It was the big reveal: the moment when the monster suddenly – shockingly – becomes human. For Alice Cooper fans, that moment came in 1975 with the release of the singer’s first solo album, Welcome To My Nightmare. A fantastical piece of work that would become emblematic of everything Alice would represent over the coming decades: strange but no longer scary; weird but no longer mean; naughty but really quite nice.

Overnight, Alice Cooper the ghoul-eyed, sexually depraved dissector of baby dolls, friend only to live snakes and dead chickens, had transmogrified into something else. A victim, in fact – no longer living the crazy dream, but trapped inside his own unending nightmare. And it was into this nightmare that he now invited us, the audience to join him – to bear witness, at least, to the battle he was now embarked on against the bedraggled fiend he had created, and from which he now so desperately wished to escape.

“Everybody expects me to be the Alice I am onstage,” he said at the time. “But they have to understand that Alice is just a character I play... I have no message at all. I never did.”

Or rather, the message had changed. It was no longer about nihilism – getting Elected so you could declare School’s Out; the No More Mr. Nice Guy who would throw you Under My Wheels as soon as look at you with his cadaver eyes. For Alice, the second half of the 1970s – the second half of his life – would be about laying down the welcome mat, however blood- spattered and ragged; becoming part of the family, however dysfunctional that family was.

For someone who had become famous for frightening the little girls with his uniquely brutish form of androgyny, for singing songs like Dead Babies and being publicly executed onstage every night, this was truly shocking stuff.

Not least for the remaining members of the original Alice Cooper band, who now willingly exited the stage. “The band never dreamed that the personality of Alice could become bigger than them,” the singer later recalled in his autobiography Me, Alice. “We were all making unbelievable amounts of money, but it didn’t make it up to them in ego.” Instead, Alice wrote, the band members “began to have the same exact fights we had when we were poor, except ‘That’s my tomato you’re eating’ turned into, ‘That’s my Rolls, get your ass out of it’.”

As a result, the Alice Cooper band’s final album together, Muscle Of Love, in 1973, had been a prosaic, muso-driven affair, and consequently less successful than its predecessor, Billion Dollar Babies. By now, both Neal Smith and Michael Bruce were exploring solo projects. For his own first solo album, Alice set out to ramp up the theatricality, while taking the music to a whole new level of professionalism and panache.

Crucial in this latter respect was Alice’s reconciliation with producer Bob Ezrin. Ezrin had overseen the four best Alice Cooper band albums, co-writing several key tracks, but had bowed out before Muscle Of Love, sensing resistance from certain band members who wanted to wrest power back from him. Now, for Welcome To My Nightmare, he was back.

Given free rein to assemble his own band, Ezrin brought in Lou Reed’s backing group. Headed by the twin guitars of Dick Wagner and Steve Hunter, this was the same blisteringly hot line-up that had recorded Reed’s live Rock’n’Roll Animal album.

Ezrin says, “On Welcome To My Nightmare, I was actually working with a group of people that I had worked on other stuff with – I made a band and brought them all to Toronto and made that album, fairly quickly.” The band members were, he recalls, “all really into the process, and every single day was exciting.”

The album was recorded over three months at Toronto’s Soundstage studio, followed by stints at New York’s Record Plant East, Electric Lady and A&R Studios. The concept for the album, Ezrin recalls, came from a movie idea he and Alice had been discussing, “which was about this guy, Steven, and the general theme of it was that this guy is a rock star and he’s having an affair with somebody. They’re going skiing in his private plane, there’s an accident. They are buried under the snow and when they are eventually found, there is only him. From that point on, he is transformed, and by night he craves flesh.

“So we had this little thing our minds that Steven was having a problem differentiating between reality and imagination, that started the whole thought about the nightmare – and that’s where we looked at each other and went ‘Hey, that’s great’. And then Alice came up with the idea, we could do a movie, but let’s do this great stage show. Let’s do this whole thing about this guy Steven, and let’s make it his nightmare.”

Though the movie was never made, one of the directors they discussed it with, Daniel Mann, introduced them to legendary horror-movie actor Vincent Price on the set of Mann’s 1975 movie, Journey Into Fear. It was at this meeting, “united by Monte Cristo cigars,” that Ezrin half-jokingly asked Price, “How would you like to make your rock’n’roll debut?” Bemused, Price looked at him and said, “Really, do you think I ought to?” Ezrin told him, “I think you’d be a total rock star.” To which Price replied simply: “Let me know where and when.”

