By the late 60s, Morocco was fast becoming an essential stop-off point on the new hippie trail. It was a place frequented by seekers of all stripes, from travellers and the more adventurous tourists through to artists, writers, fashionistas and rock stars. They were all drawn by the exotica of this storied corner of North Africa, whose heady promise of spiritual enlightenment and hashish served to melt away the conventions of the West.

In 1966, Graham Nash made a pilgrimage of his own, one that sparked off one of his most famous songs. On holiday from his day job as leader of The Hollies, Nash bought himself a ticket and hopped aboard a train from Casablanca to Marrakesh. “I was in first class and there were a lot of older, rich American ladies in there, who all had their hair dyed blue,” Nash recalls today. “And I quickly grew bored of that and went back to the third class of the train. That was where it was all happening. There were lots of people cooking strange little meals on small wooden stoves and the place was full of chickens, pigs and goats. It was fabulous; the whole thing was fascinating.”

So rich was the experience that Nash poured it into a vivid piece of psychedelic pop: Marrakesh Express. Mellifluous, carefree and irresistibly catchy, the lyrics made reference to ‘animal carpet wall-to-wall’, ‘coloured cottons’ in the air and ‘charming cobras in the square’. But they also hinted at a vague sense of dissatisfaction with life, as if Nash was on some indefinable quest for something better. Particularly the lines: ‘Sweeping cobwebs from the edges of my mind/Had to get away to see what we could find.’

The song itself was written during The Hollies’ Yugoslavian tour of June 1967. It was one of a number of new tunes that showcased Nash’s outward growth as a songwriter as he attempted to steer The Hollies away from the confines of the singles market into the more lysergic, experimental realm of peers like The Beatles and The Byrds – though the rest of the band didn’t all share his vision. Initially reluctant to record Marrakesh Express at all, The Hollies only got as far as cutting a backing track at Abbey Road in April 1968. Nash, who remembers that “it wasn’t very good”, explains that he’d written a bunch of similar songs at that point – among them Lady Of The Island and Right Between The Eyes – which The Hollies weren’t moved by either.

It wasn’t just the tunes. Nash’s burgeoning interest in the counterculture and its lifestyle meant he was the only band member to embrace LSD and marijuana. Allied to the fact that King Midas In Reverse, one of his finest compositions, had only been a moderate hit, Nash sought a move away. “Yeah, it was obvious that my career with The Hollies was coming to an end,” he says.

Not that Nash hadn’t planned for the immediate future. On his first trip to LA with The Hollies, in June 1966, he’d been introduced to the Mamas & The Papas’ Cass Elliot, one of California’s leading scenesters. She in turn had introduced him to David Crosby, ace harmony singer and songwriter in The Byrds. “I’d been in a showbiz environment with The Hollies,” says Nash, “but Crosby and The Byrds weren’t like that. So there may have been a cultural difference, but there weren’t any musical differences with us. I knew he was serious as a heart attack about his music, that The Byrds were a great band and that the modal stuff I was attracted to in their music was mainly down to David. When Cass introduced us, it was instant friendship.”

