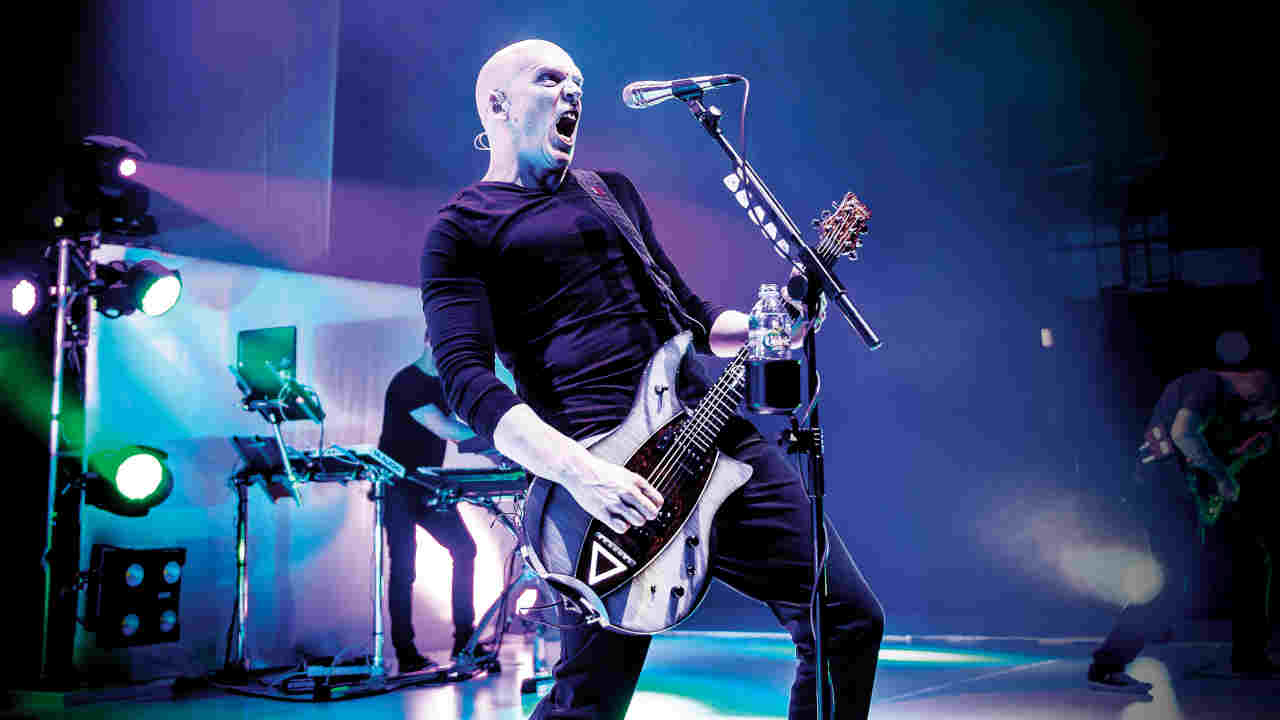

“I was always hoping that I would be taken away by aliens at some point”: The strange story of Devin Townsend’s Ocean Machine: Biomech, the album which launched his solo career

How Devin Townsend made his 1997 solo debut album Ocean Machine

Released in 1997, Devin Townsend‘s first proper solo album, Ocean Machine: Biomech, saw the then-Strapping Young Lad frontman spreading his sonic wings. In 2017, on the album’s 20th anniversary, he looked back on an album that would pave the way for his musical future.

When Devin Townsend was a child, his parents frequently took him on trips to the beach. They would tell him about a mysterious force operating in the sea: the seventh wave.

“I don’t know if it’s an old wives’ tale, but there’s a practical reality to it as well – it gains momentum,” he explains. “There’s the first wave, the second wave, and the seventh wave is typically known as one that is surprisingly big, and it sneaks up on you. You might be in the water and you don’t recognise it, and then you get hit by it.”

