Had it not been for the in-fighting, the pressure, crap deals, ‘stolen’ songs and one control-freak member’s desire to run the whole show, Creedence Clearwater Revival might be remembered for more than just a handful of great singles.

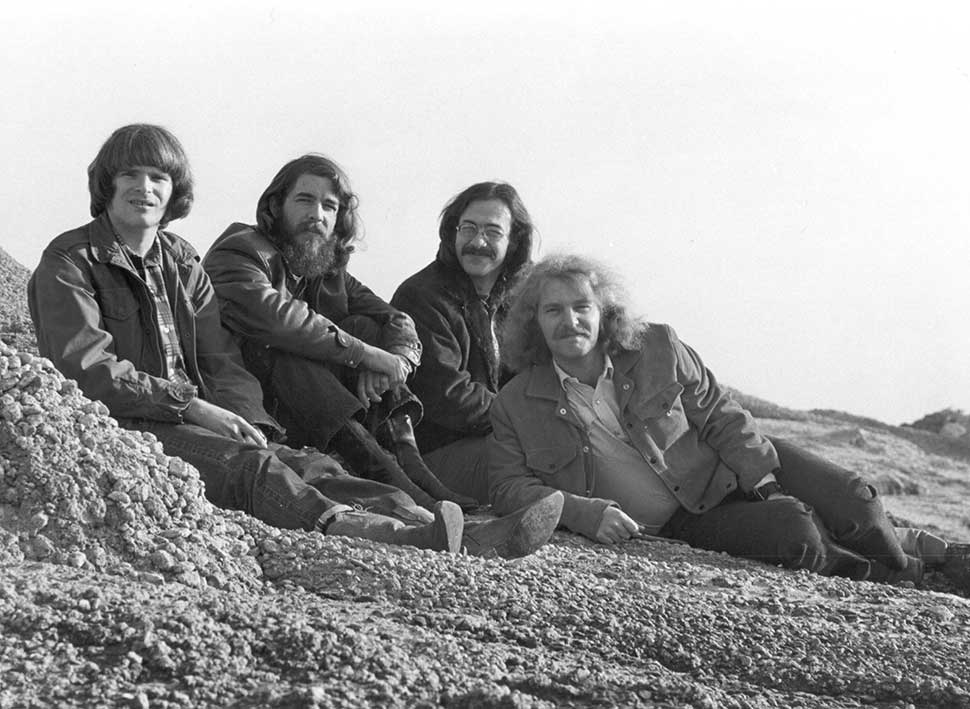

For three years between 1969 and 1971, Creedence Clearwater Revival were the hottest band in America. While the rest of the rock scene tripped through the turn of the decade wearing hallucinogenic glasses and rolling back musical boundaries wherever they found them, Creedence went in the opposite direction.