When, months later, the singer and producer were sewing ideas together for Welcome To My Nightmare using some of the music they’d originally intended for their now aborted movie – including a track called The Black Widow – Ezrin suggested they call on Price to provide a spooky narrative intro.

It was a masterstroke. For Price, had he not been born to an earlier age, would have made a convincing rock overlord. While Alice, brought up on TV late-night monster movies, saw himself as the Bela Lugosi of rock. Not only did the two Vincents sound great together on record – so much so that years later, Michael Jackson was inspired to call on Price to perform a similar role on Thriller – they also shared the same pragmatic, arm’s-length attitude towards their respective onstage personas.

“We were waiting for [Price] to come into the studio and expecting him to be dressed all in black,” Alice later recalled. “He comes in and he’s wearing a Hawaiian shirt and purple striped pants. Everyone is going ‘That’s Vincent Price?’ Then he goes in and he does this really Edwardian dramatic reading, and it scares the hell out of you. Then you look at him and you just have to start laughing, because he looks like Ronald McDonald. I really get along with him – we are very good friends.”

The rest of the album was similarly inspired. With Ezrin leading the way not just as producer but also as co-writer and keyboardist on several tracks, and Dick Wagner also sharing writing duties, there was something for everyone. There was the swaggering guitar-flash of Escape – ‘There’s no place to go/Just put on my make-up and get me to the show’ – and the arm-waving Department Of Youth, Alice’s best anthem since School’s Out, replete with demented kiddie choir, and a lovely touch of black humour on the fade as Alice asks “Who’s got the power?” and the kids answer: “We have!” Alice: “Who gave it to you?” Kids: “Donny Osmond!”

Older Alice fans could revel in tracks like the creepy Cold Ethyl, which recalled the necrophilia of I Love The Dead from Billion Dollar Babies, but with its creepy keyboards replaced by kickass rock, courtesy of the blazing trails left by Wagner’s and Hunter’s duelling guitars. Similarly The Awakening, which referred all the way back to Killer; and the absolutely stupendous title track, which contained all the delicious chills of classic Alice, but delivered with the kind of curtain-raising pomp only a group as consummately skilled as this was capable of. Ezrin piled on the keyboards, synths and horns without detracting one fiery iota from the sheer force of the drums and guitars.

Best and most unexpected of all was Only Women Bleed. Lambasted at the time for feminist-baiting lines like, ‘Man got his woman/To take his seed/He got the power/Oh, she got the need’, Only Women Bleed was actually one of the most insightful, genuinely heartfelt rock songs in defence of womankind ever recorded up to that point.

The story of a woman in an abusive relationship, its moving refrain, ‘She cries alone at night too often/He drinks and smokes and don’t come home at all’ belied whatever cheap gag might have been implied by the title. Ezrin outdid himself, working with Al Macmillan to supply a string and horn arrangement that made the song at once sweetly irresistible and wincingly painful.

Or as Alice put it: “Only Women Bleed sounds like it could be scary, but it’s not. I always wanted to write a love ballad, and Only Women Bleed turned out to be it.”

Unlike any track before, Only Women Bleed proved there really was a human face behind the scary mask. It would also provide Alice with his first big solo hit when it was released as a single ahead of the album. Since then it has been covered by a number of significant female artists, including Tori Amos, Lita Ford, Etta James, and Julie Covington, to name a very few.

