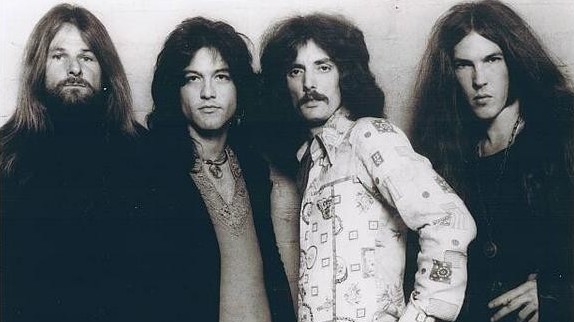

Rock’n’roll has many well-kept secrets, some dirty, some amazing, many both at once. It’s one of the genre’s most enduring and endearing traits. One of its greatest hidden treasures is a scruffy neo-supergroup from the dawn of the 1970s called Captain Beyond.

Formed in the wake of Iron Butterfly’s sudden and premature demise in 1971, Captain Beyond captured perfectly the zeitgeist of the era, wrapping their Technicolor freak-flag around the Butterfly’s grungey stoner metal, layering their dense caveman-thud with far-out spurts of space-prog and throbbing tribal grooves. It was hard rock, for sure, born of thunder and sweat, but it was weird and cosmic, too. Think head shops and UFO cults, and you’ve got it.

Captain Beyond were wily wizards gnawing on dinosaur bones in the waning days of the Age of Aquarius. It’s not surprising that Larry ‘Rhino’ Reinhardt is the only person that’s been part of Captain Beyond since the band formed. It was, after all, named after him.

“We were on tour in Europe with Iron Butterfly,” Reinhardt explains, sitting at home in Florida. “Butterfly and Yes were on the same bus. After a real long night with a pipe – we all partook in some attitude adjustment for the long ride – I was coming out of the bus, and Chris Squire from Yes looked at my blood-red eyes and said: ‘Goddamn, you look like Captain Beyond!’. The name stuck with me ever since.”

Reinhardt joined proto-metal warriors Iron Butterfly for their 1970 album Metamorphosis. He was also with them on a European tour to support the album.

“We were riding high, the European audiences were loving the new band. We were just tearing people’s heads off, and we were all saying: ‘We’ve really go to do another album’. But then Doug [Ingle, Iron Butterfly’s original singer] called a meeting, and so we went down there. As I remember it, there were a couple of groupies, and he was having a cocktail, and there were crosses all over the room. He was a preacher’s son, and I think he had a revelation or something. He said: ‘Guys, I can’t go on any more. I can’t take this rock ’n’ roll life with all the women and the drinking’. And I’m looking at him having a gin and tonic with two broads sitting next to him while he’s telling me this. I was in shock. I just couldn’t believe it. I was like, ‘This band is about to make a big, new splash, and you quit?’. We couldn’t do Butterfly without his voice. He flushed the toilet on us.”

After Butterfly ended, Reinhardt and Butterfly bassist Lee Dorman decided to continue playing together on a new project. Reinhardt called on an old friend to join them – drummer Bobby Caldwell. Caldwell and Reinhardt had played in rival garage bands in Florida in the late 60s. Caldwell later played with the Allman Brothers and with Johnny Winter’s band. He was still touring with Winter when he heard from the renegade Butterflies.

“They asked me if I wanted to get together. And I had been sitting on this idea since playing with the Allman Brothers. I wanted to do this different kind of music. I wanted to do something that was almost extreme but would also have real songs, just with different kinds of time signatures and arrangements. I’d been thinking about this for a long time, I just didn’t know if I could find the people to do it. So, I got this call from those guys. At the time, I was playing with Johnny and I was very happy. But then Johnny said he wanted to take a hiatus after being burned out from three years of very heavy touring. When that happened I flew to LA, and the three of us got together. And then Rod came in after that.”

In an interview in late 2012, Rhino suggested that Caldwell joined after Evans had been brought in:

“Our manager also looked after Rod, and suggested we try him out.”

Rod Evans was a founding member of Deep Purple, and sang on one of their biggest early hits, Hush. In 1969, Purple decided they needed a heavier sound, and so Evans was ousted from the band in favour of the leather-lunged Ian Gillan.

Looking for bright new horizons, Evans moved to Los Angeles. He soon found himself jamming with Captain Beyond. The results, according to Reinhardt, were both magical and miserable.

“Rod had a great voice and a great singing style,” he remembers. “Unfortunately he also had mental problems. He quit the band four times before we ever even hit the road.” Although Caldwell confirms Evans’ fight-or-flight behaviour, he doesn’t agree with Rhino’s assessment of his old singer’s mental status.

“Rhino’s right, he did quit a few times,” Caldwell says, “but I don’t think his behaviour had anything to do with mental problems. Rod was very insecure about his abilities, so any little thing would make him feel like maybe he wasn’t up to the job. That’s not very uncommon for people in the arts. As to what his insecurities were attributed to, I couldn’t tell you. All I can say is he was a great singer.”

