"There was more sun shining in Trespass… We’d gone indoors.” Genesis and the story of Nursery Cryme

With new drummer Phil Collins and guitarist Steve Hackett bolstering their ranks, Genesis pushed the boat out with album No. 3

As the many retrospectives of the music of 1971 play out, Nursery Cryme, the third studio album by Genesis, is now resolutely included. However, unlike many other records being celebrated, Nursery Cryme, outside of certain pockets in the UK, and fortuitously, Italy – was barely known at the time.

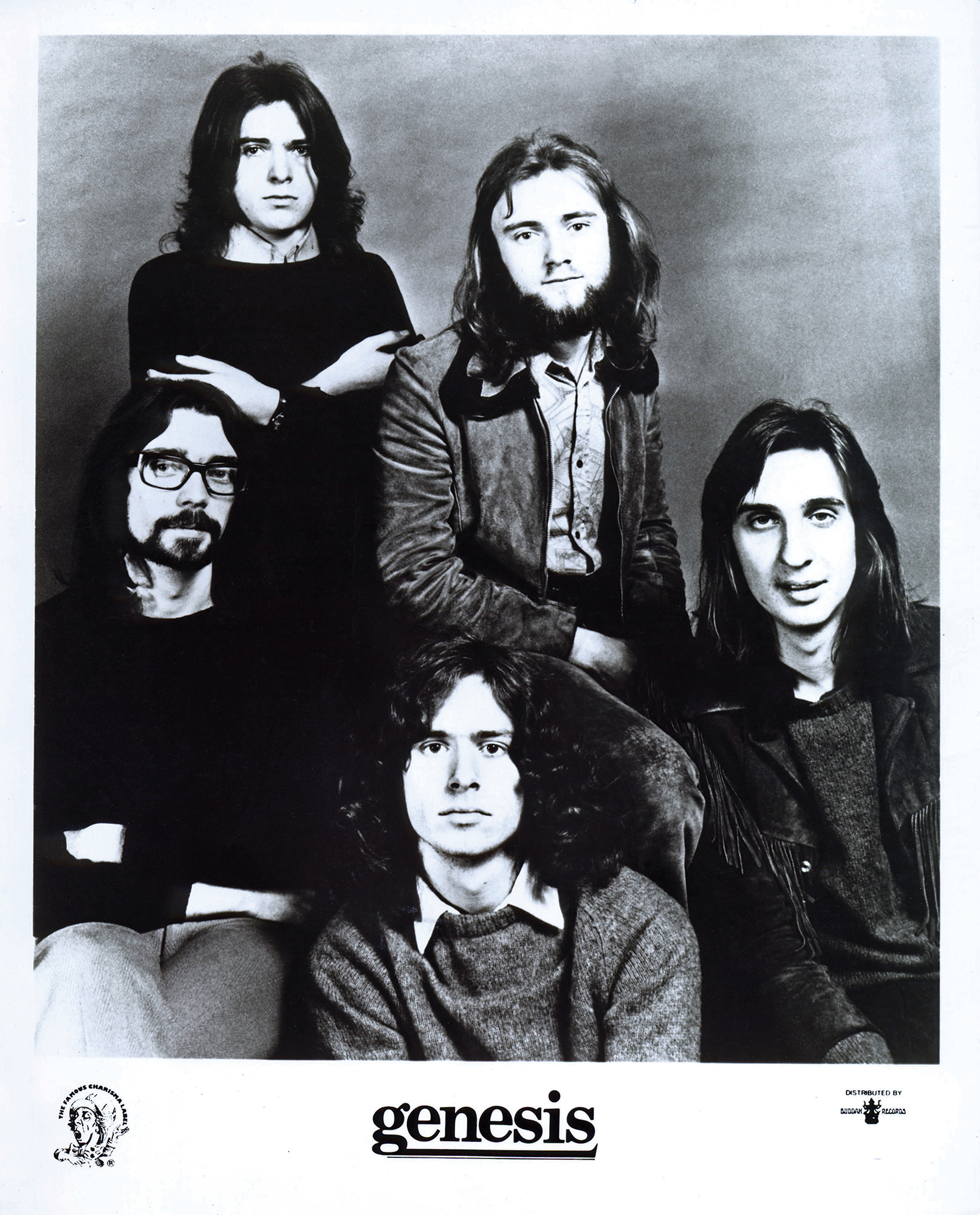

It nestled at No.39 in the UK Albums Chart for one week, but that wasn’t until May 1974, in the mild outbreak of Genesisteria that arose after the UK Top 30 single I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe) and the success of Selling England By The Pound. But, back in 1971, Genesis were a niche within a niche, and although their new line-up – the album marked both Phil Collins’ and Steve Hackett’s debut – suggested a new stability, with the lack of commercial success, the group seemed forever teetering on the brink of collapse.

Conceived in an old, decommissioned maltings in Farnham, of “bare floor-boards

and pigeon shit,” prepared in a cramped rehearsal room in West Hampstead and fleshed out at a luxurious country house in Sussex, Nursery Cryme is arguably the most important album in the group’s catalogue. It signalled the change in direction in their music, and revealed that they could survive without creative force Anthony Phillips. It was, in the words of Peter Gabriel, “a step into the shade… there was more sun shining in Trespass… we’d gone indoors.” Although Nursery Cryme isn’t artistically or creatively the best album by Genesis, the contributions of Collins and Hackett, however tentative at this stage, were to leave an indelible mark on the outfit.