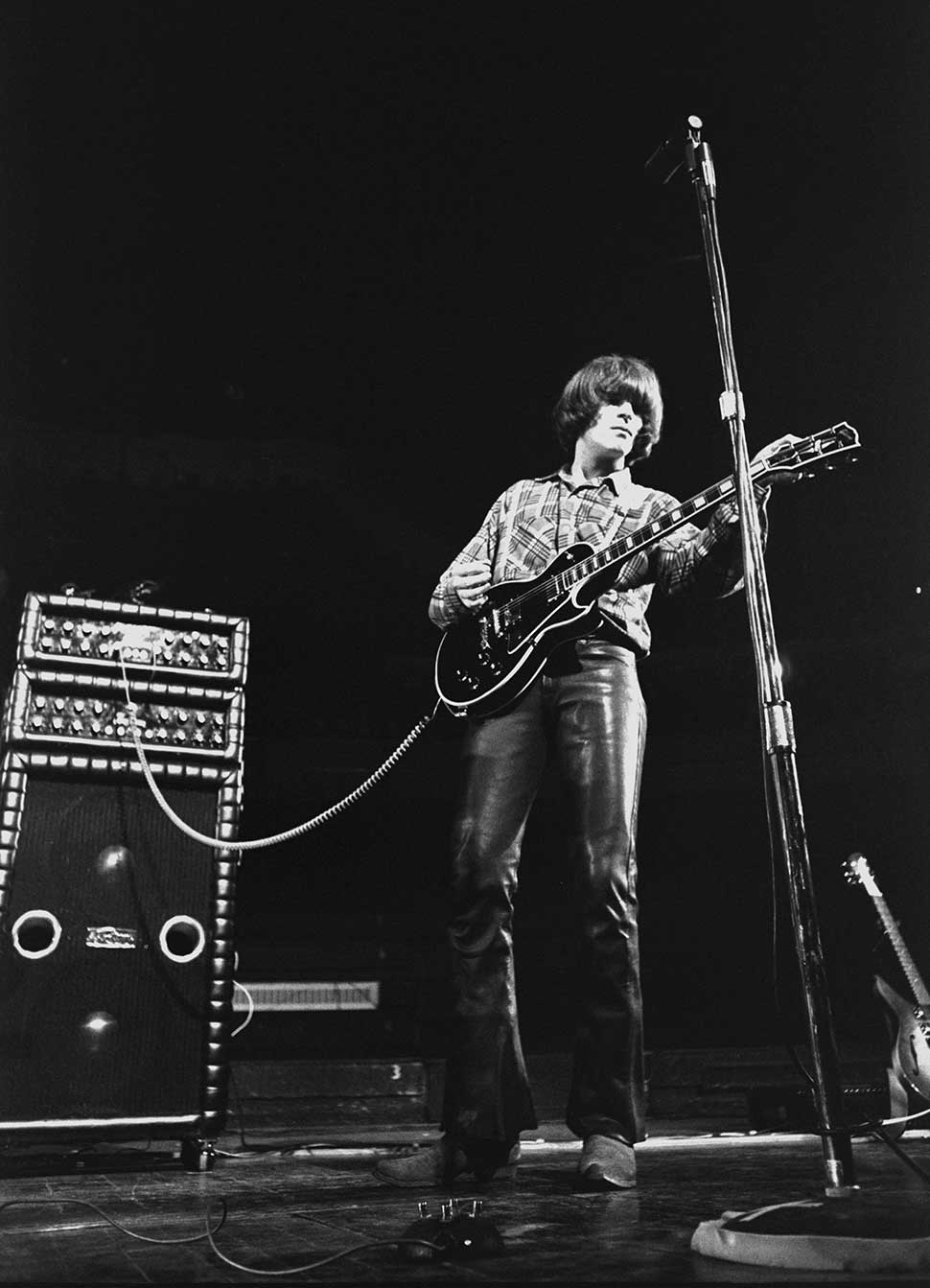

Led by writer, singer and lead guitarist John Fogerty, they headed back to the roots of rockabilly and rhythm & blues. Their songs, which conjured up the musical spirit of the American South, were simple, concise, hard-driving, evocative and catchy. The critics dubbed the band swamp rockers; in fact they’d never seen a bayou. They’d never even been out of their native California.

Creedence were not fashionable but they were hugely popular. They were hardly out of the charts, racking up 10 million-selling singles. Astonishingly, they never had a No.1 hit in America although they had plenty around the rest of the world, including the UK with Bad Moon Rising. To complete their saturation coverage they also churned out six Top 10 albums, half of them in a single year. Beyond that, Fogerty’s songs struck a chord with those concerned with the effect America’s war in Vietnam at that time was having on the country, let alone what effect it might be having on the Vietnamese.

John Fogerty broke up Creedence Clearwater Revival in 1972. Over the next 20 years he released three solo albums and had three Top 20 hits. But he was repeatedly involved in increasingly acrimonious lawsuits with Fantasy Records and its owner Saul Zaentz. And with a couple of exceptions he refused to play Creedence songs on stage.

In 1993 Creedence Clearwater Revival were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame. Bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug ‘Cosmo’ Clifford were in attendance (guitarist and brother Tom Fogerty had died in 1990), but John Fogerty refused to let them play. When he performed instead with a band that included Bruce Springsteen and Robbie Robertson, Clifford and Cook got up and walked out.

It was a sour Revival revival, and according to Doug Clifford just one more example of Fogerty “cutting off his nose to spite his face. I loved John like a brother. I still do. But I don’t like what he’s done to me, to Stu, to Tom’s widow, to his kids from his first marriage and, above all, what he’s done to himself.”