Strained relationships within the band weren’t Captain Beyond’s only problems. Their first, self-titled album was a masterpiece of sophisticated aggression, part dope-rock thuggery, part limber, prog-baiting space-metal. It sold well, and the band gigged relentlessly, including a full-scale tour with the Alice Cooper band. But somewhere along the way, Beyond’s record label, Capricorn, had a sudden change of heart. According to Reinhardt, by the time the band starting working on their follow-up album, labelmates the Allman Brothers had broken big, and Capricorn wanted Captain Beyond to explore their southern side. Unfortunately they didn’t have one.

“We were in all the magazines – Rolling Stone, Billboard, all of that. Our record was in the charts and we were on the radio, but our record company just wasn’t behind us,” Reinhardt says. “They wanted us to change, to be more like them. We said: ‘You signed a blonde and now you want a brunette? We’re sorry, but we can’t just get a bottle of dye and change our hair colour’. That pissed them off, and that was the beginning of the end.

“They did everything they could to destroy us after that. That’s why, I think, we were like this sort of secret, cult band. They did stuff like put us on tours that were absolutely absurd, like Sha Na Na – they were headlining, we were the opening act. Does that sound good to you? We were playing in New York, in Central Park. It was like the Republicans and the Democrats, like going to Congress. When we were on, the Sha Na Na side of the crowd started throwing vegetables. They were throwing tomatoes, bananas and grapes at us, and we were trying to dodge all this shit. And then we got into the swing of it and we started to throw the vegetables back at them. And then the crowd started throwing stuff at each other. It just became a huge food fight. We called that one the Fruit And Vegetable Festival. It was just crazy. By the end of it we just started booking our own gigs, and the guy who owned the label was threatening to fly out and beat our asses. I offered to meet him halfway, so we could get it over with quicker.”

“I don’t remember it going down like that,” says Caldwell, who agrees that things got decidedly weird with Capricorn, but believes the reasons were less sinister, and more typical 70s rock bullshit: mismanagement and recreational drug use.

“What I remember is that we started having problems because our manager was also the head of the record label. It was a mistake. If your manager and the head of your record company is the same person, you can’t bring your grievances to either one. Also, there was so much… ‘stimulation’, let’s say, going on with the people at Capricorn, that they’d get on the phone, and any little thing could set them off. Phil [Walden, Capricorn head] threatened to kill Rhino, he threatened to kill Lee. There was this level of aggression going on, and things slowly started to deteriorate. I don’t remember it having anything to do with us playing southern rock, though. That wasn’t even on the cards.”

In 1973 the beleaguered band released their second album, Sufficiently Breathless. Combining the band’s penchant for spaced-out hard rock with a sudden affection for Latin percussion, the record is one odd duck indeed. A flop at the time it was released, the album eventually found its fans. Bobby Caldwell, who left the band before it was recorded, is not one of them.

“Around the end of 1972 there seemed to be a division in the band,” Caldwell says. “Lee and Rhino were on one side, Rod was sort of standing in the middle and I was on the other. And it was really probably about nothing important, just some childhood ego things or something. But we were really butting heads about something. And I remember saying: ‘Look, we’re right at the door of major stardom’. I knew we were going to break huge. I said: ‘All we have to do is keep doing what we’re doing. All we have to do is keep writing creative stuff’. But there was some kind of opposition mounting that was against that. So I finally said: ‘Fine. Fuck it. I’m leaving’. And I did. And that’s where you got the second album. Rhino found some new guys who would listen to him, and he turned the band into an all-gay Latin revue, or whatever it was [laughs]. If it was a great album, I would say it was. But it wasn’t. And it wasn’t Captain Beyond. It went nowhere.

“About seven months later, they gave me a call. I had just replaced Carmine Appice in Cactus, but I reconciled with the guys and we got back together, although I was very wary about the whole deal at this point.”

The band carried on, but Evans soon left the fold. To this day, neither Rhino nor Caldwell knows exactly why.

“We were getting ready to start the next album. It was just after Christmas, and Rod called a meeting and told us he was leaving the band,” Caldwell remembers. “There was no obvious underlying problems that we knew of for why he was quitting. It might have been his insecurities again, or because he had met a girl and maybe he didn’t want to leave her to go out on the road. Or maybe he was just outgrowing the band. I still don’t really know.”

With Evans’s departure, the band began holding auditions for a new singer – future Journey frontman Steve Perry was one of the many who ended up on the rejected pile – before they decided on a relative unknown, Willie Daffern.

In 1977, after several years of dealing with an indifferent record label and slowly building a cult of loyal listeners, the newly shuffled Captain Beyond released their third and final album, Dawn Explosion. Weird and wonderful, its comic-book prog-metal and ethereal space-streaking found the band in fine, freaky form. Unfortunately, they dissolved not long after the record hit the shelves.

“We were just starting to get somewhere – again,” sighs Rhino. “And then our singer, Willie, decided he wanted to go solo. And that was it. We kept trying to get it back together again but it just wouldn’t fly.”

