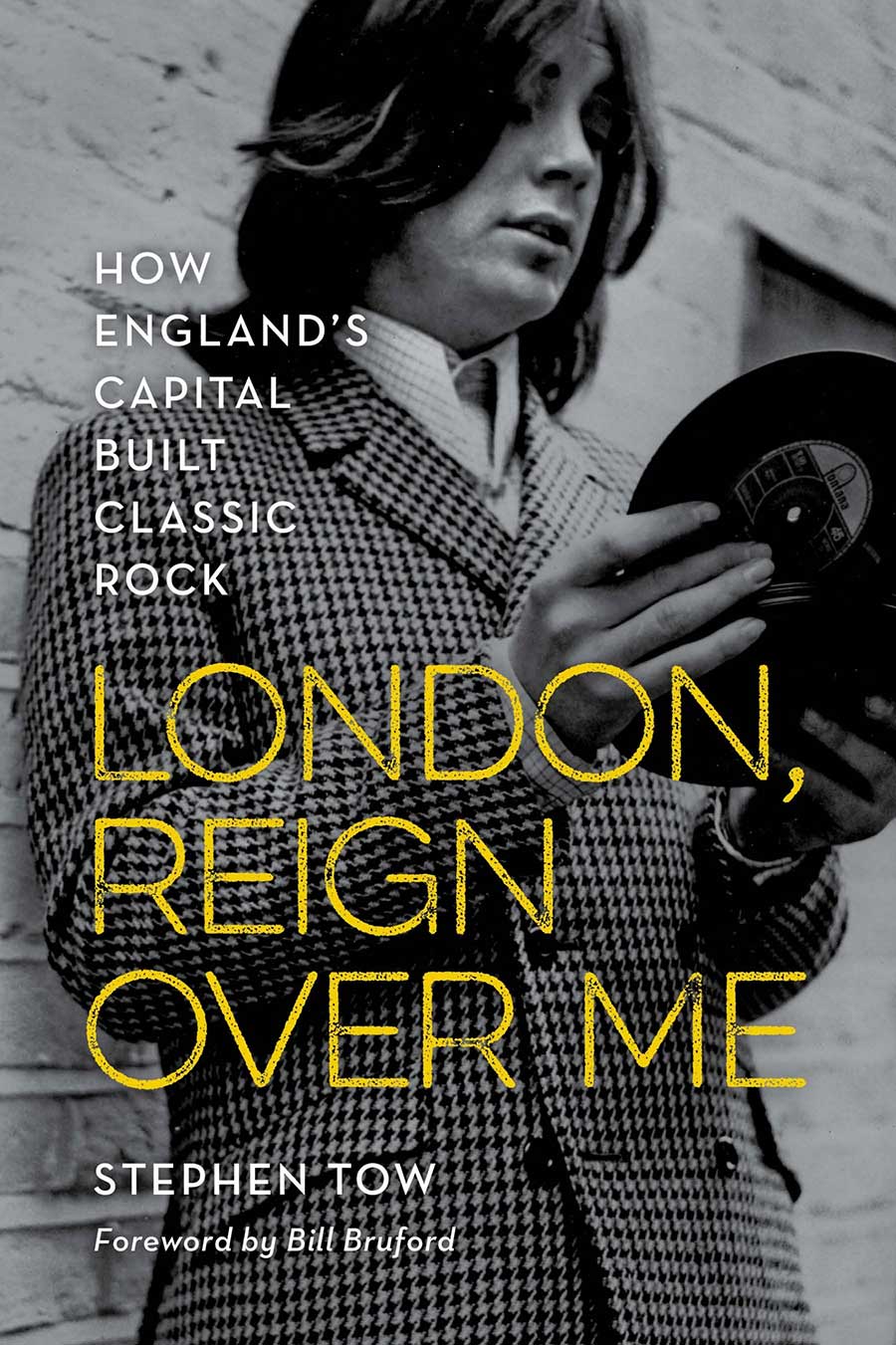

Stephen Tow's 2020 book London: Reign Over Me - How England’s Capital Built Classic Rock tells the story of London's impact on rock music, from skiffle and late night raves on Eel Pie Island to the blues boom and the birth of progressive rock.

With a forward by Bill Bruford and featuring interviews with Ian Anderson, Jon Anderson, Dave Davies, Peter Frampton, Roger Glover, Greg Lake, John Mayall, Carl Palmer, Richard Thompson, Rick Wakeman and dozens more, it transports the reader from the wreckage of post-war London on a journey to uncover the story of classic rock's birth.