Creedence Clearwater Revival’s reign was brief and intense, but it was the culmination of 10 years of playing together.

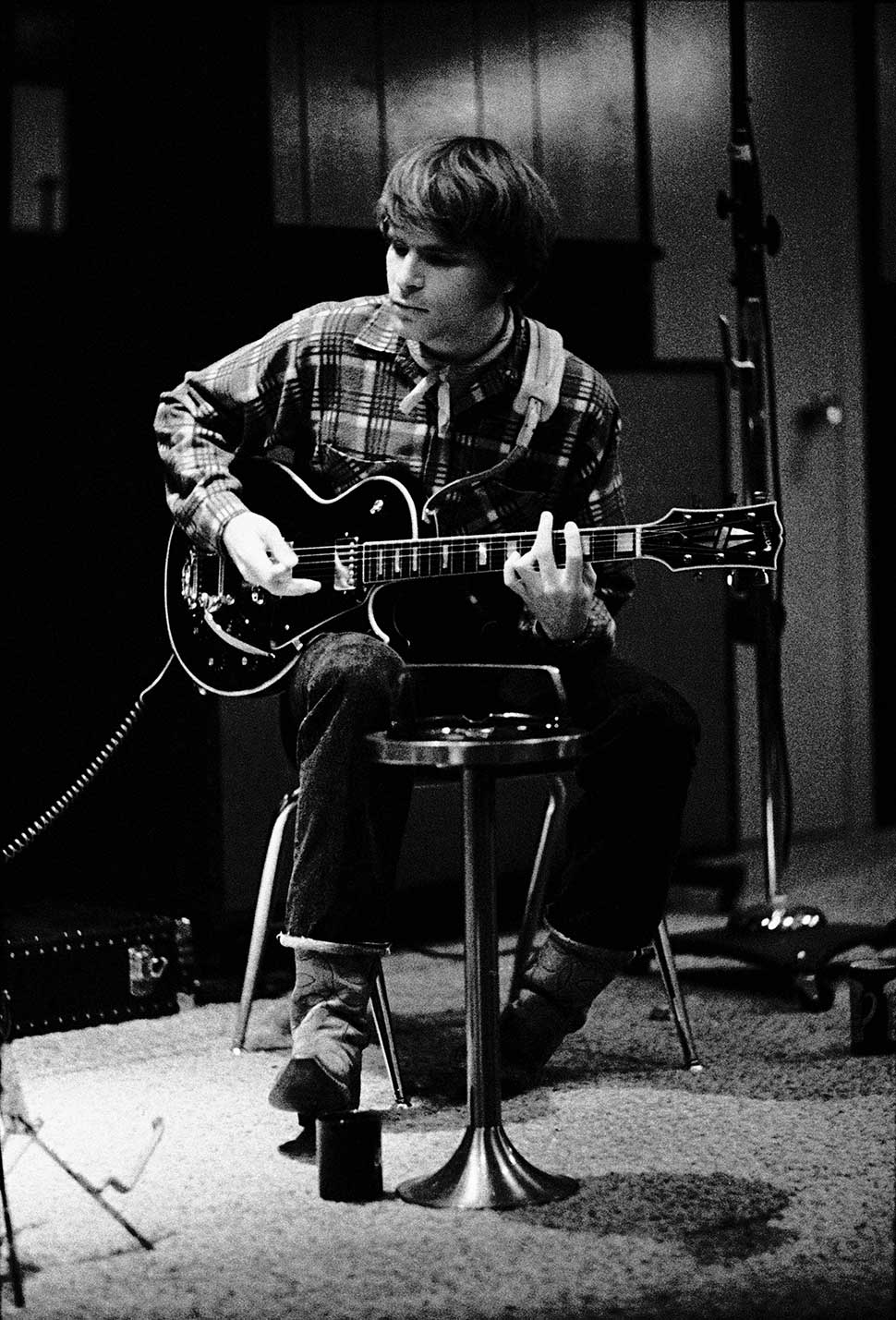

Clifford can still remember meeting John Fogerty for the first time in the music room at their Junior High School in El Cerrito, a dormitory town on the other side of the bay from San Francisco: “There was this shy kid playing Fats Domino on the piano. So I went up to him and said: ‘That’s authentic Fats.’ He said: ‘Yeah. What do you play?’ I said: ‘Drums. Do you want to form a band?’ He said: ‘Yeah, but actually I play guitar’.” They were both 14 years old.