Nursery Cryme also took Genesis away from the overtly biblical connotations of the first two albums, that had famously seen From Genesis To Revelation allegedly filed in the religious sections of record shops. Even though 1970’s Trespass was less overtly holy, its title was still taken from The Lord’s Prayer with its visions of angels. Decapitation by croquet mallet, rampantly charging weeds and suicidal fat men were among the resolutely unconventional subject matter this time out. “It was a revolutionary year for me,” Steve Hackett says today. “Lots of my dreams were coming true. The year of becoming 21: the key to the door and the key to the universe of music, frankly, and I thought, ‘Thank Christ for this. I know what I’d like to be doing for the rest of my life.’”

“It’s incredible how young they were to be creating that music,” adds friend and road manager Richard Macphail.

It’s well documented in Genesis lore quite how devastated the rest of the group were when co-founder, guitarist Anthony ‘Ant’ Phillips left the group after the show at the Sussex [now Clair] Hall in Haywards Heath on July 18, 1970. Trespass, their second album, and the first for Charisma, had been recorded that June and wouldn’t be released until October.

After much contemplation and encouragement from Macphail, Peter Gabriel, Tony Banks and Mike Rutherford decided to continue, advertising not only for a guitarist but also a drummer as the watershed had provided an opportunity for their third percussionist, John Mayhew, to move on. After seeing their advert in Melody Maker, ex-Flaming Youth drummer Phil Collins auditioned; he arrived early at Gabriel’s parents’ farm in Chobham that August, with his guitarist friend Ronnie Caryl, and went for a swimcin the pool while he heard the other drummers play. By the time it was his turn, he was familiar with what he’dcbe asked to perform. Caryl auditioned for the guitarist’s role. Collins was successful but Caryl, being too bluesy, was not. Gabriel was to say, “I knew when Phil sat down on the kit, before he played a note, that this was a guy who really was in command of what he was doing, because he was so confident. It’s like watching a jockey sit on a horse.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

After a handful of summer shows and the impending release of Trespass, Genesis – with new drummer Phil Collins – returned to the road at Chatham’s Medway Technical College on October 2, 1970. The group had rehearsed extensively at the Farnham Maltings near Rutherford’s parents’ home in Surrey.

“We just couldn’t replace Ant,” Macphail says.

“The nature of the guitar is that it tends to attract people who like to be flamboyant and out there making a lot of noise as the centre of attention,” Tony Banks says. “We were looking for exactly the opposite of that.”

“Gigs were in the book, so we went on as a four-piece,” Macphail continues. “Charisma’s Fred Munt suggested that we get a Hohner electric piano with

a fuzzbox, and put that on top of the organ. That was the beginning of Tony’s multi-keyboard thing.”

New roadie Paul Davidson – lured away from university for a life on the road by Macphail – was there that night: “Phil needed quite a lot of attention because at that stage, he hadn’t got a drum board, so his kit was always moving around. Part of my job was making sure it didn’t move around too much by a putting couple of nails into the stage.”

“When Phil came in, he could do a tap dance on stage,” Charisma PR Glen Colson says. “He was made for showbiz. He still is.” It was during this brief period as a four-piece that Banks, Collins and Rutherford truly gelled, establishing a musical telepathy between them that exists to this day.

“We literally left Ant’s amp on stage right and took a long lead and plugged the electric piano into it,” Macphail recalls. “Tony would play Ant’s solos on the repertoire that was being played live at the time.”

Collins’ pal Ronnie Caryl played guitar with them at a show in October, before Mick Barnard was drafted in; he played at gigs from November to January 1971. It was Genesis’ Friars Aylesbury champion, David Stopps, who suggested that Barnard join. Stopps knew him from local band The Farm. “He helped them out at that moment,” Stopps says. “When Peter asked me if I knew anybody, I thought of him.”

“Mick was much more of a member than Ronnie,” Richard Macphail says. “He was quite quiet, a good player, no doubt about it.” Although Barnard was with them, the search for a permanent guitarist went on: “They didn’t just need an axeman, they needed someone who was more than that,” Macphail adds.

Gabriel was intrigued by an ad he saw in Melody Maker on December 12, 1970 – “Imaginative guitarist-writer seeks involvement with receptive musicians, determined to strive beyond existing stagnant music form.” Gabriel phoned Hackett and suggested he listen to Trespass and come and see the group live.

Hackett went with his brother John to see Genesis – with Barnard – play at London’s Lyceum on December 28. “They seemed almost like a semi-acoustic band. They started with Happy The Man: I thought I was supposed to be seeing a rock band,” Steve Hackett says. “I realised that there was as much acoustic music in this as there was rock. They were different from most bands in that way.”

As 1971 dawned, Banks and Gabriel went to Hackett’s flat in Pimlico. “They said they had a guitarist, but they wanted someone who not only played electric, but 12-string as well,” Hackett says. “I was a huge fan of the 12-string. I played them a number of things in different styles. It was very interesting, Pete did all the talking. Tony [Stratton-Smith] didn’t say a word.”

