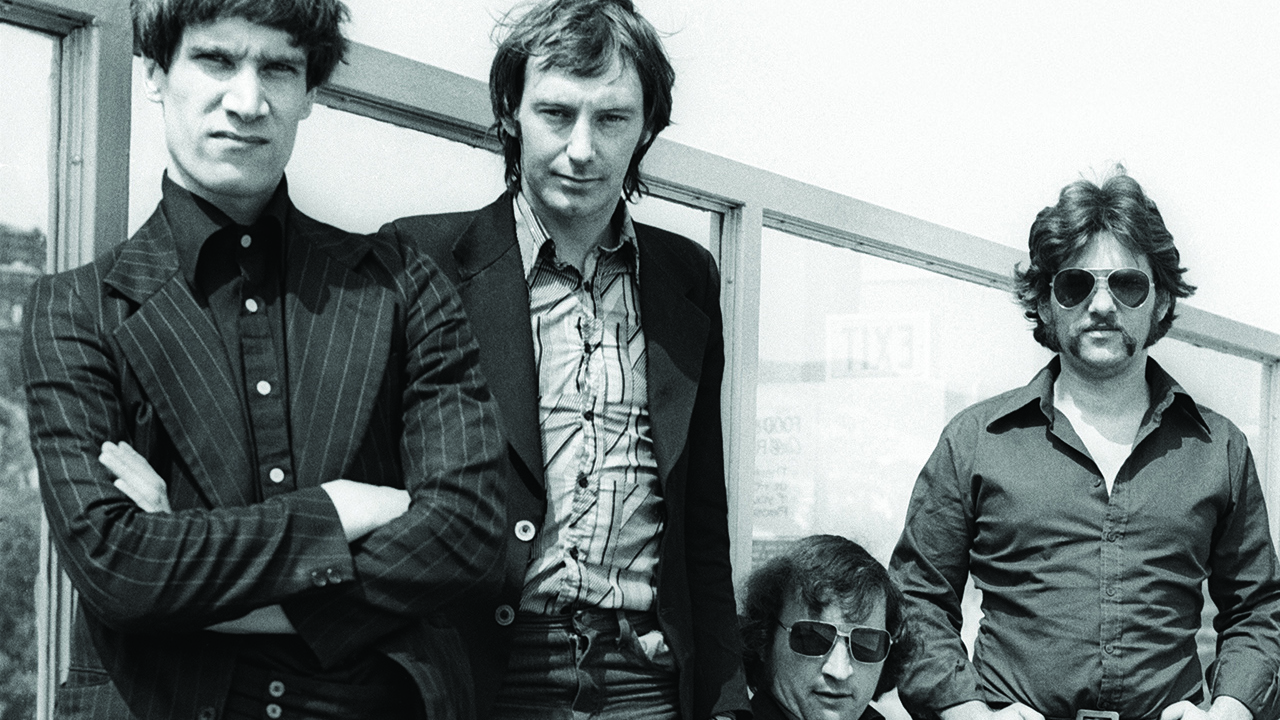

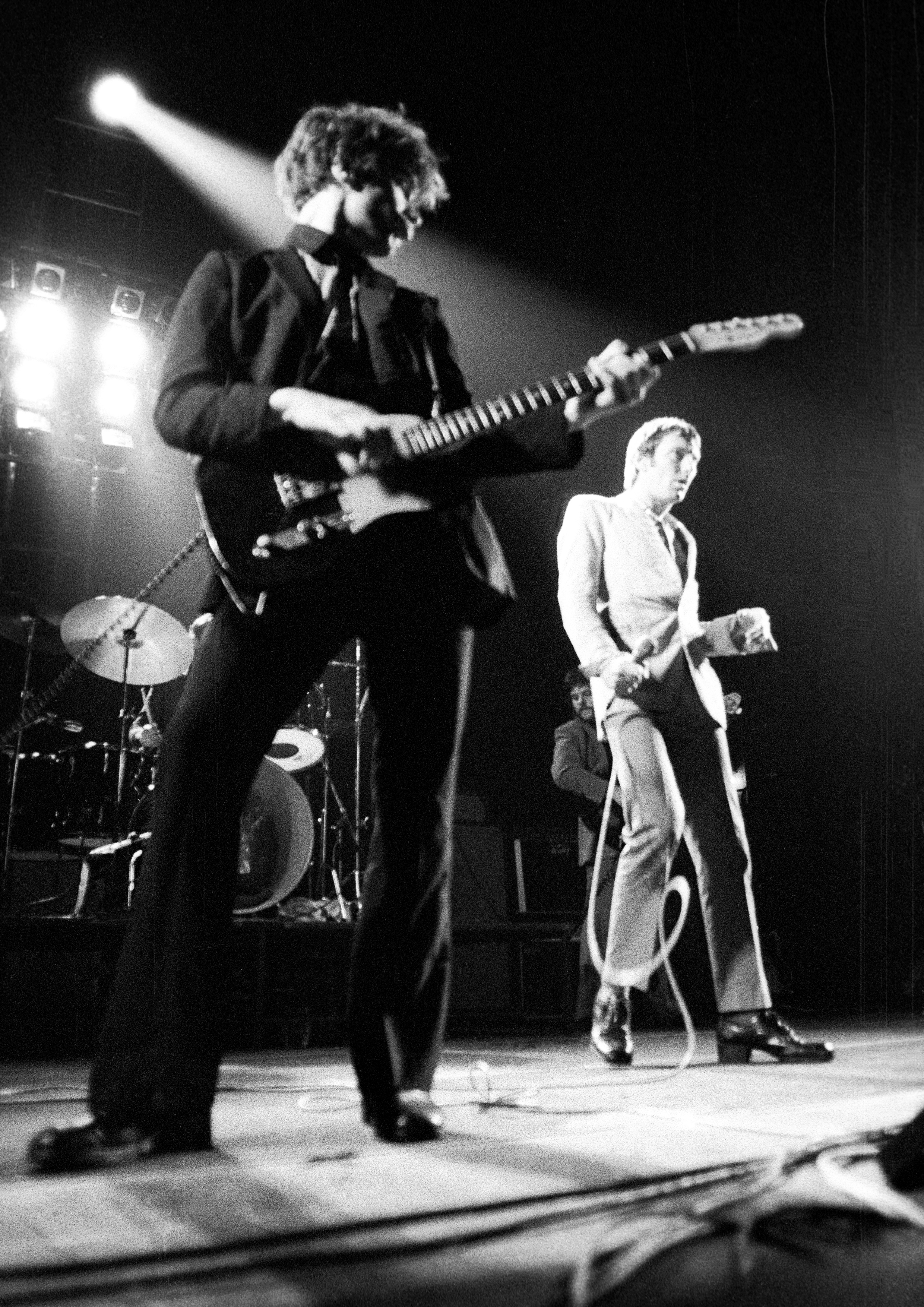

As 1977 dawned, Canvey Island pub rock supremos Dr Feelgood were enjoying their highest profile to date. With a media-savvy horde of punk iconoclasts gurning from the red-top tabloids on an almost daily basis, many in the rock establishment were casting nervous sideways glances, but the Feelgoods were untouchable. Embraced by the barbarians at the gate for their short, sharp R&B shocks, the brutal aggression of their demeanour and the unmistakable fuck-you shortness of their hair, the Feelgoods were widely thought to be significantly more synonymous with the solution than with the problem.

Their frill-free, electrifyingly live album Stupidity had topped the UK album chart in October (without the benefit of a supporting hit single, incidentally), and with New York abuzz America seemed ripe for the picking. Nothing, it seemed, could halt their rapid ascent.

With gale-force gusts of wind at his back, Dr Feelgood’s guitarist, sometime vocalist and sole songwriter Wilko Johnson set about writing an album with which to go global.

“I’m walking down this road in the rain on Canvey Island,” Wilko remembers, “and I’ve got this repetitive riff in my head, going over and over. When I get to a guitar and start playing it, a four-line chorus comes with the lyrics: ‘Every night you look so mean, staring at your TV screen’, and it ends with the words ‘Irene, Irene’. So I thought, oh blimey…

“Irene, she’s my wife. We were together since we were teenagers. We met down the youth club and I love her. We were together for forty years, until she died of cancer in 2004. Anyway, as I set about writing Paradise I thought, it’s going to be our story, and I’m going to sing it, not [Lee Brilleaux, Feelgood’s frontman].