They started out with Clifford’s friend Cook on piano; he switched to bass around the time they hooked up with John’s brother Tom, who was four years older.

“We were fledglings,” says Clifford, “but Tom already had the vision of a career and making records.” When they watched a TV programme about how a small independent label had an unexpected instrumental hit, they were interested to discover that the label, Fantasy, was just down the road in Berkeley.

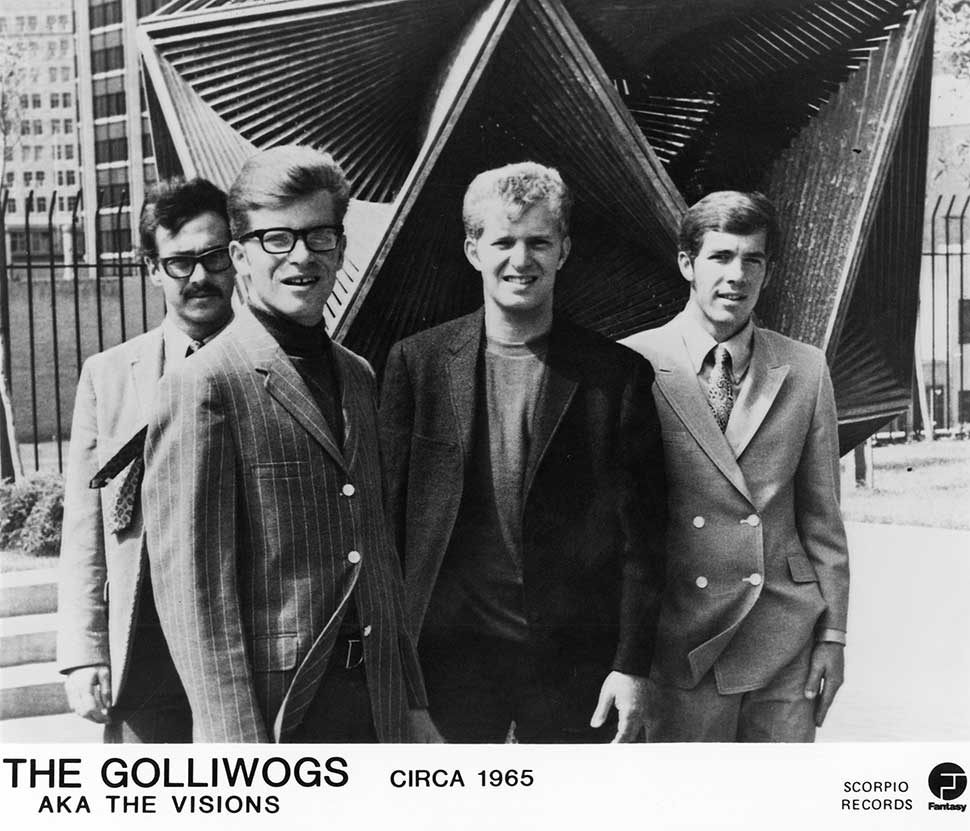

They hastily recorded an instrumental demo of their own and took it to Fantasy, which specialised in jazz records. The label asked if the band had a singer, because they were interested in signing a rock’n’roll band. No problem. Except that when they saw a copy of their first single they discovered their name had been changed from The Blue Velvets to The Golliwogs.

“We were shocked, particularly when we found out what it meant,” says Cook. “But we had to go with it because that was the name on the record label.”

At this point the band’s style was heavily influenced by British bands like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds and particularly Them.

It was around this time that John Fogerty started writing songs, initially along with his brother Tom and then on his own as his style came together. That gave them a distinctive sound of their own and they decided to pursue it.

“Tom was great about it,” says Clifford. “He was the ultimate team player. It took a lot of fortitude, particularly as he was the older brother and leader of the band, to give it up for his younger brother.”

After a temporary halt while Clifford and John Fogerty found ingenious ways to avoid the draft for the Vietnam war, they decided to go full-time in late 1967. They also renamed the band Creedence (“after a friend of Tom’s”) Clearwater (“from a beer commercial”) Revival (“a statement of intent”).