Hackett was asked to join, and out went Mick Barnard. There was little doubt that Bernard was a good player who had helped the group immeasurably. “In a way, looking back, they really were waiting for Steve,” Macphail states. “Steve had so many other irons in the fire because he was into unusual tunings, 12-string acoustic and all that stuff.”

Many were to wonder what happened to the missing Genesis player. “Mick was a local legend. He was and still is a brilliant blues player. He’s still playing today,” Stopps says.

Steve Hackett brought his intense musicianship with him. As Gabriel was to say, he was “the colouring agent, dark contained personality that was struggling to get out. Yearning, looming build-up of compressed energy. Steve had a dollop of unfulfilled frustrations.”

Charisma Records – guided precariously with guile and charm by Tony Stratton-Smith (aka Strat) – supported Genesis wholeheartedly. “We never ever told them what to do,” Glen Colson says. “They had complete artistic licence, sleeves, anything they wanted to do. All we did was help them. They all looked alike. They were just very odd. I don’t think they had groupies. I don’t think they took an awful lot of drugs. Maybe a tickle here and there. They were very intelligent; fish out of water, really, in the rock business. They were these public school boys edging themselves into it.”

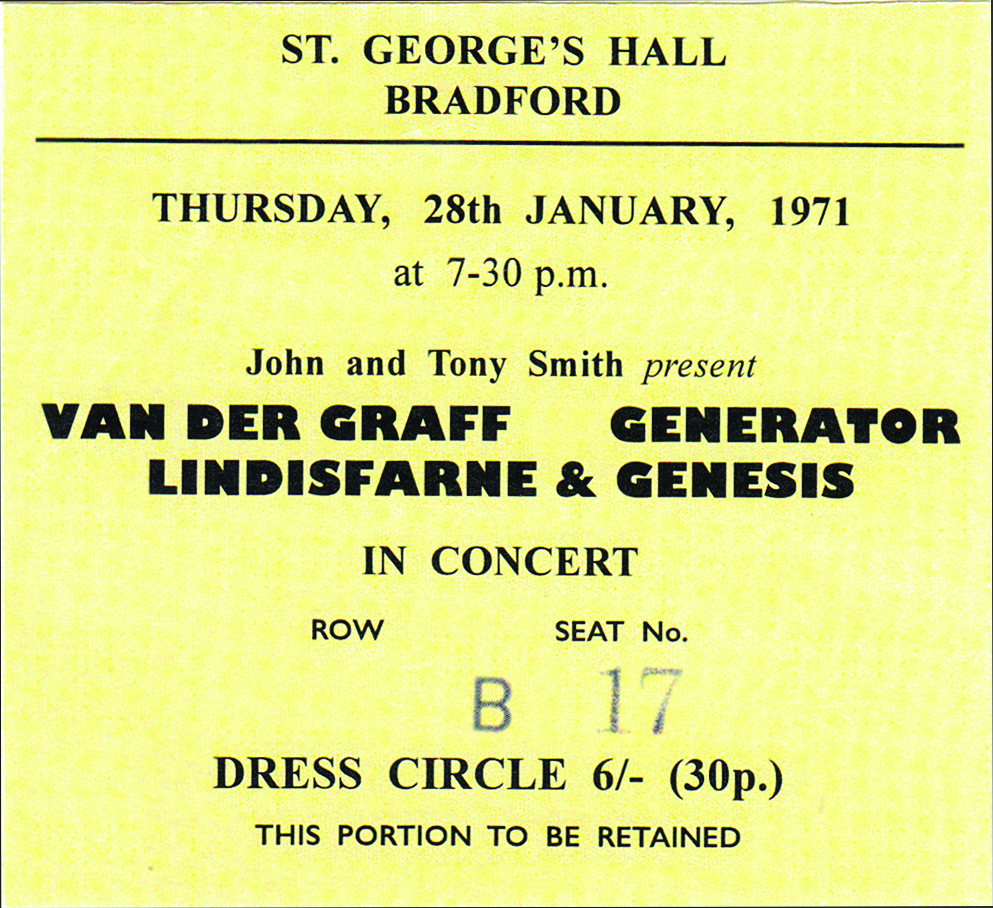

Their edging was positively heightened by the ‘Six Bob Tour’, one of Strat’s most wizard wheezes – three Charisma acts, Van der Graaf Generator, Lindisfarne and Genesis, playing up and down the country for 30 new English pennies. Decimalisation was introduced in the UK on February 15 – what better way to celebrate? There are pictures of Genesis at the Lyceum on the opening night of the tour, with Gabriel with his thankfully short-lived ‘underbeard’, the sort of vest commonly referred to as a beater, and Hackett in his velvet flares undermined by very sensible shoes, studiously fingering his new Gibson. The inexperienced performer remained rooted to the spot after the band had finished. “I think he expected them to say, ‘Well, it’s been great, guys. Thanks’,” Macphail laughs. “All the band left the stage and he was frozen in the headlights. I went up and said, ‘It’s okay, Steve, it’s over’, and led him off.”

