The feelgood British summer of 1970 may have been one of hot, sunny days, with Mungo Jerry’s ubiquitous In The Summertime the defining song of its soundtrack, but it was also a year in which, along with the good vibes and warm zephyrs, some particularly chill winds blew through the rock music scene.

More than half a million revellers had smoked, toked, tripped and generally let it all hang out at the sun-kissed Isle of Wight Festival with a stellar line-up that featured The Doors, Free, The Who and Jimi Hendrix. But no matter how strong the IoW’s Yang, it was crushed by the Yin of events that included The Beatles breaking up and, on September 18, the bombshell that was Hendrix’s death.

On the upside in 1970, the 747 airplane had its first commercial flight, the Beatles released their final album Let It Be… and Caravan recorded their third album.

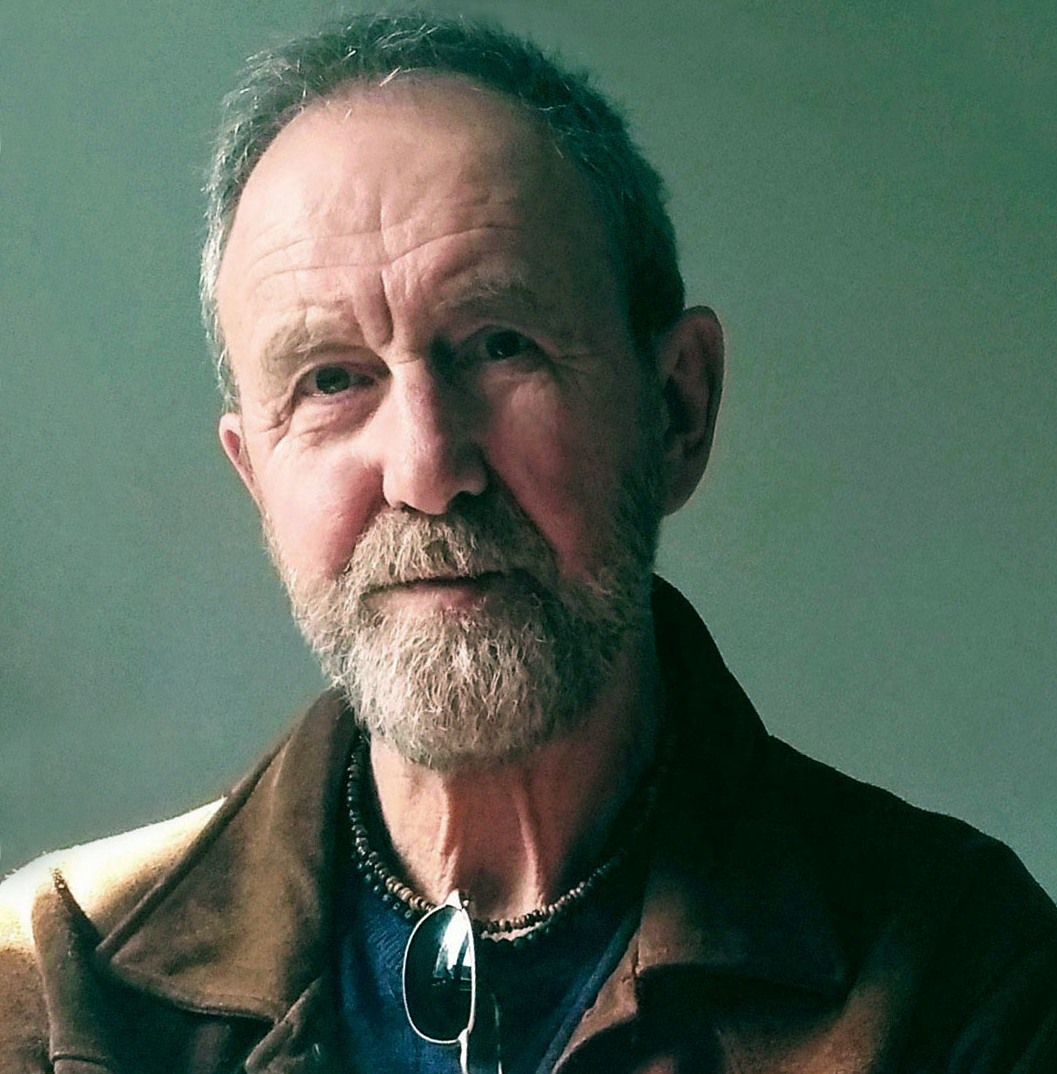

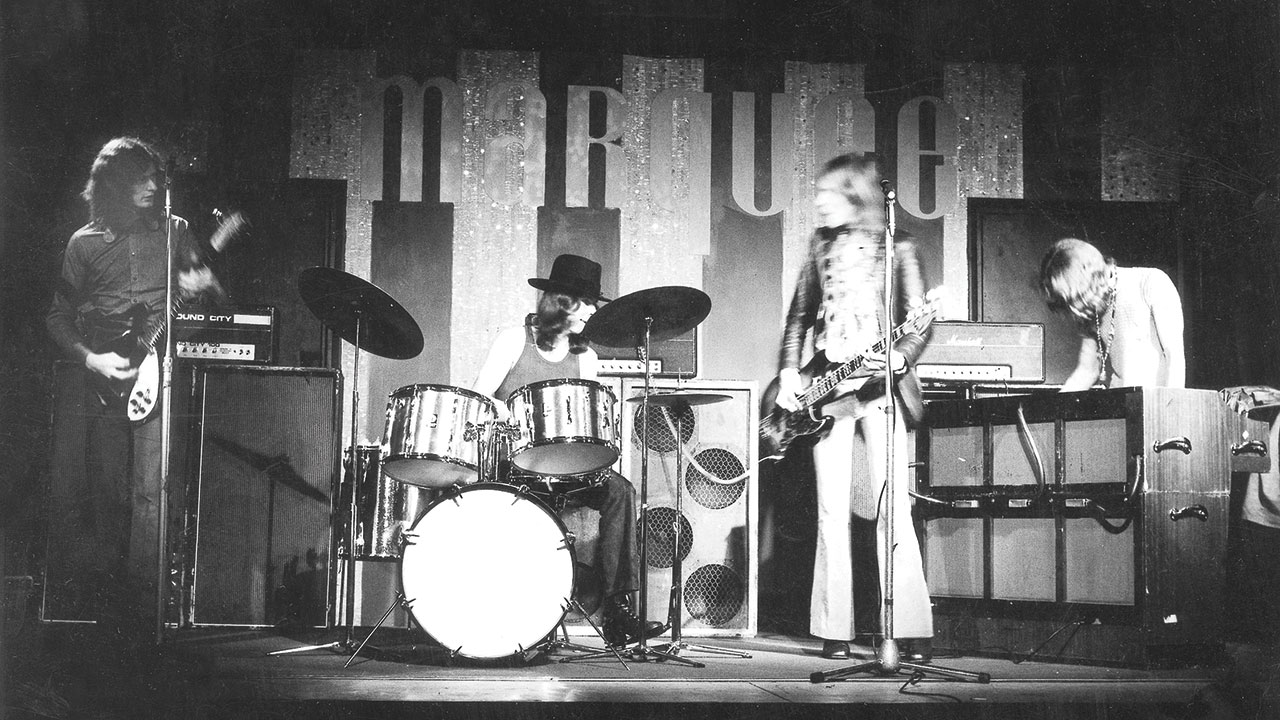

A four-piece from the sleepy cathedral city of Canterbury, decidedly English progressive rock band Caravan were major players in what came to be known as the Canterbury Scene. With three strong songwriters and two contrasting lead vocalists, Caravan had released two albums of highly original, inventive, accomplished and engaging music, yet outside the coterie of Canterbury Scene fans they remained largely unknown, their records acclaimed but not selling in numbers that would enable them to swap the out-of-date shelf at Tesco for the food hall at Harrods.

Caravan were arguably at a crossroads in late 1970. They may have been talented, but they were also skint. In fact their finances had improved little since two years earlier when, with not much more than fluff in their pockets, they’d spent the summer living in tents, happy campers until autumn’s falling temperatures forced them to seek shelter crashing with friends. It was a difficult time for the Canterbury Scene’s de facto leaders.