“We considered ourselves pretty professional already,” says Cook. “We had a real work ethic about the band. We rehearsed every day in a shed in Doug’s garden.” The shed was nicknamed Cosmo’s Factory.

They launched the band by re-releasing The Golliwogs’ last single, Porterville, with a new label stuck on the record.

The group eventually got their break with an edited version of Dale Hawkins’s Susie Q that spread by airplay and only just missed the Top 10. Radio stations in the US were looking for snappy commercial rock to counteract the rising tide of mind-expanding music whose spiritual home was just 20 miles across the San Francisco Bay.

But to Creedence – living in California’s answer to Woking – it was a world away. They mostly had wives or steady girlfriends, and spent the fabled summer of love in 1967 ploughing away on the local circuit. The hippies’ heaven in Haight Ashbury was as alien to them as it was to their parents. “We’d been brought up on Top 40 radio, where the song was the thing, not the guitar solo,” says Cook. “You told the story and then you were done. And that was John’s real skill, to be able to write songs like that.”

Nevertheless, it was still a thrill to play their first gig at the legendary San Francisco Fillmore in the summer of ’68, supporting Paul Butterfield and Steppenwolf. “We played four nights and got 16 encores,” recalls Cook proudly. “The hippies loved it because they could dance to it.”

What Cook calls “the great gush” started in March 1969 when Proud Mary (from their second album, Bayou Country) became the first of five No.2 hits, with the riff rolling as powerfully as the big wheel kept on turning. Radio was primed for the band, and John Fogerty had found his songwriting range – plus the voice to match.

“We just went in and did it,” says Cook. “It felt automatic. It was just how we played together. We’d learned the songs thoroughly. There wasn’t anybody else in the studio pulling strings, just the four of us.”

Two months later they did it again with Bad Moon Rising. They didn’t object to the ‘swamp rock’ tag either. “That was okay,” says Clifford. “At least it meant people cared enough to make up labels. We used to chuckle about it, particularly when people thought we came from Louisiana.”

The band spent a lot of that summer playing big festivals: the Newport ’69 Pop Festival with Hendrix and The Byrds, in front of 150,000; the Denver Pop Festival with Jimi Hendrix and The Mothers Of Invention; the Atlanta Pop Festival with Led Zeppelin and Joe Cocker in front of 120,000; and the defining festival of them all, Woodstock.

Green River was their third No.2 single on the trot, in August 1969, and the album of the same name finally gave them a No.1 record in America a month later. By the end of the year they’d had more hits with Down On The Corner and Fortunate Son and were storming up the album charts again with their fourth album, Willy & The Poor Boys. It was a feverish pace.

“John was convinced that if we weren’t in the charts the public would forget about us,” says Clifford. “So after we’d recorded three singles – that’s six tracks – we’d go into the studio and record four more tracks to make up an album. That put a tremendous amount of pressure on John, but he was able to do it.”

Musically John Fogerty was going from strength to strength. But behind the scenes things were beginning to fracture. Clifford and Cook maintain that the problems began with John’s insistence on managing the band as well as writing, singing, playing and producing. “John was brilliant at all the musical things, but he had no experience at managing, particularly at the level we were involved at,” says Clifford. “It was a critical mistake, and ultimately it broke up the band.”

Creedence had signed the usual slavery deal for an unknown band, but Fantasy were now prepared to re-negotiate. John Fogerty had also signed a separate publishing contract with Fantasy. “I think that John believed he would get his songs back after his three- year deal, but this was not the case,” says Cook. “He was simply free to sign a new contract or set up his own publishing company.”

Clifford and Cook claim that Saul Zaentz made promises to Fogerty and the rest of the band that he subsequently reneged on, but their involvement with even the band’s contract was strictly limited. “We were not allowed to go to meetings. And John wouldn’t communicate with us afterwards. Once it started to go sour he dealt with it on a very personal level, and that resulted in a shut-down.”

According to Cook and Clifford, the band were offered a deal that would have given them 10 per cent of Fantasy Records – effectively 10 per cent of themselves, as they were the only the only chart act on the label. “John said it was nearer one per cent, but I don’t think he understood about stock options and stuff,” says Clifford. “And he was doing it all himself. He didn’t seem to be taking advice from anyone. There were lawyers, but they could only deal with what he communicated to them so that wasn’t much help.