“He literally took me, shell-shocked, by the arm. I’d rehearsed everything except leaving the stage,” Hackett says today. “I was very green. And literally, my face was green. I wouldn’t say boo to a goose: full of aspiration and low on expectations.” Although nervous, Hackett’s big idea was bringing a new instrument to the band – the Mellotron.

“It was very much Steve who wanted the band to sound like an orchestra,” Macphail says. “He was a huge King Crimson fan. He kept saying we must get one. Eventually, Tony agreed. We ended up buying a slightly fire-damaged one off King Crimson.”

“I’d seen it used live and, from a distance, there were moments when you could believe it was an orchestra,” Hackett continues. “The songs were operating outside of the frame of pure rock. Tony used it very well. It was a transformative gift.”

Genesis really honed their craft on the Six Bob Tour – offering middle ground between the rowdy roistering of Lindisfarne and the complex cloistering of Van der Graaf Generator. Mike Rutherford suggested that Genesis learned to structure a set from watching VdGG, doing the opposite of what they did by putting all the quiet and loud songs together in blocks. Hackett saw the mixed blessing of being the opening act: “We were the Christians thrown to the lions, to warm up the crowd.”

“Genesis were so incredibly rehearsed,” Glen Colson says. “They had a vision, down to the last lighting call, the last lick. Every night was like a record. Peter would say the same thing, tell those funny little stories. They’d go on at 7.30pm and they’d come off at 8.30pm. And it was exactly the same every night. They were like serious students of music; they weren’t like other rock’n’rollers.”

Banks was later to say, “People would complain, ‘You always play the same thing every night,’ and I’d say, ‘But don’t you understand that when people improvise, they tend to play the same things every night, but just in a different order.’”

There was little money and Macphail and Paul Davidson supported the group by driving the equipment and the band in a long-wheelbase Transit. “All the gear was from when they were living out in the wilds of Surrey,” Davidson recalls. “A lot of it was very old. Richard spent an enormous amount of time changing plugs, making sure things didn’t crack. He spent hours repairing stuff, so that they could get by at the next gig. There was bits of equipment that the band loved. Never mind the emotional attachment to it, it should have been decommissioned! Phil would get quite frustrated with the fact that things weren’t quite as they should be. If leads came unstuck or mics didn’t work properly, it was unprofessional and he was just a true pro. Trooper.”

In early March, Genesis travelled to Brussels – where Trespass had become successful – to record for Pop Shop on Belgian TV. “The sound was horrible,” Davidson says. “They painted the whole studio white. There was a mud and gravel pathway into it. It been raining. We had to drag all the gear onto a beautiful, pristine white studio floor. It went brown underneath all the equipment.”

A week later, Peter Gabriel, just turned 21, married Jill Moore at St James’ Chapel, London. It was during his wedding that the band learned that Trespass had climbed to No.1 in Belgium. There was no time for a honeymoon, the schedule allowed just a few days off.

Another key to the group’s later success was a show they played at Green’s Playhouse, Glasgow, that April on the second leg of the Six Bob Tour. The city was always to have an incredible affinity with Genesis: “It was the first time any of us had been in Glasgow.” Paul Davidson recalls. “None of us knew what to expect. As they played, it was quiet. Very quiet. There was no lobbing of cans or shouting. By the time of The Knife at the end, I wasn’t sure how it was going to go. Everyone went nuts, shouting and cheering: they absolutely loved it. It was one of the most remarkable gigs I’ve ever done.”

A lot of the writing for Nursery Cryme was done at Rod Mayall’s studio in Sherriff Road, West Hampstead, across the road from the Railway Hotel (aka jazz club Klooks Kleek). “Rod had the most incredible bands rehearsing in what was effectively a one-room flat,” Macphail recalls. “He would fold the bed up, move all the furniture out of the way.” Genesis would decamp there on days off the road.

“It was quite a small space,” Hackett remembers. “But compared to what

I’d been used to before, it was bloody amazing. It’s the first time I’d really played with a drummer working at that level. Phil came in with the force of a thunder god in the same room and I realised that my amp was not going to make it. So, straight away, I had to go through an equipment update.”

Macphail would set up and with the band safely ensconced, go on his travels: “I’d go down to Shaftesbury Avenue, and then Charlie Foote’s in Golden Square to get drumsticks and the broken tambourines. Peter was always hurling his microphone around; Shure, the microphone people, had a place the other side of Blackfriars Bridge; I’d go there first thing, drop the mics off, and then pick them up later. I’d go into Charisma, and get the wages from Fred Munt.” Macphail would return and often hear what they had been working on. “I distinctly remember the time they first played me The Musical Box. That is a very special memory.”

Although the song had been around in various forms for a while – its opening had been known as F# and was something Rutherford and Phillips had played

at Christmas Cottage on their uniquely tuned 12-strings – here it was, fleshed out, approaching the version that is known and loved. The group recorded the song on May 10 at the BBC for the Radio 1 show, Sounds Of The Seventies. It’s fascinating to hear how it was to develop over the coming months, and become one of the most decisive markers in the group’s long career.

Genesis came off the road in July 1971 and finessed Nursery Cryme at Luxford House, in Crowborough, East Sussex. This stately pile was rented to Tony Stratton-Smith by the daughter of its previous owner, Sir Hugh Beaver – the British engineer and wartime director general of the Ministry of Works, who came up with the idea for the Guinness Book Of Records.

