Big Star wrote it, Jamie T sampled it, and it was one of Jeff Buckley’s favourite songs. The story of the sleazy song that was reimagined to capture “the beauty of despair”

40 years ago, a Cocteau Twin and a young noise-rock singer from Scotland played together on a song they’d only just heard. It became “one of the best singing performances ever”

“Ivo didn't let me hear the song before I went to the studio,” says Cinder Sharp, the singer of This Mortal Coil’s 1984 single, Kangaroo. “I walked into the studio, Ivo put it on, said, ‘This is the song I want you to sing,’ and I immediately went: ‘This is shit! This is a shit song!’"

“I mean, I've completely changed my mind,” she says. “I love the original version much more than my own. But I didn't get it. I didn't understand the kangaroo part.”

40 years ago, This Mortal Coil’s debut album It’ll End In Tears went to number one in the UK Independent Charts and the album’s lead single – that ‘shit song’ – Kangaroo, went to no.2 and stayed in the charts for 20 weeks. Over the years, Kangaroo has been over-shadowed by another song on the album – Elizabeth Fraser’s haunting cover of Tim Buckley’s Song To The Siren – but This Mortal Coil’s Kangaroo remains an astonishing take on a song that’s had multiple lives.

Comments under the official video for Kangaroo on YouTube show the sort of esteem in which it’s held:

“I genuinely don't think I would have made it to this point in my life had it not been for this project.”

“I can safely say that this gorgeous piece of music – so beautiful, so sad, so reverent – is among my ten favorite songs of all time.”

“This song made me cry at first hearing, hauntingly beautiful…”

“One of the best singing performances ever.”