“We could all see that it was driving him nuts. We were there as bandmates, and with ideas to try and help him out of this log-jam, but he just got more and more withdrawn, as if we were attacking him. It was very frustrating.

“I suggested that we should go out on a world tour for a year and work on a couple of albums’ worth of songs along the way, meanwhile we’d get a team of professionals to come in and sort out the mess with Fantasy. Then we could come back with a new deal and hopefully resolve John’s songwriting deal. But John said people would forget us. I felt that a world tour would keep us in the public eye.”

When Fogerty threatened to bring in the notorious Allen Klein – who was busy making mincemeat of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones (and their labels) – the others backed off in horror.

They did a tour of Europe in spring 1970, playing London’s Royal Albert Hall with Booker T & The MGs. And the hits kept rolling in: Travellin’ Band, Who’ll Stop The Rain, Up Around The Bend, Lookin’ Out My Back Door. Their fifth album, Cosmo’s Factory, spent nine weeks at No.1.

But contract negotiations with Fantasy had come to a standstill. And now there was another problem looming: “Tom had graciously stepped aside to let John try his new way with the band that turned out to be so successful,” explains Cook. “But now he wanted to be more involved musically. He felt that it wouldn’t hurt the band if he got to sing a song on the album. My attitude was: ‘Let’s see if Tom can contribute something. Let’s not pre-judge it and just say no.’ But John wasn’t going to give him any room.”

This situation deteriorated. Clifford says Tom threatened to quit several times during 1970, and that he and Cook would go round and talk him out of it. In February 1971, just after the release of their Pendulum album, Tom Fogerty made good his threat.

Creedence continued as a trio. They toured Europe again, and Australia and Japan. But Cook describes that year as “pretty miserable”. And within the business people were increasingly aware that all was not well with the band. The rest of the world found out in May 1972 when they released the Mardis Gras album. The songs were divided equally between Fogerty, Clifford and Cook. For Clifford and Cook it was the first songwriting credits they had had. And it showed.

Read any account of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s story and they all state unequivocally that Fogerty bowed to pressure from Clifford and Cook for an equal writing share on the Mardis Gras album. Those accounts then invariably follow that up with an excoriating attack on the album.

Clifford and Cook completely deny this version of events: “It was the complete opposite to that,” Cook says. “Tom may have wanted to contribute songs, but Doug and I never wanted to. But John told us – this was in the limousine after the last gig of a tour before we’re having a break – that we would each do a third of the songs on the next album. And he would not be singing on our songs because his voice was ‘a unique instrument’. He didn’t even play guitar on them.

“I said: ‘That’s not what we want. And Creedence fans are not going to understand this.’ And he said: ‘If we don’t do it this way, then I’m going to quit right now.’ He knew we couldn’t do anything without him, and in retrospect we should have finished then, but at the time we didn’t want the band to break up. Artistically that was a mistake, but we felt we were trying to save the band.”

They couldn’t save it for long, though. In October 1972, five months after the Mardis Gras album (which still reached No.12), John Fogerty disbanded Creedence Clearwater Revival, publicly citing Mardis Gras as a reason. “He came round to my house and told me: ‘I’m quitting’,” says Cook. And I said: ‘At this point so am I. I’ve had enough.’”

Clifford and Cook were released from their contracts with Fantasy (the contracts that had never been renegotiated). Fogerty was not released from his contract. His next album, the following year, was called John Fogerty/The Blue Ridge Rangers. There were no Blue Ridge Rangers – Fogerty sang and played everything on this collection of country covers. It was good but it wasn’t what John Fogerty fans were expecting and country fans were still redneck enough to be suspicious of anyone who had questioned the Vietnam war.

Still, he had a Top 20 hit with his version of Jamablaya (On The Bayou). But Fogerty claimed that Fantasy did not promote the record properly, and demanded to be released from his contract. Fantasy said no. The contract still had eight albums to run. Fogerty refused to record any more songs, so Fantasy sued him for breach of contract.