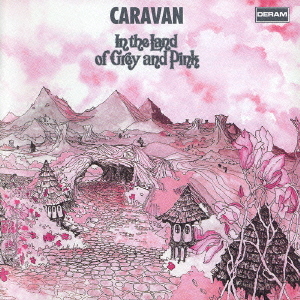

Cash-poor they might have been, but they were rich musically in terms of ideas and creativity. So much so that, after driving their van down to London and lugging their equipment into the creaky Decca Studios in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead one warm September day in 1970, they emerged one cold December morning from the smoky, darkened cocoon of AIR studios onto Oxford Street clutching the master tapes of what would be not only the greatest album of their career, but also a touchstone album of the Canterbury Scene and a progressive rock classic: In The Land Of Grey And Pink.

With their previous album, If I Could Do It All Over Again, I’d Do It All Over You, having been released earlier that year, there had been precious little time to write material for the new record. Much of the last one had been written by guitarist/vocalist Pye Hastings, which meant he now had little left in terms of fully formed songs. The only complete song he contributed to the new album was the jaunty Love To Love You, although he did, as did all of them, contribute ideas and bits and pieces for other people’s songs.

Hastings having written the lion’s share of If I Could Do It All Over… (and the band’s self-titled debut in ’68) also meant the others had material in their lockers. Bassist/vocalist Richard Sinclair brought along the dreamy, exquisite Winter Wine (“probably the best song Richard has ever written,” say both Hastings and keyboard player Dave Sinclair), along with the song that became the title track, and the bouncy Group Girl, later changed to Golf Girl and chosen to open the album. The Girl in question was Richard’s soon-to-be wife Trisha, who in the finished lyric became ‘Pat, and we sat… under a tree’.

“I believe we had all the music for the album before we went into the studio,” recalls Dave Sinclair now, “although I think some of the lyrics were left until the very last moment. In those days we always used to write the music first and the lyrics came later. On my Nine Feet Underground I wrote the lyrics for the Disassociation part and Richard sang that. For the second part, Love’s A Friend, I was having great trouble with the lyrics, and Pye helped me out quite considerably and he sang the song. Also, it was a higher part, and Pye had a higher voice than Richard.

“With Nine Feet Underground they were individual pieces, but with continually playing them through, and because each piece was only about five minutes long or something, I found it quite interesting to join bits up. I think it evolved, really. And this idea of doing one long number, I’d completely sorted it out well before we went into the studio. I was living in a basement flat at the time that was nine feet under ground level.”

Previously the band had ‘produced’ themselves. For this, their second album for Decca Records and first for new Decca imprint Deram, they were teamed with David Hitchcock, a Decca art department employee and aspiring producer (he’d worked on East Of Eden’s album Snafu and hit single Jig-A-Jig) whose genuine enthusiasm for Caravan and thrusting desire to work with them got him on board.

“For our first two albums we didn’t really have somebody who assumed a real leadership role and had that big, important strong influence on what we should be doing,” says Dave Sinclair. “David Hitchcock would tell us to try it again if he felt something wasn’t right, or try playing something a different way or whatever. He’d give us free rein, but he made sure he was getting what he wanted, basically. He was quite a hard taskmaster, which was what we needed.”

After three days of waiting around (“We just went to the pub,” admits Sinclair) while a suitably punchy sound was tweaked out of drummer Richard Coughlan’s newly acquired Hayman kit, it was down to business in earnest.

Although most of what would eventually make up the first side of the album – Golf Girl, Winter Wine, Love To Love You and In The Land Of Grey And Pink – was recorded at later sessions, in December, at George Martin’s recently opened state-of-the-art AIR studios, ‘prototype’ versions of some of those songs were the first fruits of the early Decca Studios sessions. One of those was a version of Winter Wine without lyrics, which got stuck with the title It’s Likely To Have A Name By Next Week and appeared on the 2001 expanded reissue of …Grey And Pink. From the same sessions, and another bonus track on that reissue, was Group Girl with ‘dummy’ lyrics.

Also recorded at Decca was Dave Sinclair’s Nine Feet Underground, a lengthy, adventurous piece of music in five parts, with linking sections. The completed version of this tour de force, which was to take up the whole of side two of the album, distilled the very essence of Caravan into 22 minutes and 40 seconds that would come to be one of the band’s defining moments.

Rather than save the most difficult until last, as most people would do, Caravan took the bull by the horns, and the whole of the Nine Feet… ‘suite’ was one of the first things they recorded at Decca.