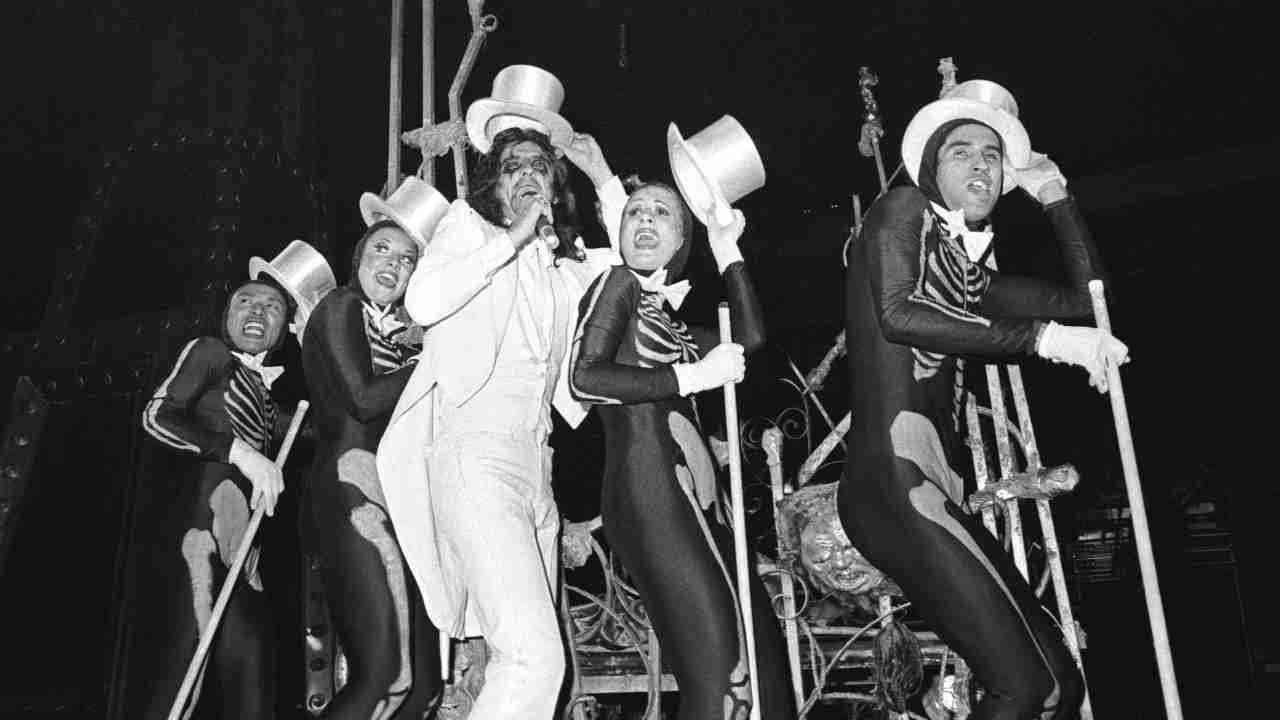

Generally, though, the theme of Welcome To My Nightmare was one of fun; of unashamed entertainment; of thrills and spills and loves and laughs in equal measure. These are the aspects that the cover, featuring Alice in top hat and morning suit with white bow tie, emphasised – and these are the aspects that would become even more apparent with the spectacular new stage show he was to take on the road. At the time, this was the biggest rock tour ever, eventually netting over $9 million – an unheard-of sum in the mid-70s.

Even in an era that excelled in over-the-top stage production – witness the post-apocalyptic cityscapes of Bowie’s Diamond Dogs show, Elton John’s outlandish Liberace-of-rock stage-sets or the elaborate costumes featured in the Genesis The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway show – the 1975 Welcome To My Nightmare tour was exceptional. The stage production alone would cost over $400,000, with choreography by David Winters, the English-born dancer who had appeared in the original 1957 production of West Side Story.

“I don’t really care whether the thing comes off commercially,” Alice claimed at the time, “as long as it’s entertaining. There’s going to be things in the stage act that kids have never seen before.”

There certainly were. At the very end of the 65-date US leg, in Lake Tahoe, Vincent Price played his part live onstage. “He was like a little kid,” remembered Alice. “He had so much fun doing it.”

Though for the rest of the tour, it was only Price’s recorded voice that featured, it was clear this was no mere rock show. It began each night with Alice emerging on a bed from billowing clouds of dry-ice, singing Welcome To My Nightmare, the band hidden away in the background shadows. Then he burst into the first familiar highlight of the evening, No More Mr. Nice Guy, with Alice flanked by the Cherry Sisters – Robin and Sheryl, the dancers who had earned their nickname by refusing to allow anybody on the tour to sleep with them. This would abruptly change when Sheryl, a former ballerina, began a relationship with Alice that later resulted in their marriage.

From there it was one slick theatrical set-piece after another, Alice using the monster toy chest at the side of the stage to rummage through for further props, including the soon-to-be-infamous life-sized ‘doll’ named Cold Ethyl, as the barely visible band roared away furiously behind him. During another new number, Some Folks, the dancers, clad in skeleton costumes, posed in a variety of sex positions, before being joined by Alice, in white top hat and tails.

In Cold Ethyl, the singer threw his lifeless doll across the stage, delighting in her “refrigerator kiss.” During Only Women Bleed, the doll was replaced by a real-life Cherry Sister, dishevelled and bloody, tracing the song’s arc with her body as Alice crooned like a sheep-killing dog. He would get his comeuppance, though, with the appearance near the climax of a nine-foot furry cyclops who would brutalise Alice by tossing him about the stage like one of his dolls.

Every minute of stage-time was planned to the last second, from the giant spider’s web that shrouded the stage during The Black Widow to the misty cemetery at the end with the neon gravestone reading: ‘Alice Cooper 1948 - ’ before, as Alice put it, “all the nightmarish creatures follow me out onto the stage where we do a rock’n’roll Busby Berkeley dance number.”