Pereds, the company co-founded by rock’n’roll estate agent, Perry Press, discovered “properties for busy people in the entertainment industry”. He located Luxford and Strat was offered it for £25,000. “It’s now worth £1.5m!” Colson says. “We got it for 25 quid a week. Strat was after the Winwood/Traffic effect.”

The famous ‘getting it together in the country’ that Traffic had pioneered in 1967 was seen as a positively progressive way to write and rehearse. “I only realised much later that Strat rented that crazy house,” Macphail says. “The idea of Strat being this sort of country squire was a little bit of an exaggeration. It was a great place to hole up. There were some stables, which we set up for the rehearsals, and then I went back to my role as chief cook and bottle washer.”

“It was [allegedly] built from wood from the Spanish Armada,” Colson continues. “One evening, I was there listening to a Van der Graaf Generator test pressing. The guy from one of the paintings was in the room with us. As I turned around, he ran back into the painting. The guy in that painting died in that room.”

“It was an idyllic summer,” Steve Hackett says. “We had a place to work. One night, famously, we worked on The Fountain Of Salmacis, at midnight. I think it’s the only time we’d ever worked that late. We’d all had a nice dinner and were very relaxed. It all came together in a very symbiotic, charmed way.”

It was also the first real opportunity to incorporate the Mellotron, the new instrument that Hackett had campaigned for: “This beast came into our lives and I definitely remember it down at Luxford,” Macphail recalls. “What Tony did with it was incredible. Steve and Mike communicated through the guitar; I would see them off somewhere, out in the garden if it was a nice day, or in one of the rooms upstairs. They’d be there with their instruments. Steve slipped into Ant’s shoes musically with Mike pretty easily.”

It was at Luxford that Phil Collins saw the dynamics of the group close up, with the mood swings of the Charterhouse core. Collins quickly rose above it: “I’m in my element,” he wrote in Not Dead Yet, “revelling in the creative freedom, the free flow of ideas, the scale of ambition, the length of our songs. I feel emboldened and liberated, encouraged by the guys to contribute.”

“Phil was already a star, but he was very low key,” Hackett says. “The others had been at school together, so they knew each other very well. This was heady stuff for me. It was like joining a regiment, and I wasn’t sure which way to pass the port. We needed each other. And I think we all learned a lot from each other.”

Just over a year after they’d recorded Trespass there, Genesis returned on August 2 to Trident Studios in London’s Soho to make Nursery Cryme. John Anthony returned to produce with David Hentschel – who had assisted, uncredited, on Trespass – as engineer. Trident’s mark of quality had been established when The Beatles recorded Hey Jude there in 1968, and while Trident-associated producers/engineers such as Gus Dudgeon and Ken Scott were working with regulars there such as Elton John and David Bowie, John Anthony had cornered the prog end of Trident’s roster by working with Rare Bird, Van der Graaf Generator and indeed, Genesis. Such was the magic

in the air in that insignificant alleyway in Soho, that in August 1971, Bowie recorded Hunky Dory, Elton Madman Across The Water and Genesis Nursery Cryme. That’s Changes, Tiny Dancer and The Musical Box. All in the same studio in the same month.

“I was in Trident Studios all the time,” Glen Colson recalls. “Marianne Faithfull was living on the wall, taking heroin in St Anne’s Court. Francis Bacon used to pick her up and buy her a meal. People would piss there as well. Rats everywhere.”

“Trident was extremely colourful,” Hackett agrees. “Ladies of the night and the watering holes of Wardour Street – it was rather extraordinary. It seems as if the whole of the music business was really centred around one square mile around there.”

The band were disciplined, working quickly and professionally. They knew the material well. “I think John Anthony did a good job,” Hackett says. “He wanted to get the mix all in one go, though. If you were working on a 12-minute-long track, and we were 11 minutes in, and somebody forgot to switch something on, we’d have to go right back to the beginning again.”

Richard Macphail, who frankly had been the most consistent member of the group’s audience, felt Anthony “just didn’t capture the power of the band. I was used to listening to it live, whether it was in rehearsal room, or at gigs.”

Nursery Cryme revels in its world of ornate, arcane detail, quasi-classical stylings: country manors, beheadings, an intersex god; and for a band with an average age of just 21, there was lots of talk of old men and the hands of time. Through the lines: ‘All this time has passed me by’, ‘Waste no time’, ‘Years seem so few’, ‘You can’t last long’, ‘Still summer lingers on, though her pictures soon shatter’, there’s a pervading air of melancholy.

For most listeners, Nursery Cryme is all about three of its seven tracks – The Musical Box, The Return Of The Giant Hogweed and The Fountain Of Salmacis. These songs take up 26 minutes of the album’s 40-minute total. “In between these however, are several songs that don’t quite fit that pattern,” The Waiting Room founder Alan Hewitt says. “One in particular was to be prophetic of things to come much later on: For Absent Friends. It featured the first lead vocal from Phil and, with its subjective realism, an indicator of much that was to follow in the band’s subsequent story.” As listeners were to later realise, Collins was an accomplished vocalist as well. It’s fascinating that the album displays Collins’ vocals so fully quite so early on: his double tracking of Gabriel’s vocal on The Musical Box and Harold The Barrel, and his solo voice on For Absent Friends.