Fogerty’s hit pedigree was bound to attract other record companies, and eventually David Geffen’s Asylum label secured the North American rights to Fogerty’s next album for $1million dollars, leaving Fantasy with the rest of the world. Fogerty managed to get out of his publishing contract by forfeiting all rights to the songs he’d written so far.

His self-titled solo album came out in 1975, and was Creedence Clearwater Revival without the band – quite literally. The critics loved it but the public was less enthusiastic. The album never charted, although Fogerty did manage a Top 30 single with the opening track, Rockin’ All Over The World. But it did nothing in Britain. And even Status Quo were in two minds before they recorded it a couple of years later.

Fogerty threw himself into another album, but even though he was now free from his Fantasy publishing contract the loss of his Creedence songs gnawed away at him.

One week before Hoodoo was due for release, Fogerty withdrew the album. Asylum – who had already had their fingers burned with the previous album – had told him it was below standard. Fogerty closed down for the next 10 years.

Clifford and Cook, meanwhile, had dusted themselves down and found employment with Doug Sahm, whose style suited them perfectly. Clifford produced Sahm’s Groover’s Paradise album in 1974. They then joined the Don Harrison Band for three albums in 1876/77. And Cook produced legendary acid casualty and leader of the 13th Floor Elevators Roky Erickson, taking him out of the mental asylum on a daily basis and recording him as his medication wore off and before the resulting weirdness took hold.

Tom Fogerty had also been releasing solo albums on Fantasy but only the first had come within 20 places of the Top 100. If Fantasy were concerned about what had happened to the goose that had laid their (one and only) golden egg they tried not to let it show. Any time anybody there had a spare half hour they’d compile another Creedence collection. Their care and devotion to the Creedence legend was evident from the 1981 live album The Royal Albert Hall Concert, which was actually recorded at the Oakland Almeida County Coliseum.

There were two Creedence Clearwater Revival reunions during this time. The first was at Tom Fogerty’s wedding in 1980 – “It was a short set, and there was no doubt that Tom was still consumed by bitterness,” says Cook. The second was at the El Cerrito High School Reunion for the Class of ’63 (without Tom) when they took over, unannounced, from the house band – “It felt and sounded great. And I thought John might be getting over his bitterness, but I was wrong”.

The others were included in the bitterness because they were continuing to deal with Fantasy. “We were dealing with Fantasy,” confirms Clifford. We were auditing them repeatedly. And we were trying to get a better deal. They still had all our records.”

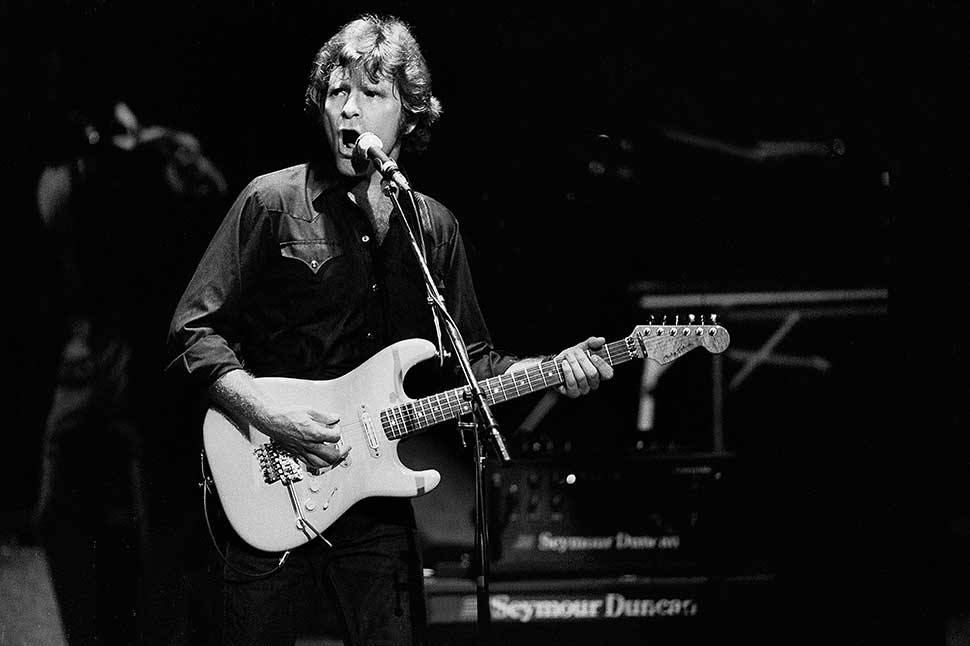

In the mid-80s Fogerty was lured out of retirement – this time by Warners – and delivered what is regarded as his strongest solo album, Centerfield, which went to No.1. But despite this triumphant return he was still able to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

