It was 2004, and, for perhaps the first time in his life, Ken Casey of Dropkick Murphys was at a loss for words. As far back as anyone in Boston could remember, the band’s co-founder, co-frontman, bassist and de facto leader had been the city’s best-known mover, shaker and hustler.

“I always just felt like I knew everyone in this town,” Casey remembers. “Even before I was in a band, I’d be booking all-ages punk shows at The Rat, which was like our CBGBs. The Boston punk scene was just exploding.”

When they formed in 1996, Dropkick Murphys were protagonists of that same downtown crucible of punk, their rabblerousing punch granting them entry to the scene despite a sound steeped in Celtic folk. Eight years later their blue-collar work ethic had helped them chalk up four albums and a thousand sweat-drenched shows.

“We’d rehearse at seven a.m.,” recalls Casey, “and the borderline-homeless guy who took care of the rehearsal studios would scratch his head and tell us that most people get into music so they didn’t have to work those hours. But it made us feel like we had a real job.”

All Dropkick Murphys were lacking was a hit. But now, as the line-up rumbled through a promising new instrumental that fused malevolent stabs of bass with a light-footed accordion and banjo hook, Casey knew they were within touching distance – if only they could put pen to paper.

“James [Lynch, guitarist] had come up with the riff and it was so powerful,” Casey recalls. “But I was just labouring to find a lyric that worked with it.”

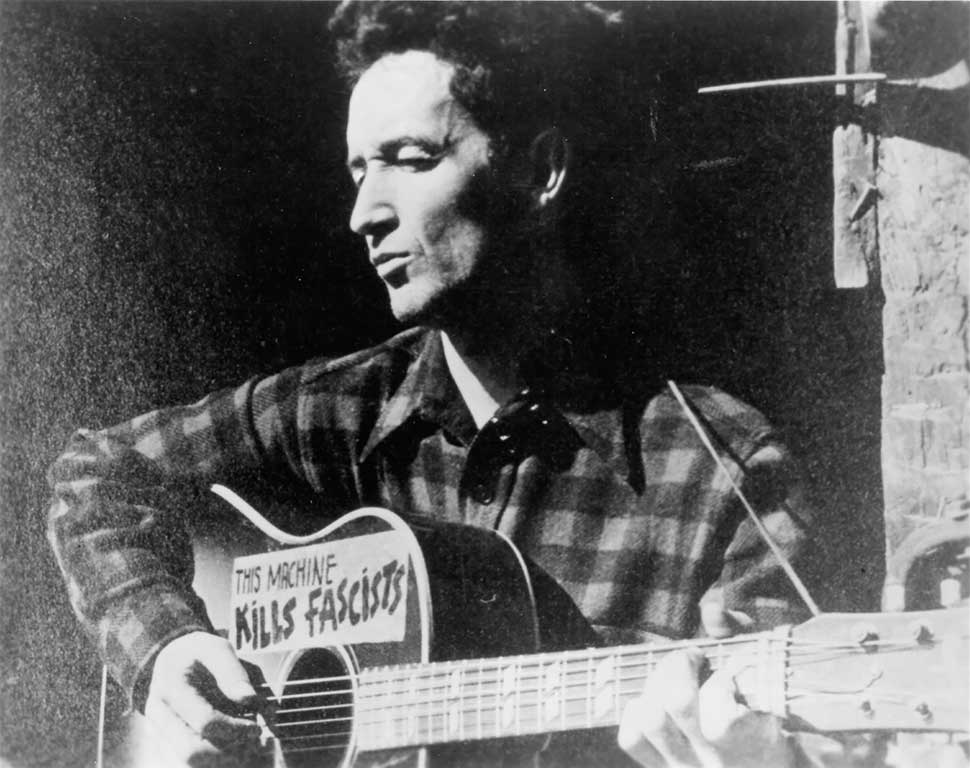

The answer came from beyond the grave. By the turn of the millennium, trailblazing American folk singer Woody Guthrie had been dead for more than 30 years. Yet the socio-political power of his work still burned hot, from his endlessly relevant signature tune This Land Is Your Land, to the ‘Arm The Homeless’ graffiti scrawled by Rage Against The Machine’s Tom Morello on to his guitar (a nod to Guthrie’s acoustic, which proclaimed: ‘This Machine Kills Fascists’).

Never shy of a polemic themselves, Dropkick Murphys were heavier than Guthrie but firmly in his lineage.

“The guy spoke up,” says Casey. “He was ahead of his time. I mean, he even wrote a song, Old Man Trump, about Donald Trump’s father being a slum lord. Around the time we were writing that instrumental, we got an invite from Woody Guthrie’s daughter, Nora, who runs the Guthrie Archives. She told us: ‘If my father had been born in your era he would have been playing music like you.’ Which was such a huge honour.”

Nora Guthrie hadn’t called just to pay the band a compliment. “She told us her father had thousands of songs that were never put to music, just pieces of paper torn from notebooks. I said: ‘My God, I’d love to come down to the archives.’ I had to put on special white gloves, and I held these pieces of paper in the palms of my hands like I was holding a newborn child.

“So I’m going through these lyrics, which are deep, political, rebellious, heartfelt. All of a sudden I stumble on I’m Shipping Up To Boston, which is only five lines long. I was just, like: ‘What the fuck is this?’ It was so out of left field. But within seconds I said: ‘My God – that’s the lyric.’ The words fell right into our instrumental. And the Guthrie estate were ecstatic, because it was giving life to a song that would otherwise have just sat in a folder somewhere.”

Written from the perspective of a peg-legged sailor whose limb had been wrenched off in some terrible nautical mishap – with the title repeated four times by way of a chorus – those scant lines of text posed more questions than they answered.

“Was he down on the waterfront, looking at the ships?” Casey wonders. “He probably wasn’t actually seeing a peg-legged guy – it’s not like we had pirates in Boston Harbour in 1950. I really don’t know. But the ambiguity makes it a better song. To me, the words felt light-hearted. And we’ve always had a few songs on every record that don’t take themselves that seriously. I like to think I’m someone who laughs sometimes, not just the guy who walks around bitching about Donald Trump twenty-four-seven."

Perhaps the lyric didn’t catch Guthrie at his most poetic or politically engaged. But the simplicity and repetition, Casey argues, made I’m Shipping Up To Boston even more powerful: there was officially no easier anthem for a St. Patrick’s day crowd to bellow, even after drinking a river of Guinness.

“You think about AC/DC, who are one of our favourite bands. If there was a shit-load of noodling and drum fills, it’d lose all its power. And that’s where I’m Shipping Up To Boston got its power too. It was the first time in our career that we ever just left space.”

For its first run-out, in 2004, I’m Shipping Up To Boston had a low-key release on the fourth edition of the Hellcat label’s cult Give ’Em The Boot compilation (“That compilation was responsible for breaking us in a lot of ways,” says Casey, “so we felt like we couldn’t say no”). But the version that bottled the anarchy – and caught the ear of film director Martin Scorsese, who used it on the soundtrack to his Oscarwinning film The Departed – was the one on the Murphys’ 2005 album The Warrior’s Code.

“After that we decided to make a music video with our own bootleg version of The Departed,” explains Casey. “The ‘police’ and ‘hooligans’ were real. They’re all friends of ours.”

Five lines might not be much. But, 17 years later, for Casey there’s still nothing like performing I’m Shipping Up To Boston.

“People ask me if I get sick of that song. No, I never have. The beauty of I’m Shipping Up To Boston is that it’s only two minutes long. It leaves you wanting more."

Dropkick Murphys' Turn Up That Dial is out now via Pias.