In the excerpt below, Roger Glover explains the story behind Smoke On The Water.

Stephen Tow's London: Reign Over Me - How England’s Capital Built Classic Rock is out now.

Ritchie Blackmore came up with the classic riff.

“I thought [I’d] play [Beethoven’s fifth symphony] backwards, put something to it,” he stated in a 2007 interview. “That’s how I came up with it. It’s an interpretation of inversion. You turn it back, and play it back and forth, it’s actually Beethoven’s fifth. So I owe him a lot of money.”

That may have been a joke given Blackmore’s sense of humour, but one thing isn’t. He wrote the riff in 'fourths,' which is a medieval style of writing. He had played around with that type of writing for a few years before stumbling upon what would become the iconic riff of Smoke On The Water.

The story about the song’s creation somewhat mirrors that of Free's All Right Now and other classics written as toss-offs and in a hurry.

Deep Purple were in the midst of recording their seminal 1972 album, Machine Head, at a casino in Montreux, Switzerland, when somebody set off a flare gun and the building burned to the ground. This was during a performance by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. So Deep Purple had nowhere to record.

“The guy who was in charge of the casino and kind of looking after us, came to us,” Glover recalled, “and he put all his problems aside and was worried about us. Our equipment was there. We were there. We had no place to record. So he arranged to have us move into a small theatre nearby the old casino – the ex-casino, I should say.”

The band set up on the stage and ran cables out to the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio. Recording began in the afternoon. The band took a break for dinner and returned to the studio around 9 or 10 p.m.

“We started jamming a bit,” said Glover. “And Ritchie just started this riff. I don’t know if he had the riff beforehand or whether he made it up on the spot, but it was a kind of mid-tempo, ploddy kind of riff. It came together fairly quickly. ‘Well this is a verse, we need a chorus. How about this? How about that? Let’s do a solo.’ And by the time we started recording it, it was [about] midnight.

"We were doing the first take of this song – well, it wasn’t a song yet. It was just a jam with a kind of rough arrangement to it. And what we didn’t know is that the police were trying to get in and stop us because we were keeping the whole town awake. Montreux was then a very sleepy town populated mostly by old ladies who had tea in the afternoon.”

So now the band had to find yet another place to record in this small, idyllic, quiet town. There weren’t many options, and it took a few days to find a suitable space.

“So we came across the Grand Hotel,” Glover recalled, “which was then closed for the winter. A cold sort of place, I mean it was freezing cold, after all [it was] November, December time. We arranged to have a carpenter put a couple of walls up. We threw some mattresses against the windows, brought a couple of industrial heaters to heat the place before we arrived there during the day. And [we] basically recorded there.

"We did Highway Star and Lazy and Pictures Of Home and all those. And we finished all those and we were still short of a song. ‘Well what about that one jam we did at that other place?’ ‘Yeah, ok. Well, what are we going to do with it?’

"‘Let’s write a song about the adventure of actually coming to try and record, and the place burning down and ending up doing it in a hotel corridor. Let’s write an autobiographical song.’

"And Ian [Gillan] and I sat down and we listened to the song. We said, ‘Right, well let’s write some lyrics.’ And we wrote them quite as conversationally as I’m talking to you.

“I came up with the title a day or two after the fire,” Glover recalled. “I said it half asleep as I was waking up, I realised I just said something out loud in the hotel room – to no one. There was no one there. Just me. And I thought, ‘Did I just say something out loud? What was it?’ ‘Smoke on the water.’”

“We never thought for a minute it was going to have the kind of future it was gonna have,” adds Glover. “We didn’t think that much of it. We thought, ‘Mid-tempo, slightly boring.’ We put all our efforts into another song on the album called Never Before. We thought that was going to be the single. But it wasn’t us that chose Smoke On The Water.

"It was first of all some DJs, and then the public at large turned it into the song it’s become. Now, listening to it, it’s obvious. The riff is so simple and yet so different to anything else. And I know, Ritchie himself has said it’s like Beethoven in a way – Beethoven’s fifth.

"What Beethoven does with just very few notes, that riff does it with very few notes, too. But it’s got a hint of Eastern mysticism in it, just by the semitone lift. Instantly recognisable and yet nothing like anything else. In retrospect, Smoke On The Water is pretty hilarious. It’s like writing a song about any mundane daily activity: 'I went to the grocery store / To buy some cheeeese.'"

But in this case it turned into an all-time classic.

Stephen Tow's London, Reign Over Me: How England's Capital Built Classic Rock is available now.