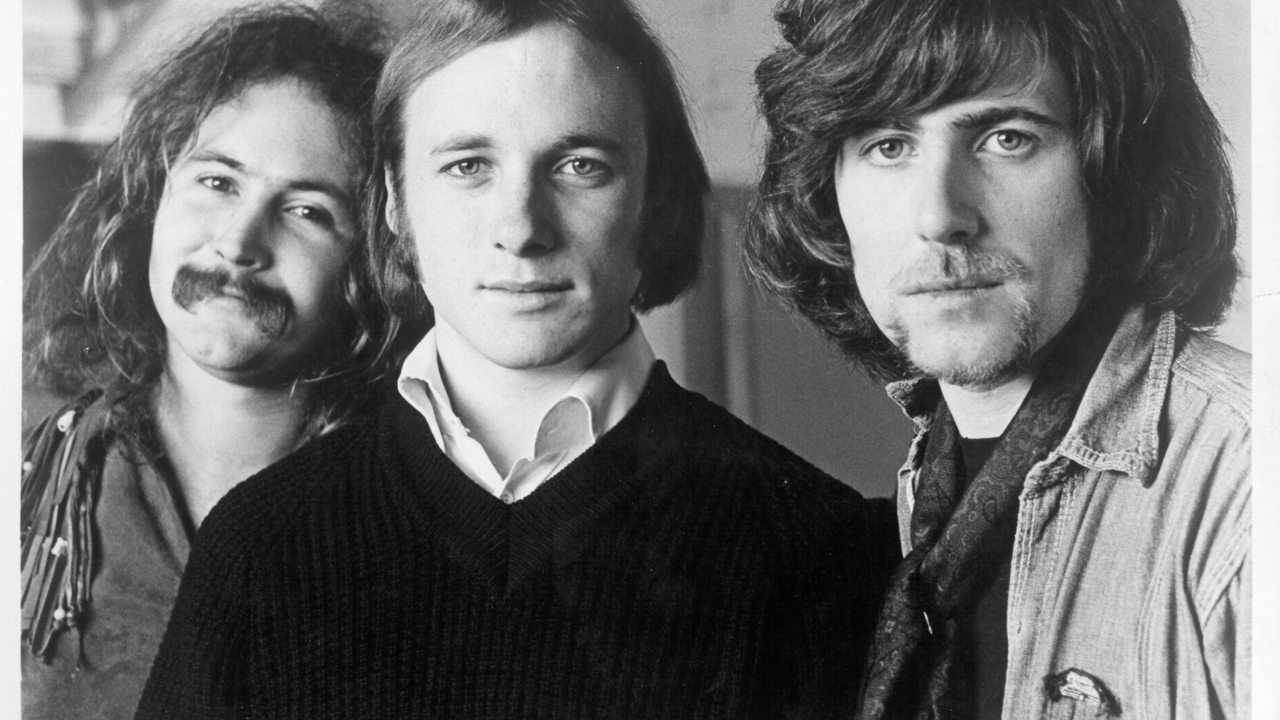

Crosby and Nash would bump into each other regularly over the next couple of years and, by the summer of 1968, both men found themselves at a critical juncture in their respective careers. Ever the egotist, Crosby had been ousted from The Byrds less than 12 months earlier. And while Nash had already decided to quit The Hollies, Stephen Stills’ tenure in dynamic LA rockers Buffalo Springfield had also come to a close. Stills and Crosby had been jamming informally for months before Nash was invited into the fold. The rapport was sensational. Grounded by Stills’ masterful guitar playing and achieving lift-off with their gorgeous three-way harmonies, Crosby, Stills & Nash were suddenly a serious concern.

- Q&A: Stephen Stills

- David Crosby on protests and politics, life and death

- Graham Nash: This Path Tonight

In November 1968, Nash officially left The Hollies, heading out to California and taking up temporary residence at Crosby’s place. When it came to selecting songs for their self-titled debut album, Nash revived Marrakesh Express. Easily the most ‘pop’ song in the CSN canon, it was recorded at Wally Heider’s LA studio in February ’69. Stills’ guitar races along at a clip, echoing the literal rush of Nash’s Casablanca train and imbuing the song with a wondrous sense of buoyant optimism. There’s a smattering of nonsensical wordplay to begin, before Nash begins to sing in his warmest tones, exhorting everyone to climb aboard. You can almost feel the sunset through the windows.

Issued in May 1969, the album marked out Crosby, Stills & Nash as America’s first great supergroup and provided the counterculture with its definitive soundtrack. Marrakesh Express was released as the lead-off single and made the Billboard Top 30. Over here it reached No.17 and remains the only UK Top 20 hit of CSN’s entire career. It’s a song that continues to run on in its creator’s heart.

“I thought it was a funny song when I wrote it,” says Nash. “It’s not the greatest song in the world, but people still really like it whenever we sing it live. Whenever we need a little light-hearted, uptempo thing, that’s what we reach for.”