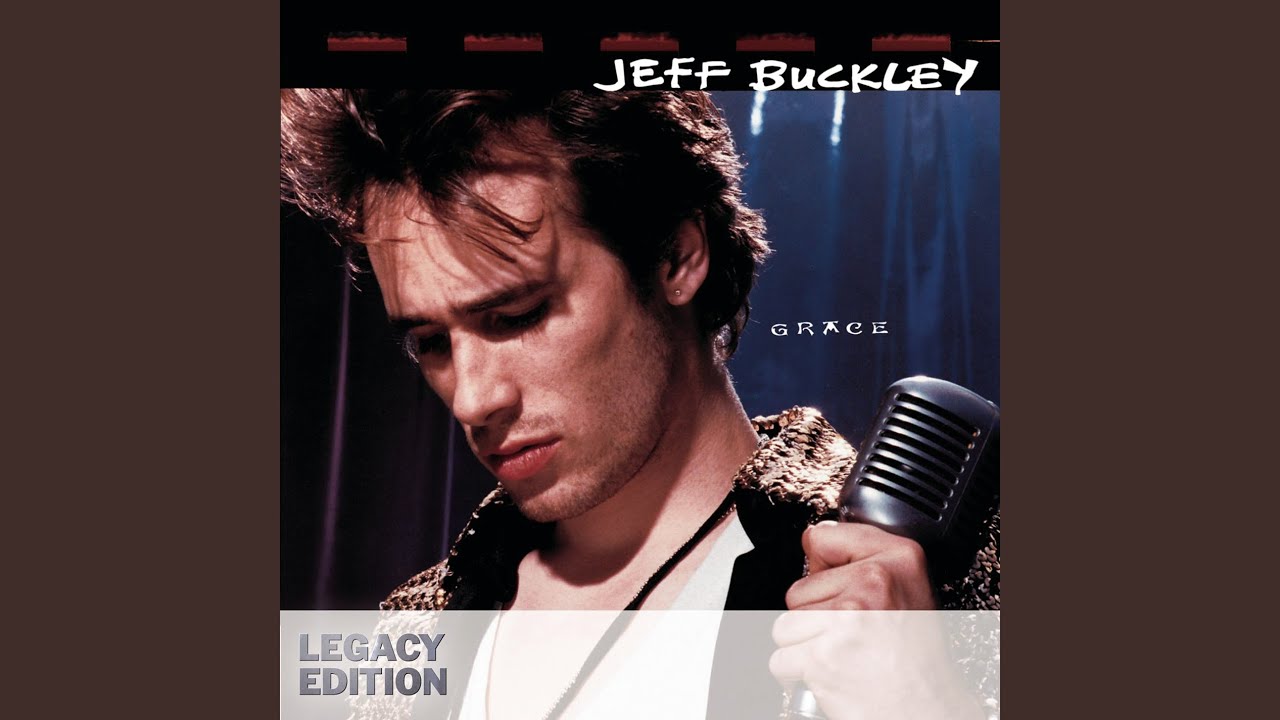

Initially written by Alex Chilton for what’s known as Third – the unfinished third album by Big Star – Kangaroo was resurrected by This Mortal Coil in 1984, covered by Jeff Buckley at live shows throughout the 90s, and was most recently sampled/interpolated by Jamie T on his 2022 single 90s Cars.

Cinder, known back then as Gordon Sharp, was the lead voice on It’ll End In Tears – the voice that opened the album, and closed it, and is on the song that gives the album its title. “Technically, the album had its title first,” says Cinder, “and I just stole it. Do you know what? It never occurred to me that Ivo might have been a bit pissed off with me for doing that!”

A loose collective of musicians from the 4AD label, led by Ivo Watts-Russell, the owner of 4AD, This Mortal Coil included members of the Cocteau Twins, Dead Can Dance, Colourbox, and like-minded collaborators like Howard Devoto (formerly of Magazine and the Buzzcocks) and Cinder, then as now, the frontperson for Cindytalk.

Cinder was from Linlithgo in the east of Scotland, between Grangemouth and Edinburgh, and knew the Cocteau Twins from the scene around the Grangemouth International Hotel. Robin Guthrie’s older brother Brian booked bands there, and Robin could often be found hanging around, Djing and checking out everyone’s guitar pedals. Elizabeth Fraser would always be at the gigs, says Cinder, whose band at that time was The Freeze. “She was this little skinhead punk girl who would be like a whirling dervish in front of the bands that were playing, including us.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Later, after she moved from Edinburgh to London, Cinder sang back-up with the Cocteau Twins. “I did a Peel session with them in early ‘83,” she says. “I’d only been in London a year and they came and stayed with me. We did quite a few gigs together as well. That was where Ivo saw me and invited me to participate in the Mortal Coil thing. He'd seen me on stage with the Cocteaus, doing just pure improvisation.”

Ivo was looking for singers for a project. 4AD had started life as an off-shoot of Beggar’s Banquet records. By 1984, it had developed a signature look, thanks to the designs of Vaughan Oliver, and its proudly post-punk and defiantly progressive music was reinventing art-rock for the 80s. Ivo had co-produced artists like the Cocteaus and worked with Xmal Deutschland but he wanted a project of his own.

“I wasn’t a producer,” he told the Melody Maker at the time. “I was just someone with ideas for sound. It was always their material, so why should I be interfering? This Mortal Coil became a method of being the person who had the final say.” A non-musician, he surrounded himself with artists and worked with fragments of songs. He was trying to capture, he said, “the beauty of despair”.

At best, the original version of Kangaroo (or Kanga Roo as it was called then) written and recorded by Alex Chilton captures exactly that – a drug-drenched fever-dream – at its worst, it’s the sound of a man having a late-night meltdown. “It’s like a cross between the Velvet Underground and Syd Barrett on heroin,” said Ivo. “Alex Chilton must have been in a very dark, despairing frame of mind and, shit, I’m moved by that in music.”

Colin Meloy of The Decemberists has done an in depth breakdown of the Chilton version. Referring to the track logs, he says the story goes that Chilton went into the studio very late at night, with his girlfriend Lesa Aldridge, and recorded the song with a 12-string guitar. (Big Star drummer Jody Stephens was dating Lesa's sister, which is where "Sisters Lovers" comes from – there is some confusion as to whether it was suggested as the name of the album or the band.) In the morning, Chilton played it to producer Jim Dickinson. Dickinson asked him what he wanted him to do and Chilton said, “Well, why don’t you produce it, Mr. Producer?” All the other instruments on the track are by Dickinson.

The cult of Third (also known as Sister Lovers, a mooted name for the band) has grown over the last few decades. As the entry on Alex Chilton in Britannica points out, “songs such as Kangaroo offered a glimpse of the noise-pop sound that would emerge in the 1980s with groups such as the Jesus and Mary Chain and My Bloody Valentine”. But in 1984, pre-internet, way before CD reissues, let alone streaming, Third was a pretty difficult album to find.