At less than two minutes, the slight-yet-beautiful For Absent Friends highlighted the Collins-Hackett writing partnership that was to reach its zenith on Blood On The Rooftops from Wind & Wuthering in 1976.

“I recorded For Absent Friends many years later with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Colin Blunstone [for 1996’s Genesis Revisited album],” Hackett says. “I wanted to give it the sumptuous dressing I thought it should have. It’s like a pencil sketch among the portraits. The two big portraits on Nursery Cryme are The Musical Box and The Fountain Of Salmacis. Seven Stones develops in that way, too.”

The touching and strangely under- appreciated Seven Stones is trademark Tony Banks, all swells, sweeps and pathos. An old man realises life is based on chance; it features a fabulous Gabriel vocal (just listen to his pronunciation of ‘peril’); Harold The Barrel is a jaunty interlude, an exercise in McCartney-esque whimsy. Monty Python and Gilbert & Sullivan meet in a scripted tale of a suicide. Only Banks’ plaintive piano chords at the end suggest that Harold does indeed jump from his ledge. Harlequin is another slumbering number that demonstrates just how strong an influence Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young then had across popular music; it was written by Rutherford, who later was highly critical of his work.

The exaggerated eight-minute tale of rampaging plants, The Return Of The Giant Hogweed allows Gabriel to return to his The Knife holler, almost proto-punk. Steve Hackett’s fretboard tapping takes full effect on the introduction where he and Banks play triplets mirroring each other on guitar and keyboards. “I was thrilled that it sounded the way that it did,” Hackett says. The song was to become a staunch live favourite.

But what striking portraits The Musical Box and The Fountain Of Salmacis truly are. Gabriel said The Musical Box was about a “controlled English landscape under which festered violence and sex”. The nutshell? One child – Cynthia Jane de Blaise William – beheads another child – Henry Hamilton Smythe minor – with a croquet mallet. Later, Cynthia finds a musical box where Henry’s spirit rapidly ages in front of her; Henry then attempts to enjoy the pleasures of the flesh with Cynthia, before nursey arrives and flings the box at Henry. It’s impossible to know just where to begin analysing that. At over 10 minutes, it establishes the group as the prog Who, with incredible attack, yet tender restraint when appropriate. It is a bravura performance from all: “Whereas one guitar solo would be more than sufficient for Genesis most of the time, there were three,” Hackett says. “One little quiet one, a more raucous one, and then a more energetic one at the end with three-part guitar harmony, which Brian May said influenced him.” Soon, Gabriel would be wearing his old man mask on stage, presenting the piece as a spectacle of sinister musical theatre.

The main theme of The Fountain Of Salmacis had originated in the track Provocation, which Genesis had recorded for the documentary Genesis Plays Jackson in January 1970. …Salmacis is the reason people like prog, and adore Genesis. Of course, one could like other hits of the year such as Maggie May and Get It On as well, but you can quite see why boys in the common room – who had as much chance of meeting Maggie May and ‘getting it on’ as Harold The Barrel had of leaving that window ledge alive – all could seek solace in the books they had read. As opening lines go, ‘From a dense forest of tall dark pinewood, Mount Ida rises like an island’ is no ‘You’re dirty and sweet, clad in black, don’t look back and I love you.’

It was on …Salmacis that Trident displayed its limitations: “We tried to record the Mellotron on The Fountain Of Salmacis via just direct inject,” Hackett says. “It didn’t have the power that it had in the rehearsal room when it was through a PA.” The band moved half-a-mile up the road to AIR Studios at Oxford Circus. “We miked up two Hiwatt stacks at either end of the room. We really cranked it up and AIR Studios was literally moving air at that point. The power of the crescendo was mighty. We knew that the Mellotron really had to sound the bee’s knees for that track to work.”

The Fountain of Salmacis was, according to Glen Colson, “Very English, by way of Greek mythology. Tony used the Mellotron very well on that album. Very, very beautiful lines.”