“So I wrote how we were teenagers together on Canvey Island, hearing the skylark as we walked along the sea wall,

all that. There’s a bit about me wandering far from home, which went back to five years before when I went travelling to Kathmandu for six months and she couldn’t come with me. This is the only time I ever used a proper name in a song. When I’d needed a woman’s name before, I’d made one up, like Roxette.”

“When I was writing the song I realised it was going to be quite autobiographical, but I only wanted people that knew me and Irene to pick up on it so I left it a bit cryptic.”

As one might expect, some lines in the song are more cryptic than others. In fact the number of listeners fully able to decipher the line ‘I love two girls, I ain’t ashamed’ could probably have been counted on the fingers of one hand.

- Wilko Johnson - Don’t You Leave Me Here: My Life book review

- Lee Brilleaux: The Forgotten Man of Dr Feelgood

- Wilko Johnson Q&A: "Lemmy sussed me out as a speed freak"

- Wilko Johnson And The Best Of Chess Records

“Well, yeah… you know,” Wilko begins unpromisingly, before admitting: “When I had the money I used to keep a girlfriend. Her name was Maria McCormack. Her and Irene knew each other. And that verse was me saying to her: ‘Listen, you give me a thrill and that, it’s great, but Irene’s my old lady.”

Meanwhile, Paradise’s peculiarly personal lyrics were not going down too well with Wilko’s bandmates in Dr Feelgood.

“We’d rehearsed Paradise at Feelgood House before we went into Rockfield Studios to record.” says Wilko. “We had a really shabby PA and you couldn’t really hear the lyrics. But when we went into the studio they all heard the words and there was an argument. And one of the things they were chucking about was: ‘That fucking song, it’s a fucking ego-trip.’ And I’m going: ‘It’s not, you c**ts, it’s a good song. You’re only going on because you know who it’s about.’ Stuff like that was going back and forth – ‘I don’t like this’ and ‘I don’t like that’ – and by the morning I was out of the band.”

“If Irene’s name hadn’t been in it, they would never have known. Anyway, they were wrong about it, because I’ve always played this song and it’s always been very popular. I dunno,” Wilko says, frowning, before concluding: “I think they just wanted a stick to beat the dog with.”

Wilko’s old mate Lemmy probably presented the best theory as to why the Feelgoods split along the line that they did: “This is what happens when three-quarters of the band are drinkers and one’s a speed freak,” Lemmy offered. Ultimately it’s pretty fair to say that the demise of Dr Feelgood Mk1 had significantly more to do with a (recreational) chemical imbalance than with the autobiographical nature of Paradise’s lyrics.

“So there was that,” Wilko says, sidestepping the question, characteristically reluctant to linger unduly on the painful minutiae of the Feelgoods’ split.

“And then in 2004 when Irene died I couldn’t play that song any more, so I stopped playing it. But people still wanted to hear it; they’d call out for ‘Irene’, as they called it. So I rewrote that third verse to incorporate her death, and we started playing it again. The way I do it now, it’s got this line: ‘Now you’re sleeping in your grave’, and I do get a little bit choked singing that one, you know. I lose the rhythm, lose the riff, and I have to think to myself: ‘Oh, don’t do that.’ It’s stupid.”

So which was the best decision of Wilko’s life: to join Dr Feelgood, or to marry Irene?

“There’s absolutely no question of that at all,” he answers, laughing. “All you really needed to have asked was: ‘What was the best decision of your life?’ It’s so completely obvious that it was to marry Irene. Sometimes you have to stop and ask yourself: ‘How lucky was I?’ And I was very lucky there.”

Probably not a day goes by without you thinking about her?

“A minute doesn’t go by.”

A lotta bottle…

“We did two tours of America and during that time the friction between me and Lee got acute,” Wilko Johnson begins, talking about the background to the Dr Feelgood split. “We couldn’t really be in the same room together.

“During those tours the rest of the band really started hitting the bottle. They’d be drinking first thing in the morning, whereas I was teetotal. I wouldn’t be down in the bar when everybody was getting pissed, I’d be up in my room. And this was the situation that drove us apart. I was a bit of an arsehole, actually. I was hard to get on with sometimes,

bit of a ballerina.”