Cocteau Twins bassist Simon Raymonde hadn’t heard the song until the day he played it. “I arrived at the studio at 11am and my first ‘job’ was to listen to Kangaroo by Big Star’s Alex Chilton which Ivo wanted to cover,” Raymonde recalled in his book from this year, In One Ear. “He wanted a minimal take. The main instrument was to be bass. Ivo may well have given me a cassette of it a few days in advance I am not sure, but I know that I hadn’t had a chance to listen to it until I arrived.”

He played an Ibanez Musician eight-string bass and added “a kinda flute sound” using a Yamaha DX7. Martin McCarrick from Marc Almond’s band the Mambas (later of Siouxsie and the Banshees) added cello. And that was the only instrumentation – no guitars, no drums.

Next up: Cinder. Ivo gave her the lyrics on a piece of paper as she listened to the song for the very first time.“I didn’t get it back then,” she says. “I didn’t understand the ‘kangaroo’ part. So I had to think about it. I had to figure out a way to perform it, genuinely, with heart and soul.

“I doubt very much if I listened to it more than three times on the day that I sang it,” she says, “and probably only twice before actually performing it. What you're hearing on the record is pretty much my instant response.”

And what you hear is incredible. “In that moment, I changed the whole dynamic of the song,” she says. “God knows how I managed that. That’s just sink or swim, isn't it? You're thrown into a studio, you're given a sort of diagram of what you have to do, and you've got to just make it work.

Where the original is wasted and sleazy, Cinder’s Kangaroo is strong and defiant and pure. “I knew I couldn't do it like the original,” she says. “It sounds like it’s drug-induced, like it's very destructive. It's falling apart, falling over itself. And I didn't feel any of those things in that moment. I wasn't drunk. I wasn't on drugs. I wasn't sort of devastated in a relationship. So it was like, 'How the hell?'

“So I've always wondered if there was something else I was communicating,” she says. “Some other emotions, some deeper things that came directly from me, that were all about how I saw it, rather than the song or even the lyrics. Because I remember thinking: the lyric doesn't mean anything to me.”

It’s one of This Mortal Coil’s most notable achievements. At best, Chilton’s lyrics are bland (“I first saw you/You had on blue jeans”), at worst they’re the language of a sex pest. Kangaroo appears to be about a guy perving over a girl at a party and unapologetically rubbing one out: “Thought you was a queen/Oh so flirty/I came against/Didn't say excuse/Knew what I was doing”. He puns on it later: He was doing a “cool, cool jerk,” he says. (Cool Jerk is a song from 1966 by The Capitols.) And then there’s the payoff: “I want you/Like a kangaroo”. Like a wha-? It’s surreal and a bit daft.

In This Mortal Coil’s version, Cinder subtly changes the lyrics, although she says it wasn’t deliberate, just Ivo writing them down wrong. Some sources have her as singing, “Thought you was uncool/Oh so floaty”, “I came again”, with “cool jerk” becoming “cool joke” but it’s not how she remembers it.

“I definitely sang, ‘Thought you was uncool/Oh so flirty’ and ‘I came against’ – it’s a big line in the song and I think if you listen closely as I hold the note it fades out with the ‘st’ very quietly at the end. It does sound as though in the mix they were fading that down as the note diminishes.”

Later, she says, “I’m singing ‘That same jolt, doing a cool cool jerk’.” The Chilton line is “That Saint Joan”. The demo of the song was originally called Like Saint Joan. “I’d forgotten about the Saint Joan reference,” she says. “That was definitely not on the lyrics that Ivo gave me, I was already interested in the historical figure by that point and would have leaned into that for sure.”

The original title of Big Star's Kanga Roo was Like St. Joan. “Saint Joan” was Joan Of Arc: a teenage girl who transcended gender roles, led men into battle and was tried, amongst other things, for the ‘blasphemy’ of wearing men’s clothes. She was burned at the stake.

Either way, This Mortal Coil’s version loses all sense of sleaze, and elevates mundane language to something else. Somehow, this song – this sleazy old wreck of a tune, transformed with bass and cello – sounds heartbreaking. It lacks literal lyrical meaning but somehow it sounds profound. A singer armed with empty words yet singing for his/her life.