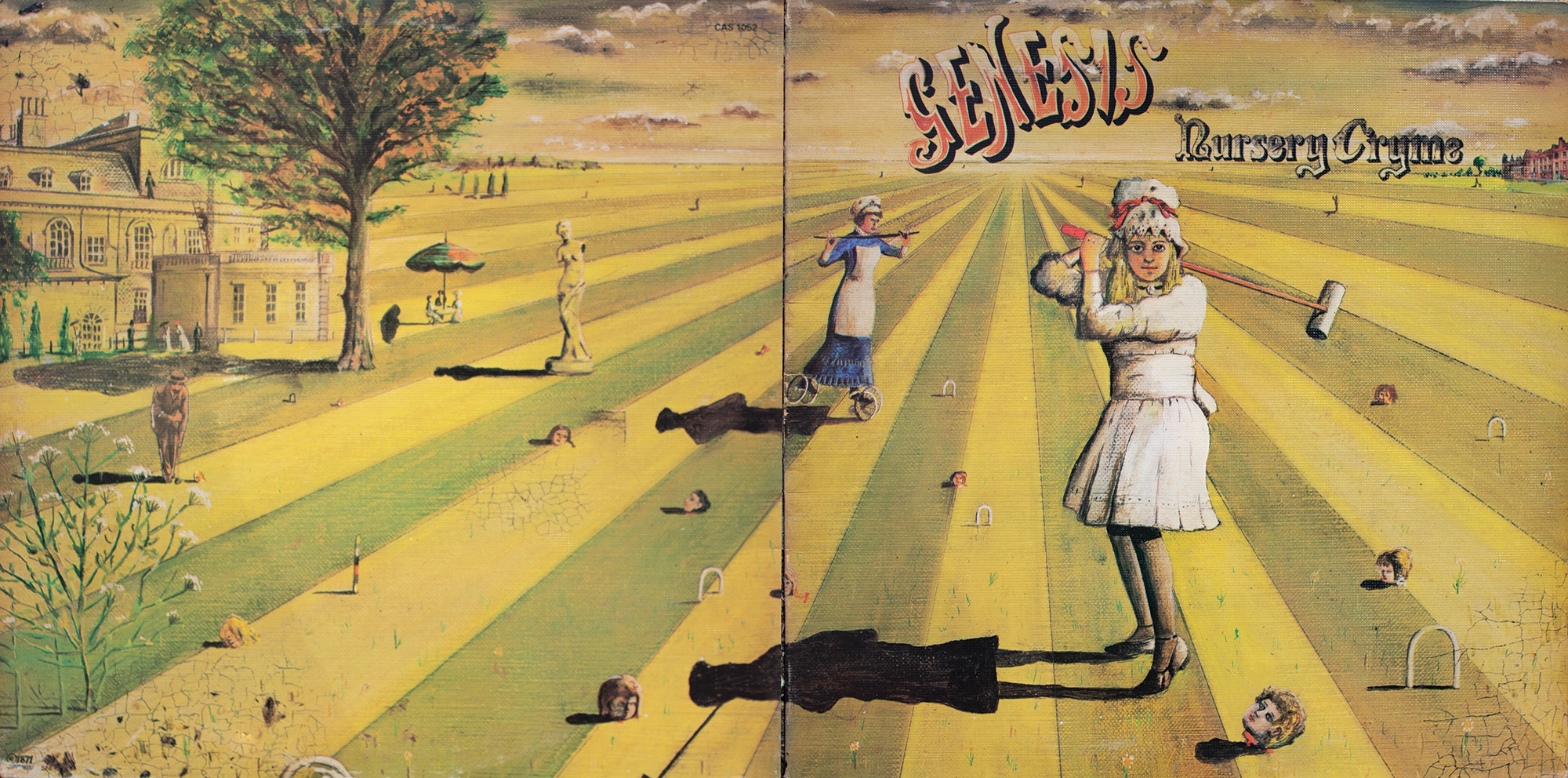

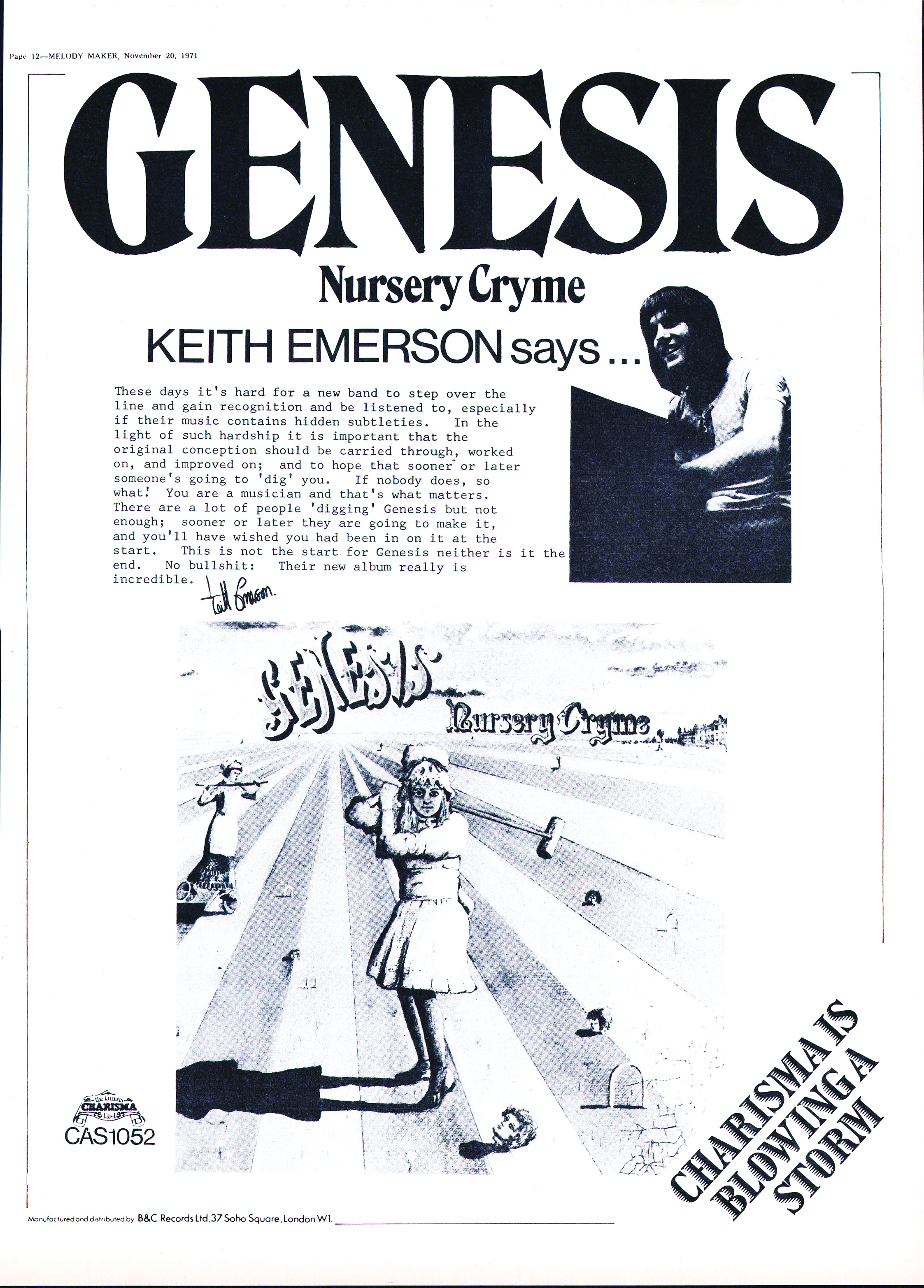

Paul Whitehead, who had designed the sleeve for Trespass, returned and drew one of his most iconic illustrations for Nursery Cryme. In its full whimsical Victorian glory (the copyright line says it all – 1871 – a happening 100 years earlier), we see Cynthia out there on an endless croquet lawn, mallet aloft, beheaded Henrys around her, as nursey wheels out from the distant mansion. “It seemed to do the trick,” Richard Macphail says. “Peter and Paul got well together and it was great that it captured the croquet. Good old Strat. These were all gatefold sleeves. Not two [pennies] to rub together, yet he would spare no expense.”

Nursery Cryme was released in the UK on November 12, 1971. Reviews were mixed, but largely positive. “A lot of people got it. And a lot of people didn’t,” Hackett says. “Should rock be going this way? Is it too removed from rock’s roots? Are there too many themes being taken from books rather than life? All valid criticisms, but you have to remember we were very young guys and fairly bookish.”

Led Zeppelin IV was released just before Nursery Cryme and Fragile by Yes soon after. Unlike those albums, which were instant successes by bands who had been in existence for roughly the same time as Genesis, the album was to sell about the same in the UK as Trespass.

The group returned to touring; there would be no more Six Bob Tours, they were on their own. They were back to playing The Red Lion in Leytonstone and the Lawns Centre in Cottingham. And that was after Nursery Cryme had come out. “Bands would suddenly appear; they would get enormous advances, like Roxy Music,” Macphail says. “There we were, slugging away for all these years, and bands would arrive with this most unbelievably amazing equipment, all spick and span. Curved Air was another one. We’re going, ‘Oh fuck, we haven’t even got flight cases.’”