Predictably, rock critics questioned the ‘validity’ of the new show, comparing it unfavourably to the blood-and-guts spontaneity of old. The people for whom the new show was designed, on the other hand – the fans – loved every scripted minute.

“I will admit that this new show is pretty calculated,” said Alice at the time. “But you can’t do a Broadway or Vegas show without it being calculated. And it is cold. It does freeze the audience out to a certain point... It’s Alice, the attitude is still there, but it’s more cerebral. I got out of the fact of trying to say anything except ‘This is showbiz’.”

Alice’s showbiz life now extended beyond the stage, too. Not content with appearing on TV shows like Hollywood Squares – a counterintuitive move that prefigured his later exploits on The Muppet Show – Alice also devised his own Welcome To My Nightmare TV special, co-starring Price.

Titled simply Alice Cooper: The Nightmare, it aired on US prime-time TV in April 1975 while Alice was mid-tour, it was essentially the live show, refined and expanded for television. Viewed now on YouTube, The Nightmare may look over-staged and cheesy, but in the pre-MTV age it was made, when even film clips of rock stars were still rare, The Nightmare was a groundbreaking extravaganza. When it was later released on long-form video it was nominated for a Grammy, and won an Emmy for best editing. And, of course, it provided great publicity for the US tour, which sold out everywhere it went that year.

“The idea for the film was Shep Gordon’s,” Alice reveals now, referring to his manager. “I’d never done a TV special before, so we thought it would be great to make the whole idea visual, use TV as a rock’n’roll media.”

Vincent Price, he said, “was in his element, because he had me on a leash, walking me around, and I was just like being jerked around on this leash. I said, ‘Don’t be afraid to yank the leash. Make this like one of your movies where I’m just like this little pet of yours that you’re showing around’. So we had the best time. Vincent Price and I got along like he was my father.”

During breaks from the road, Alice was also now a keen golfer, hiring a Hollywood pro to teach him. When he wasn’t on the golf course, he was hanging out with Hollywood’s finest, such as Groucho Marx. Alice says: “I had the honour of being presented to him as one of his birthday gifts on his 84th birthday. We were introduced in the outdoor garden of the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel.”

Another unexpected celebrity fan was Peter Sellers. Alice recalls: “Peter insisted he wanted to change places with me on part of my tour. I had been on the road for seven months. At that point I would have switched with Sellers for a show, but only if I could play Inspector Clouseau in a movie.”