Two of the tracks on the album were Zanz Kan’t Dance and Mr Greed. The video for the former featured a clay animation of a little guy singing: ‘Zanz kan’t dance but he’ll steal your money/Watch out boy he’ll rob you blind’ while a large naked pig proceeded to pick- pocket the audience. There was no video for Mr Greed, but the sentiments were similar.

Fearing they would be sued, Warners told Fogerty to remove the tracks. Fogerty refused, and indemnified Warners instead. He then found himself facing a $140 million defamation lawsuit from Saul Zaentz. Scarcely had he wriggled out of that by changing the song title to Vanz Kan’t Dance than Fantasy sued him, claiming that the album’s first single, The Old Man Down The Road (not published by Fantasy), plagiarised an earlier Creedence song, Run Through The Jungle (published by Fantasy). Fogerty was being sued for plagiarising himself.

It was a bizarre scenario and Fogerty found himself in the witness box with his guitar, demonstrating to the jury how two songs by the same writer could sound the same and yet be different. He managed to convince them, but it took 10 years to retrieve his legal costs of $400,000.

Tom Fogerty died in 1990 of respiratory failure, the feud with his brother unresolved. Clifford and Cook thought they might be able to resolve their feud when Creedence Clearwater Revival were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame in 1993. They were invited to the ceremony and told they would be playing in the all-star jam. But when Clifford turned up and asked which was his drum kit he was told by a stagehand that they weren’t playing at all, and that John had been rehearsing with Robbie Robertson and Bruce Springsteen and the house band for the past month.

In 1995 Clifford and Cook set up Creedence Clearwater Revisited, initially with The Cars’ Elliot Easton on guitar. But Fogerty issued an injunction over the name, and for a while they went out as Stu Cook and Doug ‘Cosmo’ Clifford Present Cosmo’s Factory – An Evening With Creedence.

“You could scarcely fit it on a ticket,” says Cook.

“John maintained that the trademark could only be controlled by unanimous decision. We said it was a majority, and the court saw it that way. In the end we settled for money, which didn’t seem to be about saving the name or preserving the honour of his creations.”

They could in fact use the name Creedcence Clearwater Revival if they wished, but “we chose not to out of respect for the original band and to avoid unnecessary confusion with our fans,” Cook says.

Fogerty has preserved the honour of his creations mainly by not playing them. He claimed he was prevented from doing so, although that didn’t seem to prevent anyone else from playing them. When he finally played a bunch of Creedence songs at a benefit show for Vietnam veterans in 1987 it was a newsworthy event.

Since 1995 Fogerty has included Creedence songs in his concerts, and signs began to appear that he might be resolving his feud with himself. In 2004 Saul Zaentz sold Fantasy Records to Concord Records, and the following year John Fogerty re-signed to Fantasy Records, thus reuniting himself with himself.

Concord president Glenn Barros stated: “John would like to own his songs, and unfortunately we can’t do that because we just paid a lot of money for them.” But Barros did restored the songwriting royalties that Fogerty gave away back in the 70s.

“That was a wonderful first step,” responded Fogerty.

Concord also released a collection called The Long Road Home, which was the first time Creedence songs and Fogerty solo songs had appeared on the same CD. Fogerty was involved in compiling the album, so it’s perhaps not surprising that among the 25 tracks were The Old Man Down The Road and Run Through The Jungle. The good news for Concord was that Vanz Kan’t Dance and Mr Greed were conspicuous by their absence.

And, in early 2023, Fogerty finally got what he'd battled for for half a century. He bought a majority stake in the rights to the Creedence catalogue from Concord, gaining control of his own work once more.

"This is something I thought would never be a possibility," he tweeted. "After 50 years, I am finally reunited with my songs."

This original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock #89, in February 2006.