Seventh Wave is the name of the pulsating opening track on Devin Townsend’s first solo record, Ocean Machine: Biomech. Released in 1997, it explores the unexpected moments that unfold as a person comes of age. Intense and driven, it lacked the immediate bludgeoning impact of his then-band Strapping Young Lad, but was soaked in the emotional heaviness of his formative years, covering everything from his time on the road with the likes of Steve Vai and The Wildhearts to a shock high school experience of confronting mortality. It would become the blueprint for his future work, as he poured his raw experiences into songs that explored the universal theme of what it means to be human.

“I’m fortunate,” he admits now. “Very young I recognised that my proclivity for writing music allowed me to channel my feelings into something really tangible.”

He started writing the songs when he was just 17, and signed to Relativity Records to release them as a collection called Noisescapes, but it never came out. The label gave him back the tapes, and while he toured the world backing high-profile musicians, he tried to get it signed as Ocean Machine. With songs that ranged erratically from brutal to quiet, nobody would touch it. But Century Media was interested in the heavier material, and Strapping was born, putting out the none-more-metal Heavy As A Really Heavy Thing.

Yet Ocean Machine still lingered in Devin’s mind. So when a friend suggested he should set up his own record company, and offered to licence the album through Sony Japan, he jumped at the chance. He created HevyDevy Records, and then appealed to Daniel Bergstrand, who had previously worked with Meshuggah and by then was producing Strapping’s crushing second album, City.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I said, ‘Look, I’m doing this other thing that’s not signed but is really important to me, and if you would help me finish the mix on this, it would be of huge leverage for me to have it sound right,’” Devin remembers. “So he agreed, and did it for basically nothing. After recording Ocean Machine slowly over years in Vancouver and with shitty quality, I took it to Spain, and we had the hardest mix I’ve ever been involved with…”

The pair arrived in the coastal hotspot of Malaga in September 1996, as holiday season was winding down. Devin had booked two weeks at a studio on the seafront that he now refers to only as ‘Shithole’, and they set to work. By this time, some of Ocean Machine’s songs were already seven years old, and Devin was desperate to get them out of his system. Unfortunately, fate had other ideas. The studio owner would kick them out every afternoon, so he could get drunk with actor Antonio Banderas and his buddies.

“Antonio Banderas plays guitar, and it was a small town that they lived in, so he would go in at night with his buddies and they’d drink brandy and bash on these acoustic guitars until six in the morning,” Devin sighs. “As much of a cool story as that is, for a 24-year-old kid that was going crazy trying to get this impossible project done, with no money, I was just like, ‘Fuck off’, you know what I mean? Just give me my studio, I’ve got to finish this stupid record! Daniel and I went crazy trying to get this thing done.”

To make matters worse, the weather took a dramatic turn in the second week, bringing “biblical storms” and power outages. The studio was a back room in an equipment supply warehouse, and Devin and Daniel had run the kick drum through a PA system and into the cavernous space, before mic’ing it up to get a natural sort of reverb. But by the time they got to recording the snare, torrential rain was hammering the building’s tin roof, making it impossible to get a decent sound. Their solution? Sampling the first snare hit from Metallica’s Sad But True.

“If you listen to Ocean Machine, every snare hit has got that guitar behind it going, ‘Chunk’,” he smiles. “I kind of wanted it to sound like a Metallica record at the time, but we couldn’t make it work, so we just pressed play on the CD.”

Eventually, Ocean Machine’s 13 tracks were finished, with Devin making full use of every available inch of tape – he added the lung-splitting scream at the end just to push it to the 74-minute mark. Unfortunately, relations with the studio manager had soured beyond repair. They argued about the cost of hire, and he threatened to withhold the album, forcing Devin to take matters into his own hands.

“I actually had to steal it!” he confesses. “He was like, ‘Well that’s it, you can’t have your tapes unless you pay me this. And I was like, ‘Go fuck yourself.’ So I went in at night with Daniel, and we made a dupe of the master. I never saw the guy again…”

Layered and dense, affecting and reflective, the resulting songs encapsulate Devin’s early life. Some were about his career; the earnest, pacey Night focuses on his success in Japan. “I had spent a significant amount of time there, and I really romanticised it to an unhealthy level,” he admits. “You go to Japan and you’re treated like your shit doesn’t stink, when it very clearly does. But at the time I was infatuated by that. ‘Oh, they really like me there. They really like me.’ I was romantically remembering my experiences.”

