character, as he carried the Tree of Life through Topanga Canyon to the ocean.”

“It relates to the screenplay in an artistic way, not directly, in dialogue or anything,” says Stockwell, who Young invited to watch the sessions. “That’s how he found himself in it, which coincided beautifully with what I had in mind. Neil’s rush of writing then has something to do with the film – with the exception of Southern Man. If you could calculate the amount of human energy that goes into the making of one of his songs, you would have a really fucking high number, man.”

“Neil never told me what the song was about,” Lofgren says. “I’d love to bend his ear about it. It’s like it’s all our own fantasies, as we hear the words. But look, man, I was standing there in the control room, looking through the glass watching him play that thing on the old upright piano, and it’s still on the road with him. We took it on the Trans tour and I got to play it a lot, and at some of the Bridge School benefits too. It’s a very historic piano, certainly in my life.”

- Q&A: Neil Young

- Q&A: Stephen Stills

- Technology: Neil Young

- It's Prog Jim But Not As We Know It: David Crosby

“After The Gold Rush is an environmental song,” Young said, trying to finally nail its meaning for McDonough. “I recognise in it now this thread that goes through a lotta my songs that’s this time-travel thing… When I look out the window, the first thing that comes to my mind is the way this place looked a hundred years ago.”

Rolling Stone ripped the album apart at the time of its release in 1970. But it would be the first of Young’s solo albums to hit the US Top 10, paving the way for its chart-topping follow-up, Harvest.

“And even then, though I had the album,” Stockwell reflects ruefully, “I still couldn’t get that screenplay produced.”