“If I was just a drummer, and not a songwriter,” says Caldwell, “I probably would have cared a lot less about Captain Beyond breaking up. But I still feel like if we had just kept the band together we could have been huge. I mean, the band was already getting big. When we played Chicago it was like Led Zeppelin was playing there. That’s the kind of adulation that was going on. It was all there for us to take. We had the magic to make it all happen. We had the right songs and we had the right people, but we had the wrong manager and the wrong record company.”

With Captain Beyond on indefinite hiatus, Rhino decided to give some old friends a call.

“We got the original Iron Butterfly back together and went on tour. But by that point Doug was a completely different person. He’d pass out behind the keyboards, and suddenly you’d just hear ‘BRRRRRRRRRRR’, because he was laying on the keys. So that didn’t last. And then I didn’t play for about 10 years after that, because my hand almost got cut off. I fell out of a building doing security work. I fell about 30 feet. I went through two floors before I hit a bunch of boxes of wire. I didn’t even feel anything at first, but I was covered in blood, so I knew that wasn’t good. It cut two tendons in half on my left hand and almost cut a third one. They put 120 stitches in my hand. I used to cry. I’d pick up a guitar and I couldn’t even play a chord.”

Things went more smoothly for Caldwell. While on his first hiatus with Captain Beyond, the journeyman drummer joined Rick Derringer’s band, and played on his seminal All American Boy album. Caldwell later joined the short-lived Brit-rock supergroup Armageddon with former Yardbirds and Renaissance frontman Keith Relf.

Still, neither Rhino nor Caldwell felt like the Captain Beyond story was quite finished, especially since the band’s reputation as the godfathers of stoner rock continued to grow over the decades. And so, in the late 1990s, the band gave it one final try. Unfortunately they went out with a fizzle, not a bang.

“When Rhino contacted me about getting Beyond back together, I wasn’t too enthusiastic about it,” says Caldwell. “It didn’t seem like a very good idea. But I did try to get in touch with the other guys. I asked Lee, but he never called me back. There was something going on with Rod and Rhino, and Rod just didn’t want to deal with him. So, we had to get some new guys. We got a bar singer, and a bar bass player, and a guy on keyboards who thought he was Keith Emerson.”

This motley crew rolled into Sweden for the 1999 Sweden Rock Festival. But, despite a ravenous press and surprisingly warm and enthusiastic welcome, this potentially career-defining gig turned out to be a disaster.

“We didn’t play well,” sighs Reinhardt. “We couldn’t communicate with the sound guy. And amps kept blowing up.”

Caldwell remembers it differently: “Larry [Rhino] was drunk. He drank for two straight days before we even got out there. I could’ve picked him up and thrown him into the audience. That’s how mad I was. And I would have done it, if I didn’t think it would have broken up the band, as feeble as it was at the time. We’d been rehearsing for months for this show. Everyone was disappointed. There were so many people out there to see us, and he played so shitty, it was just a joke.”

Despite this major misstep, the band attempted to carry on for the next few years, and even released a four-track EP of new material in 2000. However, according to Caldwell it had become an endless struggle to keep things going. And in 2001 Captain Beyond played their final show together.

“We played a gig in the fall of 2001,” Caldwell remembers. “The place was sold out. It was in Clearwater. Florida. The people were packed in there and everybody seemed to be pleased. And then I didn’t hear from Rhino for two-and-a-half years after that. That was basically it.”

Bobby Caldwell still plays with his own band in Florida. As does Rhino Reinhardt, at the tie of writing. In fact after a long bout with liver cancer – and an exceedingly morbid 2009 solo album, Rhino’s Last Dance, for which Reinhardt sang his lines while wearing an oxygen mask – Captain Beyond’s guitar slinger has recently released a second [and decidedly more optimistic] solo album, Back In The Day. Assembling a crack band of local legends – most of the players on the record spent the last few years playing with former Allman Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts – Rhino’s resurrection album is a raucous wallop of southern-fried slabbage that touches on every aspect of his long and winding career, from Iron Butterfly’s sonic battering to Captain Beyond’s cosmic riffery to the gutbucket blooze that started Rhino on his musical path so many decades ago.

“It’s a bit of everything that I’ve done over the years,” he says. “The basic concept was playing music from my roots, going back in the day to the way things were, but with a modern edge.”

As for Captain Beyond, it appears that the good captain has launched his last cosmic voyage. Luckily, though, he is survived by countless young, long-haired, sufficiently breathless riff-addicts who have taken, and continue to take, inspiration from the band’s thunderous astro-prog.

“Captain Beyond is an acquired taste,” Caldwell admits. “But I’m telling you, when we were in Sweden for the Sweden Rock Festival, so many people were trying to talk to us that I thought maybe they had us confused with the Rolling Stones or something. Not that I haven’t had my share of people who want an autograph or to shake my hand, but in Sweden there was just so many of them. It’s still a worldwide phenomenon. To this day, Captain Beyond are still respected by listeners and by musicians.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock issue No.162 [cover date September 2011]. The following year both Larry ‘Rhino’ Reinhardt and Lee Dorman died. Reinhardt passed on January 2, 2012 at age 63 of cirrhosis of the liver; Dorman, age 70, died of natural causes in his car in Laguna Niguel, California on December 21, 2012.