Meanwhile, The Death Of Music refers to his time on the road with Steve Vai and the Wildhearts. “Because of my loss of idealism, the sort of deflowering at a young age, I think all of a sudden I realised, ‘Oh, it’s all bullshit. It’s all bullshit.’ Fame has got nothing to do with what is so important to me about expression.”

He admits to being more uncertain of himself at this age, publicly thrust into touring life, with a strong desire to be noticed by others.

“I mean, I annoy myself now, but back then I was such a weird dude,” he says. “I was so desperate for attention, and so full of anxiety. I think the core of who I am was there – I don’t think that’s changed significantly – but oh my god, man, I had an exhausting energy that I think affected the people around me quite negatively.”

Perhaps this is why he often expressed a yearning to escape the planet; in Hide Nowhere, Voices In The Fan and Greetings, he wishes to be abducted and spirited into space.

“I think I was always hoping that I would be taken away by aliens at some point,” he confesses. “I remember thinking it would be great if I could just not have to participate in this sort of cruel plane of existence – if I’m the special one that the aliens take away.”

But the most stirring songs on Ocean Machine are those that confront that cruel plane of existence head on. Life, a sonically uplifting rumination on the preciousness of existence, and Funeral, a hymn-like address punctuated with desperate cries, were written following the death of 16-year-old Jesse Cadman. On the evening of October 18, 1992, he was senselessly stabbed.

“He was killed walking home by a group of kids that wanted his hat,” says Devin quietly.

Though Devin and Jesse weren’t close, Devin was good friends with Jesse’s sister. He also played in local band Grey Skies, of which Jesse was a fan. When it came to organising his funeral, the Cadmans asked Devin to speak in church – something that left an indelible impact on him.

“I hadn’t experienced death in a tangible way prior to that, so when we went to the funeral and I had to speak, I remember I hadn’t anticipated they were gonna bring the body out, and I just panicked,” he says. “I couldn’t cope with it, and I wasn’t alone in that, either. It was a real heavy time for a lot of people, because it was our first experience with that sort of thing, and it was senseless. It affected my teen years profoundly.”

Jesse’s parents became involved in youth work and politics, and Devin is moved to learn that his mum, Dona Cadman, has publicly spoken alongside the mother of her son’s killer. “It’s a testament to the parts of the human condition that are worth fighting for,” he says.

Ocean Machine: Biomech was released on July 21, 1997, and the reaction was better than Devin had anticipated – he recalls that Metal Hammer awarded it 10/10. But beyond that, he had finally found a method for transmitting his innermost thoughts and shaping them into universal truths.

“When it comes to Jesse and Ocean Machine and Funeral, and all the things that happened, I think more than anything else, it established a mechanism for not only coping with emotions, but a process which to this day I employ with writing and performing music,” he explains. “Your life becomes the raw material for your output. One can argue that’s art in general, but had I not had the opportunity to really reflect on those things, it may have come out differently. I might have been writing rock songs about nothing.”

The record closes with Thing Beyond Things, all echoing vocals and dark imagery, moving towards the conclusion that when you examine life’s triumphs and trials hard enough, they become almost abstract components of a vast existence.

“It summarises the record by saying through all this, through all of the ups and downs, and the crests and ebbs and flows of this ocean even, it doesn’t really matter,” says Devin. “It’s all just things.”

This feature was originally published online in 2017

Eleanor was promoted to the role of Editor at Metal Hammer magazine after over seven years with the company, having previously served as Deputy Editor and Features Editor. Prior to joining Metal Hammer, El spent three years as Production Editor at Kerrang! and four years as Production Editor and Deputy Editor at Bizarre. She has also written for the likes of Classic Rock, Prog, Rock Sound and Visit London amongst others, and was a regular presenter on the Metal Hammer Podcast.