“It's the emotions,” she says. “I always had a really shit memory. So, rather than making an arse of myself forgetting lyrics, I just learned to improvise and use the voice as an instrument.

“By this point, I was doing that all the time. I recorded the first Cindytalk album at the same time as we were doing This Mortal Coil.” To date, Cindytalk have had over a dozen albums of abstract and experimental noise-rock, with Cinder using her “voice as instrument”. “So I was in the studio, making this kind of raw energy record – it's not like songs are being written, it's just emotional content that's being shared in some sort of weirdly abstract but powerful way.”

It was a technique that found kinship in Elizabeth Fraser. “I mean, how the hell do you sing along with Elizabeth? The only thing you can do is play her at her own game,” she says. “Purely instinctively, you just throw your voice in, and move it around in the same space. If you sing along with her, then you're buggered. So you really have to be as daft as she was. So I had all of that inside of me.”

Cindytalk’s debut album was a primal scream – abrasive and brutal. “I didn't want to do anything too harsh with This Mortal Coil. I made a choice to go down a different path, to be more orthodox. But it probably still contains that raw emotion.

“It’s a human voice,” she says, “dealing with contours that they don't really understand – which, actually, is life itself. That's how we get by. We move through life, dealing with things. We don't quite know what's happening, and we have to figure out how to do it. So I guess that must have been deep inside when I recorded Kangaroo. Because the emotion works.”

It resonated. Jeff Buckley and Elizabeth Fraser were romantically involved in the 90s, but he was already a fan of her work and would doubtless have known about This Mortal Coil. He turned Kangaroo into a 14 minute epic he would play at live shows.

In 2022, indie rocker Jamie T used the music and the ‘chorus’ on his song 90s Cars. “That Jamie T thing,” she says. “He's attempting to put that same emotion into what he's singing. So it works. It's carried through over all the years. Crazy. I was taking a song, which had a destroyed sort of aspect about it, and bringing a whole another emotion.”

In a promo video, little seen in the days before MTV, let alone YouTube, Cinder/Gordon is dressed in black clothes, sometimes rock star cool in Raybans – a ‘young man’. During the middle eight, he’s cocooned in lace, and comes out more femme: dressed in white, hair down and long, holding flowers. It occasionally cuts back to the guy in black.

It's like Cinder/Gordon is both of the characters in Chilton’s song: the guy singing it and the object of his desire, the whole thing blurring so that they’re the same and it’s one male-female cry of yearning.

“I am pretty sure that I wasn’t playing out some kind of masculin/feminin switch play,” Cinder wrote by email, “although there does seem to be some weird subtext going on that dovetails with my own personal transgender narrative. I have heard it say that my voice appears to flicker between male and female. That has to be some kind of superpower…”

Back in 1984, I first heard Kangaroo not long after it came out, on a homemade cassette of the album. I thought it was sung by a woman. When I bought the single, I saw the credit to ‘Gordon Sharp’ and this androgynous figure on the sleeve…

“I was just about to say, ‘You were kind of right,’” she says. “I've always had that. I would say ‘non-binary’ because it doesn’t force you down one path or the other, it allows you to be sort of fluid and shift about and, you know, do your own thing and be unique, rather than sort of fitting into any sort of categories.

“I've had people come up to me and ask who the female singer is in Cindytalk, because they hear a male voice and a female voice. It's the same person, just shifting between the two – it’s natural for me to do that.”

I wondered if that's what you were expressing on Kangaroo, I say. When you say that it’s a mystery even to you what you were expressing – it sounds to me like this great showcase for a strong female-male voice. A voice that’s not one thing or the other, it’s both.

“It could be,” she says. “Maybe, deep down, I just wanted to share that. It's all pure instinct. I think the best music is.”

We had been talking about about Stuart Adamson and the Skids. Cinder’s band The Freeze supported the Skids around Fife in the late 70s. “If you go back to Stuart and his connection to the guitar in the early days of both the Skids and Big Country – that sort of earthiness – it's pure nature to us.

“You have no choice – but you don't really think too much. It's the thing that you express. We create our own little language. And if we're lucky it connects or if we're unlucky, then it remains, you know, just a sound."

Kangaroo is more than just a sound.

Cindytalk's music is available via their Bandcamp page. It'll End In Tears is available to buy and stream.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.