“As far as recording Nine Feet Underground,” says Sinclair, “in those days if you made a mistake, if there was a big goof somewhere along the line, it needed major surgery to put it right. The fact of trying to play a 22-minute number in one go was… well, a lot of pressure. So we recorded it in sections and then David Hitchcock spliced it all together. It’s the only way we could do it, really. And for the whole album the recordings were done pretty much as live, apart from the odd overdub and solos that were put on afterwards.”

Unlike with most A&R departments, Caravan were lucky in that they didn’t suffer any interference from the label in terms of applying pressure to come up with singles material, passing judgement on early takes, or reminding the band that studio time was money. On the contrary, as well as keeping their noses out, Decca seemed happy to keep stumping up the money for an unusually lengthy period of recording.

“That was the amazing thing about it. We were virtually given free rein,” Dave Sinclair recalls. “At the time, it seemed like we had bags of time in the studio as well, so we could take our time. In fact I think that what happened was that they spent so much money in studio time that there was very little for promotion.”

They worked mainly in the daytime at Decca, and the night shift at AIR (“because it was above the Peter Robinson department store in Oxford Street, so you couldn’t record that much during the day,” Hastings explains), and mostly kept their noses to the grindstone.

“David Hitchcock was a very good influence in that respect,” says Sinclair. “The only going out, really, was to get equipment or something; there wasn’t much partying.” Even puffing on a fat one was employed as a creative aid rather than simply to get out of it. “It was just so I could focus on the music. I never smoked for recreation.”

Pye Hastings remembers that, remarkably, rather than staying in London and enjoying the nightlife and diversions that the capital had to offer, the “country boys” would pile into the van and drive the 60 miles back to Canterbury most nights.

“After Decca we’d sometimes go the pub and get pissed. AIR was about a three or four o’clock in the morning finish, and occasionally we’d go to the Speakeasy with Dave Hitchcock, who was a member there, and drive back in the dawn.”

After the final overdub, the final splice, the final mix, the band sat back and, for the first time, listened to their new album uninterrupted, in full. “And I absolutely loved it,” Hastings recalls. “After producing ourselves, it was a real eye-opener to work with Dave Hitchcock. If you’re on your own you can be a bit self-indulgent, everyone bringing up their own volume and things. So you need some sort of control. And David was brilliant. A huge amount of patience. Actually I played it about a year or so ago, after not hearing for at least 10 years, and I was quite impressed.”

Dave Sinclair: “We thought, ‘Well, we like it’. None of us were thinking, ‘I hope it’s going to sell lots, and whatever, and we need to get a manager who’s going to promote it.’ We didn’t even have a meeting, we were just, ‘Oh, that’s alright, isn’t it?’

“It really hit me when I was in a club in Canterbury called the Beehive. It was a late-night place and I would often go there. Not long after the album was released, I was in there one night and they put it on very loud. I think I’d had a little smoke or something, but I remember I sat back and thought, ‘Wow! This sounds really good!’”

In The Land Of Grey And Pink was released in April 1971 – with its now iconic gatefold sleeve featuring a beautiful, Tolkienesque ink/watercolour painting by artist Anne Marie Anderson (“We all just loved that so much,” Sinclair says, “and it seemed so appropriate”) – with barely an announcement, let alone to a publicity fanfare. Had Decca Records not been so laissez-faire with their studio-time money, perhaps, as Dave Sinclair said, there might have been something to promote the record with. Sadly Decca, having thrown caution to the wind, seemed to treat it with the kind of affection afforded an unwanted pet after Christmas.

Despite its muted arrival and – probably partly as a result of that – the fact that In The Land Of Grey And Pink failed to give the band their first sniff of the charts, it soon became Caravan fans’ favourite, and remains a much-loved classic of the Canterbury Scene into which it was born as heir to the throne. Ask any music fan these days to name a Canterbury Scene album and – if they can name one at all – it’s likely to be In The Land Of Grey And Pink. Ask those in the know to name the Scene’s best album, and you likely to get the same answer.

“Certain things just gel, just come together, don’t they?” the keyboard player says, looking for conditions that might have brought about Caravan’s, as well as one of progressive rock’s, Big Bangs. “You could say it’s in the planets, it’s in astrology. It’s in many things. The timing of it was just right, David Hitchcock coming along was just right, the music that we got together at that time, the way we progressed, was good. We’d reached a zenith, in a way. All bands try to get to a situation like that. We’d reached it.”