As well as their popularity in Belgium, it was going to Italy in April 1972 and enjoying the success there that gave Genesis the strength to continue. “If the whole Italian thing hadn’t happened, it’s a question as to where it would have gone,” Macphail says. “Getting out there in April and August and getting such a reception was an enormously important thing for the band to give them the confidence to carry on, and then produce Foxtrot. Nursery Cryme is a milestone, however, because it’s the first album of the classic band. It’s tremendously important, especially with all the misgivings about whether they could go on or not without Ant. It seems bizarre now, but that was definitely around.”

Steve Hackett looks back on Nursery Cryme with enormous affection: “This was the first year I was doing professional gigs,” he concludes. “I got a Hiwatt stack, a Les Paul and the 12-string. It was guitar heaven for me. I probably talk about it in more glowing terms than the others, for whom it was just another year in the life of Genesis. For me, this was day one.”

Nursery Cryme may not have the unity of Foxtrot – which was to reach its pinnacle on Selling England By The Pound and was robust enough to be put under intense strain on The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway – but it is, without doubt, the blueprint, the turning of the corner, Genesis’ coming of age. You can hear it: it’s there in the piano break in The Return Of The Giant Hogweed, which hinted toward Firth Of Fifth; the elegiac candour of For Absent Friends presages the poignant populist ballads of the group’s later years; Harold The Barrel, the capers of Willow Farm, Epping Forest, Counting Out Time and Robbery, Assault And Battery; and without doubt, The Musical Box was the trailer for their undisputed career main feature, Supper’s Ready, less than a year into the future.

This article orginally appeared in issue 122 of Prog Magazine.

Daryl Easlea has contributed to Prog since its first edition, and has written cover features on Pink Floyd, Genesis, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel and Gentle Giant. After 20 years in music retail, when Daryl worked full-time at Record Collector, his broad tastes and knowledge led to him being deemed a ‘generalist.’ DJ, compere, and consultant to record companies, his books explore prog, populist African-American music and pop eccentrics. Currently writing Whatever Happened To Slade?, Daryl broadcasts Easlea Like A Sunday Morning on Ship Full Of Bombs, can be seen on Channel 5 talking about pop and hosts the M Means Music podcast.