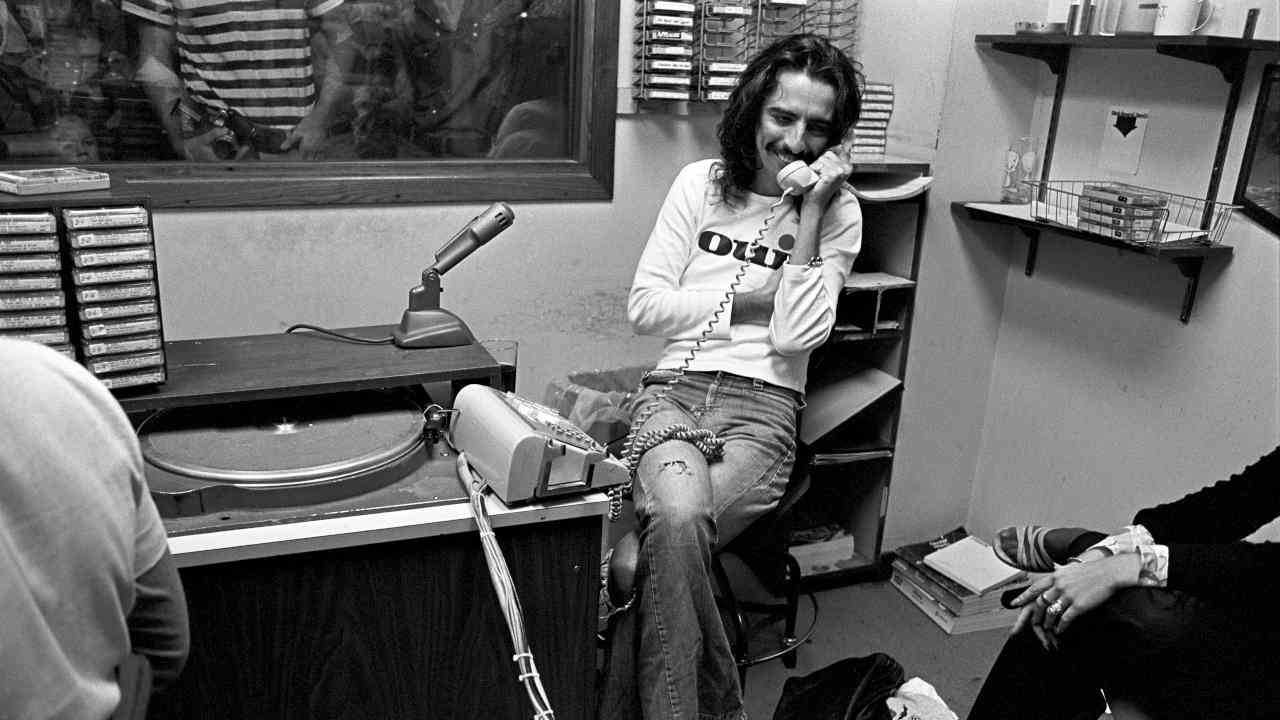

Alice would appear for TV interviews carrying a pitching wedge in one hand and a six-pack of Budweiser in the other.

“I drink and watch quiz shows,” he would say when quizzed about what he did all day in his hotel suite. “We got into theatre because this generation was educated in theatre by the TV. I mean, TV is my best friend. I like white noise when I sleep. If someone turns it off, I wake up.”

Sometimes, what he called “the old Alice” would appear. In Vancouver, at the Pacific Coliseum, he was so drunk he stumbled and fell from the stage, headfirst onto the concrete floor. Assuming it was part of the show, crazed fans reached for his blood-spattered head before bouncers pulled them off. He was taken to hospital, where doctors stitched his wounds and fitted him with a medical skullcap – but Alice insisted on being taken back to finish the show. He returned to the stage, nearly passed out, and was led off again.

Special guest on that section of the tour was Suzi Quatro. She recalls that Alice’s antics made “everybody quite frightened about the future of the tour. There was another time in Colorado, where he had to take oxygen and salt because it’s a mile-high city. Another time, we were bored and decided to have a dart-gun fight. And I’m a seriously good shot [and] got him right between the eyes. That night on stage he wore my T-shirt out of respect.”

Mostly, it was one long high. Travelling to the next gig on their private plane each day, tour manager Dave Libert would read out “ball scores” over the PA.

Alice recalled how cheers would greet such announcements as, “We have a pervert of the year award to give away today. This goes to Easy Arnie. Easy Arnie managed to get a BJ from a 64-year-old chambermaid 10 minutes before he checked out of his hotel room. Take a bow, Arnie! What an animal, folks!”

Then: “Last night there were four three-ways, three five-ways, six one-on-ones, and two one-ways with poor response. Once again, Jerry dated and fell in love with his own right hand last night...”

When the tour reached the UK in September, two shows at The Empire Pool – now the Wembley Arena – were shot for a concert film (there was a third, unfilmed, date at the Liverpool Empire). Released at the cinema the following year, it was destined to become a midnight movie classic in the US.

Before this could happen, though, Alice had to get into the country – something made unnecessarily difficult by MP Leo Abse, who had sought to ban him claiming that he was “peddling the culture of the concentration camp.” That had been in 1973. Two years later, said Alice, “I showed my passport at the customs at Heathrow and the next thing I knew I was taken aside and kept for an hour while inquiries were being made.” The tension was relieved by the appearance of one of the dancers dressed in the cyclops costume. “The people in immigration loved it,” Alice recalled. “The cyclops used a backstage pass as his passport and customs agents called him Mr Clops and welcomed him to the country in the name of the Queen.”

Speaking of which, Alice was photographed on this trip with Queen Elizabeth lookalike Jeanette Charles. He was also a hilarious guest on the Russell Harty TV show. “It was the best TV show I ever did. Harty and I loved each other from the start. I asked Harty to marry me and he looked shocked. ‘Oh, I heard about you on weekends’, I told him.”

It was not such fun in Australia, though, where Labour and Immigration Minister Clyde Cameron insisted he was “not going to allow a degenerate who could powerfully influence the young and weak-minded to enter this country and stage this sort of exhibition here.” Alice’s response: “I have never done anything nearly as bloody as King Lear or Macbeth, and that’s considered required reading in every high school in America.”

Despite these occasional outbreaks of PR-seeking outrage from politicos, Alice Cooper was already well on his way to national treasure status. No longer the bogeyman, with Welcome To My Nightmare Alice had reached a tipping point. His web cast wider than had ever seemed possible, it was no longer our womenfolk Alice Cooper was after. He was ready to ensnare us all.